Abstract

This paper presents a “virtual archive” of women’s epistolary exchange in

19th-century Finland. By harmonising metadata from over 1.2 million letters and over

100,000 correspondents across key cultural heritage organisations and leveraging

linked open data, we gain an unprecedented view of 19th-century epistolary

communication and 20th-century archival practices. Using quantitative analysis,

enriched metadata, and network visualisations, we explore the gendered nature of

these collections. Are women archival protagonists, or are their materials embedded

within the collections of male relatives? Do the data reveal overlooked women with

extensive archival networks absent from historical narratives? We introduce the

framework of “critical collection history,” which combines theoretical debates

and research interests from critical archival studies and digital history and

combines them with contemporary digital methods. This approach underscores the

necessity for scholars using data-driven methods in historical research to critically

engage with digitised archives. Moreover, critical collection history highlights how

“big cultural heritage metadata” can expose archival biases and enhance our

understanding of source limitations – biases that digital scholarship may

unintentionally perpetuate.

1 Introduction

A few years ago, we contacted the key cultural heritage organisations in Finland and

asked what we thought was a simple question touching on central historical source

material: “How many nineteenth-century letters do you have in your collections?”

The answer was simple, though not quite what we expected: “There is no way of

knowing.” This means that neither the organisations nor the humanities scholars

who regularly use these materials have a comprehensive view of the extent or basic

structural characteristics of these collections. Consequently, we cannot assess their

inherent biases or distortions, nor can we evaluate the representativeness of the

collections in relation to nineteenth-century “epistolary cultures”.

A reasonable follow-up question is why information about archived material is

important. After all, scholars have successfully used the contents of epistolary

collections to answer a wide variety of historical research questions since the

establishment of national and other archival institutions and the development of

historical methods based on primary sources. A lack of interest in the logics

or

“ethnographies” [

Dirks 2002] of complete archival collections is likely due to hermeneutic and microhistorical

research interests among scholars immersed in

historical epistolary exchange. It is also due to the difficulty of obtaining

accurate and comparable quantitative data on vast and diverse materials accumulated

over decades or even centuries and catalogued in astonishingly diverse ways. However,

when combined with the latest digital humanities technologies, collection-level

archival metadata offers untapped potential for historical enquiry.

In this paper, we suggest that the research agenda of digital historians should be

expanded to include questions about the composition of archival collections. We

analyse a new digital archive constructed by combining letter metadata (e.g.

information about senders, recipients, dates and quantities of letters) from

databases, finding aids and archival catalogues of person and family archives held

in

various Finnish cultural heritage organisations. This

“big

metadata” [

Enqvist and Pikkanen 2024] transcends organisational boundaries, enabling

us to obtain quantifiable and comparable information about the collections. When we

transform it into linked open data and connect it to external sources, such as

biographical and other datasets and ontologies, we can enrich the data with

categories not present in the archival metadata, such as the gender of letter writers

and recipients. This allows us to observe relations that are simply not detectable

in

traditional archives of printed finding aids or organisational archival

databases.

This paper argues that a fruitful intersection exists between digital humanities,

computational humanities, and critical archival studies, which we refer to as “critical collection history”. While it may be possible to

conduct such research using traditional methods, we aim to demonstrate that, at its

most effective and ambitious, critical collection history is digital collection

history. Repurposing information stored in archival finding aids and other

repositories of archival metadata using computational methods provides us with an

unprecedented and powerful tool with which to explore the interplay between

historical source criticism and the archival politics of inclusion and exclusion

(Whose materials are preserved by cultural heritage organisations and made available

for scholarly and other purposes?). This approach also allows us to gain new

perspectives on the interaction of historical actors within past contexts.

There is a well-established international scholarly tradition of compiling and

editing carefully curated collections of correspondence. In the last 15 years, such

data have been published as digital research resources and, in many cases, as linked

open data. Projects such as the EU-funded large-scale Reassembling the Republic of

Letters (RRL), the Circulation of Knowledge and Learned Practices in the

17th-century Dutch Republic (CKCC) and the German correspondence metadata aggregator

correspSearch, mainly focus on the epistolary materials of learned men, because

traditional epistolary editions have centred on this group.

Our material allows us to adopt a more comprehensive perspective. In what follows,

we

will address the gendered aspects of nineteenth-century epistolary collections in

Finland. We are particularly interested in the traces that nineteenth-century women

left in archival collections. The nineteenth century has been characterised as the

golden age of letter writing [

Lahtinen et al. 2011] and women have been

identified as the main protagonists of this development [

Monagle et al. 2023]. Does quantitative analysis of the collected

epistolary metadata confirm these qualitative findings? Based on our data, did women

play a prominent role in epistolary communication? Do they

“own” their

collections and archives? By delving into the collected metadata, can we find

individuals who are not part of our current scholarly canon? Throughout the paper,

we

will revisit a broader question: Does the material tell us more about

twentieth-century archival practices or particular developments in nineteenth-century

society?

Compared to previous publications of linked open data on epistolary metadata, there

are certain methodological and interpretative difficulties associated with the use

of

large collections of metadata gathered directly (“bottom-up”) from cultural

heritage organisations. The primary challenges pertain to the commensurability of

the

archival collections themselves and the validation of the results. There are no

comparable epistolary metadata datasets that we can use to measure the significance

and/or Finnish and nineteenth-century specificity of our findings. The best approach

is to use the entire dataset to provide context and calibration for its constituent

parts (i.e. different organisational or thematic collections), and vice versa.

2 Literature Review

The rapid expansion of big data and digital humanities since the early 2000s has

emphasised the importance of understanding the shape or contours of (digital)

archives and corpora. The research framework proposed in this paper is similar to

recent studies that have examined the

“anatomies” of

historical data collections and the processes involved in their creation, both before

and during digitisation (e.g. [

Tolonen et al. 2022], [

Beelen et al. 2023], [

Ortolja-Baird and Nyhan 2022]). It has

been suggested that large digital datasets require a new kind of critical attitude;

those who produce and use such data must pay particular attention to its local

context: how it was acquired and prepared, its strengths and weaknesses, and whether

it is fit for purpose [

Loukissas 2019, 8, 195], [

Ahnert et al. 2020, 54–55]. At the same time, it has been recognised

that much digitised historical material can be analysed using computational methods.

Indeed, quantitative analysis is particularly effective when we want to interrogate

the characteristics, structures, and properties of digital archives and collections

and reflect on the relationship between datasets and the phenomena they represent

or

model [

Hyvönen et al. 2021, 53], [

Guldi 2023, 29], [

Bode 2020, 4–5].

Over the past few decades, researchers in archival and cultural studies have been

addressing the same questions, albeit mostly in the context of analogue archives,

close-reading individual collections. Since the archival turn of the 1990s and early

2000s, there has been growing interest in analysing the processes involved in

creating, organising, appraising, and describing archival holdings, as well as the

ways in which these processes reproduce and/or challenge existing hierarchies,

dominant discourses, and ideologies ([

Edquist 2021, 109]; see

also [

Schwartz and Cook 2002], [

Taavetti 2016]; [

Ketelaar 2017]; [

Mikkola et al. 2019]. Critical archival

studies pay attention to the processes prior to the possibility of digitisation. Like

critical theory on a wider social scale, these studies are emancipatory in nature

[

Caswell et al. 2017, 2]. They seek to highlight injustices in

current archival research and practice, offering recommendations for improvement.

As

with researchers working with large digital corpora, the importance of analysing the

logics, classification systems and exclusions of archival collections has been

emphasised [

Dirks 2002]. Recently, digital techniques have emerged for

studying curatorial practices and the historical and cultural context of museum

curation and archival appraisal (e.g. [

Salway and Baker 2020]; [

van Lange et al. 2022], [

Enqvist and Pikkanen 2024]). Paradigmatic

quantitative studies of letter collections are the results of the aforementioned RRL

project (e.g. [

Hotson and Wallnig 2019]), as well as various case studies

that use network analysis (e.g. [

Ahnert and Ahnert 2019]).

3 Description of dataset

Our study uses information from letter catalogues and databases from the Grand Duchy

of Finland (1809–1917). However, as sets of correspondence often extend beyond the

designated end year of 1917, we have also included these data where available.

[1]

The dataset is available online

[2],

“upcycling” these collections for reuse as FAIR data for research, as suggested by [

Scheltjens 2023]. The current version of the dataset comprises around 1.2 million letters featuring

approximately 114,052 unique actors (senders and recipients) from nine organisations

and four digital editions (see Table 1).

[3].

Letter catalogues have also been used to create datasets in various other projects.

The information in these catalogues varies considerably (see [

Kudella 2019] for more on modelling in the RRL project, for example). In

our case, the archival metadata includes basic information about the senders and

recipients (whether individuals, groups, or families). While dates are often clearly

delineated in some well-curated collections, more often than not, they are given as

the span of a set of correspondence (e.g., 25 letters between 1870–1895). Beyond

archival organisations, we have knowledge of the archival collections in which the

letters are held. In Finnish cultural heritage organisations, personal materials,

including letters, are organised in separate

“collections”, or

“archives” as they are usually

called. In the Anglophone world, such collections are often referred to as

“papers” (for example,

“the Cecil

Papers”, referring to a collection gathered by William Cecil (1520–1598)

and his son, Robert Cecil (1563–1612)). However, to avoid conceptual confusion

between organisations and their collections, the term

“fonds” will be used when discussing a body of records created and

accumulated organically, reflecting the functions of its creator [

Fonds SAA Dictionary].

| Cultural Heritage Organisation |

Years covered (within 1809-1917) |

Letters and actors in the dataset |

| Åbo Akademi University Library |

1809–1917 |

366 614 / 27 299 |

| Albert Edelfelts brev (Albert Edelfelt’s Letters, SLS) |

1867–1901 |

1310 / 5774 |

| Elias Lönnrot Letters (SKS) |

1823–1887 |

6296 / 1117 |

| Finnish National Gallery |

1809–1917 |

11 092 / 2901 |

| Gallen-Kallela Museum |

1895–1914 |

144 / 4 |

| J. W. Snellman, kirjeet (J. W. Snellman Letters) |

1826–1881 |

1563 / 4733* |

| The Migration Institute of Finland |

1881–1917 |

359 / 35 |

| The National Archives of Finland |

1809–1917 |

292 073 / 32 372 |

| The National Library of Finland |

1809–1917 |

281 157 / 33 746 |

| Serlachius Museums |

1883–1899 |

411 / 136 |

| The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS) |

1862–1917 |

175 990 / 13 762 |

| The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) |

1809–1917 |

108 157 / 13 256 |

| Zacharius Topelius Skrifter (Zacharias Topelius Writings, SLS) |

1829–1898 |

1407 / 71 |

| Total |

|

1 246 573 / 114 052 (unique) |

Table 1.

Number of letters and actors (metadata) in the dataset extracted from the

letter catalogues of the cultural heritage organisations. Source: LetterSampo

Finland dataset (19 February 2025). The actors in different organisations are partly

overlapping.

*The number includes actors retrieved also from the letter content.

The metadata are transformed into linked open data by an automatic transformation

pipeline (see [

Drobac et al. 2023b] for a detailed description). The

resulting data model builds on international standards, such as CIDOC CRM ([

Doerr 2003]), Dublin Core and ICA Records in Contexts, to promote

interoperability with other datasets. The data model aims to facilitate the modelling

of relevant metadata properties collected from source datasets. The most central

classes in the current data model are

“Letter”,

“Actor”,

“Place”, and

“Time-Span”. Provenance (the MetadataRecord class) and

archival/collection-level information (Fonds and Organisation classes)

are also included.

To represent actors (senders and recipients of a letter) in different source

datasets, we use an adapted version of the proxy concept from the Open Archives

initiative Object Reuse and Exchange (OAI-ORE) specification. In our case, a proxy

signifies a particular viewpoint on a person or group within a designated source.

In

the harmonisation process, proxies that are identified (through

deduplication/disambiguation workflow [

Drobac et al. 2023a], matching

based on a trained probabilistic data linkage Splink model

[4])

to represent the same person or group are linked through a shared instance

of the class ProvidedActor. This class is an adaptation of the Europeana Data Model’s

(Doerr et al., 2010) class ProvidedCHO (Provided Cultural Heritage Object). In

Europeana, the ProvidedCHO

“represents the Cultural Heritage

Object that Europeana collects descriptions about”. In practice, a proxy

represents a

“local”, or source-specific, view of an actor

(with metadata ingested from that source), whereas a ProvidedActor represents a

“global” view of the actor by assembling all the

information about the actor from various sources. The core classes and properties

of

the data model are presented in Table 2.

| Property URI |

C |

Range |

Description |

| LETTER (:Letter) |

| skos:prefLabel |

1 |

xsd:string |

Preferable label |

| :was_authored_by |

1..n |

crm:E39_Actor |

Sender/creator of the letter |

| :was_addressed_to |

1..n |

crm:E39_Actor |

Recipient of the letter |

| :has_time-span |

0..n |

crm:E52_Time-Span |

Time of sending |

| :was_sent_from |

0..n |

crm:E53_Place |

Place of sending |

| :was_sent_to |

0..n |

crm:E53_Place |

Place of receiving |

| :type |

0..n |

:LetterType |

Type, e.g., letter, telegram |

| :fonds |

0..1 |

:Fonds |

Archival collection the letter is part of |

| :original_data_provider |

0..1 |

:Source |

The organisation that has provided the data |

| dct:source |

1 |

:Source |

Data source |

| :metadata |

1 |

:MetadataRecord |

Original metadata record |

| METADATA RECORD (:MetadataRecord) |

| :original_record |

1 |

xsd:string |

Datasheet row or document paragraph as in source data |

| :number_of_letters |

0..1 |

xsd:string |

Integer, can be interpreted (e.g. "[[1]]") |

| ACTOR PROXY (:crm:E39_Actor) |

| skos:prefLabel |

1 |

xsd:string |

Preferable label |

| :proxy_for |

1 |

:ProvidedActor |

The provided actor that connects different proxies |

| PROVIDED ACTOR (:ProvidedActor) |

| skos:prefLabel |

1 |

xsd:string |

Preferable label |

| :floruit |

0..1 |

crm:E52_Time-Span |

Time of Flourishing |

| PLACE (crm:E53_Place) |

| skos:broader |

0..n |

crm:E53_Place |

Place higher in hierarchy |

| wgs84:lat |

0..1 |

xsd:decimal |

Latitude of the coordinates |

| wgs84:long |

0..1 |

xsd:decimal |

Longitude of the geocoordinate |

| skos:prefLabel |

1 |

rdf:langString |

Preferable label |

| PERSON PROXY (crm:E21_Person) |

| rdfs:subClassOf |

crm:E39_Actor |

class-level property |

| :birthDate |

0..1 |

crm:E52_Time-Span |

Birth date |

| :deathDate |

0..1 |

crm:E52_Time-Span |

Death date |

| :was_born_in_location |

0..1 |

crm:E53_Place |

Birth location |

| :died_at_location |

0..1 |

crm:E53_Place |

Death location |

| bioc:has_gender |

0..1 |

bioc:Gender |

Gender |

| bioc:has_occupation |

0..n |

:Occupation |

Occupation |

| bioc:has_person_relation |

0..n |

bioc:Person_Relationship_Role |

Relation to other person (in role) |

| FONDS (:Fonds) |

| skos:prefLabel |

1 |

rdf:langString |

Preferable label |

| :original_data_provider |

1 |

:Source |

The organisation that has provided the data |

| :records_creator |

0..n |

crm:E39_Actor |

Records creator |

Table 2.

The core classes and properties of the LetterSampo Finland data model.

Column “C” means cardinality of the property.

4 Methodology

Our study is based on the availability of epistolary metadata as Linked Open Data

(LOD). Having transformed the metadata collected from various cultural heritage

organisations into a harmonised data model, we can analyse the resulting dataset as

a

whole, while taking into account the differences in archival practices between the

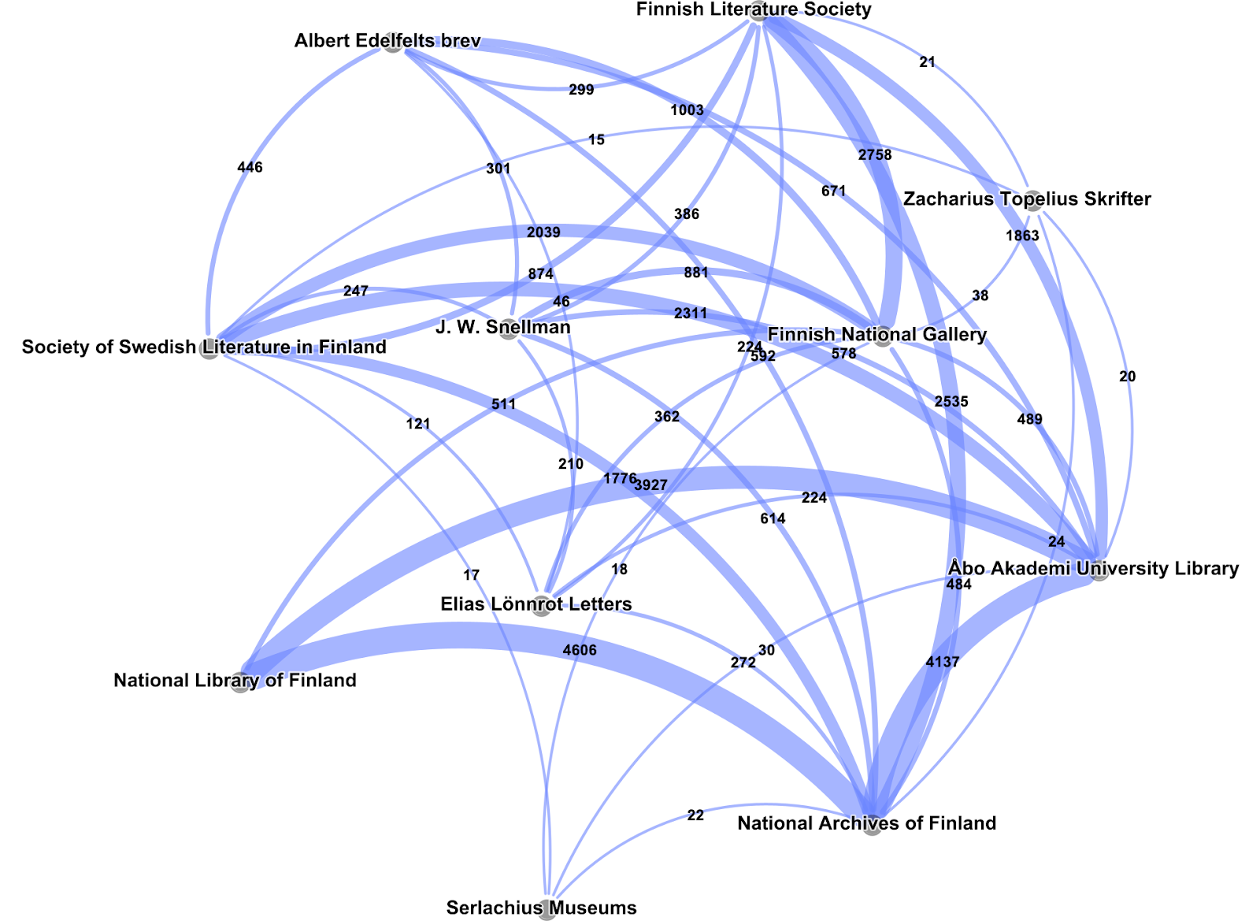

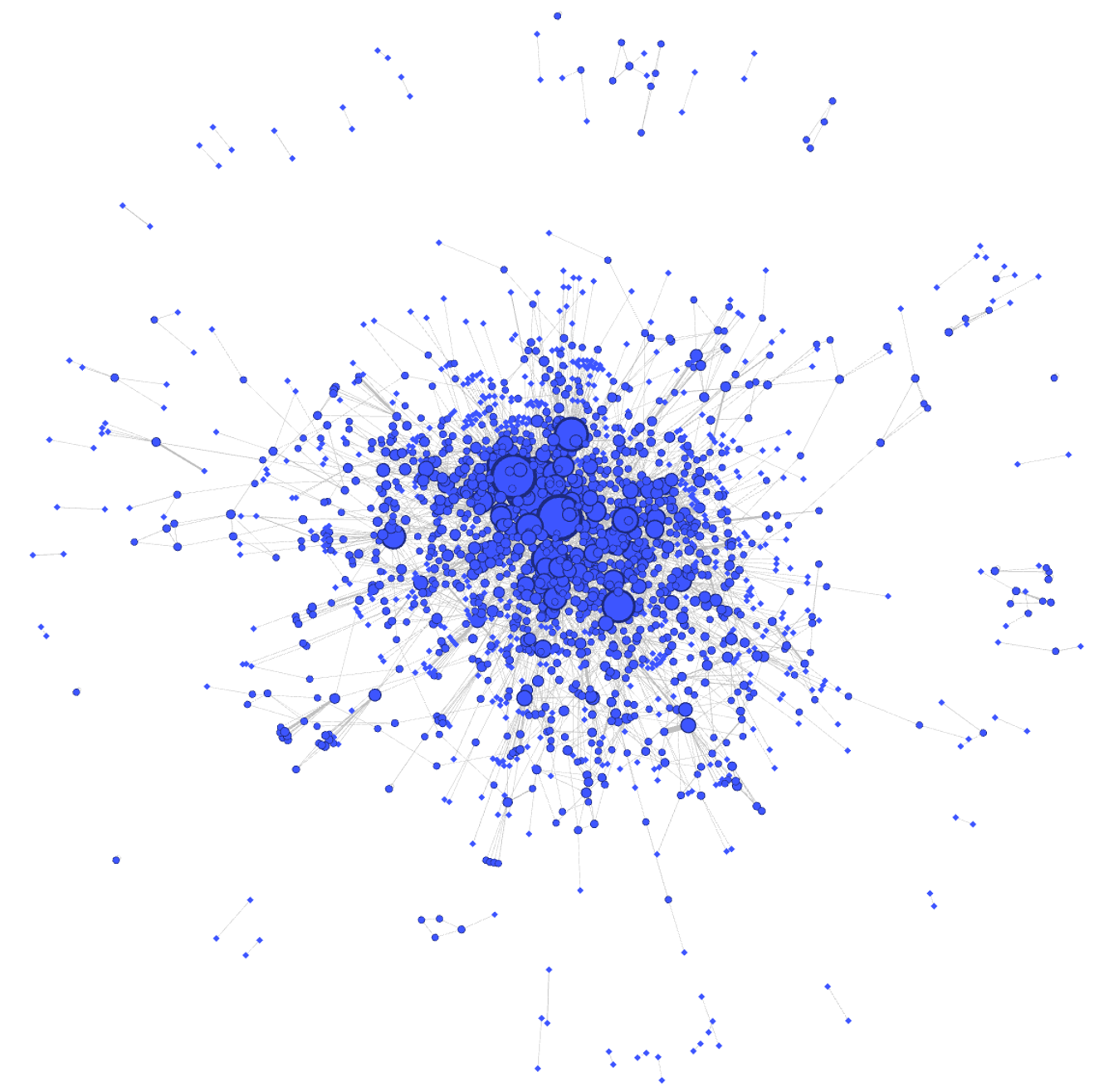

organisations that provided us with data. As illustrated in Figure 1, our research

can be extended from examining a single collection or the collections of a single

archival organisation to exploring the combined dataset (or union catalogue), thereby

capitalising on the inherent links between collections and organisations.

Figure 1 shows how many person-actors the different organisations have in common.

Making the data available in a machine-readable, structured format (RDF) and in a

SPARQL endpoint means that we have a multidimensional dataset that enables evolving

historical research questions and allows us to query the data in rich and meaningful

ways. Linking the data entities (e.g. person-actors) to external sources enriches

the

dataset with contextual information, providing ways to obtain details such as the

biographical background of the people in the dataset. At the same time, possible

links to external data sources, such as the National Biography of Finland or

Wikidata, indicate that the person in question is recognised as relevant, at least

from today’s perspective. The data for the studies reported in this paper were

generated by formulating SPARQL queries to select subsets of the dataset.

In addition to SPARQL queries, we use the LetterSampo Finland semantic portal

[5]. Based on the Sampo model [

Hyvönen 2022], the portal is implemented using the Sampo-UI programming

framework [

Ikkala et al. 2022]. It allows users to search, browse and

analyse letters, actors (people and organisations), archival organisations and

collections (fonds), and places in the dataset. The interface is based on the faceted

search paradigm [

Tunkelang 2009] and enables users to search for

letters from a specific time period, sent by a particular person and archived by a

particular organisation, for example. Visualisations include the yearly distribution

of letters, top correspondents, and correspondence networks. Data including

letter-sending locations can be visualised on a map.

Some cultural heritage organisations have built up their collections over decades

or

even centuries, during which time cataloguing practices, descriptive concepts and

standards have changed. In some cases, the material was initially handled by

non-specialists. Combined with the creative individualism of archivists, this has

resulted in a wide variety of finding aid formats, presenting one of the challenges

of data modelling work and transforming letter catalogues into machine-readable data.

The solution is to engage in continuous dialogue about humanistic knowledge interests

and the emerging data model. A linked open data solution has proven suitable for

modelling cultural heritage metadata relating to archives and historical figures.

However, perhaps even more important is the way in which the modelling process forces

us to consider the

“things” being modelled. What are the catalogued collections

of letters, and how can we conceptualise phenomena such as epistolary culture? As

[

Ciula et al. 2018, 345] write, models can be learnt from

“at two different stages, in the creation of the model and in its

application and successive manipulation”. In the case of epistolary

metadata, modelling the letter collections has led us to focus on specific aspects

of

the collections themselves.

In addition to the properties provided by the linked data, we use network analysis

to

construct specific correspondence networks. These networks illustrate changes in

women’s centrality over time, helping us to visualise the gendered structure of

nineteenth-century archival collections. Our focus is on contacts established through

correspondence rather than on the direction of interaction through letter-writing.

The main reason for this is the partiality of our collections (more on this below).

The intention behind these network visualisations is not to examine how the network

functions, but rather to offer an alternative viewpoint on the women in our

collection data through their interconnectedness. The layout used is a force-directed

model, meaning that the most important nodes in terms of connectivity remain at the

centre of the network. Although our primary focus is on the networks as collections,

we also highlight other themes relating to nineteenth-century women’s historical

correspondence as reflected in our dataset.

5 Case study

One way to challenge the boundaries of archival organisations and their collections

is to create a virtual collection of metadata relating to women’s letters. We will

proceed in three steps, firstly discussing the quantitative results in terms of the

total number of women actors and women as so-called records creators, then examining

the ten most active women in terms of letters, and finally exploring the position

of

women in specific correspondence networks over time. Our findings will be

contextualised in relation to archival practices, scholarly focus, and the

modernisation of nineteenth-century society. Finally, we will assess the

representativeness of our dataset as a whole. To this end, the Åbo Akademi University

Library and the Finnish Literature Society will serve as sample datasets and main

points of comparison. These organisations have exceptional collections covering

different geographical regions and representing the two national languages, Swedish

and Finnish.

The current dataset comprises 114,052 actors, 24.1% of whom are female. While this

figure is higher than that observed in previous European projects, it is less

pronounced than expected based on research emphasising that women’s epistolary

activity peaked in the nineteenth century [

Monagle et al. 2023]. However,

when we filter out groups and administrative units, and consider all person-actors

in

the dataset, the percentage of female actors rises to 29%. In the Åbo Akademi data,

the proportion of female actors is 31.7%, and in the Finnish Literature Society data,

it is 32.5%. Furthermore, of the 1,246,573 letters, on average 38% were sent by women

(alone or together with someone), and the corresponding percentage of letters

received was 36%.

In addition to examining the characteristics of the entire pool of person-actors,

collecting and enriching epistolary metadata gives us access to another class of

actors. In archival parlance, these are known as

“records

creators” or

“entities of origin”. These are

individuals, families, corporations or administrative units that

“create, receive or accumulate a body of records, personal papers or

objects”

[

Entity of Origin SAA Dictionary]. Their names are usually found in catalogue

headings and indexes of letter collections. Archival fonds contain letters received

by such entities, but often also letters sent by them. These may be copies kept by

the entity or originals added to the collection at a later date. Often, there are

also letters sent and received by other entities that may have had a family or other

connection with the original records creator. The Finnish Literature Society provides

a basic list of records creators on its website to serve as an entry point to its

epistolary material. In contrast, the Åbo Akademi University Library provides online

access both to its epistolary database and the database of records creators; however,

it remains difficult to find and combine information about actors who are not records

creators, even if they had extensive collections.

By comparing the total dataset of person-actors with that of records creators, we

can

see that the status of records creator is granted to a select few. Although the

number of actors varies greatly between our two sample organisations, only around

2%

of them are also records creators in both cases. In the case of the Åbo Akademi, we

can see that the gender of records creators is relatively close to that of the

overall actor data, but it is significantly higher in the Finnish Literature

Society’s collections (37.5% female). By contrast, the National Library of Finland

has a very ‘masculine’ catalogue of epistolary fonds: 85% of records creators are

men, with only 14.6% being women. These differences can be explained by the archival

policies and constituencies of these organisations. The Åbo Akademi University in

Turku was founded in 1919 to serve the Swedish-speaking minority in newly independent

Finland. Its collections include materials representing the old Swedish-speaking

aristocracy and intelligentsia — the country’s early political and cultural elite.

In

contrast, the Finnish Literature Society, founded in 1831, has a very different

profile. Its collections reflect the ideas of nineteenth-century Finnish-language

nationalists in the fields of folklore studies and Finnish language and literature.

The collections include the personal archives of literary writers, translators,

literary critics, and others. Through the National Library’s connection to the

University of Helsinki, professors, researchers, and other academics are well

represented in the library’s archival collections as professional groups.

Linking to external data sources provides additional insight into the actors and

records creators, as well as the general characteristics of the entire dataset. Only

19% of all actors can be enriched with information provided by links to databases

and

repositories of historical narratives that can be captured with digital methods.

However, these individuals are responsible for 85% of all letters. This means that

we

have a very prominent group of individuals who have left an extensive trace of

themselves in the form of letters and other personal papers, despite being few in

number, and a large number of individuals with few letters and connections. Such

“long tails” have been observed in other epistolary

collections of a different nature [

Ahnert and Ahnert 2019, 31]. When

it comes to the narrower group of records creators, however, about 80% of them can

be

linked to external resources, suggesting a continuing scholarly interest in them.

Collected lists of records creators can therefore serve as a kind of

“who’s who” of nineteenth-century Finland and nineteenth-century studies. The collections of

prominent records creators have also preserved the correspondence of individuals who

would otherwise have left little or no archival trace.

Thus, we can see that nineteenth-century epistolary collections in general, and the

group of records creators in particular, are dominated by literate elites and the

middle classes. This is consistent with what we know about the development of

literacy in this north-eastern corner of Europe. At the beginning of the nineteenth

century, writing skills were still rare, despite the fact that half of all Finns

could read. It was not until the introduction of primary schools in the 1860s that

literacy and text comprehension really began to spread. Statistics from the

Evangelical Lutheran Church indicate that, by 1880, 86.3% of the population could

read, though only 12.4% were literate. By 1900, the literacy rate had risen to 38.6%,

reaching 55.3% ten years later [

Latomaa and Nuolijärvi 2002]. The educated

elite and middle classes also appear to have taken care to preserve their

correspondence in personal, family and manor archives. These archives were

transferred to cultural heritage organisations when they began collecting private

archival material in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

These organisations operate under the principle of provenance (respect des fonds), which emphasises preserving records according to their

origin and within the units in which they were collected. However, a digital, virtual

metadata archive provides an opportunity to challenge established practices and offer

new perspectives on archival materials. For instance, we can explore the collections

of notable politicians and academics, or large family holdings, and ‘liberate’

mothers, sisters, and daughters by granting them independent status as virtual

records creators, thereby ensuring their immediate visibility and discoverability.

One such individual is Aline Reuter (née Procopé).

Table 3 presents the ten most active women in the entire dataset, ranked by the

number of letters. Interestingly, only half of these women are linked to content-rich

external resources; that is to say, they have a Wikipedia page or an entry in the

National Biography of Finland. For these women, we have readily available

occupational information. In contrast, much less information is at our disposal for

the other four women – the

“dark horses” of our virtual archive. Aline Reuter’s

correspondence at the Åbo Akademi comprises 8,178 letters (3,072 sent and 5,106

received). This makes it one of the largest collections of letters from a

nineteenth-century woman in our current dataset. You might think that such a large

collection, covering a period considered so formative for Finnish nationalism and

studied by generations of historians, would be used extensively. This does not seem

to be the case, however. The few mentions that shed light on her life can be found

in

the National Biography entries of her three famous professor sons and in the Reuter

family entry (see, for example, [

Autio 1997a] and [

Autio 1997b]). There are also Wikipedia pages (e.g.

“Edvin Titus

Feodor Reuter”) and a Geni.com profile (

“Aline Reuter”) which, for

technical reasons, cannot be used to enrich the data. These sources provide

information about her lifespan (1828–1916) and some details about her family (husband

and four sons).

| Name |

Total letters |

Occupations |

Archives |

Records creator |

External links (Wikipedia) |

| Procopé (Reuter), Aline (1828–1916) |

8178 |

- |

NAF, NLF, SKS, SLS,ÅA |

no |

3 (no) |

| Wrede, Hedvig Gustava Matilda (1854–1917) |

5582 |

- |

ÅA |

no |

2 (no) |

| Söderhjelm, Alma (1870–1949) |

5567 |

author, historian, full professor, docent, essayist, professor |

AEL, FNG, NAF, NLF, SKS, SLS, ÅA |

yes (ÅÂ) |

8 (yes) |

| Aalberg, Ida (1857–1915) |

5485 |

actor, stage actor, theatrical director |

AEL, FNG, NAF, NLF, SKS, ÅA |

yes (NLF) |

7 (yes) |

| Talvio, Maila (1871–1951) |

5396 |

writer, honorary doctorate, translator |

NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SKS) |

7 (yes) |

| Ackté, Aino (1876–1944) |

5242 |

opera singer, librettist |

AEL, FNG, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (FNL) |

9 (yes) |

| Granfelt (Lavonius), Magdalena Lovisa (1877–1946) |

5183 |

teacher |

ÅA |

no |

4 (no) |

| Gripenberg, Aleksandra (1857–1913) |

5078 |

member of parliament, writer, chairperson, politician, editor, public

figure |

NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SKS) |

7 (yes) |

| Haahti, Hilja Theodolinda (1874–1966) |

5004 |

author, translator, writer |

NAF, NLF, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SKS) |

7 (yes) |

| Reuter, Anna Hildur Elisabeth (1855–1936) |

4944 |

- |

NAF, NLF, SKS, ÅA |

no |

1 (no) |

Table 3.

Ten most active female authors in the dataset.

Source: LetterSampo Finland dataset (19 February 2025).

Note: AEL (Albert Edelfelt’s Letters), FNG (The Finnish National

Gallery), SKS (The Finnish Literature Society), NAF (The National Archives of

Finland), NLF (The National Library of Finland), SLS (The Society of Swedish

Literature in Finland), ÅA (The Åbo Akademi University Library).

However, obituaries of Aline Reuter in the newspapers provide further insights into

her life. She had 13 children in total, many of whom died young. She homeschooled

the

surviving children until they reached grammar school age, and she acquired such

excellent skills in subjects such as Latin and mathematics that, when her son Odo

Reuter, a professor of zoology, became blind, Aline Reuter (now in her 80s) took over

his professional correspondence and proofread his papers. However, more than her

obvious intellectual agility, the obituaries emphasise her

“rich

inner life” and remind readers that

“there were no

great events in her life” (see, for example, [

Dagens Press 1916]). This statement alone arouses curiosity about the

contents of Reuter’s extensive collection of letters, tempting one to immerse oneself

in her

“epistolary space”

[

How 2003] and reflect on its representativeness, for example with

regard to the experienced, personal nationalism of nineteenth-century women [

Eiranen 2021] or other significant ways of discursively shaping oneself

and one’s surroundings [

Monagle et al. 2023, 12].

“Mother Aline” is thus a prime example of a marginalised

or forgotten person who only becomes clearly visible when we recontextualise her

letters in the collected and enriched metadata. Indeed, it is only through the

combined metadata that we can confirm the extraordinary quantity of surviving

correspondence. By way of comparison, the most extensive set of male correspondence

is that of Senator Leopold (Leo) Mechelin (1839–1914), whose entire collection of

letters from various organisations totals 14,399.

We can make further observations about the gender distribution in the Finnish

nineteenth-century data with the help of network analysis and simple degree metrics,

which build on the above analysis of the number of contacts each person had. This

enables us to visually assess the extent to which the women in our letter collections

were connected. As our dataset spans over a hundred years, we decided to examine two

periods in more detail: 1830–1860 and 1880–1910, which reflect the socio-economic,

legal and social changes that affected women’s correspondence in the modernising

Grand Duchy of Finland. From the 1860s onwards, women gradually gained access to

higher education. As the country’s economy liberalised, women’s legal and economic

rights were strengthened, and they participated in associations and societal

movements. Hypothetically, this meant that women’s epistolary networks became more

similar to those of men, and we were interested to see if we could find traces of

this in the archived epistolary material.

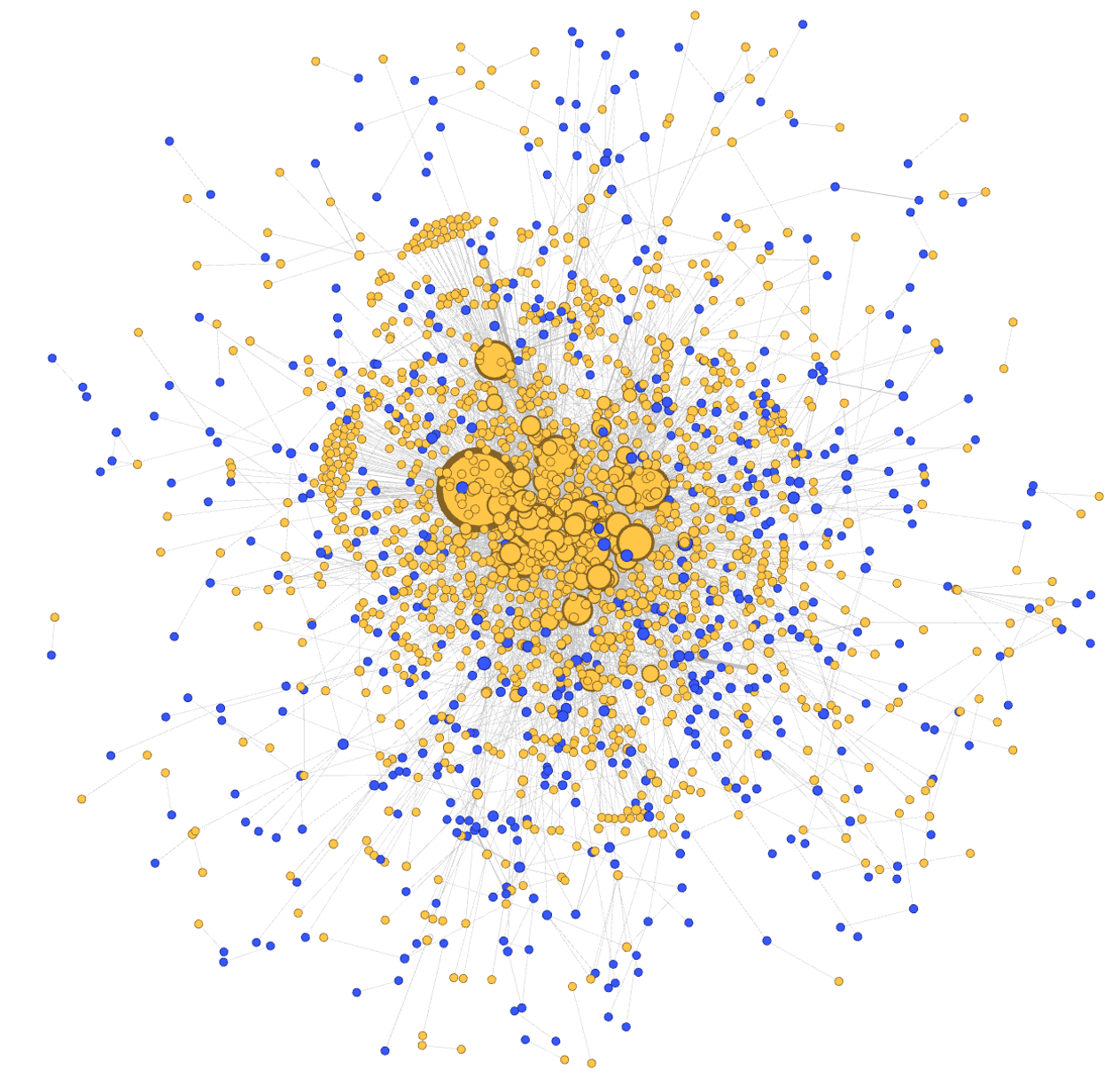

As expected, looking at the position of women in the correspondence networks reveals

that their connectivity increases as we move from the first to the second period.

At

the same time, the

“archival status” of the most

well-connected women and their links to external biographical databases undergoes

a

significant change. As illustrated in Figure 2, during the initial period of letter

correspondence (1830–1860), men dominate the centre of the network, with most women

(represented by blue nodes) situated in the middle and outer spheres. The ten most

connected women are also not central figures from an archival perspective (see

Appendix 2, Table 5). As they are not records creators, the bulk of their letters

have been archived as part of their families’, husbands’ or sons’ fonds. Furthermore,

linking to external databases has only resulted in links to genealogical databases.

Professional information was only found for two women (Fredrika Runeberg and

Elisabeth Blomqvist), who have also attracted academic interest (e.g. [

Klinge 2006]

[

Konttinen 2000]). The situation is quite different for the ten most

connected men of this period (see Appendix 2, Table 4): they are all records

creators; their letters originate from 7–9 archival organisations; and they are well

linked to external sources, including Wikipedia.

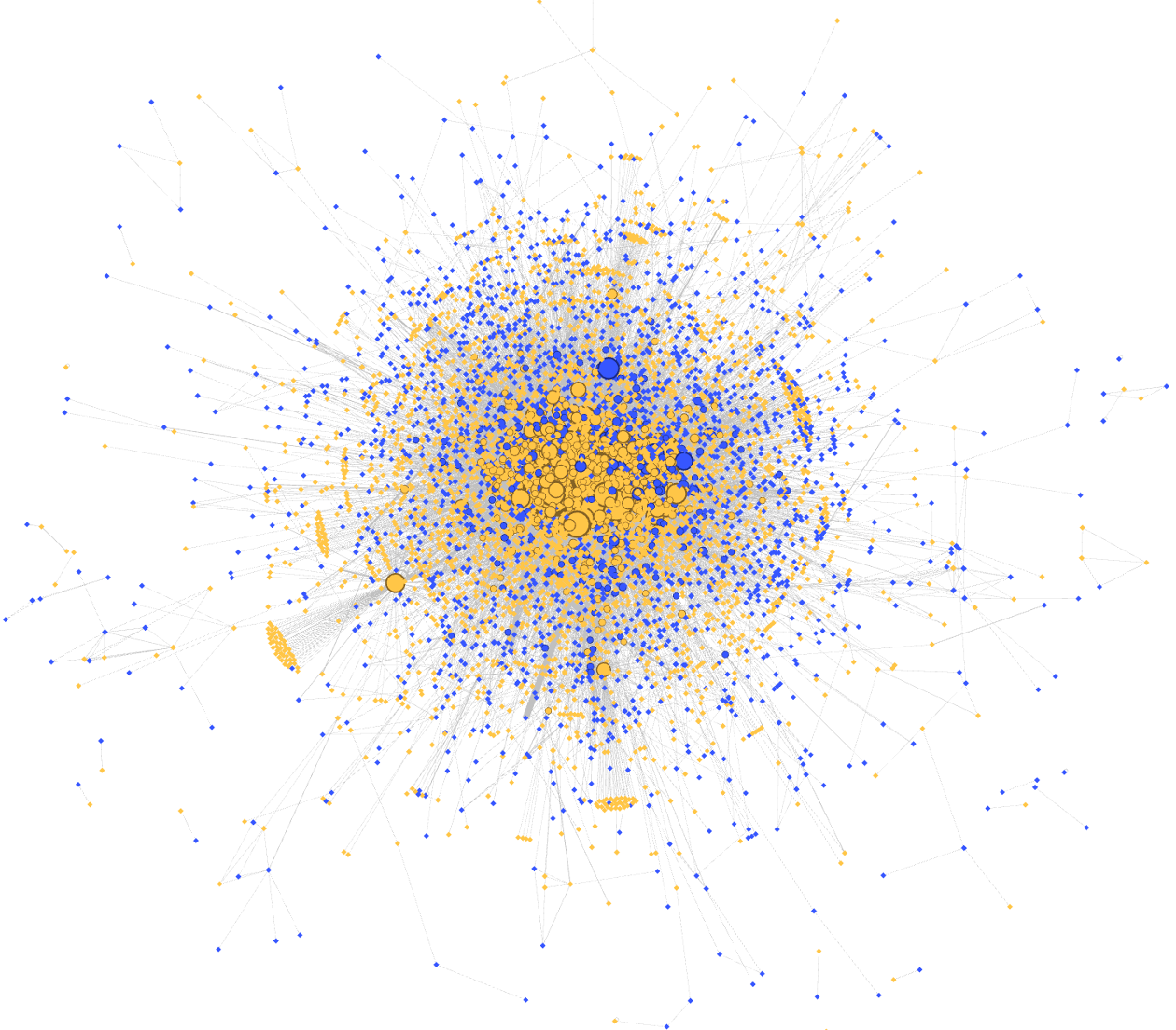

During the second period (1880–1910), women were more centrally positioned within

the

network, as illustrated in Figure 3. The profile of the women with the most

connections in this later period is very different to that in the earlier period:

nine out of ten of these women are records creators, and their letters are widely

distributed across different archival organisations (see Appendix 2, Table 7). These

women are well-known cultural figures – artists, writers and politicians – and are

well connected to external data sources. They also have a Wikipedia entry. Their

network profiles thus differ significantly from those of lesser-known figures such

as

“Mother Aline”, who, despite her extensive

correspondence, plays a more peripheral role in the network. In both periods, the

biggest difference in our metadata between men and women is that women have

significantly fewer contacts, even those who worked in the public and private sectors

in the late nineteenth century (such as the social activist and politician Aleksandra

Gripenberg; see Table 3 and Appendix 2, Table 7 and Appendix 3, Table 9). Based on

archival materials, women’s epistolary networks were narrower. However, as noted

above, the ties were proportionally stronger in terms of the number of letters

exchanged.

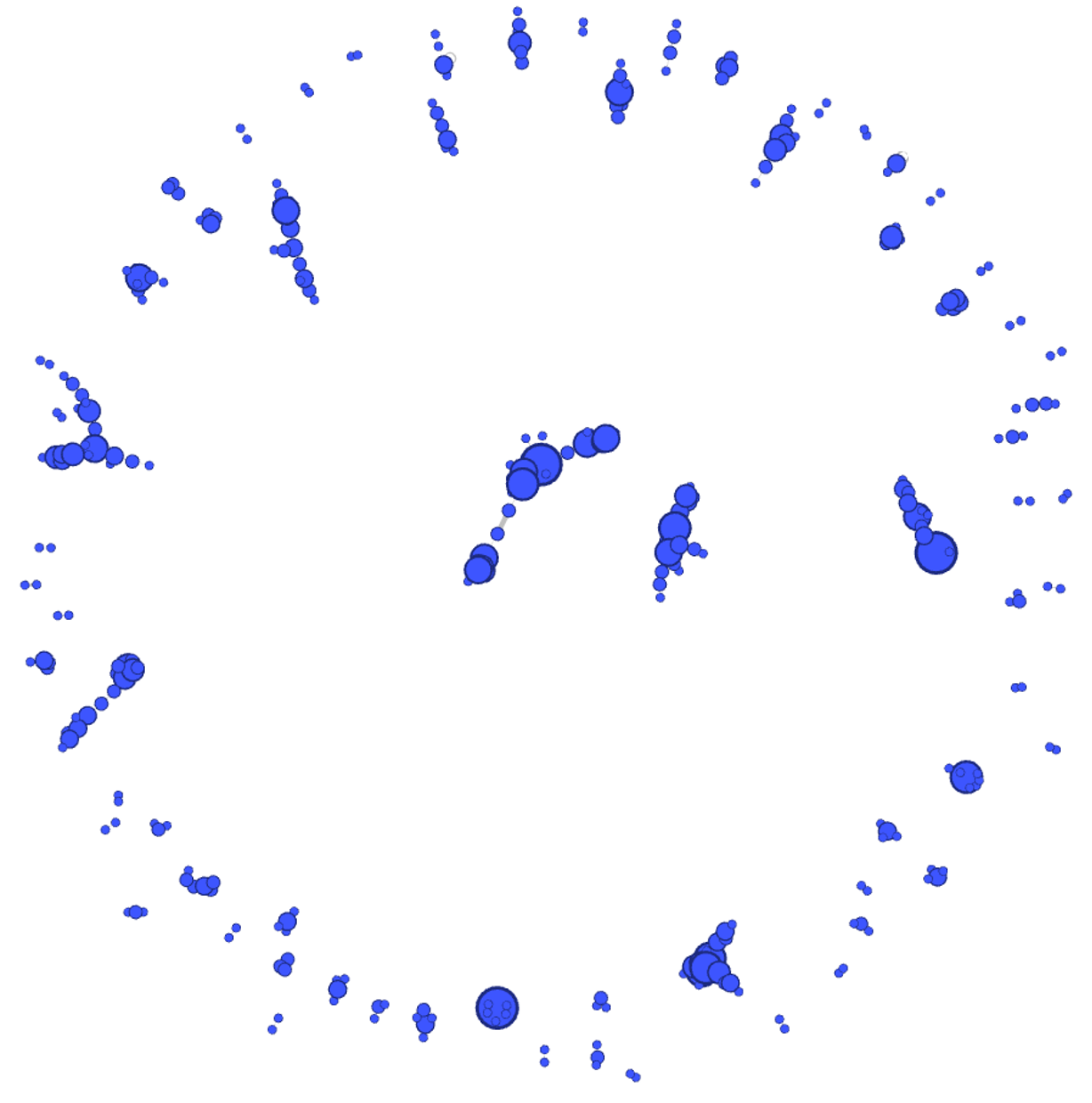

In addition, networks consisting exclusively of correspondence between women provide

further insight into the organisation of archival collections, the focus of scholarly

interest and the changes brought about by the modernisation of the country. The

configurations of women’s correspondence networks are illustrated in Figure 4 for

the

periods 1830–1860 and 1880–1910. During the earlier period, women exchanged

significantly less correspondence, and their networks formed several distinct but

small clusters. While most of the women are the same as in the full network, the

shape of the network now suggests a predominance of family networks, as previous

research [

Monagle et al. 2023] has suggested. However, further data

analysis and qualitative research are needed to confirm this. Additionally, many of

the women’s letters are uniquely archived at Åbo Akademi, likely due to the

institution’s substantial collection of family archives from the Swedish-speaking

population. For the second period (1880–1910), the situation is very different, as

can be seen from the shape and size of the network in Figure 4. The women were highly

interconnected, with significant nodes at the centre of the network. Examining the

most central women reveals that, with the exception of two individuals, all of those

in the

“women's network” and the broader network remain

the same during this period, albeit with slightly different rankings (see Appendix

3). Therefore, in the latter period, it is not possible to identify separate clusters

of women’s correspondence. Instead, women’s correspondence is interwoven with the

networks of the country’s artistic and cultural elite, whose correspondence is spread

across all the archival organisations in our dataset.

Despite these extensive collections, archived materials only provide patchy and

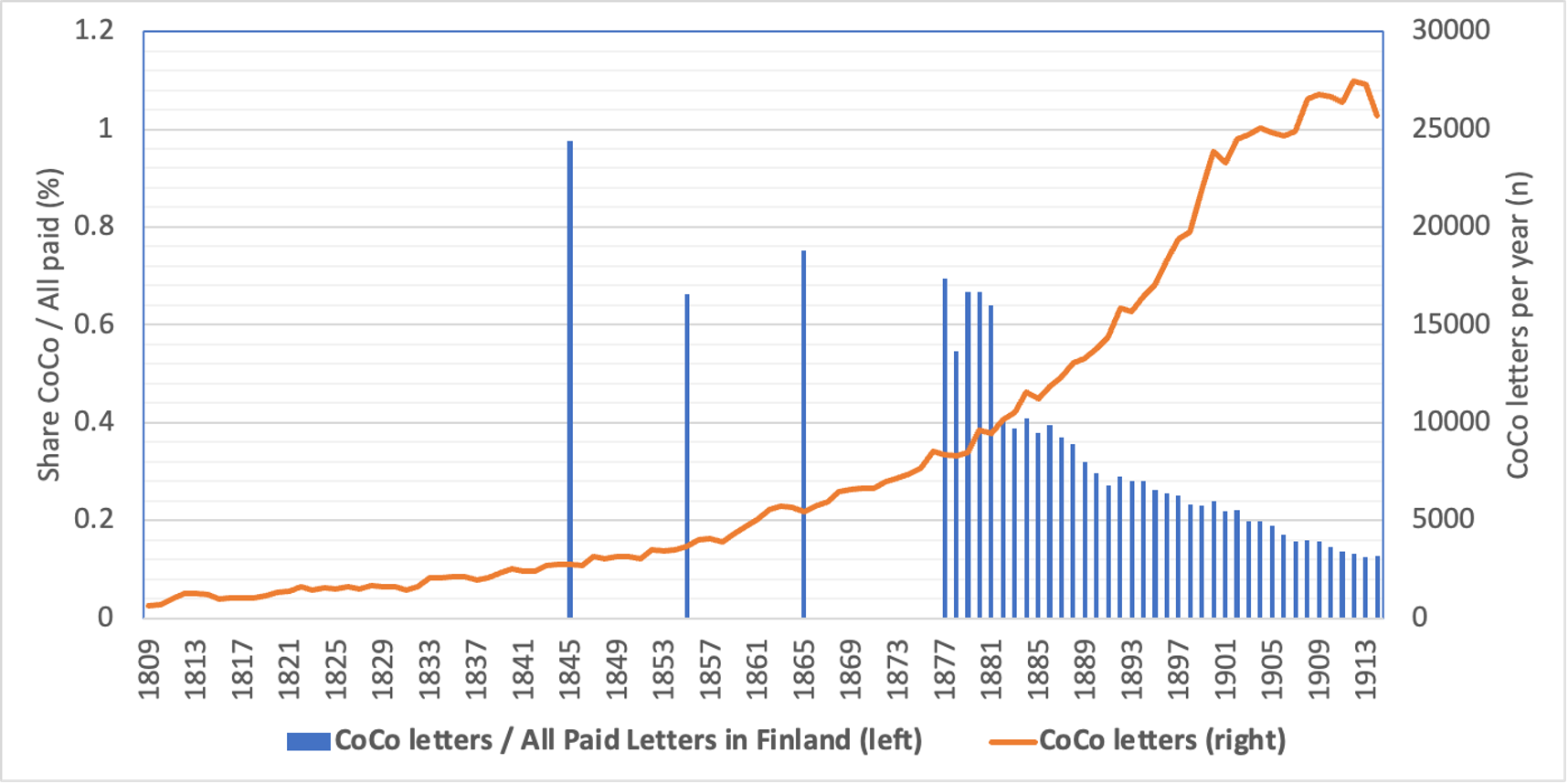

partial access to nineteenth-century epistolary communication. When we compare the

dataset — and thus the collections of the largest Finnish cultural heritage

organisations — with statistics on all letters sent in the Grand Duchy of Finland,

it

is clear that coverage and representativeness are low (Figure 5). The collected

metadata does not reflect the growth in letter correspondence in the country, which

was driven by the expansion of trade, commerce and administration, as well as the

development of technologies that supported easy and affordable letter exchange, such

as cheap postage and stationery, prepayment of letters and increasing delivery speeds

(Pietiäinen, 1988). After the mid-1880s, when literacy rates began to rise, archival

coverage decreased further still. It appears that archival organisations lacked the

means or interest to preserve everyday correspondence in the Grand Duchy, and

lower-class individuals and small businesses may not have had the inclination to

create personal archives. Therefore, an interesting question is whether we can

estimate what materials are missing. Can we see what is not there?

At the start of the data collection, we asked cultural heritage organisations to

estimate the proportion of their collections that were unorganised and uncatalogued

(see Appendix 1). The results of this survey clearly demonstrate a growing shortage

of resources for the labour-intensive work of archival description. However, it is

reasonable to assume that letters added to collections since the nineteenth century,

perhaps up to the 1980s, were more thoroughly indexed due to the greater availability

of human resources relative to the size of the collections. Nevertheless, the

collections do not represent a random sample of nineteenth-century epistolary

culture, as evidenced by the social and cultural status of most of the records

creators. Therefore, while cultural heritage organisations’ collections are not

representative of the majority of letters sent, especially in the late nineteenth

century, they do reflect the membership of the elite and upper middle classes

relatively well.

However, what has been preserved of the total body of correspondence that once

existed is often coincidental, even among the literate elite. For instance, Senator

Mechelin received 12,129 letters, which are kept in his family’s collection at the

National Archives. However, we only have 2,270 of his letters (mainly in the

collections of other individuals in five different organisations). Assuming that

people mostly replied to the letters they received, this kind of disparity in the

material points to definite gaps in the collections. Conversely, it is more

challenging to determine whether the proportion of female actors (24% of the total,

and 29% of those for whom gender can be identified) and the proportion of letters

sent and received by them (38% and 36%, respectively) is indicative of missing

material. Similar, large-scale datasets of epistolary metadata from other European

countries are lacking, making it difficult to compare our findings and results. The

closest we have are the results of the ambitious RRL projects mentioned above, which

provide a rare insight into the gender distribution of epistolary material from

earlier centuries. The datasets currently available in Germany and the Netherlands

show an overwhelmingly male correspondence of 85%, but this is understandable given

the projects’ premises.

6 Discussion

In the era of flourishing research on LGBTQIA+ histories, exploring the role of women

as archival protagonists may not seem very revolutionary. In fact, the first attempt

to enable sustained research on women’s history in Finland was made in the mid-1990s

with the publication of

Naisia, asiakirjoja, arkistoja: Suomen

naishistorian arkistolähteitä (

Women, Documents, Archives:

Sources for Women’s History in Finland, [

Härkönen 1994]), which

identified various archival collections of potential interest to the emerging field

of gender history. However, as we have demonstrated, applying data science methods

can render the process of critically revising archival collections much more

systematic and powerful. Epistolary metadata is, of course, only one type of

information that can be used to interrogate the role and visibility of different

social, cultural, or ethnic communities in our social narratives. Indeed, cultural

heritage metadata may offer a more affordable and realistic way of making dispersed

archival and museum collections accessible and researchable than mass digitisation

projects. However, metadata alone can be frustrating for scholars accustomed to

interrogating vast textual archives, and a dialogue between digital and more

traditional research methods is required. Nevertheless, using

“pure” metadata enables us to

“map missing bricks in

the wall of knowledge”, for instance by categorising individuals and social

groups whose biographies do not yet exist [

Guldi 2024, 525] – a

task we have begun with the help of Aline Reuter, among others.

Jo Guldi has recently referred to such digital approaches as

“counting the silences”

[

Guldi 2024, 524].

“Silence” is a

buzzword used by scholars to refer to missing data or issues that archives cannot

or

will not ‘talk about’. It is often used interchangeably with terms such as ‘gaps’,

‘bias’ and ‘occlusion’ (see also [

Carter 2006, 217]. To clarify,

[

Guldi 2023, 30–37] distinguishes between occlusion and bias.

For Guldi, a digital humanist who works with large textual corpora, the Occluded

Archive is an archive that is closed to view. It consists of materials that we cannot

access for various reasons. Occlusion operates at the level of political and

historical factors, as well as archival organisation (e.g. which social groups are

literate, which archives are preserved, and how relevant documents are hidden in

separate datasets). For Guldi, bias is

“dirt” or

“filth” in the textual content. This powerful metaphor refers

to racist, misogynistic and other expressions and narratives that carry a heavy

ideological burden. Historians are usually aware of such omissions and biases, which

they identify as part of their work. However, these factors are not always considered

when data science methods are applied to materials.

Our data consist of metadata from the letter collections; we do not have the content

of the letters in our dataset. This means that we need to introduce an additional

feature of occlusion: the partly accidental and partly selective nature of the entire

life cycle of historical and archived materials. Many archival theorists interpret

“silences” as tangible gaps in the archival record.

These gaps can arise from everyday practices such as the accidental disappearance

or

deliberate destruction of materials prior to and after archiving, or from appraisal

and subsequent rejection in a cultural heritage organisation ([

Fowler 2017]; [

Edquist 2021]). The historical reasons for

this kind of fundamental, irreversible non-preservation vary, and there is little

evidence of such processes producing structural bias in historical sources. However,

it may be possible to model some gaps using digital methods or conduct the

time-consuming task of searching organisational records for traces of decision-making

processes. In this paper, we have identified both gaps (in the representativeness

of

the data, compared with the information available on nineteenth-century postal

activity and literacy) and silences (in the lack of research on certain notable women

in our dataset) by examining what has been preserved in the collections of Finnish

cultural heritage organisations. A persistent

“silence” is

often only recognised in retrospect, for example, when a paradigmatic change in

theory or technology allows a new view of the archived material.

It is true that material separated into different repositories or organisations

is

a strong occluding factor. However, occlusion also occurs within individual

organisations. A key factor here is how organisations prioritise the creation of

metadata and categorise catalogued documents as open and accessible or closed (e.g.

[

Sherratt 2015]). Only collections that have been organised and

described can be made available to researchers and other users (see Appendix 1).

Furthermore, it has been argued that creating a fonds and assigning a records creator

carries significant intellectual and hegemonic weight, yet these decisions often

remain invisible [

Drucker 2021, 326], [

Friedrich 2021, 312–317].

Digital humanities scholars often work with materials that were originally indexed

in

a library context. While these bibliographic databases, catalogues, and digitised

repositories are incomplete and less representative than many scholars might hope

(see, for example, [

Bode 2020]), they do comprise fairly homogeneous

sets of materials. Furthermore, issues of archival access and its political

constraints are frequently examined in the context of sensitive government records

(e.g. [

Risam 2019]; [

Sherratt 2015]). However, it is also

important to recognise these mechanisms in relation to cultural heritage materials

and those held in private archival organisations. All organisations whose letter

metadata are included in our dataset have their own acquisition policies, enabling

them to accept or reject archival material offered to them, provided they justify

their decisions. Compared to material generated in library contexts and governmental

organisation records, archival organisations’ vast collections, particularly person

and family collections, seem more

“wild”, especially when considering material beyond

the high research canon. Cataloguing categories vary, information comes in different

formats, and many collections are only partially organised, with huge backlogs of

unorganised material.

7 Conclusion

In this paper, we introduce the framework of Critical Collection History. Using the

powerful qualities of Linked Open Data, this framework finds relevant features in

a

dataset comprising over a million letters and over 100,000 actors. It is motivated

by

discussions in the fields of critical archival studies and digital humanities. We

argue that critical collection history occurs when the boundaries of cultural

heritage organisations and their collections are erased and the structure of

traditional paper archives is challenged and

“weirded”. At the most general

level, critical collection history asks whose actions and experiences are important

enough to be archived and catalogued, and which individuals and groups are visible

in

finding aids, indexes and external research repositories. Digital technologies enable

us to examine archival collections individually and collectively as large sets of

historical data, not as static and inherently objective entities providing direct

access to the past, but as multi-layered, dynamic and processual entities resulting

from various historical, socio-economic and political processes. Similar to many

contextualising approaches to digital collections (e.g. [

Beelen et al. 2023]), the aim is not to

“correct”, but to identify

how such processes and layers manifest in the collections in question. Furthermore,

we are not merely users of archival data; we are also actively involved in making

the

archival record more visible (or ‘louder’) in the digital space (Johnson, 2017). For

instance, we make decisions about modelling the data and solving problems related

to

resource constraints when obtaining source data ([

Drobac et al. 2023b]).

This article discusses materials that mainly comprise person and family collections

held in private archival organisations. These collections are widely used by scholars

and favoured as case studies in archival research [

Edquist 2021], yet

they are rarely considered in postcolonial and other critical approaches. As a case

study, we have created a virtual archive of

“epistolary

women”. Our analyses suggest that the collections available to us as linked

data are relatively representative of the upper echelons of nineteenth-century

society. However, it is more difficult to assess whether the proportion of female

person-actors (29% of all actors and 26–34% of the more filtered group of records

creators in two sample organisations) accurately represents women’s epistolary

activities. Nevertheless, network analysis indicates that the available epistolary

metadata reflects changes in women’s societal roles brought about by modernisation.

This demonstrates that even partial datasets can reveal significant historical

phenomena and be profitably used by humanists, provided the gaps or ‘missingness’

are

understood and acknowledged [

Ryan and Ahnert 2021].

In addition, we have identified certain epistemic silences: women who do not feature

in our current research canon but who have substantial archival collections that

could offer valuable insights into a variety of historical topics. Overall, the

results are tentative but promising. However, we must bear in mind that the current

data include four online publications of letters and letter metadata from only nine

cultural heritage organisations – albeit the largest and most central – and only from

those collections that have been indexed at the level of individual letter exchanges.

Nonetheless, despite all the gaps and omissions discussed in this paper, the

collected metadata provides the most comprehensive sample available of who actually

sent and received letters in nineteenth-century Finland.

This article has demonstrated the potential of linked open data and critical

collection history in identifying gendered structures within epistolary metadata

collections. In the future, we can continue to explore women’'s correspondence as

a

historical phenomenon by focusing more qualitatively on the women we identify using

data-driven methods. Furthermore, we can direct our historical research towards

archival collections as the outcome of specific political, cultural, and

socio-economic pressures – pressures that leave their mark, turning the archives

themselves into artefacts of history [

Burton 2005, 6]. To achieve

this, we should digitise the acquisition registers of various organisations and study

their decision-making processes relating to archival appraisal where possible. While

many organisational histories touch on these issues – most recently [

Hakala 2023] study of the Swedish Literature Society in Finland’s

archival collections – a combined history focusing on private epistolary collections

as a case study remains to be written. A critical collection history is also always

a

history of the construction of collective identity; it can reveal whose experiences

are available to us as historians, and also whose experiences have been narrativised

as history at different stages in the past.

Appendix 1: Survey about the current situation of letter metadata held by Finnish

cultural heritage organisations

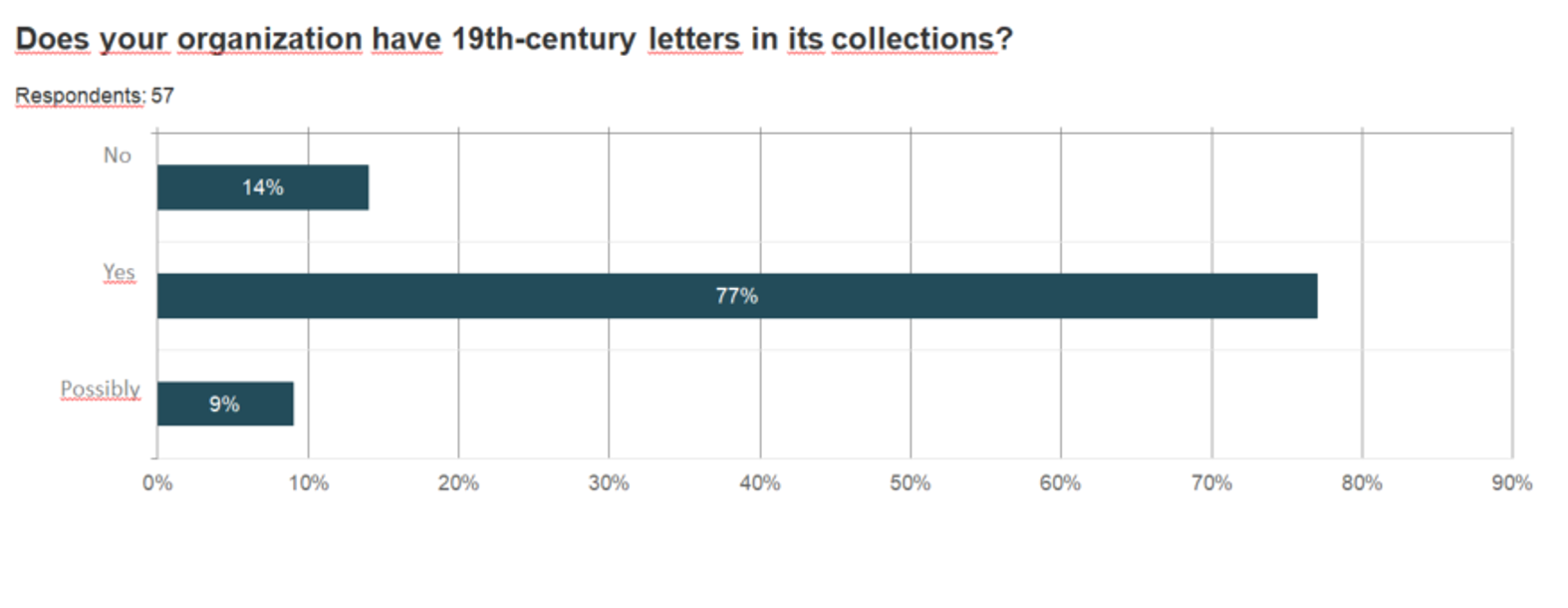

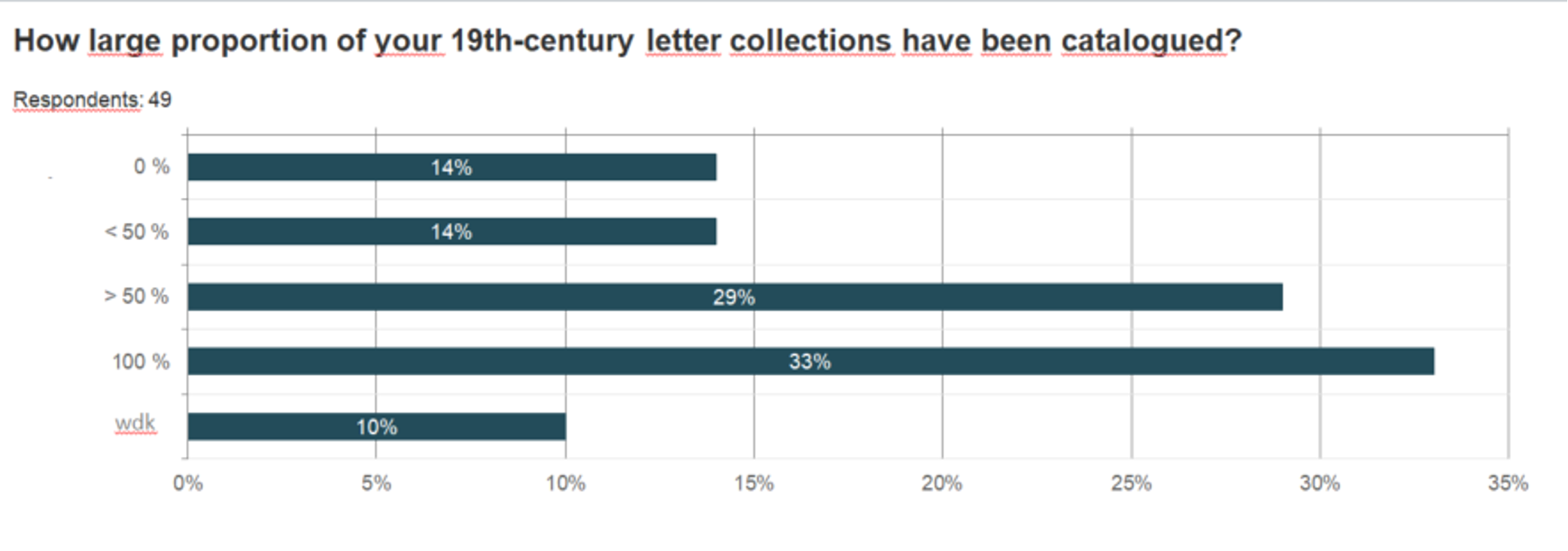

The project Constellations of Correspondence – Large and Small

Networks of Epistolary Exchange in the Grand Duchy of Finland (CoCo) has

launched a survey on nineteenth-century letter collections in Finnish cultural

heritage organisations. To date, 57 archives, libraries and museums have responded.

The survey contains 18 questions to help understand the current situation and the

challenges of aggregating collection metadata. Here, we present results relevant to

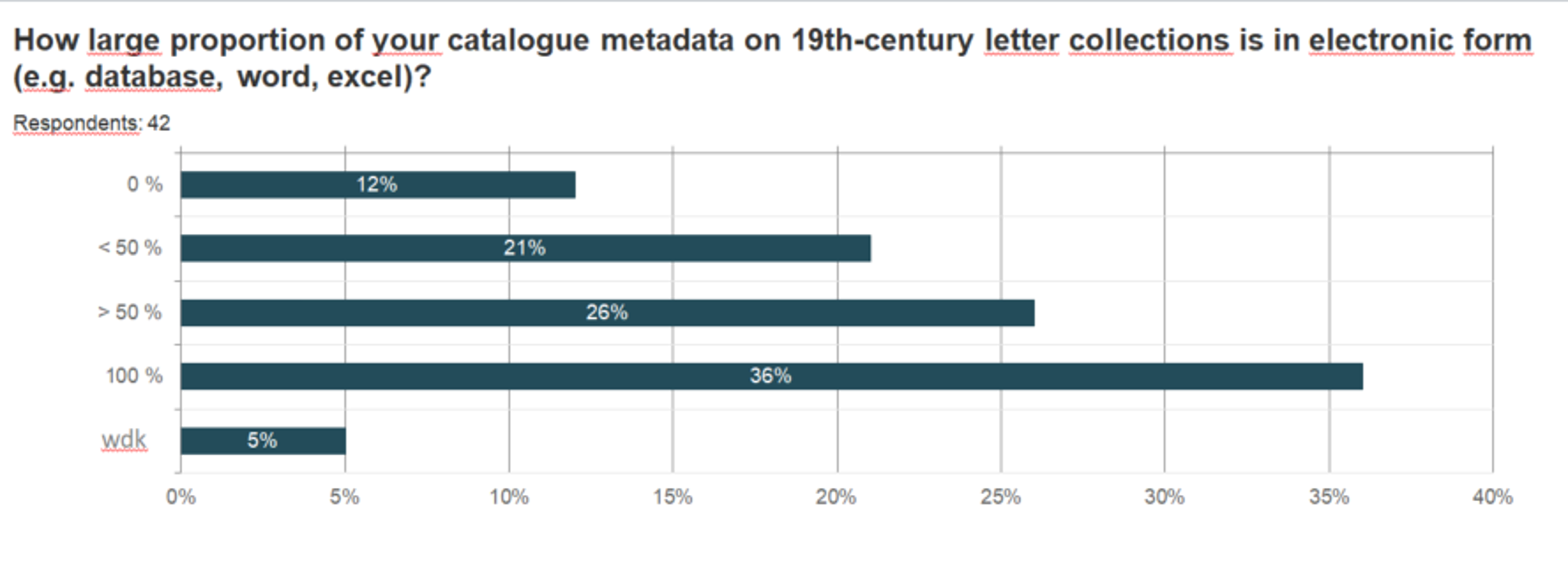

this paper in Figures 6-8. In summary, 86% of respondents either have or possibly

have nineteenth-century letters in their archival collections. The word ‘possibly’

is

explained by the fact that only 33% have catalogued all their letters. Conversely,

14% have not catalogued them at all. Regarding archival finding aids, only 36% of

respondents with nineteenth-century letters have catalogues in electronic form, such

as databases, Excel files, or Word documents. This makes the content

machine-readable, but additional structuring and harmonising is required.

Appendix 2: Top 10 male and female authors in the complete correspondence network

based on degree (non-weighted), 1830–1860 and 1880–1910.

| Name |

Degree rank and value (non-weighted) |

Occupations |

Archives |

records creator |

External links (in Wikipedia) |

| Lönnrot, Elias (1802–1884) |

1 (266) |

author, botanist, collector, folklorist, full professor, hymnwriter,

lexicographer, linguist, pedagogue, philologist, physician, physician writer,

poet, professor, writer |

AEL, ELL, FNG, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SKS, SLS, ÅA |

archive (ELL) |

11 (yes) |

| Armfelt, Alexander (1794–1875) |

2 (135) |

minister-secretary, count, chancellor |

AEL, FNG, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SLS, ÅA |

yes (FNA) |

9 (yes) |

| Topelius, Zachris (1818–1898) |

3 (125) |

amanuensis, author, children’s writer, full professor, historian, history

teacher, journalist, poet, professor, rector, school teacher, writer |

AEL, ELL, FNG, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ZTS, ÅA |

archive (ZTS) |

9 (yes) |

| Ilmoni, Immanuel (1797–1856) |

4 (125) |

director, full professor, Master of Philosophy, physician, professor,

prosector, secretary, senior accountant |

ELL, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SKS) |

7 (yes) |

| Gottlund, Carl Axel (1796–1875) |

5 (119) |

author, explorer, historian, lecturer, linguist, translator, writer |

ELL, FNG, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (NLF, SKS) |

6 (yes) |

| Mannerheim, Karl Gustaf (1797–1854) |

6 (111) |

count, County governor, doctor of both laws, entomologist, judge,

notary |

JVSL, NAL, NLF, ÅA |

yes (NLF) |

9 (yes) |

| Cygnaeus, Fredrik (1807–1881) |

7 (104) |

author, docent, full professor, historian, literary critic, poet, rector,

school teacher, writer |

AEL, ELL, FNG, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SKS, ÅA |

yes (NLF) |

11 (yes) |

| Runeberg, Johan Ludvig (1804–1877) |

8 (87) |

author, school teacher, full professor, journalist, priest, lecturer |

AEL, ELL, FNG, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SLS) |

10 (yes) |

| Schauman, Berndt Otto (1821–1895) |

9 (87) |

amanuensis, intendant, member of the Diet of Finland, non-fiction writer,

politician, writer |

AEL, ELL, FNG, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (NLF) |

8 (yes) |

| Rein, Gabriel (1800–1867) |

10 (83) |

member of Diet ofFinland, historian, full professor, rector, lecturer |

AEL, ELL, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SKS, ÅA |

yes (NLF) |

8 (yes) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

Appendix 2, Table 4. Ten authors with highest degree (non-weighted) in

1830–1860. Source: LetterSampo Finland dataset (19 February 2025). Note: The information

about

occupations, archive, fonds, and external links concerns all letters by the

author. AEL (Albert Edelfelt’s Letters), ELL (Elias Lönnrot’s Letters), JVSL

(Johan Vilhelm Snellman’s Letters), FNG (The Finnish National Gallery), SKS (The

Finnish Literature Society), NAF (The National Archives of Finland), NLF (The

National Library of Finland), SLS (The Swedish Literature Society in Finland), ÅA

(The Åbo Akademi University Library).

| Name |

Degree rank and value (non-weighted) |

Occupations |

Archives |

records creator |

External links (in Wikipedia) |

| Runeberg, Fredrika (1807–1879) |

61 (25) |

writer, journalist, novelist, editor |

AEL, ELL, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SLS) |

10 (yes) |

| Gadd, Carolina Lovisa (1810–1867) |

81 (19) |

- |

NLF |

no |

1 (no) |

| Tengström (Bergbom), Johanna Carolina (1803–1885) |

98 (16) |

- |

JVSL, NLF, SLS, ÅA |

no |

4 (no) |

| Armfelt, Wava |

108 (15) |

- |

ÅA |

family (ÅA) |

0 (no) |

| Collan (Wasenius), Johanna (1814–1901) |

115 (14) |

- |

NLF, ÅA |

son (NLF) |

4 (no) |

| Tengström (Kellgren), Anna Sofia (1826–1906) |

118 (14) |

- |

JVSL, NLF, SLS |

husband (NLF) |

4 (no) |

| af Brunér, Emma (1814–1857) |

119 (14) |

- |

ÅA |

no |

2 (no) |

| Blomqvist, Elisabeth (1827–1901) |

132 (12) |

director, head teacher, painter, painter and varnisher |

AEL, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

family (NLF) |

6 (yes) |

| von Haartman, Naema Aurora (1822–1866) |

135 (12) |

- |

NLF, ÅA |

family (ÅA) |

4 (no) |

| Westzynthius (Haartman), Margaretha Sophia (1807–1894) |

146 (11) |

- |

ÅA |

no |

1 (no) |

Table 5.

Appendix 2, Table 5. Ten female authors with highest betweenness in 1830–1860.

Source: LetterSampo Finland dataset (19 February 2025). Note: The information about

occupations,

archive, fonds, and external links concerns all letters by the author.

| Name |

Degree rank and value (non-weighted) |

Occupations |

Archives |

records creator |

External links (in Wikipedia) |

| Mechelin, Leopold (1839–1914) |

1 (528) |

banker, deputy, director, doctor of both laws, entrepreneur, full professor,

politician |

AEL, FNG, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SKS, SLS, ÅA |

yes (NAF) |

10 (yes) |

| Palmén, Ernst Gustaf (1849–1919) |

2 (476) |

historian, member of parliament, member of the Diet of Finland, politician,

professor |

AEL, FNG, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (NLF) |

9 (yes) |

| Topelius, Zachris (1818–1898) |

3 (473) |

amanuensis, author, children’s writer, full professor, historian, history

teacher, journalist, master’s degree, poet, professor, rector, school teacher,

writer |

AEL, ELL, FNG, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ZTS, ÅA |

archive (ZTS) |

9 (yes) |

| Schybergson, Magnus Gottfrid (1852–1925) |

4 (356) |

historian, full professor |

AEL, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (ÅA) |

8 (yes) |

| Setälä, Emil Nestor (1864–1935) |

5 (333) |

anthropologist, Chancellor, diplomat, linguist, member of parliament,

Minister for Foreign Affairs of Finland, Minister of Education, politician,

senator, university teacher |

NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SKS) |

9 (yes) |

| Aspelin-Haapkylä (Aspelin), Eliel (1847–1917) |

6 (325) |

art historian, full professor, counselor of state |

AEL, ELL, FNG, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SKS) |

8 (yes) |

| Colliander, Otto Immanuel (1848–1924) |

7 (305) |

bishop, politician, priest |

AEL, FNG, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (NAF) |

8 (yes) |

| Cygnaeus, Gustaf (1851–1907) |

8 (269) |

journalist, lecturer, newspaper editor |

AEL, FNG, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (ÅA) |

6 (yes) |

| Schauman, Berndt Otto (1821–1895) |

9 (252) |

amanuensis, intendant, member of the Diet of Finland, politician,

writer |

AEL, ELL, FNG, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (NLF) |

8 (yes) |

| Palmén, Johan Axel (1845–1919) |

10 (238) |

member of Diet of Finland, full professor, ornithologist, entomologist,

geographer |

NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (NLF) |

7 (yes) |

Table 6.

Appendix 2, Table 6. Ten authors with highest degree (non-weighted) in

1880–1910. Source: LetterSampo Finland dataset (19 February 2025). Note: The information

about

occupations, archive, fonds, and external links concerns all letters by the

author.

| Name |

Degree rank and value (non-weighted) |

Occupations |

Archives |

records creator |

External links (in Wikipedia) |

| Aalberg, Ida (1857–1915) |

21 (182) |

actor, stage actor, theatrical director |

AEL, FNG, NAF, NLF, SKS, ÅA |

yes (FNL) |

7 (yes) |

| Gripenberg, Aleksandra (1857–1913) |

31 (157) |

member of parliament, writer, editor, chairperson |

NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SKS) |

7 (yes) |

| Käkikoski, Hilda (1864–1912) |

40 (145) |

member of parliament, politician, teacher, writer |

NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SKS) |

6 (yes) |

| Friberg, Maikki (1861–1927) |

60 (114) |

editor, journalist, suffragist, teacher, writer |

NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (NAF) |

5 (yes) |

| Westermarck, Helena (1857–1938) |

63 (112) |

editor, historian, painter, painter and varnisher, visual artist,

writer |

FNG, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (ÅA) |

7 (yes) |

| Söderhjelm, Alma (1870–1949) |

68 (103) |

author, docent, essayist, full professor, historian |

AEL, FNG, NAF, NLF, SKS, SLS, ÅA |

yes (ÅA) |

8 (yes) |

| Talvio, Maila (1871–1951) |

79 (95) |

writer, translator, honorary doctorate |

NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SKS) |

7 (yes) |

| Ackté, Aino (1876–1944) |

83 (90) |

opera singer, librettist |

AEL, FNG, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (FNL) |

9 (yes) |

| Elfving (Runeberg), Lina (1841–1916) |

89 (84) |

- |

AEL, FNG, NLF, SLS, ÅA |

husband (SLS) |

3 (no) |

| Åström, Emma Irene (1847–1934) |

91 (83) |

lecturer, school teacher, teacher |

NAF, NLF, SKS, ÅA |

yes (ÅA) |

6 (yes) |

Table 7.

Appendix 2, Table 7. Ten female authors with highest degree (non-weighted) in

1880–1910. Source: LetterSampo Finland dataset (19 February 2025). Note: The information

about

occupations, archive, fonds, and external links concerns all letters by the

author.

Appendix 3: Top 10 female authors in the correspondence network with only women

based on degree (non-weighted), 1830–1860 and 1880–1910

| Name |

Degree rank and value (non-weighted) |

Occupations |

Archives |

records creator |

External links (in Wikipedia) |

| Runeberg, Fredrika (1835–1857) |

1 (8) |

writer, journalist, novelist, editor |

AEL, ELL, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SLS) |

10 (yes) |

| Tallqvist, Alina Fredrika (1835–1899) |

2 (8) |

- |

NAF, NLF |

no |

4 (no) |

| af Brunér, Emma (1814–1857) |

3 (8) |

- |

ÅA |

no |

2 (no) |

| Westzynthius (Haartman), Margaretha Sophia (1807–1894) |

4 (6) |

- |

ÅA |

no |

1 (no) |

| Westzynthius, Emilia Teodora (Emmy) (1835–1906) |

5 (6) |

- |

ÅA |

no |

3 (no) |

| von Haartman, Naema Aurora (1822–1866) |

6 (6) |

- |

NLF, ÅA |

family (ÅA) |

4 (no) |

| Thuneberg, Yolanda Aurora (1826–1888) |

7 (6) |

- |

NAF, NLF, ÅA |

family (NLF) |

3 (no) |

| Collan (Wasenius), Johanna (1814–1901) |

8 (6) |

- |

NLF, ÅA |

son (NLF) |

4 (no) |

| Tengström (Kellgren), Anna Sofia (1826–1906) |

9 (6) |

- |

JVSL, NLF, SLS |

husband (NLF) |

4 (no) |

| Blomqvist, Elisabeth (1827–1901) |

10 (5) |

director, head teacher, painter, painter and varnisher |

AEL, JVSL, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

family (NLF) |

6 (yes) |

Table 8.

Appendix 3, Table 8. Ten authors with highest degree (non-weighted) in the

letter network containing only women, 1830–1860. Source: LetterSampo Finland dataset

(19 February 2025).

Note: The information about occupations, archive, fonds, and external links

concerns all letters by the author.

| Name |

Degree rank and value (non-weighted) |

Occupations |

Archives |

records creator |

External links (in Wikipedia) |

| Gripenberg, Aleksandra (1857–1913) |

1 (96) |

member of parliament, writer, editor, chairperson |

NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SKS) |

7 (yes) |

| Friberg, Maikki (1861–1927) |

2 (71) |

editor, journalist, suffragist, teacher, writer |

NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (NAF) |

5 (yes) |

| Käkikoski, Hilda (1864–1912) |

3 (71) |

member of parliament, politician, teacher, writer |

NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (SKS) |

6 (yes) |

| Westermarck, Helena (1857–1938) |

4 (55) |

editor, historian, painter, painter and varnisher, visual artist,

writer |

FNG, NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (ÅA) |

7 (yes) |

| Åkerman, Emma (1851–1931) |

5 (52) |

poet, teacher, writer |

NAF, NLF, SKS |

family (NLF) |

8 (yes) |

| Aalberg, Ida (1957–1915) |

6 (51) |

actor, stage actor, theatrical director |

AEL, FNG, NAF, NLF, SKS, ÅA |

yes (FNL) |

7 (yes) |

| Elfving (Runeberg), Lina (1841–1916) |

7 (49) |

- |

AEL, FNG, NLF, SLS, ÅA |

husband (SLS) |

3 (no) |

| Söderhjelm, Alma (1870–1949) |

8 (41) |

author, docent, essayist, full professor, historian |

AEL, FNG, NAF, NLF, SKS, SLS, ÅA |

yes (ÅA) |

8 (yes) |

| Hagman, Lucina (1853–1946) |

9 (39) |

chairperson, head teacher, member of parliament, politician, professor,

teacher, women’s rights activist, writer |

NAF, NLF, SLS, SKS, ÅA |

yes (NAF) |

7 (yes) |

| Åström, Emma Irene (1847–1934) |

10 (37) |

lecturer, school teacher, teacher |

NAF, NLF, SKS, ÅA |

yes (ÅA) |

6 (yes) |

Table 9.

Appendix 3, Table 9. Ten authors with highest degree (non-weighted) in the

letter network containing only women, 1880–1910. Source: LetterSampo Finland dataset

(19 February 2025). Note: The information about occupations, archive, fonds, and external

links

concerns all letters by the author.

Acknowledgments

Computing resources of the CSC – IT Center for Science were used in our work.

Works Cited

Ahnert and Ahnert 2019 Ahnert, R. and Ahnert,

S. E. (2019)

“Metadata, surveillance and the Tudor

state”,

History Workshop Journal, 87, Spring

2019, pp. 27–51. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dby033 (Accessed: 28 June 2024).

Ahnert et al. 2020 Ahnert, R. et al. (2020)

The network turn: Changing perspectives in the

humanities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108866804 (Accessed: 06 February 2024).

Ahola et al. 2025 Ahola, A., Björklund, M., Drobac, S., Enqvist, J., Hyvönen, E. A., Jauhiainen, I.,

Kanervo, S., Koho, M., Koho, O., Kukkonen, V., Leal, R., Leskinen, P., La Mela, M.,

Paloposki, H.-L., Pikkanen, I., Poikkimäki, H., Rantala, H., Sainio, S., Tuominen,

J., & Wahjoe, M. F. (2025)

LetterSampo Finland (1.0.0) [Data set]. Zenodo.

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15210590.

Autio 1997a Autio, V.M. (1997a)

“Reuter, Enzio” in

Kansallisbiografia-verkkojulkaisu ('National Biography of Finland',

online publication). Studia Biographica 4. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden

Seura. Available at:

http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:sks-kbg-006353 (Accessed: 05 July 2024).

Autio 1997b Autio, V.M. (1997b)

“Reuter (1600–)” in

Kansallisbiografia-verkkojulkaisu ('National Biography of Finland',

online publication). Studia Biographica 4. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden

Seura. Available at:

http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:sks-kbg-008049 (Accessed: 05 July 2024).

Beelen et al. 2023 Beelen, K. et al. (2023)

“Bias and representativeness in digitized newspaper

collections: Introducing the environmental scan”,

Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 38(1), pp. 1–22. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqac037 (Accessed: 14 April 2024).