Abstract

This paper attempts to construct a virtual space of possibilities for the

historical embedding of the human figure, and its posture, in the visual arts by

proposing a view-invariant approach to Human Pose Retrieval (HPR) that resolves

the ambiguity of projecting three-dimensional postures onto their

two-dimensional counterparts. In addition, we present a refined approach for

classifying human postures using a support set of 110 art-historical reference

postures. The method’s effectiveness on art-historical images was validated

through a two-stage approach of broad-scale filtering preceded by a detailed

examination of individual postures: an aggregate-level analysis of

metadata-induced hotspots, and an individual-level analysis of topic-centered

query postures. As a case study, we examined depictions of the crucified, which

often adhere to a canonical form with little variation over time — making it an

ideal subject for testing the validity of Deep Learning (DL)-based methods.

1. Introduction

As early as 1884, the French physiologist Étienne-Jules Marey (1830–1904)

invented

chronophotography to derive human motion only from points

and lines. He dressed his subjects in dark suits, with metal buttons at the

joints connected by metal stripes and photographed them with a camera that

captured multiple exposures on a single, immobile plate. In so doing, he

introduced the human skeleton as an objectified distillation of

“pure movement”

[

McCarren 2003, p.29], emphasizing only trajectory snapshots of points and

lines, eliminating inherently human features, such as skin and muscle; it is

“visually unmoored from bodies and space,” as Noam M. Elcott [

Elcott 2016, p. 24] put it. By abstracting the human form, as Marey demonstrated, we are

prompted to inquire about the intrinsic qualities that remain when the body is

stripped of its psychological and most physical identifiers. This theme of

abstraction has been a recurring element in art history, a discipline inherently

linked to the visual, where the human form not only is a subject of

representation but a

carrier of meaning — along with the body

movements and postures that emanate from it [

Egidi et al. 2000].

However, art history has emphasized gesture, which pertains to localized

movements of body parts — especially the head and hands — rather than posture,

which, as in Marey’s chronophotography, describes the entire body’s stance,

extending beyond the upper extremities to also include the lower body (see e.g.,

[

Gombrich 1966]

[

Baxandall 1972]). Acknowledging this historical perspective on

abstraction informs our methodology in this paper, which employs

state-of-the-art

Human Pose Estimation (HPE) and

Human Pose

Retrieval (HPR) techniques to capture — and analyze — posture in its

full complexity.

[1] By leveraging computational methods that echo Marey’s

trajectory snapshots, we intend to better understand both the universal and

culturally specific aspects of the human form.

Specifically, this paper harnesses the ‘artificial eye’ of computational

methodologies to construct a

virtual space of possibilities — of

associations, references, and similarities — for the historical embedding of the

human figure, and its posture, in the visual arts. By explicitly applying

state-of-the-art HPE and HPR methods, we bridge the gap between traditional

historical analysis and modern computational approaches. In this context, we

argue for the integration of both

close and

distant

viewing, where the global analysis of

distant viewing

logically precedes and enhances the localized, detailed analysis of

close

viewing — i.e., the qualitative analysis of individual artworks

within their spatio-temporal contexts.

[2] From a computational point of view, the approach

first

estimates joint positions of human figures,

keypoints (Figure 1), that resemble Marey’s metal buttons, to

create a vector representation,

embedding, of the human skeleton,

which is then utilized to

retrieve figures of potential relevance —

with two postures considered similar if they represent variations of the same

action or movement. To this end, we utilize a view-invariant embedding,

following the methodology proposed by [

Liu, T. et al. 2022], that projects

three-dimensional postures onto their two-dimensional counterparts, recognizing

that postures can be visually identical but mathematically distinct, depending

on the observer’s perspective.

Although embeddings derived from neural networks — or more generally:

Deep

Learning (DL) methods — have proven beneficial for various

art-historical retrieval tasks (e.g., [

Ufer et al. 2021]

[

Karjus et al. 2023]

[

Offert and Bell 2023]) by capturing semantically pertinent information

within dense vector spaces, their practical inspection remains underexplored in

scholarly discourse. While previous research has provided the groundwork for

DL-based retrieval, our study narrows the focus by specifically investigating

HPR applications. This leads us to our main research question:

How can the perceptual space of embeddings, obtained by DL models, be explored

and interpreted? What spatial patterns emerge within these spaces, and to what

extent can they encode posture?

Put simply, we determine how DL techniques can be leveraged to systematically

explore the representation of posture. We outline that, in their current state,

such methods can serve as

recommender systems in art-historical

posture analysis, but also in related fields — such as theatre and dance studies

— that critically examine human posture and movement. To this end, we introduce

a two-stage approach of broad-scale filtering preceded by a detailed examination

of individual postures: an aggregate-level analysis of metadata-induced

hotspots, and an individual-level analysis of topic-centered query postures.

Both pipelines are intended, at least in this paper, to reaffirm the embedding

space’s usefulness in art-historical research, rather than to discover novel

art-historical knowledge. Our study, therefore, is designed to synthesize DL

methods into a unified workflow, easily adaptable to other disciplines, enabling

scholars to potentially trace the evolution of posture in art-historical

objects, allowing a thorough exploration of their

“underlying psychic

structures” [

Butterfield-Rosen_2021, p. 21]. As a concrete example, our case

study focuses on depictions of the crucified. These depictions, while globally

diverse, often adhere to a

“canonical” form that exhibits little variation

over time — characterized by specific positions of Christ’s head and the arch of

his torso — making them an ideal subject for testing the validity and

transferability of DL-based posture analysis that is accessible even to

non-experts in the field.

Methodologically, the paper thus contributes to the field of

Digital Art

History (DAH), which has grown considerably since Johanna Drucker in

2013 criticized the delayed advent of computational methods for art-historical

inquiry, despite the increasing availability of suitable data in online

repositories [

Drucker 2013]. Section 2 first discusses related

work. In Section 3, we introduce our proposed methodology that processes images

of human figures into a machine-readable format. This involves first abstracting

the figures’ postures into skeletal representations and then converting these

into robust, view-invariant posture embeddings suitable for retrieval and

classification tasks. Section 4 elaborates on the data set used for interaction

with and exploration of the embedding space during the case study’s inference

phase. The case study itself is detailed in Section 5 and extensively discussed

in Section 6. The paper concludes with Section 7, which summarizes the findings

and discusses future research directions.

2. Related Work

Art-historical research has emphasized the analysis of gesture, a semantically

charged sub-category of bodily movement, over posture — influenced by the

Renaissance’s re-invigoration of scholarly rhetoric [

Zimmerman 2011, p. 179].

For instance, Ernst Gombrich in 1966 suggested that gestures in the visual arts

originate from natural human expressions that have been ritualized, thus

acquiring unique forms and meanings [

Gombrich 1966]. In

particular, Warburg’s concept of

Pathosformeln

contributed significantly to the discourse: by identifying formally stable

gestures from antiquity that were in the Renaissance repeatedly employed to

express primal emotions [

Warburg 1998]. Nevertheless, Emmelyn

Butterfield-Rosen advocates for posture as a

“more useful category” for

exploring

“permanent, underlying psychic structures” [

Butterfield-Rosen_2021, p. 21]. Already in the early 20th century, the Finnish art historian Johan Jakob

Tikkanen proposed a typology of leg postures as

“cultural motifs” in the visual

arts [

Tikkanen 1912]; these motifs, according to Tikkanen, have

evolving functions that may be traced through European art from antiquity to

modernity. Despite, or perhaps because of, Tikkanen’s own admission of the

typology’s limitations and his insistence on a multidisciplinary approach to

better understand the evolution of motifs, his work has remained largely

unrecognized in academic discourse, often relegated to the footnotes (see, e.g.,

[

Steinberg 2018, p. 200] [

Butterfield-Rosen_2021, p. 279]).

In response, recent efforts have employed digital methods to the large-scale

investigation of art-historical posture. Yet, the adoption of HPE methods

remains limited: on the one hand, due to significant variations in human

morphology between artistic depictions and real-world photography, and, on the

other hand, due to the absence of domain-specific, annotated data required to

train neural networks. Predominantly, existing approaches [

Impett and Süsstrunk 2016] [

Jenícek and Chum 2019] [

Madhu_2020] [

Zhao, Salah, and Salah 2022] therefore utilize models trained on real-world photographs without

integrating art-historical material. Only recently, [

Springstein et al. 2022]

and [

Madhu et al. 2023] have begun to refine model accuracy by fine-tuning with

domain-specific images — an approach we also leverage in this paper. To then

assess how similar these machine-abstracted postures are to every other posture

in a data set,

low-level approaches obtain scores directly from

keypoint positions (or angles) using numerical similarity metrics [

Kovar, Gleicher, and Pighin 2002] [

Pehlivan and Duygulu 2011]. However, as

morphological or perceptual features cause variations in keypoint positions [

Harada et al. 2004]

[

So and Baciu 2005], which may affect the reliability of similarity metrics

even between identical postures,

high-level approaches have begun

to exploit the latent layers of neural networks [

Rhodin, Salzmann, and Fua 2018]

[

Ren et al. 2020]. Given the task-specific nature of these latent

representations, [

Liu, J. et al. 2021] suggest normalized posture features

that are invariant to morphological structure and viewpoint; however, the method

relies on fully estimated postures without missing keypoints. Following the

strategy of [

Liu, T. et al. 2022], called

Probabilistic View-invariant

Pose Embedding (Pr-VIPE), we instead propose a solution that is not

only robust to occlusion,

[3] but also easily adaptable to various domains.

3. Methodology

The proposed methodology transforms images of human figures into a

machine-readable format by first simplifying their postures into skeletal

representations. These skeletal models eliminate non-essential visual

information — such as background scenery and clothing — so that only the body’s

posture is retained. Each posture is then numerically encoded as an array of

real numbers, referred to as an embedding, which compresses

postural specifics and enables similar postures to be retrieved across a large

collection of artworks. Consequently, the embedding represents a distilled

version of the original figure, while the embedding space constitutes a

virtual space of possibilities, i.e., of all conceivable

postures. The overall architecture of this pipeline is shown in Figure 2.

3.1. View-invariant Human Posture Embedding

To make posture recognition more accurate, we follow an approach inspired by

[

Springstein et al. 2022] that integrates

Semi-supervised

Learning (SSL). This means that our system learns from both

labeled and unlabeled images, allowing it to improve over time by generating

its own training data. We implement the regression-based

Pose

Recognition Transformer (PRTR), as outlined by [

Li et al. 2021], which employs a cascaded Transformer architecture

with separate components for bounding box and keypoint detection [

Vaswani et al. 2017]

[

Carion et al. 2020].

[4] The

proposed methodology for HPE thus leverages a

top-down

strategy: In the first stage, human figures are localized within an

image by rectangular bounding boxes, which are then examined in the second

stage to identify keypoints, i.e., points relevant to the abstraction of the

figures’ posture.

The estimated whole-body posture is segregated into the upper and lower body,

shown in green and red, respectively, in Figure 3; these components, along

with the whole body, then comprise the search query employed for retrieval

purposes. The lower body is composed of six keypoints (ankles, knees, hip)

and the upper body of eight keypoints (hip, wrists, elbows, shoulders). This

division increases the reliability of the system: Even if the whole-body

posture cannot be detected (e.g., due to missing or obscured joints), the

upper and lower body may still provide enough information to accurately

classify the figure. In the next step, configurations exceeding 50% of the

maximum possible keypoints are filtered to eliminate configurations with

high uncertainty. Valid configurations are then projected into

320-dimensional embeddings using the Pr-VIPE proposed by [

Liu, T. et al. 2022].

[5]

Unlike methods that depend solely on keypoint positions, Pr-VIPE encodes the

appearance of a posture — as perceived by humans — so that it remains robust

to changes in perspective, allowing similar postures to be compared across

different viewpoints. It does so by mapping each two-dimensional posture

into a probabilistic embedding space where the representation is not a fixed

point, but a probability distribution. During training, the system is

exposed to pairs of two-dimensional postures obtained from different camera

views, often augmented by synthesizing multi-view projections from

three-dimensional keypoints. The learning objective encourages the

embeddings of postures that are visually similar (i.e., represent the same

underlying three-dimensional posture) to be close to each other in the

probabilistic space — even if there are perspective-induced variations in

the two-dimensional keypoint positions.

[6]

3.2. One-shot Human Posture Classification

To classify postures, the pipeline is as follows: We first manually identify

110 art-historical images with reference postures of human figures and label

them with keypoints. We then re-use the Pr-VIPE and compute the cosine

distances between the embeddings, associating each query to the closest

matching reference posture(s). This allows a fine-grained indexing of

postures, even when the body parts of each configuration could not be

adequately estimated. At the same time, there is no fixed, semantically

dubious categorization into groups, as is the case with agglomerative

clustering methods [

Impett and Süsstrunk 2016]. However, as shown in

Figure 3, where example images of the reference postures are shown, a single

human figure can only model a fraction of the high postural variability

within the subnotations.

The selected postures, derived from the Iconclass taxonomy [

van de Waal 1973], range from elementary configurations, such as

“arm raised upward,” to

complex full-body arrangements, such as

“lying on one side, stretched out,”

reducing the limitations of culturally or temporally dependent labels.

Iconclass, while explicitly designed for the iconography of Western fine

art, also includes universal definitions ranging from natural phenomena to

anatomical specifics, the latter of which are pertinent not only to our

research but also potentially beneficial for scholarly investigations into

human anatomy across various disciplines, such as dance studies. Each

definition within the Iconclass taxonomy is represented by a unique

combination of alphanumeric characters, referred to as the ‘notation,’ and a

description, the ‘textual correlate,’ accompanied by a set of keywords. A

notation consists of at least one digit symbolizing the first level of the

hierarchy, ‘division.’ This may be followed by another digit at the

secondary level, and one or two (identical) capital letters at the tertiary

level. The structure, referred to as the ‘basic notation,’ can be further

supplemented with auxiliary components [

van Straten 1994]. We

consider four groups of Iconclass notations: notation

31A23 (textual

correlate

“postures of the human figure”),

31A25 (

“postures and gestures of

the arms and hands”),

31A26 (

“postures of the legs”), and

31A27 (

“movements

of the human body”). Notations

31A23 and

31A27 represent the whole body,

31A25 the upper body, and

31A26 the lower body. Each group is almost equally

represented: upper-body notations with 31 instances, lower-body notations

with 25, and whole-body notations with 27 each.

4. Data Set

Using the Wikidata SPARQL endpoint,

[7] we extract 644,155 art-historical

objects classified as either

“visual artwork” (Wikidata item

Q4502142) or

“artwork series” (

Q15709879) that have a two-dimensional image.

[8] For

these objects, our model identifies 9,694,248 human figures, which are — after

the filtering stage — reduced to 2,355,592 figures.

[9] Wikidata was chosen primarily for practical reasons: It surpasses

other art-related databases that are limited by institutional and regional

focus, like that of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Moreover, unlike distributed

image archives such as Europeana,

[10] where considerable effort is

required to filter out reproductions of the same original, Wikidata is

continuously updated, reducing the number of near-duplicates and thus increasing

the reliability of the data.

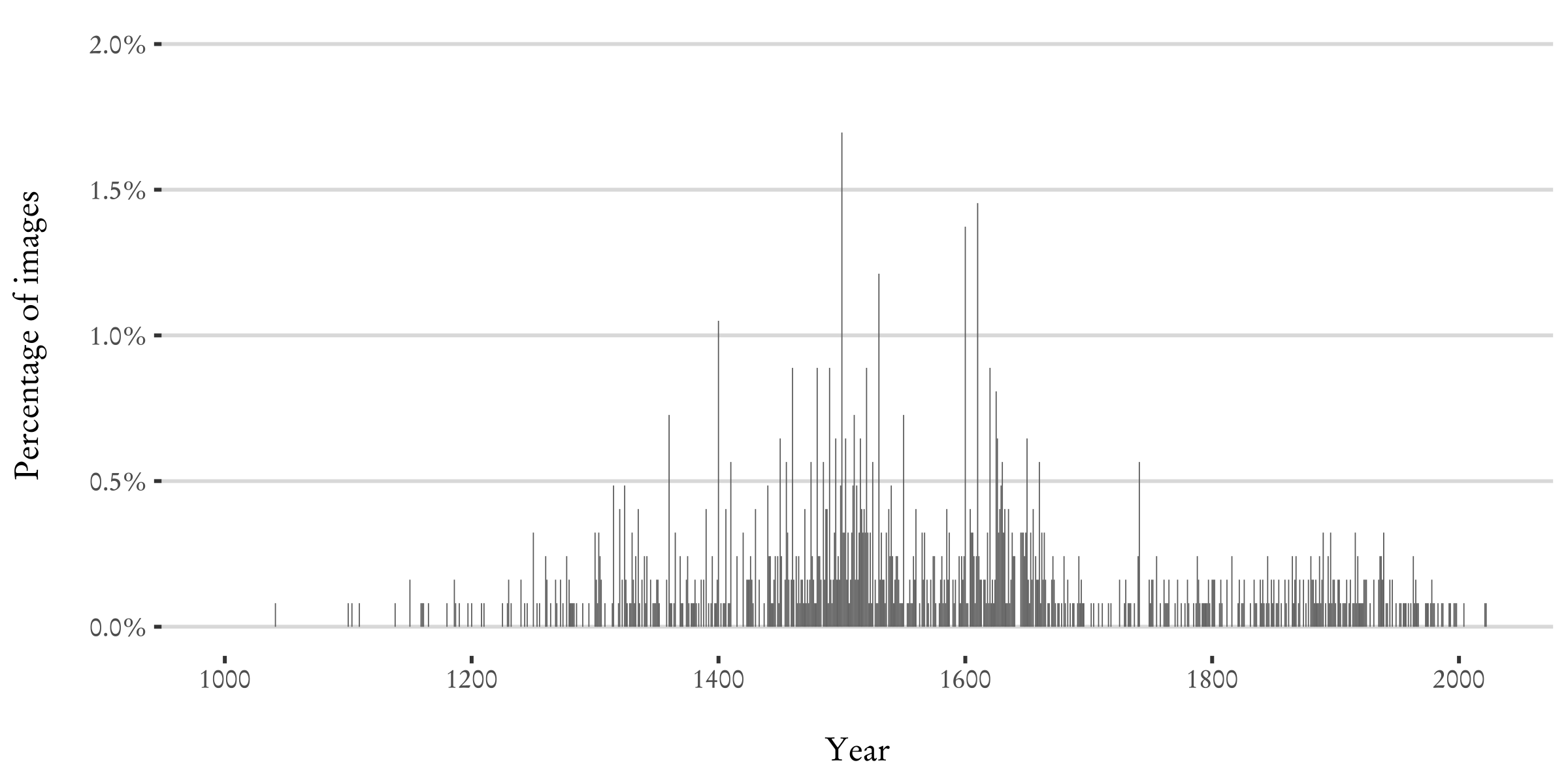

We determine the objects’ creation dates based on the earliest probable date and

ending with the latest. As shown in Figure 4a, using only the starting point of

the interval causes many data points to converge around the turn of the

centuries, leading to an inaccurate peak in the number of objects. To overcome

this, we employ bootstrapping: For the 71.9% of objects with defined time

intervals, we randomly select a point within the time interval over

50 iterations and calculate the average number of objects per time point. This

method is valuable for all types of objects that are dated by time intervals, as

is common in historical research. In addition, it enables the creation of

so-called confidence intervals, which reflect the natural

uncertainty in the dating of historical objects. The result, as shown in

Figure 4b, provides a better understanding of the potential density of objects

in different time periods: There is a continuous increase in the number of

objects after 1400, with isolated peaks around 1500 and 1650. More dominant

peaks appear only around 1900, with a pronounced one between 1935 and 1940,

largely due to the collecting activities of the National Gallery of Art that is

featured prominently in Wikidata.

Filtering the Wikidata data set for the term “crucifix” and its French and German

translations yields a subset of 1,516 objects for the case study (Figure 7 in

Appendix A). Most of these objects are labeled as paintings (65.1%), prints

(6.3%), or sculptures (4.4%), with crucifixes themselves accounting for 4.2%.

Featured are works from artists such as El Greco (1541–1614; 33 objects),

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641; 19 objects), and Lucas Cranach the Elder

(1472–1553; 17 objects); 32.7% of the objects are without attribution. Of

course, not all human figures depicted in these metadata-selected objects are

crucified, as we filter solely for terms related to crucifixion scenes, not for

figures depicted as crucified.

5. Case Study

In the following, we outline two analytical pipelines for exploring the

constructed embedding space as a virtual space of possibilities: a

distant viewing focused on an aggregate-level analysis of

metadata-induced hotspots, and a close viewing focused on an

individual-level analysis of topic-centered query postures.

5.1. Analytical Process

The first pipeline entails filtering objects based on their metadata, in

particular the Wikidata “depicts” property (P180) and labels in English,

French, and German. Objects containing any of the query terms are selected

and then analyzed for their spatial position within the embedding space to

identify density structures — the metadata-induced density peaks are thus

utilized for the distant viewing of objects whose postures

closely resemble those pre-selected by the metadata. Each point in the

embedding space denotes a unique posture, with density referring to how

these points are grouped — either clustering in high-density areas or

scattering in low-density regions. The second pipeline is predicated on the

density peaks identified at the aggregate level; it focuses on the

recognition and exploitation of individual postures associated with specific

iconographies, thus enabling a posture-to-posture search. This

involves a close viewing of objects that are visually related

to the identified query postures; it also explores the developmental

trajectories of different postures within the embedding space to trace the

‘evolution’ of iconographic elements.

Our case study examines the variability in the representation of the

crucified. It focuses specifically on the depiction of the crucified Christ,

excluding accompanying figures traditionally portrayed at the cross’s base,

such as Mary and Christ’s disciples — especially the apostle John. Although

depictions of the crucified Christ vary widely throughout the world,

influenced by local and ethnic traditions, they are generally unified by a

“canonical” form:

“dead upon the Cross, Jesus’s head is slung to

one side, typically our left; his torso is naked and upright, sometimes

slightly arched” [

Merback 2001, p. 69].Variations in the positioning of Christ’s limbs are subtly evident in

different artistic traditions: Gothic crucifixes, for instance, show Christ

in a dynamic, bent position, with legs thrust forward and knees spread [

Brandmair 2015, p. 100], while in Italian iconography,

Christ is often depicted with upward-angled arms, his head slumped on his

chest, with varying leg positions to represent the deceased body’s movement

[

Haussherr 1971, p. 50].

To conduct a qualitative analysis, the embedding spaces of the embeddings are

reduced from 320 to two dimensions. Traditional dimension reduction

techniques such as

t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding

(t-SNE) [

van der Maaten and Hinton 2008],

Uniform Manifold

Approximation and Projection (UMAP) [

McInnes 2018], and their variants (e.g., [

Im, Verma, and Branson 2018]

[

Linderman et al. 2019]) are known to preserve either local or

global spatial relationships, which can result in the formation of

artificial clusters that are not present in the original data.

[11] To overcome this limitation, we employ

Pairwise Controlled Manifold Approximation (PaCMAP), which

first identifies global structures and then refines them locally [

Wang et al. 2021]. We re-use the Pr-VIPE model checkpoints from [

Liu, T. et al. 2022].

[12] To analyze the density structure of

the embedding spaces, and thus the

virtual space of

possibilities, we employ three visualization techniques: scatter

plots, two-dimensional histograms, and contour plots (Figure 5). Both

histograms and contour plots employ a color gradient ranging from blue

(denoting lower concentrations) to red (denoting higher concentrations),

with white signifying the midpoint. Contour plots are often favorable

because of their superior ability to discern isolated high-density areas

clearly; however, smaller, less dense regions are more reliably identified

in two-dimensional histograms. Further details of the techniques are given

in Appendix B.

5.2. Aggregate Level

The embedding space is structured so that similar postures are grouped

closely together. This proximity implies that finding a posture in a

particular region of the embedding space generally means that another

similar posture can be found nearby — hence, semantic groups of postures

typically cluster, providing a structured approach to efficient retrieval

based on these spatial concentrations, as will be discussed in the

following. In each case, our analysis begins with an examination of the

embedding spaces for all images to establish a baseline understanding. We

then narrow our focus to compare these embedding spaces with those

containing only crucifixion scenes, in order to determine how particular

thematic elements influence the spatial organization within the

embedding.

5.2.1. Whole-body posture embedding

The distribution within the two-dimensional whole-body posture embedding

space of all images is characterized by a significant concentration in

the upper-left quadrant, with density gradually decreasing towards the

southern regions (Figures 5a, b, and c). The upper-right quadrant, while

also densely populated, features a slightly downward-shifted center of

density, aligning it more centrally within the embedding space; it

mostly features postures in which the upper arms or thighs are

perpendicular to the upper body. In contrast, postures with nearly

extended arms or legs dominate the middle-lower quadrant, exemplified by

notation 31A2363 (“Lying on one side, stretched out”).

In addition, manual inspection of the whole-body embedding space reveals

two primary cluster-like formations that correspond mainly to specific

configurations of the upper and lower body — which is noteworthy given

that we are not focusing here on the upper-body and lower-body

embeddings. In the lower segment, we identify figures classified with

subnotations under 31AA2511 (“Arm raised upward – AA – both arms or

hands”), including T- or Y-shaped crucified ones in the lower-central area (31A237,

“Hanging figure”). Those stretching sideways or backwards are centered

with a downward tilt, mapped to the subnotations 31A2513 (“Arm stretched

sidewards”) and 31A2514 (“Arm held backwards”). The upper-left segment

is dominated by configurations of the lower body. For instance, the

standing figure with straight legs is prominent in the upper left,

identified as 31A26111 (“Standing or leaning with both legs straight,

side by side, feet flat on the ground”); she is usually depicted with

her arms held down. A third segment in the upper-right quadrant features

postures with bent limbs that is particularly difficult to capture

semantically; it includes the subnotations 31A234 (“Squatting, crouching

figure”) and 31A235 (“Sitting figure”). The center’s less dense regions

frequently show errors in HPE that cannot be meaningfully

classified.

In the crucifixion’s embeddings, a compact hotspot is centrally situated

at the bottom, indicating specific posture configurations that differ

substantially from other configurations in the data set, with lesser

populated zones in the remaining embedding space, as evident in

Figures 5d, e, and f. The sparsity of data in other areas is primarily

related to objects associated with terms relevant to crucifixion scenes,

as opposed to crucified figures themselves; naturally, not all human

figures depicted in the metadata-selected objects are crucified, given

the large number of figures involved in these scenarios. The utility of

hotspot post-filtering becomes apparent when comparing the postures in

images labeled with “crucifix” to those labeled and within the hotspot

located at the central bottom. Notable are Iconclass notations with a

clear emphasis on upper-body positions, such as 31A2364 (“Lying on one

side, with uplifted upper part of the body and leaning on the arm”) and

31A23711 (“Hanging by one arm”).

5.2.2. Upper-body posture embedding

In the two-dimensional upper-body posture embedding space, we observe a

singular high-density region towards the lower center (Figures 5g, h,

and i). This area, with its circular shape, implies a central group of

similar upper-body postures in the data set. Elsewhere, the embedding

space exhibits a gradient of posture densities with no other significant

hotspots, suggesting a more dispersed representation of upper-body

postures; this pattern is likely due to the limited number of eight

keypoints used in the embedding, which reduces the variation between

postures. The lower center of the embedding space contains mostly

postures with one arm bent in front of or behind the body.

[13] In the lower-left quadrant,

postures often feature an arm bent upwards, as indicated by notation

31A2513 (

“Arm stretched sidewards”).

The distinct posture of the crucified — with arms outstretched sidewards

— is validated in the two-dimensional upper-body posture embedding space

by a small, elongated high-density area in the lower central region

(Figures 5j, k, and l). This area corresponds with the high-density

region of the notation 31AA2513 (“Arm stretched sidewards – AA – both

arms or hands”). When examining the distribution of the upper-body

similarities, there are only slight variations between images labeled

“crucifix” and the data set’s remainder, due to the large spread of

points in the embedding space. Yet, differences are evident when

considering dominant Iconclass notations compared to the general

population: Notations such as 31A2531 (“Hand(s) bent towards the head”)

and 31AA2514 (“Arm held backwards – AA – both arms or hands”) have

notably higher similarity values in the metadata- and hotspot-filtered

subset.

5.2.3. Lower-body posture embedding

The configuration of hotspots in the lower-body posture embedding space

of all images is mostly elongated and narrow, suggesting a linear

progression of posture similarities (Figures 5m, n, and o). The contour

lines in the lower-body posture embedding follow a sinusoidal pattern,

with pronounced peaks and valleys — maybe reflecting an inherent data

structure where certain lower-body positions are more common, and others

less so. The lower-right quadrant of the embedding space is dominated by

postures with straight or slightly bent legs. In contrast, the

upper-left quadrant mostly features postures with more significantly

bent legs, encompassing squatting and various sitting positions, such as

notation 31A26123 (“Squatting with legs side by side”).

Subtle but discernible shifts compared to the density structure of the

overall data set are observed in the crucifixion’s lower-body embedding

only at the sinusoidal pattern’s edges, particularly in the central left

and right quadrants, with a slight downward extension in the right

quadrant (Figures 5p, q, and r). The infrequency of leg positions that

uniquely denote crucified figures, as evidenced by the rarity of

hotspots, confirms the lack of specific leg configurations in these

depictions, which often resemble normal standing positions with slightly

bent legs. This absence of specific configurations in the iconography

compared to the broader data set is further accentuated when assessing

lower-body posture similarities: There are extensive overlaps between

the Iconclass notations, like those of the upper-body similarity

distributions.

5.3. Individual Level

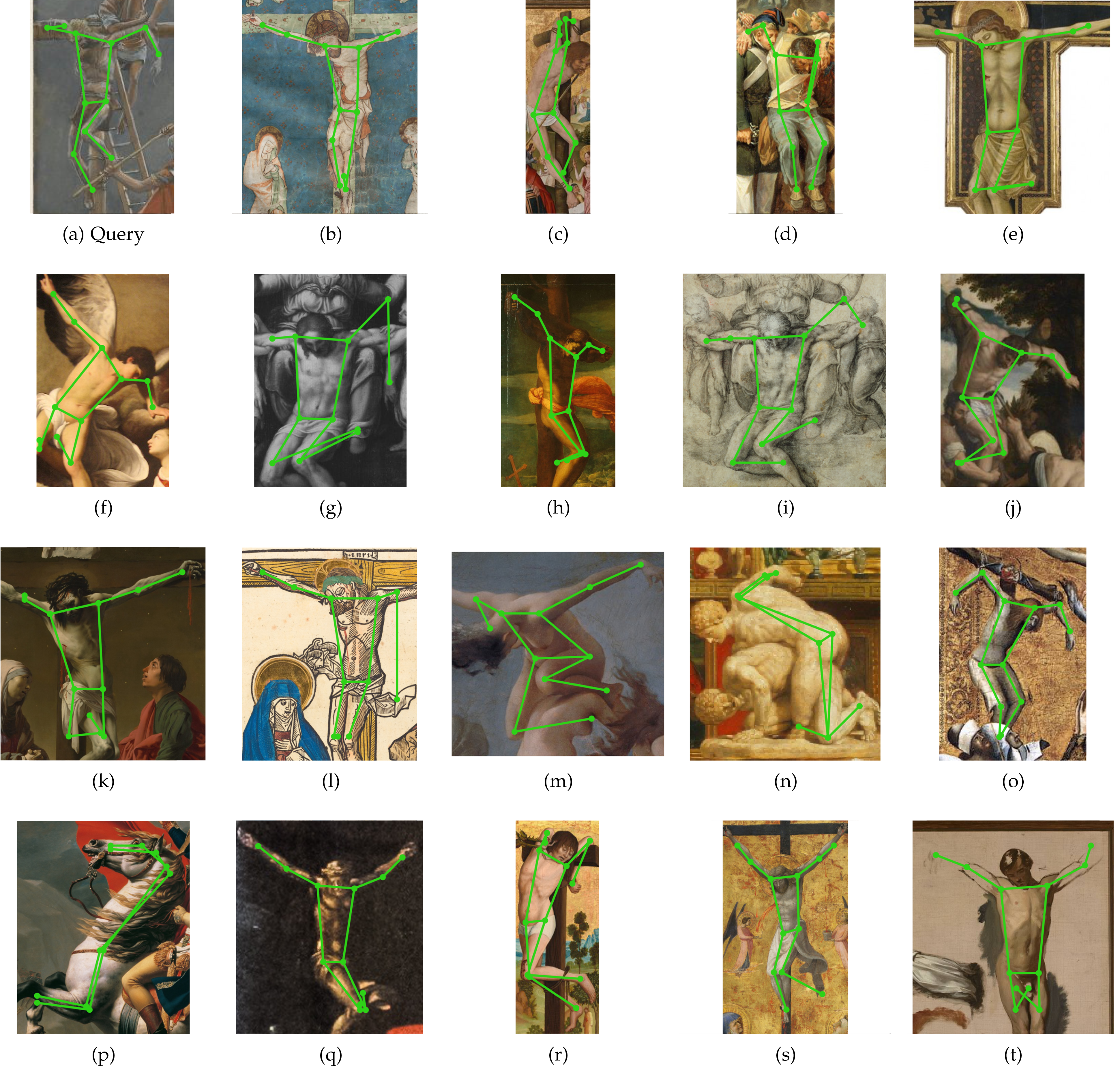

In the second pipeline, our approach departs from the broad analysis of

metadata-induced hotspots and instead focuses on the in-depth study of

individual artworks and their comparative analysis based on the generated

embeddings. To this end, we implement an approximate

k-nearest neighbor graph,

Hierarchical Navigable Small

World (HNSW) [

Malkov_2020], which

contains the 320-dimensional embeddings of the whole body, upper body, and

lower body. To illustrate its practical application, we examine James

Tissot’s

The Strike of the Lance (1886–1894)

and more specifically, the thief crucified to Christ’s right (Figure 6a). As

shown in Figure 6, the thief’s bent arm is echoed in the Pietà, for instance

in a rendition after Marcello Venusti (c. 1515–1579; Figure 6g), where Mary

is portrayed mourning her son. Interestingly, the horse’s upright stance in

Jacques Louis David’s

Napoleon on the Great St

Bernard (1801; Figure 6p) is mistakenly recognized as a human

figure — with outstretched arms and bent legs — echoing the thief’s posture;

this error results from imprecise bounding box detection, which frequently

misclassifies animals with human-like physiognomies as human figures.

Misalignments of the lower body are evident also in works such as Perino del

Vaga’s

A Fragment: The Good Thief (Saint Dismas)

(c. 1520–1525; Figure 6h), Hendrick ter Brugghen’s

The

Crucifixion with the Virgin and St John (1625; Figure 6k), and Jan

de Hoey’s

Ignatius of Loyola (c. 1601–1700;

Figure 6r), primarily with inaccurately shortened ankles, which also trace

back to limitations in bounding box detection. Despite these issues, minor

inaccuracies, such as the misestimation of the left wrist in Figure 6l, seem

to not affect the retrieval performance. The degree of keypoint

misestimation is proportional to its effect on the generated feature vector,

which is essential for accurate retrieval. Even when keypoints are grossly

misestimated, as shown in Figure 6l, the model only marginally penalizes

these errors in the resulting embedding, provided that the majority of

keypoints are estimated with sufficient accuracy.

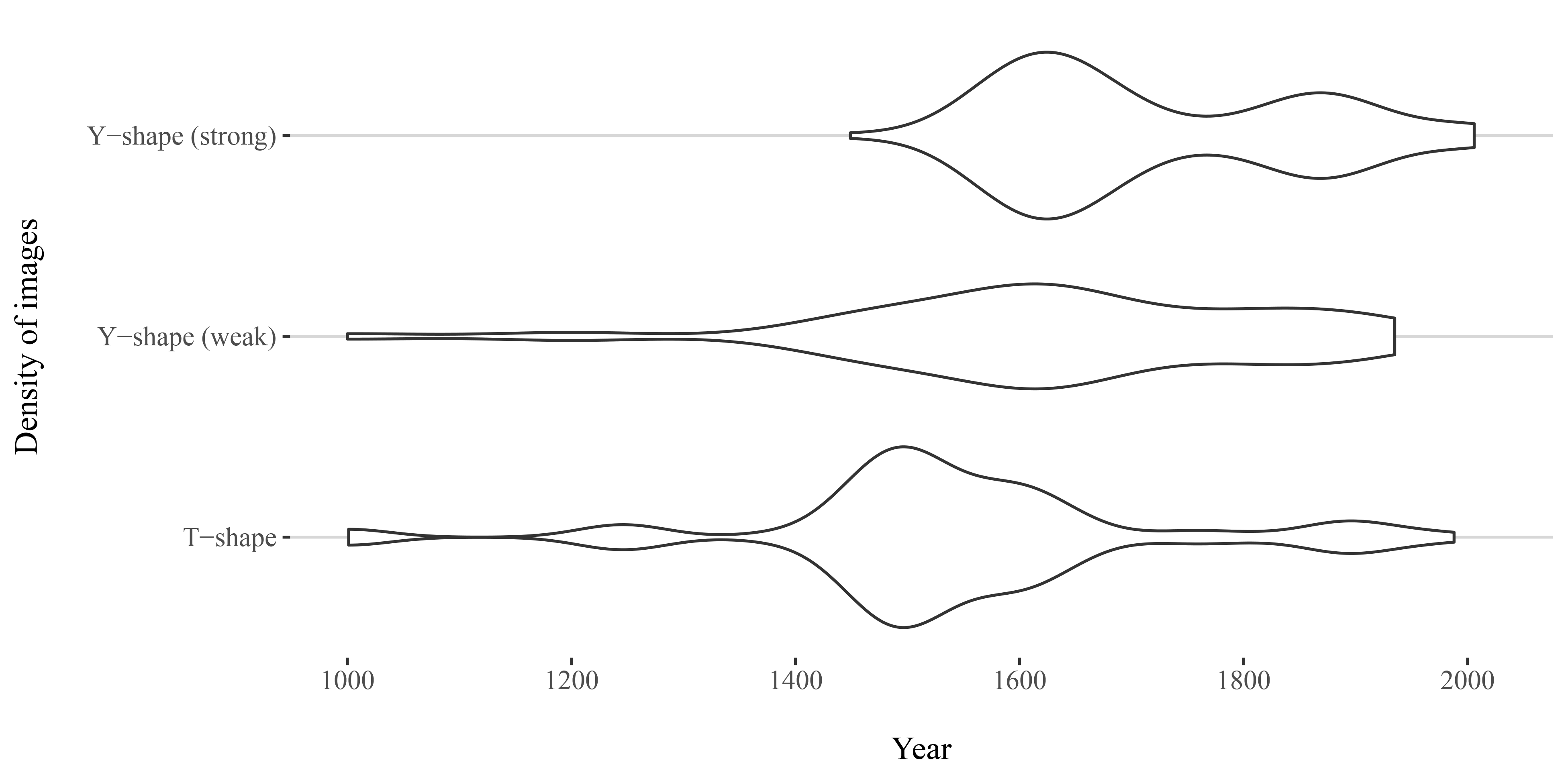

To understand the evolution of iconographies in art history — here: the

postural configurations in crucifixion scenes — it is essential to analyze

both the posture and its temporal distribution. This involves, in

crucifixion scenes, distinguishing between

T- and

Y-shaped upper-body postures that depend on the arms’

position on the cross. To assess the Pr-VIPE’s ability to differentiate

between such configurations, we first select three crucifixion depictions

from Wikidata: Marcello Venusti’s

Christ on the

Cross (1500–1625), in

T-shape, with arms

outstretched horizontally;

[14] Diego Velazquez’s

Christ

Crucified (1632), in weak

Y-shape, with

arms slightly upraised;

[15] and Peter Paul Rubens’

Christ Expiring on the Cross (1619), in strong

Y-shape, with arms strongly raised.

[16] That is, each image served as a query to

identify the top 100 similar Wikidata object entities based on their

upper-body similarity. Analysis of the bootstrapped distribution of creation

dates then shows that

T-shapes start increasing

around 1200, peak sharply around 1400, and then gradually decrease, with

another smaller peak around 1800, while

Y-shaped

figures have a more widespread, uniform distribution between 1400 and 1900 —

in case of weak

Y-shapes, without notable peaks

(Figure 8 in Appendix A). The evolution of the shapes can be also observed

clearly in the contour plot of the two-dimensional upper-body posture

embedding. Naturally,

T- or slightly

Y-shaped figures, with their symmetrically

outstretched arms, are most often associated with crucifixions, whereas the

upward curvature of stronger

Y-shapes appears in a

wider range of contexts, including depictions of ascension and resurrection

that imply spiritual elevation, such as the putti in Rembrandt’s

The Ascension (1636). This variation in upper-body

posture is also reflected in the artworks’ temporal distribution: Strong

Y-shapes occur mostly around 1600, with another

notable peak around 1900, and are rarely found before 1400. The Pr-VIPE’s

ability to distinguish these postures suggests its effectiveness in

identifying both the physical configurations and, on closer historical

inspection, the underlying symbolic meanings. This evidence suggests

potential verifiable patterns in the representation of different upper-body

forms across historical periods, although conclusive historical evidence

remains to be established.

6. Discussions

In contrast to previous approaches that compute how similar two postures are

based solely on the positions or angles of two-dimensional keypoints [

Kovar, Gleicher, and Pighin 2002] [

Pehlivan and Duygulu 2011], our three-step HPR

pipeline integrates the relational context between joint positions by encoding

them in 320-dimensional view-invariant embeddings. Qualitative experiments on a

data set of 644,155 Wikidata object entities confirm the method’s validity: They

reveal dense clusters in the two-dimensional embedding spaces corresponding to

the 110 manually selected reference postures derived from Iconclass. These

findings demonstrate the system’s ability to detect clusters of similar postures

in the context to their artistic expression. Although some inaccuracies — mainly

due to bounding box detection limitations — are observed, these errors in

individual joint estimates do not significantly affect retrieval performance. As

shown, at the aggregate level, certain posture configurations are identified as

compact hotspots that differ from other, more common postures in the Wikidata

within the embedding space. However, while it is possible to interpret the

embedding space from a historical perspective, the methodology at the aggregate

level, as opposed to the posture-to-posture search at the individual level,

differs markedly from traditional historical research, with the reliance on

metadata-induced density peaks being intuitive to statisticians, but highly

unconventional to art historians.

It is therefore of utmost importance to emphasize that HPR is designed to support

knowledge generation, rather than to directly ‘produce’ knowledge — as evidenced

by the

T- and

Y-shaped upper-body

configurations of the crucifixion scenes, which may spotlight historically

significant conjunctions. DL models can identify areas that may contain evidence

or knowledge, but these need to be validated, at least by random sampling;

without integrated close viewing, computational analysis cannot be taken as

conclusive evidence or knowledge unless DL models independently provide a

historically plausible interpretation of their results — a capability yet to be

achieved. They, at least currently, can serve only as

recommender

systems, provided they achieve high accuracy, as our research has

shown. Still, the utility of computational methods in humanities research should

not be underestimated: They allow researchers to quickly navigate and reduce

large data sets to tractable sizes, making possible studies that would otherwise

be logistically unfeasible due to the sheer volume of the data involved.

[17] To fully

realize the potential of these methods, we consider a hybrid approach that

combines traditional scholarly expertise with computational techniques to be

essential. Such integration could enrich the interpretive possibilities of

data-driven inquiries into the past and facilitate a more nuanced understanding

of cultural heritage, revealing previously overlooked or misinterpreted

connections between objects. Thus, while computational analysis is neither

infallible nor standalone, it does represent a significant advance in the

toolkit of humanities researchers, providing them with unprecedented analytical

capabilities — if they know how to utilize them.

However, whether a research question can be effectively pursued using DL methods

also depends heavily on the availability of the study’s objects, similar to

traditional humanities research where the identification and collection of

relevant sources, including archival material, is a crucial preliminary step. As

shown in Figure 5, Wikidata primarily features post-1800 artworks, with medieval

art notably underrepresented — a pattern that is common across databases. Since

the true distribution of artworks is not known definitively, reliance on

digitally available repositories might introduce research bias by either under-

or over-representing certain historical periods or artistic styles. At present,

and likely in the future, it is not possible to assemble a data set that

represents the full range of art history — or other historically oriented areas

of visual culture — as many objects have been lost or have not yet been

digitized. Nevertheless, for narrowly defined research questions, it may still

be possible to rely on a manually compiled and thoroughly curated data set, such

as one developed within a specific project. Despite the potential for

large-scale data sets like Wikidata to include works outside the traditional

canon, they may also inadvertently reinforce the canon within the digital

environment. It is therefore essential to critically evaluate the data sets

employed in digital humanities research, especially considering their potential

impact on the results: The skewed focus on more contemporary objects may cause

researchers to overlook or inadequately cover older or lesser-known historical

periods and styles, thereby perpetuating a biased view of art history.

Moreover, the performance of HPE, and by extension HPR, depends fundamentally on

the accuracy of the bounding box detection in the pipeline’s initial stage.

Incorrectly estimated bounding boxes will almost certainly lead to incorrectly

estimated — or even missing — keypoints, which in turn will affect, to a lesser

extent, the embeddings generated from these keypoints. Improving the accuracy of

bounding box detection could mitigate cascading errors in the pipeline, thereby

increasing the reliability of the entire process. As shown by [

Springstein et al. 2022], the solution may not lie in the adoption of progressively newer

models that yield little practical benefit. Instead, optimizing the training

data used to create these models might prove more effective — for instance, by

merging data sets like PoPArt [

Schneider and Vollmer 2023] and

SniffyArt [

Zinnen et al. 2023] to provide a broader range of

posture scenarios and thus enrich the model’s learning environment. However,

increasing model performance depends more on the quality of the data rather than

just its quantity. Investing in well-curated training data sets that feature a

diverse array of human figures, especially those previously underrepresented,

could significantly boost model training (cf., [

Zhao et al. 2024]). [

Springstein et al. 2022] confirm that data sets with thorough,

high-quality domain coverage outperform larger but less diverse alternatives.

Consequently, for studies requiring high visual specificity not represented in

available data sets, a small, manually annotated training data set is still

imperative for achieving high model performance.

It could be argued that relying on a single embedding space provides only a

partial understanding of the underlying structures in high-dimensional data. By

reducing the dimensionality of an originally practically inscrutable latent

space, one inevitably imposes certain modeling assumptions that may obscure or

distort inherent relationships. In addition, the specific parameters employed in

any given dimensionality reduction technique yield divergent visualizations of

the same data, i.e., not all apparent clusters in a two- or three-dimensional

projection necessarily exist in the original high-dimensional space, and points

that appear far apart in the embedded space may actually be close neighbors in

the latent space. However, [

Wang et al. 2021] observed empirically that certain

approaches can maintain more robust structures under parameter variation. Their

sensitivity analysis across multiple datasets — with both known local and global

structures — demonstrates that PaCMAP consistently preserves qualitative

relationships regardless of parameter choice. In the context of our case study,

this finding implies that the semantic positioning of similar postures remains

reproducible and is not merely a product of random chance or overly sensitive

parameters. This level of robustness contrasts with methods such as UMAP [

McInnes 2018], which are more sensitive to parameter

tuning. Ultimately, the decision to employ a particular dimensionality reduction

technique should be made in the context of the research scenario — the data’s

size and the nature of the structures one seeks to preserve — to ensure that any

conclusions drawn from a visual analysis are based on solid empirical ground

rather than the artifacts of a particular algorithm.

7. Conclusion

The analysis of posture has traditionally been marginalized in art-historical

scholarship, prompting the adoption of digital methodologies to re-examine it on

a large scale. In Section 3, we proposed a three-step methodology for this

purpose that leverages whole-body keypoints to differentiate the human body into

upper- and lower-body segments. These segments were first encoded in

320-dimensional Probabilistic View-invariant Pose Embeddings

(Pr-VIPEs). Using these Pr-VIPEs, we then assembled 110 reference postures for

classification purposes. This methodology’s relevance to art-historical research

was validated through qualitative experiments with a data set of

644,155 art-historical Wikidata objects, primarily addressing the following

questions:

How can the perceptual space of embeddings, obtained by Deep

Learning (DL) models, be explored and interpreted? What spatial

patterns emerge within these spaces, and to what extent can they encode

posture?

In this context, Section 4 outlined a two-stage approach of broad-scale filtering

preceded by a detailed examination of individual postures: a distant

viewing focused on an aggregate-level analysis of density-based

hotspots, and a close viewing focused on an individual-level

analysis of query postures. At the aggregate level, certain posture

configurations were identified as compact hotspots that differed from other,

more common postures within the embedding space. Yet, for postures that have

undergone considerable historical evolution, the effectiveness of

metadata-driven pre-filtering diminishes. Here, the individual-level

posture-to-posture search is advantageous because it provides

resilience to minor inaccuracies without significantly affecting the retrieval’s

performance. Moreover, the case study revealed numerous dense clusters in the

two-dimensional embedding spaces, largely corresponding to the reference

postures. It proved the system’s ability to identify hotspots and decipher

connections between object entities, thus expediting cluster identification in

the embedding space — DL models can thus serve effectively as recommender

systems. However, their application must be critically evaluated and

not undertaken without scholarly oversight, as misestimations could raise

concerns among traditional art historians about the trustworthiness of

computational methods. Nevertheless, we argue that even with manual

re-evaluation, the likelihood of encountering works outside the canon increases,

although the reproduction of the canon is, of course, also perpetuated in the

digital space.

In the future, we plan to refine our research pipeline, focusing in particular on

improving the classification process, which currently — due to the limited

number of reference postures — makes it difficult to achieve the granularity

required for complex art-historical inquiries. Although it was shown that the

integration of a reference set can largely align with existing taxonomies of

body-related behavior, it also highlighted the challenges of discriminating

among a large number of postures with high variability. We intend to adopt a

cross-modal retrieval framework, as introduced by [

Delmas et al. 2022], which

integrates two-dimensional keypoints with textual descriptions into a joint

embedding space. By synthesizing these methods into a unified pipeline, we are

for the first time able to trace the evolution of posture on a large scale,

allowing a thorough exploration of their psychic structures. This approach is

not limited to art-historical objects but also holds promise for cultural

heritage objects in a broader sense. For instance, in theatre studies, the

analysis of body postures and movements could facilitate comparative

examinations across different artistic traditions, periods, and conventions.

Appendix B

Scatter plots represent human postures as individual points, which are placed

according to their x and y

coordinates from the reduced two-dimensional embedding. In contrast to scatter

plots, two-dimensional histograms visualize the density of the underlying data

rather than individual points. They partition the embedding space into a fixed

number of bins, here 250, with each bin colored according to the number of

figure postures it contains. Similarly, contour plots visualize the density of

postures on a two-dimensional plane. Much like topographic maps, they connect

points of equal density with contour lines and label each contour with its

corresponding density level. Thus, while contour plots offer an abstract,

continuous representation of density gradients, two-dimensional histograms

provide a segmented, quantitative analysis. Areas of high density may indicate

frequently observed or ‘standard’ postures, whereas regions of low density may

be related to less common postures.

Works Cited

Arnold and Tilton 2019 Arnold, T. and Tilton, L.

(2019)

“Distant viewing. Analyzing large visual

corpora”,

Digital Scholarship in the

Humanities, (34), pp. i3–i16. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqz013.

Baxandall 1972 Baxandall, M. (1972) Painting and Experience in 15th Century Italy. A Primer in the

Social History of Pictorial Style. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Brandmair 2015 Brandmair, K. (2015) Kruzifixe und Kreuzigungsgruppen aus dem Bereich der

,,Donauschule”. Petersberg: Imhof.

Butterfield-Rosen_2021 Butterfield-Rosen, E. (2021) Modern Art and the Remaking

of Human Disposition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago

Press.

Carion et al. 2020 Carion, N., Massa, F.,

Synnaeve, G., Usunier, N., Kirillov, A., and Zagoruyko S. (2020)

“End-to-end object detection with transformers”, in

Computer Vision – ECCV 2020. Cham: Springer

(Lecture Notes in Computer Science), pp. 213–229. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58452-8_13.

Chen and Guestrin 2016 Chen, T. and Guestrin, C.

(2016)

“XGBoost. A scalable tree boosting system”, in

B. Krishnapuram et al. (eds.)

Proceedings of the 22nd ACM

SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data

Mining. New York: ACM, pp. 785–794. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785.

Delmas et al. 2022 Delmas, G., Weinzaepfel, P.,

Lucas, T., Moreno-Noguer, F., and Rogez, G. (2022)

“PoseScript. 3D human poses from natural language”, in S. Avidan et

al. (eds.)

Computer Vision – ECCV 2022 – 17th European

Conference. Cham: Springer (Lecture Notes in Computer Science), pp.

346–362. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20068-7_20.

Egidi et al. 2000 Egidi, M., Schneider, O.,

Schöning, M., Schütze, I., and Torra-Mattenklott, C. (2000) “Riskante Gesten. Einführung”, in M. Egidi et al. (eds.) Gestik. Figuren des Körpers in Text und Bild, pp.

11–41. Tübingen: Narr (Literatur und Anthropologie, 8).

Elcott 2016 Elcott, N.M. (2016) Artificial Darkness. An Obscure History of Modern Art and

Media. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eriksson 1973 Eriksson, E.S. (1973)

“Distance perception and the ambiguity of visual stimulation. A

theoretical note”,

Perception &

Psychophysics, 13(3), pp. 379–381. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03205789.

Gombrich 1966 Gombrich, E.H. (1966)

“Ritualized gesture and expression in art”, in

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of

London. (B, Biological Sciences), pp. 393–401. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1966.0025.

Harada et al. 2004 Harada, T., Taoka, S., Mori,

T., and Sato, T. (2004)

“Quantitative evaluation method for

pose and motion similarity based on human perception”, in

4th IEEE/RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots,

Humanoids 2004. New York: IEEE, pp. 494–512. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICHR.2004.1442140.

Haussherr 1971 Haussherr, R. (1971) Michelangelos Kruzifixus für Vittoria Colonna. Bemerkungen zu

Ikonographie und theologischer Deutung. Opladen: Westdeutscher

Verlag.

Impett and Süsstrunk 2016 Impett, L. and

Süsstrunk, S. (2016)

“Pose and pathosformel in Aby Warburg’s

Bilderatlas”, in G. Hua and H. Jégou (eds.)

Computer Vision – ECCV 2016 Workshops. Cham: Springer (Lecture

Notes in Computer Science), pp. 888–902. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46604-0_61.

Jenícek and Chum 2019 Jenícek,

T. and Chum, O. (2019)

“Linking art through human

poses”, in

International Conference on Document

Analysis and Recognition, ICDAR 2019. New York: IEEE, pp. 1338–1345.

Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.2019.00216.

Karjus et al. 2023 Karjus, A., Solà, M.C., Ohm,

T., Ahnert, S.E., and Schich, M. (2023)

“Compression

ensembles quantify aesthetic complexity and the evolution of visual

art”,

EPJ Data Science, 12(1). Available

at:

https://doi.org/10.1140/EPJDS/S13688-023-00397-3.

Kovar, Gleicher, and Pighin 2002 Kovar, L.,

Gleicher, M. and Pighin, F.H. (2002)

“Motion graphs”,

ACM Transactions on Graphics, 21(3), pp.

473–482. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1145/566654.566605.

Li et al. 2021 Li, K., Wang, S., Zhang, X., Xu, W.,

and Tu, Z. (2021)

“Pose recognition with cascade

transformers”, in

IEEE Conference on Computer

Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2021. New York: IEEE, pp.

1944–1953. Available at:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.06976.

Linderman et al. 2019 Linderman, G.C., Rachh,

M., Hoskins, J.G., Steinerberger, S., and Kluger, Y. (2019)

“Fast interpolation-based t-SNE for improved visualization of single-cell

RNA-seq data”,

Nature Methods, 16(3).

Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-018-0308-4.

Liu, J. et al. 2021 Liu, J., Shi, M., Chen, Q., Fu,

H., and Tai, C-L. (2021)

“Normalized human pose features for

human action video alignment”, in

IEEE/CVF

International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2021. IEEE, pp.

11501–11511. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.01132.

Liu, T. et al. 2022 Liu, T., Sun, J.J., Zhao, L.,

Zhao, J., Yuan, L., Wang, Y., Chen, C.-L., Schroff, F, and Adam, H. (2022)

“View-invariant, occlusion-robust probabilistic

embedding for human pose”,

International Journal

of Computer Vision, 130(1), pp. 111–135. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-021-01529-w.

Madhu et al. 2023 Madhu, P., Villar-Corrales, A.,

Kosti, R., Bendschus, T., Reinhardt, C., Bell, P., Maier, A., and Christlein, V.

(2023)

“Enhancing human pose estimation in ancient vase

paintings via perceptually-grounded style transfer learning”,

ACM Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 16(1),

pp. 1–17. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1145/3569089.

Madhu_2020 Madhu, P., Marquart, T., Kosti, R.,

Bell, P., Maier, A., and Christlein, V. (2020)

“Understanding compositional structures in art historical images using pose

and gaze priors. Towards scene understanding in digital art history”,

in A. Bartoli and A. Fusiello (eds.)

Computer Vision – ECCV

2020 Workshops. Cham: Springer (Lecture Notes in Computer Science),

pp. 109–125. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66096-3_9.

Malkov_2020 Malkov, Y.A. and Yashunin, D.A.

(2020)

“Efficient and robust approximate nearest neighbor

search using hierarchical navigable small world graphs,”

IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine

Intelligence, 42(4), pp. 824–836. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2889473.

McCarren 2003 McCarren, F.M.

(2003) Dancing Machines. Choreographies of the Age of

Mechanical Reproduction. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

McInnes 2018 McInnes, L.,

Healy, J., Saul, N., and Großberger, L. (2018)

“UMAP.

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection”,

Journal of Open Source Software, 3(29). Available at:

https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00861.

Merback 2001 Merback, M.B. (2001) The Thief, the Cross and the Wheel. Pain and the Spectacle of

Punishment in Medieval and Renaissance Europe. London: Reaktion

Books.

Offert and Bell 2023 Offert, F. and Bell, P.

(2023)

“imgs.ai. A deep visual search engine for digital art

history”, in A. Baillot et al. (eds.)

International Conference of the Alliance of Digital Humanities

Organizations, DH 2022. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8107778.

Pehlivan and Duygulu 2011 Pehlivan, S. and

Duygulu, P. (2011)

“A new pose-based representation for

recognizing actions from multiple cameras”,

Computer Vision and Image Understanding, 115(2), pp. 140–151.

Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cviu.2010.11.004.

Ren et al. 2020 Ren, X., Li, H., Huang, Z., and

Chen, Q. (2020)

“Self-supervised dance video synthesis

conditioned on music”, in C.W. Chen et al. (eds.)

MM ’20: The 28th ACM International Conference on

Multimedia. ACM, pp. 46–54. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1145/3394171.3413932.

Rhodin, Salzmann, and Fua 2018 Rhodin, H.,

Salzmann, M. and Fua, P. (2018)

“Unsupervised geometry-aware

representation for 3D human pose estimation”, in V. Ferrari et al.

(eds.)

Computer Vision – ECCV 2018 – 15th European

Conference. Springer (Lecture Notes in Computer Science), pp.

765–782. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01249-6_46.

Schneider and Vollmer 2023 Schneider, S. and

Vollmer, R. (2023)

“Poses of people in art. A data set for

human pose estimation in digital art history”. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2301.05124.

So and Baciu 2005 So, C.K.-F. and Baciu, G. (2005)

“Entropy-based motion extraction for motion capture

animation”,

Computer Animation and Virtual

Worlds, 16(3–4), pp. 225–235. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1002/cav.107.

Springstein et al. 2022 Springstein, M.,

Schneider, S., Alhaus, C., and Ewerth, R. (2022)

“Semi-supervised human pose estimation in art-historical images”, in

J. Magalhães et al. (eds.)

MM ’22: The 30th ACM

International Conference on Multimedia. ACM, pp. 1107–1116.

Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1145/3503161.3548371.

Steinberg 2018 Steinberg, L. (2018) Michelangelo’s Sculpture. Selected Essays. Edited by

S. Schwartz. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tikkanen 1912 Tikkanen, J.J. (1912) Die Beinstellungen in der Kunstgeschichte. Ein Beitrag zur

Geschichte der künstlerischen Motive. Helsingfors: Druckerei der

finnischen Litteraturgesellschaft.

Ufer et al. 2021 Ufer, N., Simon, M., Lang, S., and

Ommer, B. (2021)

“Large-scale interactive retrieval in art

collections using multi-style feature aggregation”,

PLOS ONE, 16(11), pp. 1–38. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259718.

Ullman 1979 Ullman, S. (1979)

“The interpretation of structure from motion”, in

Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. (B,

Biological Sciences), pp. 405–426. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1979.0006.

van de Waal 1973 van de

Waal, H. (1973) Iconclass. An Iconographic Classification

System. Completed and Edited by L. D. Couprie with R. H. Fuchs.

Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

van Straten 1994 van

Straten, R. (1994) Iconography, Indexing, Iconclass. A

Handbook. Leiden: Foleor.

Vaswani et al. 2017 Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N.,

Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A.N., Kaiser, L., and Polosukhin,

I. (2017)

“Attention is all you need”, in I. Guyon et

al. (eds.)

Advances in Neural Information Processing

Systems 30, Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems

2017, pp. 5998–6008. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762.

Wang et al. 2021 Wang, Y., Huang, H., Rudin, C.,

and Shaposhnik, Y. (2021)

“Understanding how dimension

reduction tools work. An empirical approach to deciphering t-SNE, UMAP,

TriMap, and PaCMAP for data visualization”,

Journal of Machine Learning Research, 22, p. 1–73. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2012.04456.

Warburg 1998 Warburg, A. (1998) “Dürer und die italienische Antike”, in H. Bredekamp and

M. Diers (eds.) Die Erneuerung der heidnischen Antike.

Kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge zur Geschichte der europäischen

Renaissance. Gesammelte Schriften. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, pp.

443–449.

Zhao, Salah, and Salah 2022 Zhao, S., Salah, A.A.

and Salah, A.A. (2022)

“Automatic analysis of human body

representations in western art”, in L. Karlinsky, T. Michaeli, and K.

Nishino (eds.)

Computer Vision – ECCV 2022

Workshops. Cham: Springer (Lecture Notes in Computer Science), pp.

282–297. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25056-9_19.

Zimmerman 2011 Zimmermann, M.F. (2011) “Die Sprache der Gesten und der Ursprung der menschlichen

Kommunikation. Bildwissenschaftliche Überlegungen im Ausgang von

Leonardo”, in H. Böttger, G. Gien, and T. Pittrof (eds.) Aufbrüche. Für Andreas Lob-Hüdepohl. Eichstätt:

Academic Press, pp. 178–197.

Zinnen et al. 2023 Zinnen, M., Hussian, A., Tran,

H., Madhu, P., Maier, A., and Christlein, V. (2023)

“SniffyArt. The dataset of smelling persons”, in V. Gouet-Brunet, R.

Kosti, and L. Weng (eds.)

Proceedings of the 5th Workshop

on analySis, Understanding and proMotion of heritAge Contents, SUMAC

2023. New York: ACM, pp. 49–58. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1145/3607542.3617357.