Making Sense of the Emergence of Manslaughter in British Criminal Justice

Abstract

Manslaughter emerged as a new and distinct category of crime amongst those tried at the Old Bailey in London in the first half of the nineteenth century. From being a rare charge in 1800, manslaughter came to represent over 60% of all trials for ‘killing’ by the 1850s. This article describes the methodologies used by the authors to explore this phenomenon via trials included in the Old Bailey Online. It details the use of unsupervised clustering, embeddings and relevance measures to map the changing language associated with the charge of manslaughter; and more importantly, describes the application of top-down ‘sense making’ methodologies to the resulting analysis. Along the way it argues for the importance of including qualitative judgements by subject specialists in the process of developing quantitative analyses. Inter Alia it suggests that the rise of manslaughter was the result of a complex set of forces including changing statute law, the rise of a professional police, changes in the administration of coroners’ courts, and a growing public intolerance of violence.

Introduction

Methods

Case Study – Manslaughter at the Old Bailey

On the Wilkinson trial, I can see why the TF-IDF came up as an accident, and I suspect I was second guessing the text myself. There are two things that made me label it a fight. First, the quantity of blood; and second, the general rush to declare it an accident. In my experience it is pretty hard to kill yourself by accidentally falling over and hitting your head on a ledge halfway up a wall (I have tried); and if you do manage it, getting blood all over the place seems odd. And if it was an accident, why did Wilkinson not call out, and instead waited until the watchhouse keeper came down 45 minutes after putting Wilkinson in the cell? And if the dead guy could chat with three different people in the three weeks before his death, including about the seriousness of his wound, why he didn’t say something about how it happened, is just a bit weird. Just looking at the account, it feels like the sort of thing where there were lots of opposing narratives presented at the coroner’s inquest (hence the trial), that gradually got edited out on the way to court. On the face of it, there is no obvious reason it has come to trial at all. But again, I suspect that this is just me second guessing!

Historical Significance

Conclusion

Appendix

Table of Annotations

| "t18300218-65", watchhouse cell fight, involving two men, with hospital surgeon giving evidence. Defendant does not give evidence. NG. |

| "t18300708-65", male lodger kills housekeeper's 4-year-old daughter by giving her a large glass of rum. Apothecary gives evidence. Defendant gives evidence briefly. NG. |

| "t18300708-71", two men, skittle ground, drunken argument, - a surgeon gives evidence. Defendant does not give evidence. NG. |

| "t18310908-226", Coronation Day fireworks, 10-year-old boy knocked down; accidental discharge of a gun held by a man, leads to his death. Surgeon gives evidence. Defendant does not give evidence. NG. |

| "t18311020-150", Man throws mattress & bed clothes out window – along with his infant female child – domestic violence, some drink. A surgeon gives evidence. Defendant does not give evidence. Guilty – Transportation for life. |

| "t18311201-125", Fight among ostler and coachman, in a stable yard. Surgeon gives evidence. Defendant does not give evidence. Guilty. Fined 1s. |

| "t18320216-114", Female customer kills a pub landlady, by pulling here down. Surgeon gives evidence. Defendant gives evidence. Guilty – 1 year confinement. |

| "t18330214-131", Death by drinking brandy at a public house – testing whether he was coaxed to do so. The defendant appears to be the landlord but does not give evidence. Medical student gives evidence. NG. |

| "t18330411-209", An apparent mix up in prescriptions leads to a woman being given a large dose of prussic acid, which kills her. A medical malpractice case made up primarily of medical witnesses? The defendant does not give evidence. NG. |

| "t18330905-126", Mother accused of killing her infant child through neglect/starvation. Primarily medical evidence. The defendant does not give evidence. NG. |

| "t18340220-80", Man forced to drink large amounts of alcohol, on a boat, later dies. Defendant does not give evidence. No medical evidence. NG. |

| "t18340410-187", Drunken pub altercation. Two men. Defendant does not give evidence. No medical evidence. Guilty – 3 months |

| "t18340410-189", Woman kills a female child – issues of neglect, bruising, and an underlying medical condition. A lot of medical evidence. The defendant does not give evidence. NG. |

| "t18340904-160", Mother accused of scalding her child, who later dies. A lot of medical evidence. The defendant does not give evidence. NG. |

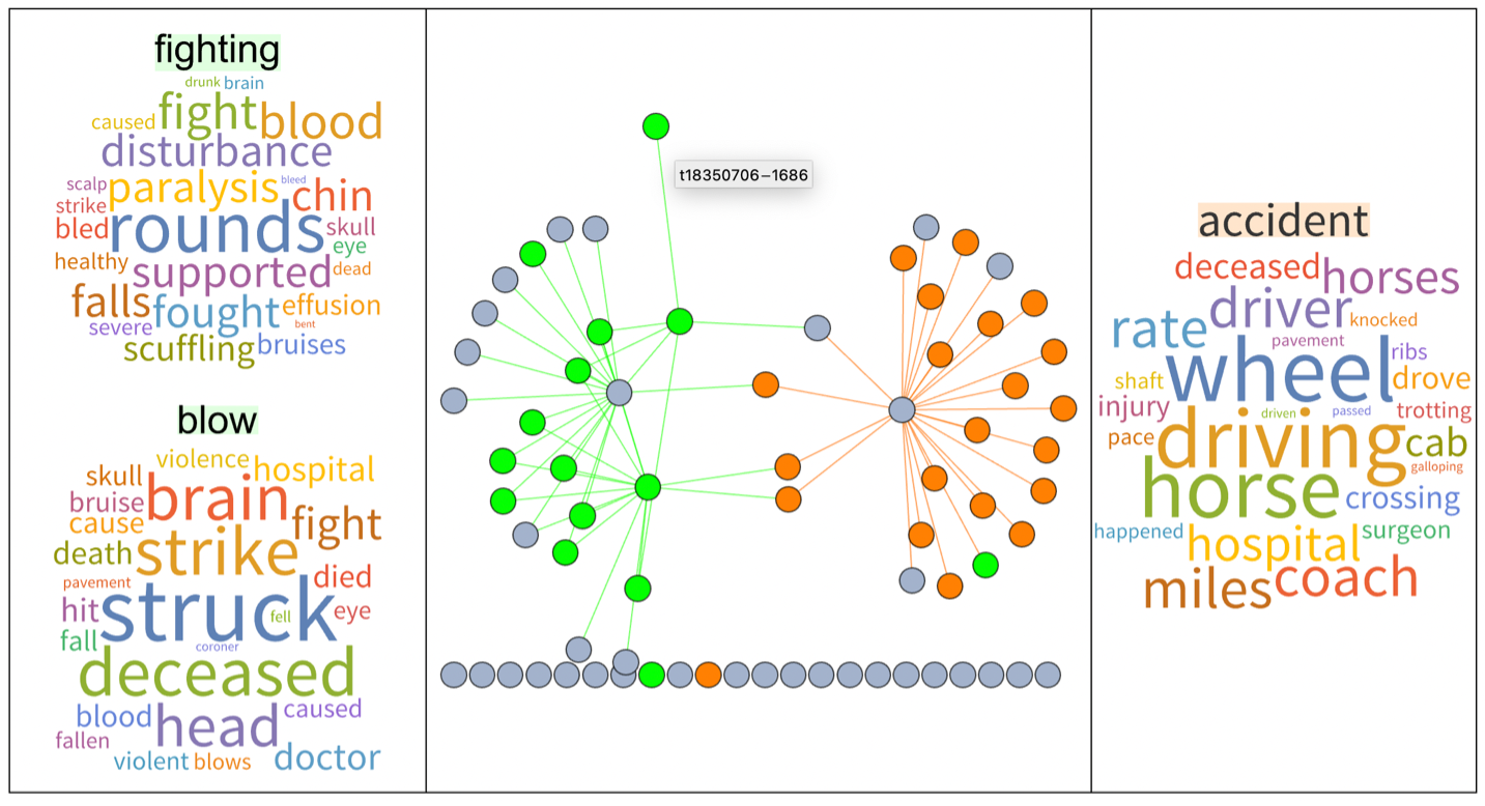

| "t18350706-1686", A rather formal fight with ‘seconds’. Two male defendants, who do not give evidence. Some medical evidence. ‘Acquitted’ tagged as NG. |

| "t18350817-1883", Domestic violence, wife dies following a fight, with alcohol abuse involved. A fair amount of medical evidence. The defendant does not give evidence. Guilty – 1 year. |

| "t18350921-1938", Pub fight involving two men. Starts with medical evidence. Defendant doesn’t give evidence. NG. |

| "t18351123-150", Workhouse death where a female nurse (probably ward nurse), assaults a 77-year-old man. He dies several days later. A lot of medical evidence. The defendant does not give evidence. NG. |

| "t18360229-723", Widowed mother of two boys, kills the younger one with a poker blow to the head. Older child the main witness (v. affecting). A lot of medical evidence. Guilty. Fined 1s. |

| "t18360919-2160", Husband accused, following his wife falling into a fit and dying. Some medical evidence. Defendant does not give evidence. NG. |

| "t18361024-2373", Two very drunk men, in a pub fight. Strong medical evidence. Defendant does not give evidence. Guilty, Fined 1s. |

| "t18361128-208", A fight on a boat in harbour between two men; also involves striking a dog and the body ending in the river. No medical evidence, but a lot on how the main blow was struck (i.e. which hand etc). The defendant does not give evidence. Guilty – Confined one week. |

| "t18300415-168", Traffic accident involving two very posh coaches and some drunkenness. Defendant and victim both male. No medical evidence. No Defendant statement. NG. |

| "t18300527-112", Traffic accident – with lots of witnesses; quite long. Defendant and victim both male. 7 lines of medical testimony. No defendant statement. NG. |

| "t18300916-252", Traffic accident, involving a lot of drink and some malice. Numerous witness statements, and some medical testimony. Defendant and victim both male. No defendant statement. Widow asked that the body not be opened ‘if it could be avoided’. NG. |

| "t18301028-176", A traffic accident, with a doctor on the scene almost immediately. This is a long account with numerous witness statements, including several from doctors, etc. Defendant and victim both male. The defendant does not give evidence. NG. |

| "t18310217-104", A VERY long medical malpractice case involving a post treatment infection leading to death. All the evidence is essentially medical in character. The victim in female, defendant male. There is a long defendant statement that claims there is a professional rivalry, and a good dozen character witnesses. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_St._John_Long NG. |

| "t18310908-219", A long, detailed traffic accident case – good on the rules of the road. Defendant and victim both male. Minimal medical testimony; no defendant’s testimony. NG. |

| "t18311201-161", Traffic accident. A short account, female victim, male cab driver. No medical testimony but includes brief defendant’s statement. NG. |

| "t18320906-104", Traffic accident involving a painter up a ladder (knocked over by a dray). Long, with numerous witness statements, and a short bit of medical evidence. Male defendant and victim. The defendant makes a short statement. NG. |

| "t18321129-53", A traffic accident involving an elite female victim. Long, with numerous witness statements, and some medical testimony. Male defendant does not make a statement. NG. |

| "t18330411-184", Long traffic accident case, involving two omnibuses and a road worker. Both defendant and victim were male. Includes a defendant statement but no medical evidence. Does mention deodands. Guilty 3 months. |

| "t18330704-129", Traffic accident, curds and whey seller, female, killed by male cart driver. Numerous witnesses, but not long. Some medical evidence. NG. |

| "t18330905-198", Traffic accident involving a 6-year-old girl, and a male omnibus driver. Long, with numerous witness statements; including an extended defendant statement. Short medical testimony. NG. |

| "t18340220-48", Traffic accident involving a cab – both victim and defendant are male. A long case with numerous witnesses, and an extended defendant’s statement. Guilty 1 year. |

| "t18340904-157", Traffic accident involving a male cab driver, and a 6-year-old female victim. Long, with numerous witness statements, and a short bit of medical testimony. Defendant gives brief statement. Guilty 9 months. |

| "t18340904-158", Traffic accident, medium length, male victim and defendant. No defendant statement, some medical testimony. Guilty 3 months in Newgate. |

| "t18341124-164", Traffic accident involving an overloaded cart. Both victim and defendant are male. The case is a long one with numerous witnesses, including a brief bit of medical testimony, and a very short defendant statement. Guilty – 1 month. |

| "t18341124-191", Traffic accident, male defendant, male victim. Quite long with 5 witnesses. No medical evidence or defendant statement. Guilty |

| "t18350615-1520", - a fight between three men, in a domestic context involving a poker and a sword – mistaken initially as a ‘domestic’. A very long trial, with a lot of medical evidence, including the claim that an amputation shortened the victim’s life – and is mentioned by the jury at the end. Guilty x2, Judgement Respited. |

| "t18350817-1910", Traffic accident – a couple crossing the road, hit by a cab, killing the husband. Reasonably long, but relatively few witnesses. No Defendant’s statement, and one medical witness. Guilty, 2 months. 6th Jury, Common Sergeant. |

| "t18350921-2013", Traffic accident involving a cab – male defendant, elderly male victim. Long, including numerous witnesses, the defendant’s statement, and some medical evidence. Guilty, 6 months. 3rd jury, Recorder. |

| "t18351026-2288", Traffic accident, involving a cart. Male defendant and victim. Long, with numerous witnesses, some medical evidence and a defendant’s statement. Not Guilty. 2nd Jury, Recorder. |

| "t18351123-131", Shipping accident on the Thames at Deptford. Male victim, male defendant. Long detailed statement from the second mate – but no other witnesses. Medium length. No medical testimony, or Defendant’s statement. NG. |

| "t18300527-161", Very short, Male defendant accused of killing his wife (I assume). Dismissed after limited medical evidence. NG. |

| "t18300708-134", A short trial, revolving around a blow made by a potboy to a porter in a pub. Female pub landlady only witness, with evidence of remorse etc. Victim died 8 weeks after incident. No medical evidence. NG. |

| "t18310217-208", Very short, Male defendant accused of killing his wife (I assume). Dismissed after limited medical evidence. NG. |

| "t18311020-105", A stub – ‘the offence having been committed in ‘Kent, the witnesses were not examined’. NG. |

| "t18320906-103", Very short. A husband and wife appear to be charged with killing their child. A ‘bad’ inquisition leads to acquittal. NG. |

| "t18320906-262", Very short, Male defendant accused of killing his wife (I assume). Dismissed after limited medical evidence. NG. |

| "t18321129-156", Very short, Male defendant accused of killing a woman with a different last name. Dismissed after limited medical evidence. NG. |

| "t18341205-338", Thirteen words – male defendant, male victim, no evidence. NG |

| "t18300916-152", Medium length trial, of a soldier who kicks a young girl who had been playing on some ‘chains’. No medical evidence, or statement from the defendant. Issues of identifying the girl and soldier. NG. |

| "t18300916-154", Medium to long trial, male defendant and victim. Death occurs a while after the def. shoves the victim, who falls over and hurts his hip – later dying of dysentery. Lots of medical evidence, no defendant statement. NG. |

| "t18301028-112", see above t18310217-104. Another VERY long medical malpractice case involving the same defendant, and a post treatment infection leading to death. All the evidence is essentially medical in character. The victim in female, defendant male. There is a long defendant statement that claims there is a professional rivalry, and a good dozen character witnesses. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_St._John_Long |

| "t18310106-88", Medium length trial, involving an elderly woman being frightened, bricks through windows, and white sheets. She dies three months later. Defendant male, victim female, some medical testimony. NG. |

| "t18310630-65", Medium length, involving a street fight between two men. There is some medical evidence. Guilty. 6 months. |

| "t18320105-213", A fight between a building labourer and an elderly man, in a small court. Involves a large crowd, cry of murder and about four weeks between assault and the victim’s death. Guilty. 12 months. |

| "t18320517-119", Two women assault a third woman, who dies the next morning. There is some question of whether a true bill had been found. After initial witness statements most of this long trial is given over to medical testimony from half a dozen doctors. NG. |

| "t18320705-112", A female neighbour kills a 6-month-old boy, by dropping a box, that knocks the child from its grandmothers arms. The child dies immediately. A lot of witnesses, medium length. A short defendant statement. Guilty. 1 month. |

| "t18320906-102", Two sisters in law – one assaulting the other. Lots of witnesses. Some medical evidence determining ‘natural causes’. NG. |

| "t18320906-161", A very long trial in which one of twelve cannons ordered to celebrate the Reform Act, blows up on firing, killing someone. Defendant is the cannon maker. Lots of technical evidence on making cannons, from a lot of witnesses. No medical evidence or defendant’s statement. Guilty. 10 days. |

| "t18320906-257", Two youngish boys charged with the death of a third. Takes place in a paper manufacturing, and involves a steam engine (the victim is exposed to the vented steam). A long, case with lots of witnesses. Some medical evidence suggesting steam could cause ‘excitement’ of the brain. The victim dies a week after the main event. Not guilty. |

| "t18321129-154", Medium length. A late-night drunken brawl involving around five men. Both defendant and victim are men. A fair number of witnesses, including two doctors. Guilty 2 months. |

| "t18321129-155", Medical malpractice, with a female medical practitioner contributing to the death of a 3-year-old girl, with a scorbutic disease. Revolves around the use of a plaster. Lots of medical evidence, and long statements from the parents. Written statement from the defendant. NG. |

| "t18330103-177", Following a christening, the parents are on a pub crawl, are thrown out by the bartender, and the child is hit by the door and dies. Quite short, with strong medical evidence. NG. |

| "t18340703-102", Medium to long trial. Two couples get into a fight on the street; one man is killed, and his wife badly beaten. Both the men and women involved, but the defendant and victim are both male. Lots of witnesses, some medical testimony. Guilty. 3 months. |

| "t18340703-103", A street fight, male defendant and victim. Defendant claims his mother was insulted, and he struck out. Involves drink, honour and random violence. Some medical testimony. Longish trial. NG. |

| "t18340703-145", A drunken fight outside a pub on payday. Reasonably long, with both male and female witnesses. No medical evidence. NG. |

| "t18350615-1464", Male defendant and victim. A fight on shipboard, as the ship is being brought into a dock. A trip, an open-handed blow and a knife. Longish, with quite a few witnesses, and some medical testimony. Guilty 1 Year. |

| "t18350706-1682", A man and woman, an unmarried couple, get in a fight with a soldier outside a pub, leading to the soldier’s death. Longish, with long statements. Some medical evidence. NG. |