Abstract

As in other western cities, the fast-paced urban, industrial, and commercial sprawl

of Paris during the 19th century provided the backdrop and driving force for the

publishing phenomenon of trade directories. We show how these collections of millions

of nominative entries associated with addresses can be turned into a serial dataset

whose massive, fine-grained, and geolocated nature opens up new possibilities for

quantitative and multi-scale analyses of the dynamics at play during one of the most

dramatic socio-spatial transformations of the city. We highlight the methodological

conditions of such data-driven analyses and emphasize the importance of understanding

source effects. The findings underscore the significance of data science in

critically evaluating digital sources and adhering to best practices in the

production of large historical datasets.

1. Introduction

City directories are extensive lists of residents, shops, businesses, and

institutions, with a description of their professional or commercial activity and

an

address to locate them. They became a widespread publishing phenomenon in Europe and

the USA during the 19th century, subsequent to the introduction of house numbering

in

the 18th century [

Tantner 2009]

[

Rose-Redwood and Tantner 2012]

[

Albers and Kappner 2023]. The primary purpose of directories was to facilitate

business relations between people, whether through written correspondence or by

visiting the listed address. Published at a rapid pace (often annually) throughout

the 19th and 20th centuries, they form sequences of highly detailed snapshots of the

economic activities taking place in a city. They are a highly fine-grained source

of

information for interdisciplinary studies of cities, as well as for specialized

fields research such as urban studies and historical economics [

di Leonardo et al. 2019]

[

Bell et al. 2020]. Yet their potential for quantitative historical studies

is vastly under-exploited, due to the extensive transcription, geocoding and

structuring operations required to transform them into digital databases.

In the research project SoDUCo, we developed an automatic pipeline to extract,

semantically annotate, geocode, and structure 144 directories of Paris published

between 1787 and 1914. This process involved image segmentation to detect entries,

OCR for text extraction, named entity recognition and geocoding to assign geographic

positions to the addresses in directory entries, resulting in an open dataset of

about 23 million records [

GeoHistoricalData 2023].

The spatial and social dynamics of European cities in the 19th century are

characterized by growth, sprawl, and socio-economic transformations as a result of

industrialization. Growth and sprawl dynamics have been mainly investigated using

demographic sources, dependent on census rationale and administrative boundaries,

or

getting morphological information from city plans. Both types of sources are less

detailed than directories in terms of spatial and temporal scale.

For the first time, it is possible to study the dynamics of a European capital at

a

key moment in its history, with unprecedented spatio-temporal resolution and extent:

address-level information for the whole city, roughly every year over more than a

century. Adopting a data-driven geography perspective, we demonstrate that the Paris

directories dataset is a valuable multi-scale and multi-granularity (spatial and

temporal) research tool for analyzing the city’s urban growth throughout the 19th

century. However, such a massive digital dataset can mask many biases and source

effects. We show that an expert examination of the directories, and their extracted

and geocoded content, helps to better understand the dynamics at work in the city’s

urbanizing margins.

Paris changed a lot between 1787 and 1914. Demographic growth is considerable, rising

from an estimated 593k inhabitants in 1780 to around 2.9M in 1911 [

Brée 2020]

[

Varet-Vitu, Marraud, and Mermet 2020], partly combined with strong urban sprawl. Major

planning policies have led to significant transformations in the urban fabric that

affected the organization of the city, house numbering and street naming. Haussmann’s

renovation (1853-1870) dramatically reshaped entire parts of the city, while the

merging of all neighboring municipalities following the 1859 law on the extension

of

Paris, abruptly doubled the city administrative area in 1860 [

Jordan 1995]

[

Montel 2012]. Until then, the municipal territory was bounded by the

Fermiers généraux wall

[1]

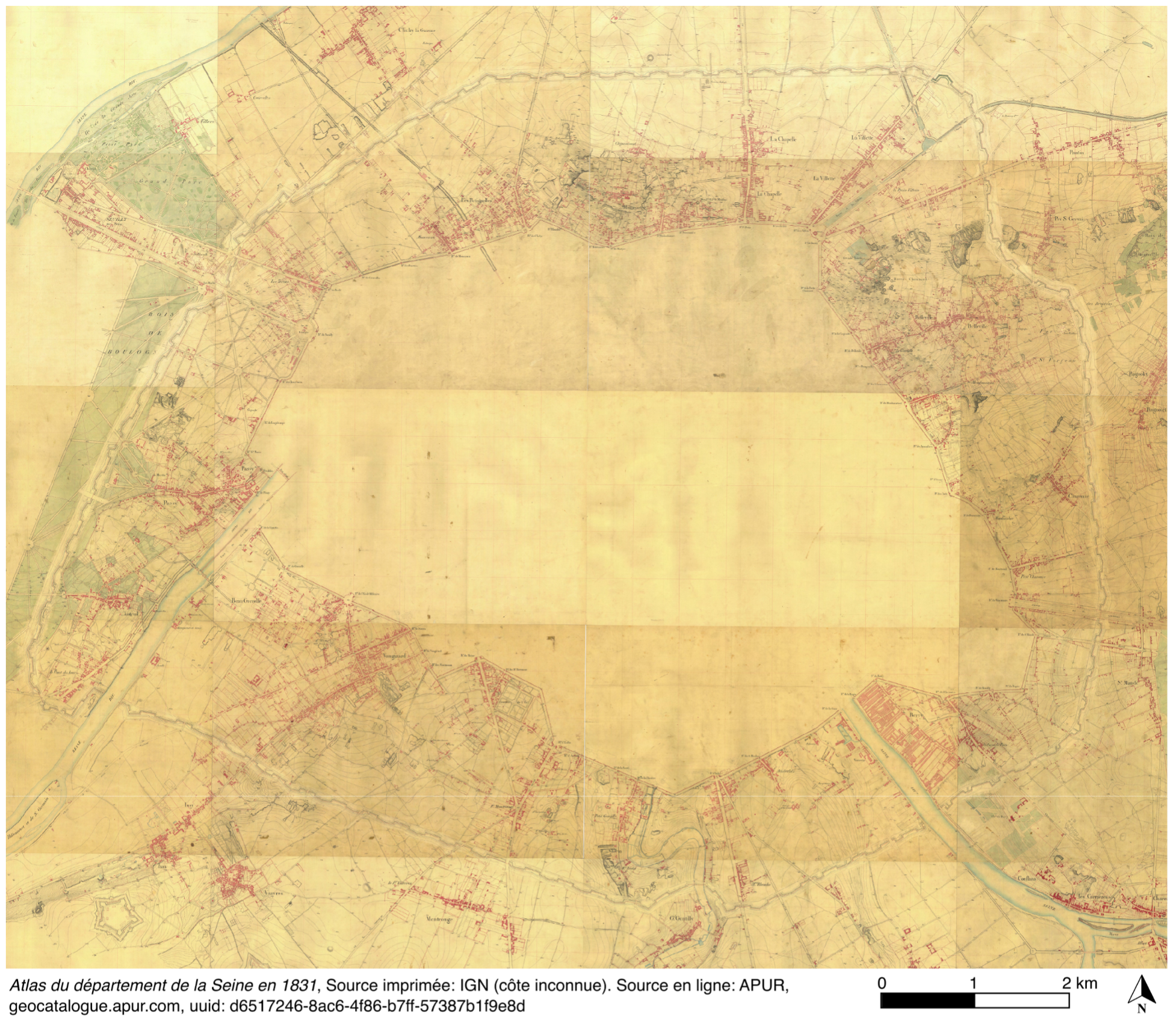

(Figure 1, delineation of the blank area). The division of Paris into districts and

arrondissements was completely revised when the administrative area was extended to

the Thiers wall in 1860. Built between 1841 and 1844, this fortified belt is already

planned on the map of Figure 1 dating from 1831. The red-lavished built-up areas

already stretch along the main roads that connect the city to the surrounding

networks beyond its administrative boundaries.

The study of urban fabric depends on the ability to map directory entries in

geographic space on the basis of the addresses they contain. This operation, known

as

geocoding, is essential and requires precise knowledge of the evolution of the urban

fabric of Paris, in particular the numbering of buildings and houses.

The introduction of systematic house numbering in European and American cities during

the 18th century reflected the emergence of a regulatory and rationalist vision of

municipal administrations in their territories [

Rose-Redwood and Tantner 2012].

The first

[2] systematic numbering of all buildings in Paris was attempted by the

revolutionary administration in 1790, only to be replaced in 1805 by a numbering

based on a standardized set of rules still in place today. Although the system

stabilized from 1805 onward, Paris’ growth and densification caused frequent changes

in the numbering, throughout the 19th century. Despite this instability, it is

notable that residents quickly adopt the numbering system as a way of locating

themselves in the city [

Denis 2015].

Our paper is structured into five sections. We begin with a literature review on

geocoding strategies in historical spaces, with a focus on Paris (Section 2). We then

present the directories editors’ conception of the city of Paris and the corpus

constituted to study the dynamics of the Parisian urban fabric (Section 3). In the

following methodological section, we explain how we apprehend the urban fabric

through density analysis of distinct geolocated address points in directories

(Section 4). We demonstrate that these address points serve as a reliable proxy of

the Parisian urban fabric, allowing us to analyze urban sprawl, de-densification of

the center, and local densification trajectories between 1822 and 1914 through a

data-driven geographic approach (Section 5). Finally, we discuss the challenges of

capturing urban margins and the choices made in transcribing and enriching Paris

directories, highlighting best practices and emphasizing the role of data science

in

critically assessing this large digital source (Section 6).

2. Literature review: Geocoding addresses in historical spaces

If directory entries can be systematically located in urban space through addresses,

enabling spatial and spatio-temporal analysis, it is necessary to translate the

addresses into precise geographical coordinates — in short, to geocode them.

Geocoding, whether automated or manual, is a standard data preparation step in

quantitative social sciences that focus on the spatial dimension of phenomena.

However, it can introduce significant bias in spatial analysis [

Zandbergen 2009] and presents a methodological challenge for fields

relying on statistical methods and large-scale, fine-grained data, particularly at

the individual level, such as health research and historical demography [

Delmelle et al. 2022]. A notable example is the study of [

Hedefalk et al. 2018], analyzing how geocoding strategies affect spatial

analyses of the relationships between population density, proximity to wetlands, and

mortality rates in Swedish parishes (1850–1914). Their study shows a significant

underestimation of mortality and a weakening of statistical significance when the

granularity of the geodata supporting the geocoding is coarser than that of the

demographic data recorded at parcel level.

While in many geohistorical studies geocoding is done manually, e.g. using GIS

software, here we focus on its automation using software tools called “geocoders”, which are the only reasonable option for handling

large datasets. Geocoders are search engines capable of returning the geographic

coordinates of a place from a textual reference to that place, such as a postal

address, based on a reference geospatial database. Geocoding historical data presents

its own challenges, as it often requires a database adapted to the period and region

under study. There are three general strategies for historical geocoding, depending

on the level of detail required, the scale of analysis, and the availability of

geospatial data sources.

One strategy involves either the direct use of contemporary on-the-shelf geocoding

services such as Nominatim or ArcGIS [

Pearce et al. 2018], or the development

of geocoding tools that leverage contemporary gazetteers and knowledge bases like

Geonames or DBPedia [

Åhlfeldt, Berman, and Wick 2016]. This is well suited to small

datasets where the time gap between the historical data and the geocoder reference

database is reduced. However, an extensive step of manual inspection and correction

is often required to ensure consistent and reliable results, as the lack of

synchronicity between the geocoder and the queries can lead to a high false positive

rate. Some proposals incorporate heuristics to reduce uncertainty and errors, e.g.

by

reducing the search area considered for each query [

Daras, Feng, and Dibben 2015].

A second strategy is to build custom geocoders for historical data which combine

multiple gazetteers, either loosely coupled [

Mertel et al. 2021] or fully

integrated in a single database [

Cura et al. 2018]. Efforts are concentrated

on creating a historical reference database for the geocoder, extracting data in

historical sources like maps, or integrating existing historical geodatasets. The

goal is to create a geocoding process that fits the case study to achieve better

consistency while still being able to deal with large scale and fine-grained data.

The main drawback being the cost of building the reference data, but these approaches

tend to favor open data pooling and crowdsourcing to build large historical

gazetteers [

Grossner and Mostern 2021].

The third hybrid strategy aims to get the best of both worlds by coupling large,

up-to-date geographic databases with specialized historical gazetteers. For example,

to locate historical census addresses from 1901 in England and Wales, [

Lan and Longley 2019] use a lower granularity historical gazetteer as a fallback to

geocoding on the Ordnance Survey address database

The dramatic instability of Paris address numbers over the 19th century precludes

anachronistic geospatial references as a geocoding support and calls for the use of

address geodatabases contemporary with the directories (see Appendix 8.1).

3. Dataset: The alphabetical address lists of Parisian directories

Challenges arise with the Parisian directories corpus due to its construction from

sources spanning over a long time period. Changes in political, technical,

economical, and social contexts affect how companies edit directory collections and

display their content. As a result, the internal organization of directories evolves

over time, as does their social coverage. We present the corpus compiled for this

paper (3.1.) and then show that editors had conceived Parisian space in terms of

socio-economic functioning (3.2.).

3.1. Compilation of the study corpus

We did a systematic chronological inventory of the directories of Paris between

1780 and 1914 during the SoDUCo project [

Baciocchi and Cristofoli 2022]

[

Cristofoli and Baciocci 2024]. Building on the seminal work of Jeanne Pronteau

(1966) and the French National Library catalog, we identified 341 books, organized

into 57 series, which are grouped into 24 collections [

Pronteau 1966]. We created a detailed inventory containing information on the content,

structure, and quality of digitization

[3] of the 166 copies that have been digitized and openly published.

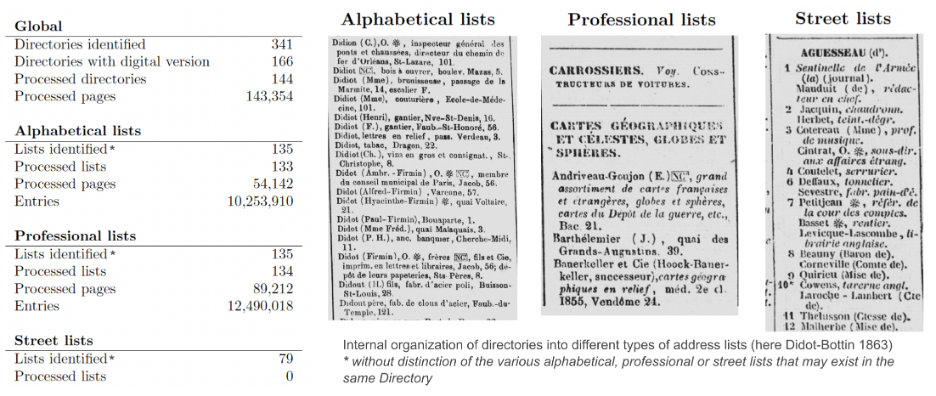

Directory address lists typically follow three formats: alphabetical, by

profession, and by street (see Figure 2) to facilitate searching for readers of

the time. Paris directories list a wide variety of individuals: diverse merchants,

craftsmen, manufacturers, doctors, midwifes, lawyers, bankers, owners, annuitants,

etc. The lists and their content, however, changed over time. Until the late

1810s, alphabetical lists included prominent inhabitants, while professional lists

featured merchants. After that, alphabetical lists began to combine both

categories. From 1903 onward, the editors of the Didot-Bottin moved prominent

residents into a separate directory entitled

Bottin mondain

[

Firmin-Didot and Firmin-Didot 1903].

We selected directories approximately five years to study urban sprawl and

densification. We assume this temporal resolution to be precise enough to capture

city-scale dynamics while keeping the dataset to a reasonable size. The selection

of specific years is however a compromise between methodological choices and

practical constraints, such as digitization quality or our desire to study a

common collection of directories, since they are more comparable with each other

than directories from different collections (see Appendix 8.2).

3.2. Parisian space as conceived by editors: A functional definition of the

city

Editors never explain their conception of Paris and its limits. As an example, the

prospectus for the directory published by Bottin in 1820 describes the

organization of the book as follows:

“The Almanach du Commerce

presents three main divisions: 1° Paris; 2° French departments and colonies; 3°

foreign countries. The first division, Paris, alone occupies two-fifths of the

volume, and begins with lists of the capital’s merchants”

[

Bottin 1820, prospectus, our translation]. In a lengthy

paragraph, Sébastien Bottin explains the major changes he has made to the

nomenclatures of the lists and the cross-referencing systems, compared with the

lists published by Jean de La Tynna two years earlier, but he is silent on his

conception of the delimitation of Paris.

The presence of individuals located outside the Fermiers

généraux wall before 1860 reveals the editors’ conception of Paris.

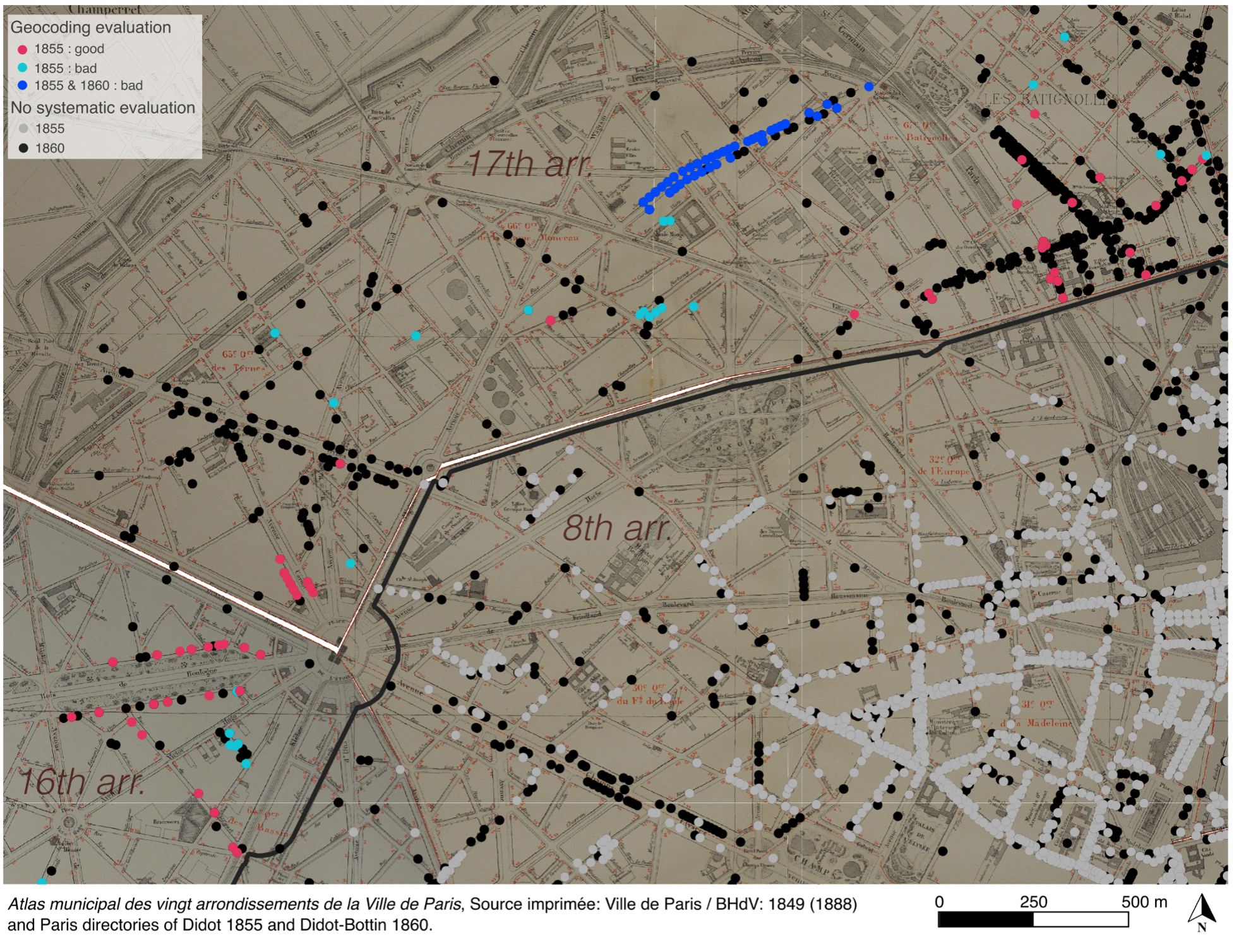

Figure 3 represents geolocated addresses in western Paris in 1855 and 1860. The

space of the directories covers part of the urbanization front, outside the area

delimited by the Fermiers généraux wall (red dots

in 1855 on Figure 3). In this sense, editors did not conceive Paris in terms of

its administrative and fiscal boundaries, but in terms of its socio-economic

functioning. The important issue was to connect individuals in the city and from

the city with others who were part of wider networks by establishing lists, and

including, if necessary, individuals who lived or performed their activities

outside the Fermiers généraux limits but belonged to

socio-economic networks of Paris.

4. Methodology: density analysis of geolocated addresses points

4.1. Distinct geolocated directory addresses points

A single directory entry may contain several addresses, and the same address may

be found in many directory entries. For instance, when an entry contains a

separate manufacturing and sales location or, conversely, when the same

manufacturing location houses several manufacturers. As a result, the geocoding

process of entries locates all occurrences of the same address at the same

coordinates, resulting in many duplicated address points (see Appendix 8.3.1 for

an extended example).

Since the study focuses on the evolution of the urban fabric using directories,

rather than the distribution of individuals in the city, we consider only unique

occurrences of geocoded addresses within each directory. To achieve this, we group

overlapping geocoded address points into a single point, retaining only distinct

addresses from each directory. These “distinct geolocated directory addresses

points” are referred as “geolocated addresses” in the following text

and figures for the sake of simplicity.

4.2. Point density analysis

Our study relies on Miller and Goodchild’s (2015) conception of data-driven

geography. The large volume of spatial and

“messy”

[

Miller and Goodchild 2015, p. 2] socio-spatial data produced in the SoDUCo

project provides an opportunity for a heuristic knowledge discovery approach:

Starting from the hypothesis that geolocated addresses may correlate with the

urban sprawl and densification of Paris, we explore the various aspects of the

data that may bear witness to this dynamic.

We prioritize geovisualizations to facilitate data exploration and understanding.

Our focus is on the evolution of the density of geolocated addresses over time and

at the city scale, deliberately setting aside the analysis of point patterns. We

chose not to delve on spatial patterns in the local configurations of all

geolocated address points as they are deeply tied to urban structures such as the

street network, which has already been extensively analyzed for Paris during the

19th century [

Barthelemy et al. 2013].

Additionally, we opt for a discrete representation of densities rather than

estimating continuous spatial distributions, e.g. through kernel smoothing. First,

the results of these techniques may be less well understood from an interpretative

point of view. Indeed, regular tessellation

“suggest the use

of an estimation process [...] in contrast, smooth contour lines give little

clue to this underlying estimation step”

[

Carr, Olsen, and White 1992, p. 231]. Secondly, as noted by [

Evangelista and Beskow 2018], social spatio-temporal phenomena are typically

discrete information; in our case, they exist only where addresses are present.

Spatial smoothing techniques are likely to spread information in areas where there

are no buildings and addresses, generating cartographic artifacts which impair

visual understanding of the phenomenon. The edges of the city, which are a focal

point of our study, would be significantly affected as data points are scarce in

those areas.

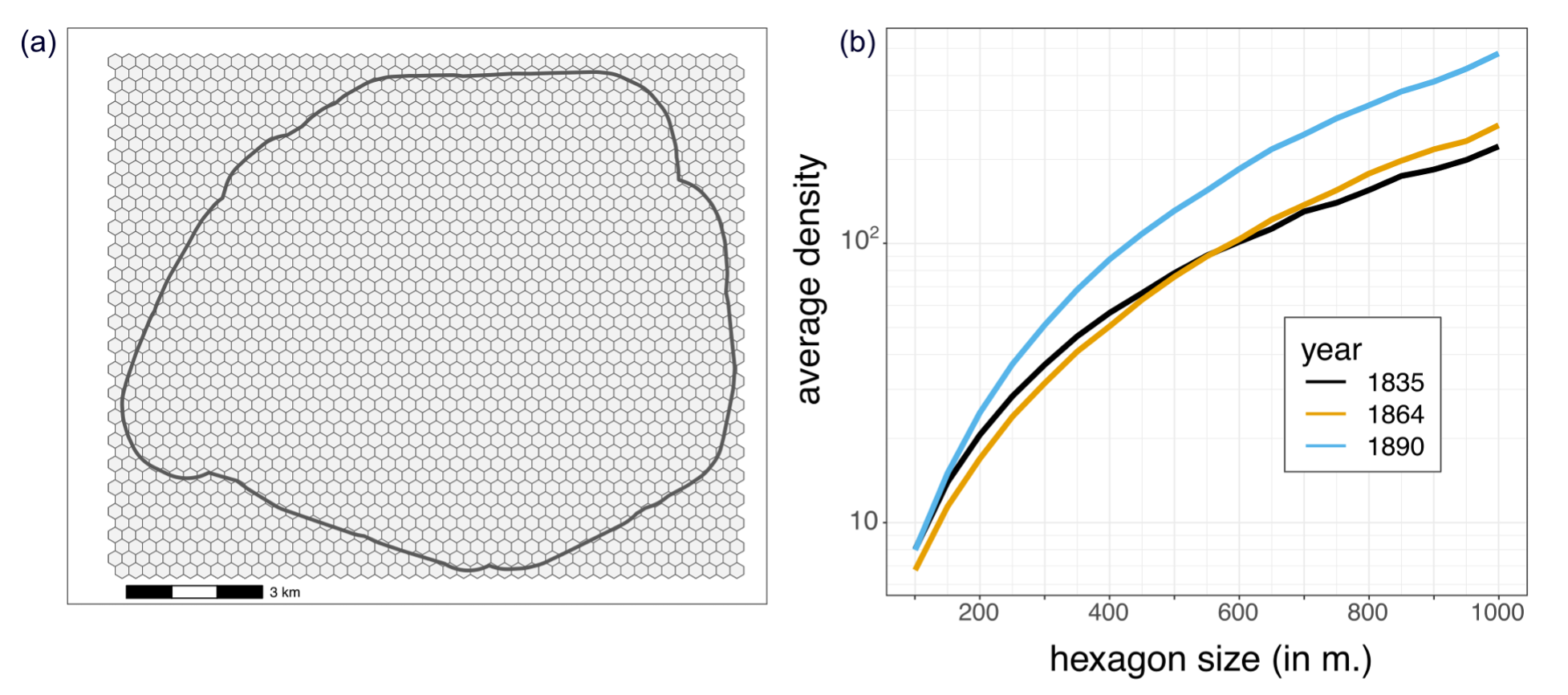

In order to have a stable framework for studying the evolution of geolocated

addresses, we create a hexagonal grid covering the maximal extent of Paris over

the 19th century, then bin geolocated addresses points in cells at each time step

to produce a series of 2D histograms whose cells are immediately comparable [

Carr, Olsen, and White 1992]. The advantage of a hexagonal grid over a more commonly

used square grid is that the nearest neighbors in a hexagonal grid are

symmetrical. Indeed, the barycenters of neighboring hexagons are equidistant,

unlike those of a square grid, where diagonal neighbors have greater distances

than neighbors of the four cardinal directions. As Peuquet noted,

“radial symmetry makes this model advantageous for radial search

and retrieval functions,”

[

Peuquet 1984, p. 85] making it especially useful for

analyzing intra-urban density, given the center-periphery structure of this

spatial phenomenon.

The drawbacks of this method are the same as those of the quadrats

[4]: It is

not sensitive to the relative position of the addresses within the cells, and the

densities created are sensitive to the resolution of the grid. The first

limitation is irrelevant in our case as we are not interested in exploring point

patterns. However, the second limitation is important because the aggregation of a

points pattern into area-based surfaces is always sensitive to the size of the

spatial entities [

Openshaw 1983]. The larger they are, the weaker

the spatial differentiation/concentration. In order to choose an appropriate grid

resolution, we proceeded iteratively by testing several cell sizes from 100 to

1,000 m (Figure 4, a). The average density of geolocated addresses across

different hexagon sizes at three different dates reveals continuous growth (Figure

4, b). Consequently, there is no particular hexagon size that should be

prioritized to measure urban density. Instead, the selection of one hexagon size

over another must be made qualitatively. After several iterations of size

parameter explorations, we settled on a threshold of 400 m, which appears to be a

good compromise. On the one hand, the grid remains quite fine, as a 400 m hexagon

represents a very small central district of Paris. On the other hand, it is wide

enough to ensure cartographic legibility.

5. Urban sprawl and density of Paris (1822-1914)

The data obtained from the digital transcription and enrichment of directories

changes the analytical framework: 1) in terms of precision, with very fine spatial

(address-level) and temporal (quasi-annual) resolutions; 2) in terms of scope, as

the

entire spatial and temporal evolution of the city can be apprehended over a century.

In this section, we show how these changes enable us to build up a global panorama

of

socio-spatial dynamics of Paris. We examine the urban space drawn by the directories

and the gazetteer used in the geocoder (5.1). We then present a synthetic overview

of

the urban sprawl and de-densification of central Paris between 1822 and 1914 (5.2).

Finally, we show how the data-driven approach reveals differentiated urban dynamics

(in space and time), providing the basis for new hypotheses and further research

(5.3).

5.1. The “numbered” space of Paris: The urban fabric transcribed through

directories and through the gazetteer

We approximate the “numbered” space of Paris through the concave hulls

calculated from the address points of two atlases of the gazetteer. The resulting

areas are shown to scale in black in Figure 5, together with the administrative

boundaries of the city (in white) and the total mapped area (in gray). Both

atlases are working and communication tools of the Municipality, showing the

surroundings of the city for illustration purposes, and do not indicate any

numbers in these zones. Within the city, the space covered by numbers does not

cover the whole administrative area. The difference is noticeable between 1836 and

1888. At that date, only the outskirts of the fortifications are unnumbered, while

address points are rare in a wide band around the 1836 boundaries. These areas are

shown as built-up on the maps, but they are made up of large urban blocks that are

often devoid of information, suggesting that urbanization is still very partial,

or at least poorly recorded by the urban administration.

Comparing address points extracted from the atlases with geolocated addresses of

directories allows cross-analysis of the areas covered by these two kinds of

sources. We focus on (1) the subsets of distinct addresses in the gazetteer for

the two atlases

[5], and (2) the distinct

geolocated addresses in the 1835 and 1890 directories. The sets of points in the

gazetteer and the directories can be compared by looking at their relative spatial

distribution (Figure 6). Each sub-figure (a, b, c, d) plots the ratio \( ρ_g/ρ_d\)

of the density of

geolocated addresses in a directory \(d\) (top line: the 1835 directory, bottom 1890)

with those in one

of the atlases \(g\) of Paris

(left: the Jacoubet 1836 atlas, right: the Municipal 1888 atlas). Values less than

1 indicate that the directory contains more geolocated addresses than the

gazetteer. This is possible because the geocoder prioritizes sources close to the

query date but can also retrieve results from a more temporally distant

cartographic source (see Appendix 8.1). For example, if an address from the 1835

directory is not found in the Jacoubet source, it may be geocoded using data from

the 1888 Municipal atlas. To help the reader, the main figures are accompanied by

the density maps of the geolocated addresses of the directory and the atlas

compared.

Views (a) and (d) in Figure 6 show that the ratio between each directory and its

closest atlas in time is close to 1. In addition, over 98.5 % of the distinct

addresses in the 1835 and 1890 directories are geolocated (see Appendix 8.3.2).

The directories therefore are fairly representative of the density of the numbered

buildings, with less accuracy for the recently urbanized edges.

A subset of addresses from the 1835 directory have been geocoded using the 1888

atlas, as shown in (b). However, there are very few of these directory addresses

compared with those of the atlas in 1888 (see density maps to the right in (b)).

Conversely in (c), the 1890 directory shows that the margins of Paris before 1860

are now largely present in the directory and are anchored in an area that is

probably much denser than in 1836 (green hexagons). The opposite dynamic can be

seen in the extreme center of the city. Indeed, there are fewer geolocated

addresses in the 1890 directory than in the Jacoubet atlas (c), and more addresses

in the 1835 directory than in the Municipal atlas (b).

5.2. Urban sprawl and city center de-densification (1822-1914)

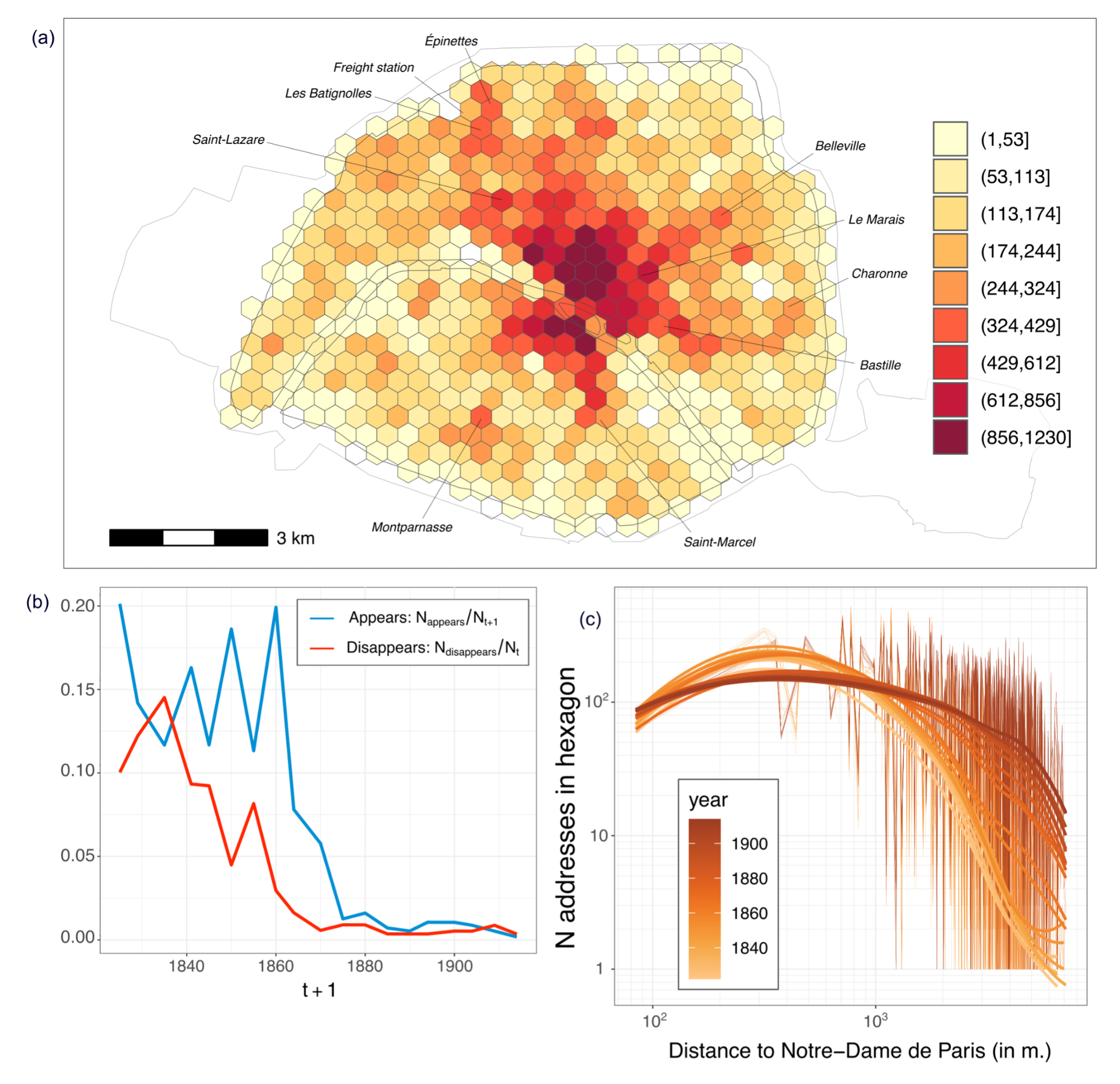

Figure 7 (a) reveals a panorama of the density of Paris through the cartography of

all geolocated addresses. The space is particularly dense in the vicinity of La

Cité and Saint-Louis Islands. On the right bank of the Seine (to the north), the

very high density is mainly included within the former boundary of the enclosure

of Charles V. On the left bank of the Seine (to the south), the densest areas are

those formerly included in the wall of Philippe Auguste, particularly in the Odéon

neighborhood and the Latin Quarter.

The center-periphery gradient of urban density is also clearly visible from La

Cité. On the left bank, the gradient runs southeast along Mouffetard street to the

Saint-Marcel faubourg. From the Odéon neighborhood, the gradient is noticeable to

the west, along Saint-Germain boulevard. On the right bank, the center-periphery

gradient is sharper to the east of the dense zone than to the north and west. From

the dense center, the gradient runs eastwards from the Saint-Paul neighborhood

through Bastille to Saint-Antoine, along Faubourg Saint-Antoine street, and then

northwards to Charonne. A gradient is also noticeable from the Marais to

Belleville. In the years 1820–1850, these central-eastern areas were the most

densely concentrated in terms of workshops and factories. Although the

industrialization of Paris led to the establishment of large industrial

establishments from the 1850s onward all around the

Fermiers généraux walls (much less in the west), the collective

manufactures remained concentrated in the center-east until the end of the century

[

Larroque and Jigaudon 1980]

[

Cottereau 1997]

[

Gribaudi 2014].

Lastly, we identify areas of density located in the vicinity of railway stations:

towards the Montparnasse station (south), in the vicinity of Saint-Lazare

(center-west), and in Batignolles and Épinettes neighborhoods (north-west), near

the Chemins de Fer de l’Ouest freight station.

The sub-figures (b) and (c) in Figure 7 illustrate the overall dynamics of

geolocated addresses. Sub-figure (b) shows the frequency of hexagons appearance

and disappearance. A hexagon appears when it contains geolocated addresses at time

\(t+1\) while being empty at

time \(t\) (and vice-versa for a

disappearance). New areas covered by directories were quite numerous until 1860,

with hexagon appearances representing between 12 and 20% of them (shown in (b)).

However, the variation from one date to the next reveals some noise during the

geocoding in areas outside the municipal boundary before 1860 (see discussion in

Section 6.1). Thereafter, appearances become less numerous, although new areas

continue to be occupied up to the mid-1870s. Meanwhile, less dense and more

peripheral areas also undergo erasure movements until the early 1840s, with

between 10 and 15% of hexagons disappearing

[6]. This trend persisted until 1870, albeit with a significant

reduction.

The center-periphery gradient persists throughout the study period (see Figure 7,

(c)), but it gradually diminishes over time. For instance, until 1855, the density

ranges from around 200 to 300 geolocated addresses per hexagon within

approximately 1 km of Notre-Dame cathedral, sharply declining beyond 2 km to

approximately 1 to 50 geolocated addresses per hexagon. Similar patterns are

observed until 1864, with slightly denser hexagons beyond 2 km from Notre-Dame.

Then, from 1870 to 1914, central areas experienced a slight decrease in density,

with hexagons within 1 km of Notre-Dame consisting of approximately 200 geolocated

addresses, while peripheral areas beyond 2 km became much denser. However, density

variations between hexagons remain significant, as evidenced by the notable

fluctuations of the thin lines in (c).

5.3. A century of the dynamics of urban density

We explore the overall picture in greater depth over time and space, in order to

identify the dynamics of urban density more precisely. To this end, we plot the

slope of the number of geolocated addresses per hexagon, normalized in space by

period in Figure 8. This representation provides two main spatial and temporal

reading levels. The first level refers to the whole city for a given period, and

the second to a specific segment of the city over several periods. In the

following subsections, we develop these two reading levels through case

studies.

5.3.1. The high society neighborhoods of Paris in the early 20th century

revealed through a source effect

Given that hexagons are growing on average for each period, negative values

generally represent lower relative growths than hexagons with positive values

in Figure 8. As an example in the initial period (1822–1825), there is a trend

of greater relative growth of geolocated addresses in the city center compared

to the periphery, indicating a notable center-periphery gradient.

Some periods may be marked by general decline. This is particularly true of the

years 1900–1904, where the average slope is -0.222. The positive values of the

hexagons thus reflect a lower relative decline than those of the negative

values (in strong decline). The decline in the number of geolocated

addresses

[7]

is fairly widespread throughout Paris, although some areas are still

growing

[8]: south-west, north around

Montmartre and the Nord and Est railway stations, and east in the 12th and 20th

arrondissements.

The general decline in 1900–1904 reflects editorial choices made by the company

that published directories during this period. Indeed, starting from 1903, the

editors of the Didot-Bottin initiated the creation of a separate directory

dedicated to prominent individuals, titled the

Bottin mondain

[

Firmin-Didot and Firmin-Didot 1903]. This new edition led to the exclusion of

individuals from the Didot-Bottin general directory studied here. The excluded

entries are varied, notably individuals designated as owners or annuitants, but

also deputies, ministers, or advisors at the Court of Cassation. Other

categories such as bankers, placement agents, and doctors remained in the

general directory. Thus, these people were not considered to belong to this

social echelon by the editors of the time, and/or they were deemed

indispensable to the list of actors in the socio-economic life of Paris,

appearing in both lists (the specific

Bottin

mondain list and the general list).

The socio-spatial divide of Paris from west to east is well-known during the

20th century, notably thanks to historical studies of the

Bottin mondain conducted by Cyril Grange [

Grange 1993]. However, the gradient of the social division of

Parisian space at the turn of the 20th century is clearly identifiable on the

1900-1904 map in Figure 8. The gradient is not entirely linear. It includes a

hyper-concentration (dark green hexagons on map) of prominent inhabitants in

the 8th arrondissement (south of Parc Monceau) and the 16th arrondissement

(Chaillot neighborhood). On the other hand, a continuum of affluent

neighborhoods is apparent in the city’s center-north (9th arrondissement),

center-southwest (in the 7th arrondissement between Saint-Germain and the

Invalides), and in the center near the Saint-Louis Island. Other areas are also

noteworthy, in particular the Petit Montrouge district in the south of Paris in

the 14th arrondissement. Indeed, the south of the district is wealthy (see

Appendix 8.4), whereas the concentration of affluent families is almost

invisible on the scale of the districts of Paris studied by [

Grange 1993]. This is likely due to the fact that his study is

based on a sample of 4,500 addresses from the

Bottin

mondain between 1903 and 1987, i.e. a sampled view of one social group

(that of the

Bottin mondain),

whereas the present study is based on all the addresses of the directories,

i.e. an exhaustive view of a set of social groups (of the directories).

5.3.2. Dynamics of densification of the 16th arrondissement and the southern

17th arrondissement

Figure 8 lets us analyze the density trajectory of a city segment over time.

The data-driven approach offers two main advantages: 1) We do not predetermine

the study area a priori, e.g. by selecting districts or arrondissements; 2) the

dynamics of the area under study are examined in relation to the urban space as

a whole.

In the 1850s and 1860s, the west of Paris underwent significant street

development, leading to the emergence of new neighborhoods and increased urban

density in these areas. Indeed, while only 9.3% of Haussmann’s construction

expenditure was associated with the newly annexed area beyond the

Fermiers généraux, most of the work was carried out in

western Paris, with the development of the Place de l’Étoile and the

Champs-Élysées, for example [

Faure 2004]. Street development is

well-documented in cartographic sources [

Andriveau-Goujon 1868]

and particularly significant in the 16th arrondissement and the south of the

17th arrondissement, south of the railroad lines leading to the freight station

near Batignolles and the Saint-Lazare station (see Figure 3). However, the rate

and extent of the densification of this area are unknown.

This area has been entirely covered by hexagons since the mid-1850s (in

particular beyond the Fermiers généraux wall,

see Figure 8). Geolocated addresses show overall positive slopes from that

point until 1900, but the normalized slopes per period shown in Figure 8 only

exhibit consistently positive trends from the mid-1880s in the 16th

arrondissement (with the exception of the years 1864–1870). On the other hand,

they show positive trends from the mid-1850s onward for the southern part of

the 17th arrondissement (except for the period 1880–1885). Consequently,

compared to other parts of Paris that experienced densification during the

second half of the 19th century, the intensity of densification in the southern

part of the 17th arrondissement was significant enough by 1855–1860 to be

notable on a citywide scale. However, it was not until another three decades

later that densification in the 16th arrondissement became apparent, coinciding

with a period of deceleration in densification across the city.

Several factors contribute to understanding this difference in the pace of

densification in Paris. Firstly, large industrial establishments were set up

mainly in the north and east of Paris between 1850 and 1870. This partly

accompanied the urban growth and densification shown in Figure 8. Subsequently,

Haussmann’s work in central Paris involved the construction of new streets and

the reorganization of city blocks to accommodate new buildings. To achieve

this, the administration’s authority to expropriate property was extended in

1852. Between the end of that year and 1859, 2,236 houses were demolished by

expropriation in Paris, according to Haussmann himself. As a result, over time,

some of the city’s inhabitants migrated to more peripheral areas — notably to

the east — all the more so as rents of older constructions raised dramatically

in the 1850s (by over 50%). Lastly, the newly built-up areas of the north of

the 16th and south of 17th arrondissements are characterized by wide avenues

and a high concentration of Haussman-style buildings, which have a low built

density compared to other Parisian areas [

Larroque and Jigaudon 1980]

[

Faure 2004].

In addition, qualitative analysis of the geocoding quality of directory entries

in the years 1855–1860 reinforces the identification of the local trajectories

of the south of the 17th arrondissement. Figure 3 shows geocoding problems in

the western edge of the city. In 1855, some entries were incorrectly geocoded,

as in Jouffroy street, south of the railroad lines. All the addresses in the

directory refer to the “Passage Jouffroy,” opened in

1845 and located in Montmartre. The densification dynamic between 1845 and 1850

observed by the two pink hexagons in Figure 8 is thus a geocoding bias. On the

other hand, the problem of distinguishing between the Jouffroy passageway and

street during geocoding is the same for the years 1855 and 1860. Consequently,

the calculation of space-normalized slope for this period — and subsequent

periods — is not altered by this geocoding bias, and the growth of the southern

17th arrondissement since 1855–1860 is historically dynamic.

6. Discussion

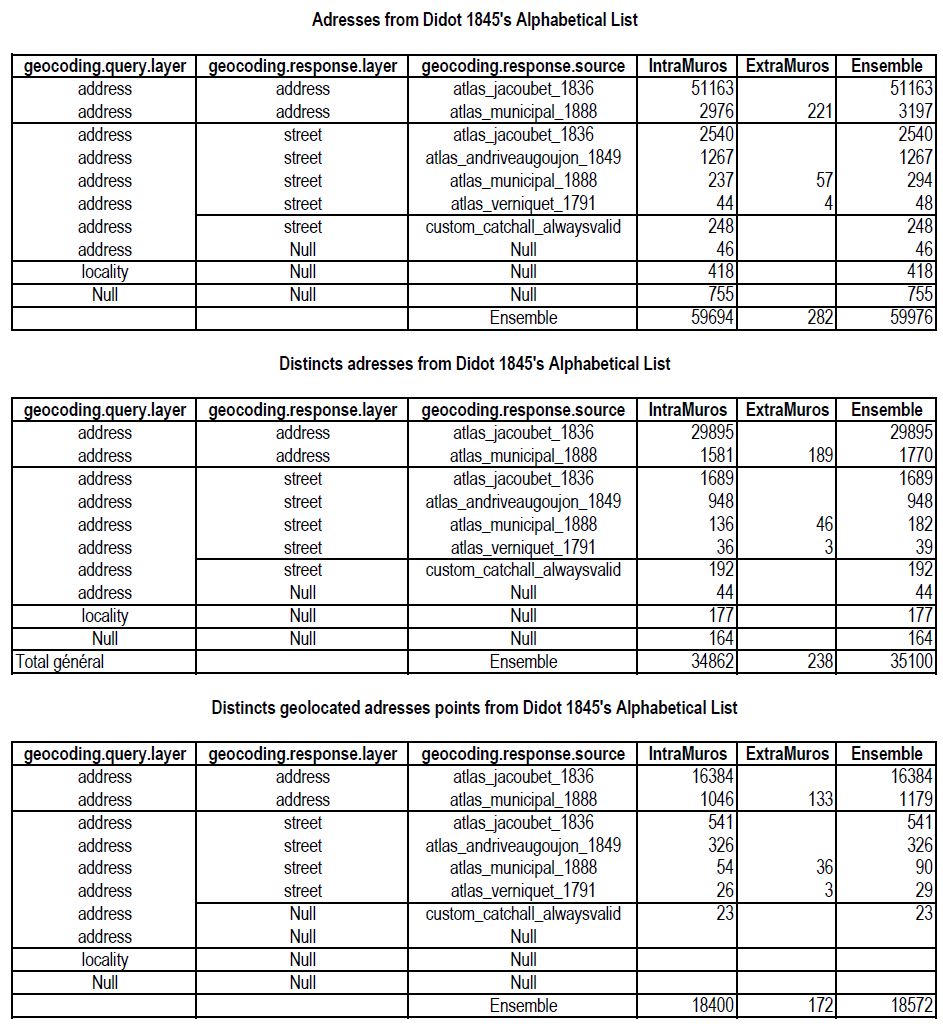

First, a qualitative assessment of the geocoding results for the 1845 directory

enables us to elaborate on the challenge of accurately apprehending urban margins

prior to the 1860 extension of Paris (6.1). We then examine the increasingly pressing

issue of how data produced by third parties can be appropriated and properly reused

in historical sciences, especially with the recent surge in open digital data from

archival sources. This challenge is particularly significant when large volumes of

digital data are generated through automated extraction and enrichment processes.

We

discuss two main questions: How and under what conditions can such digital sources

be

used effectively? (6.2) How can we understand them, assess their quality and their

relationship with the original sources? (6.3)

6.1. The difficulties of precisely capturing the edges of the city before

1860

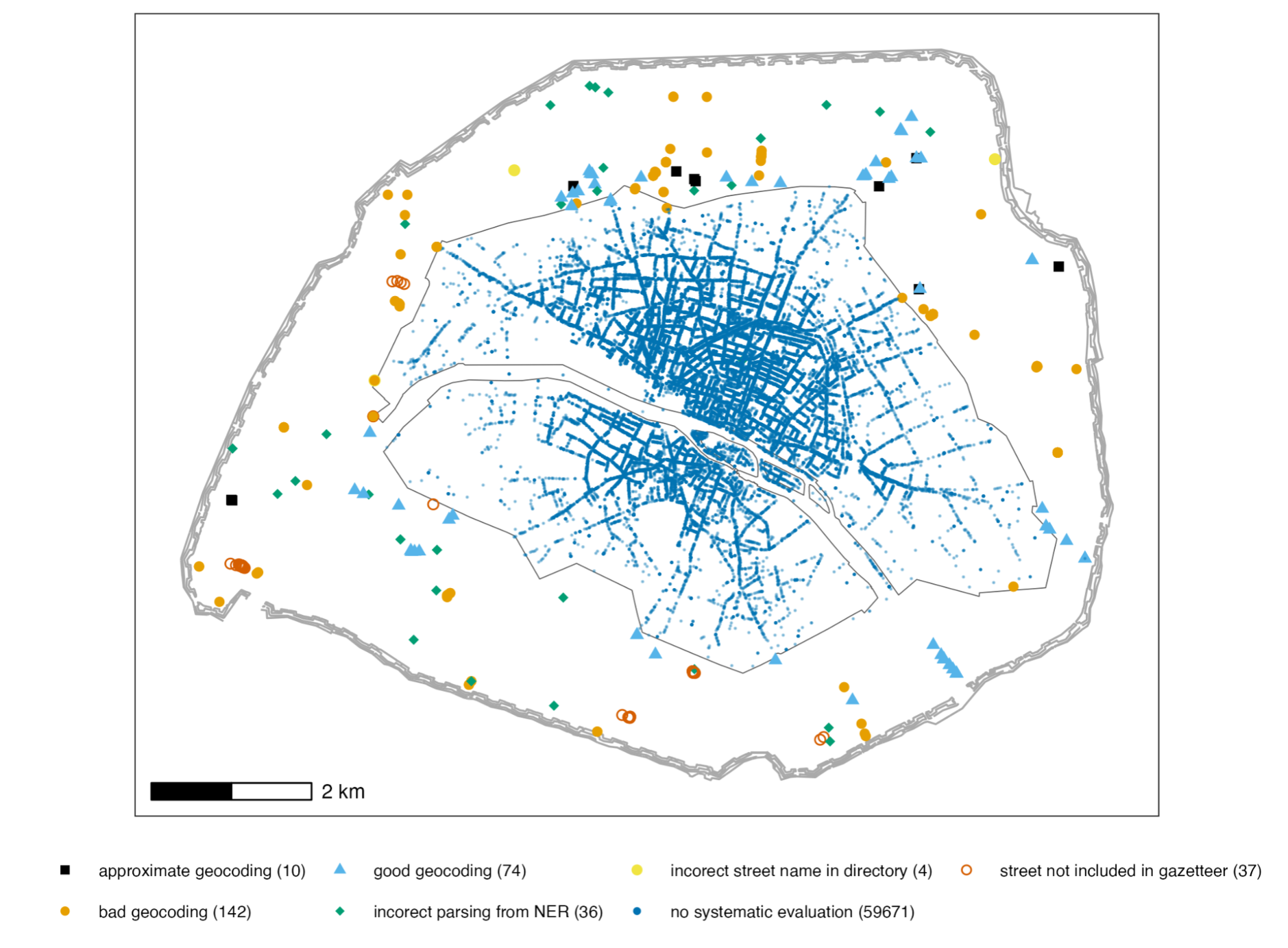

Examining the geocoding outcome and metadata of a specific directory enables a

qualitative and critical assessment of the process. We concentrate the evaluation

on the 1845 Didot directory because it was edited after the completion of the

Thiers wall, which created a new singular interface between the old and new

enclosure [

Firmin-Didot and Firmin-Didot 1845].

The table in Appendix 8.3.3 presents geocoding statistics for the 1845 directory,

organized according to the granularity level at which a match was found in the

gazetteer (at street or address-point). 94.6% of the geolocated addresses of the

directory are address-point. Looking at the contribution of the gazetteer’s

sources of the geocoder, 88.2% of them match with the 1836 Jacoubet atlas. These

high proportions of matching from the 1845 directory and 1836 gazetteer reveal

that the majority of addresses are located within the administrative limits of

Paris. The residual set of extra-muros geolocated addresses is very low: Only 172

are located outside of the Fermiers généraux wall

(0.009%).

A detailed study of these specific geolocations reveals that only 40% are correct

(see the map in Appendix 8.3.3). They are mainly concentrated in the business

neighborhoods of Bercy and near Ivry station, as well as in a few places around

Grenelle-Vaugirard and Vincennes. In the north, they are concentrated in a few

streets in the neighboring municipalities of La Villette, Montmartre and

Batignolles-Monceaux. However, these last two municipalities have expanded since

the 1820s [

Frondizi 2018]. These front lines of extramural

activities are confirmed by the systematic manual examination of the 123 addresses

in the alphabetical list and interpreted by the geocoder as

“localities” (see

the table in Appendix 8.3.3).

To sum up, the alphabetical list of 1845 partially records activities in the inner

suburbs. A focus on these peculiar spaces would require leveraging complementary

sources, in particular the Départements section

of the Didot directory, which includes a short list of the main shopkeepers in

each municipality. It is a possible perspective because the SoDUCo pipeline chain

can be applied to new and similar sources.

The case of the 1845 directory highlights the need for a critical analysis of the

edges of Paris up to the 1860s–1870s. In other words, the identification of

spatial patterns, as in the case of the 17th arrondissement study (see Section

5.3.2), requires to be confirmed by an in-depth qualitative analysis of the

geolocated addresses at the level of each directory entry, in order to discuss

what belongs to geocoding bias or to historical spatial dynamics.

6.2. Conditions for re-appropriating digital and enriched data of Paris

directories

Four main choices had been made in the SoDUCo project to encourage the

re-appropriation of Paris directories data.

The first is to consider very general named entity classes during the data

enrichment processes, specifically during the Named Entity Recognition (NER)

stage, in the content of a directory entry. Residents, shops, businesses and

institutions are all labeled as

“persons,” descriptions of their professional

or commercial activities fall into a single class named

“activity,” and their

addresses are made up of

“location” (i.e. street name) and

“cardinal”

(street number) entities [

Abadie et al. 2022]. The classes of recognized

entities are deliberately very broad in order to facilitate querying and

recombination of information. The objective is not to reconstruct — and therefore

impose — categorizations

[9] that

would be considered useful a priori, by grouping institutions on one side and

physical individuals on the other, for example, while the boundary is absolutely

non-obvious historically and in the original sources. Moreover, enriching

directory entries by geolocation is useful for different uses of the sources, and

physical space is a shared and semantically neutral referential. However, the

geocoding process is not neutral either because it relies on specific cartographic

sources. We thus integrate all information relating to geocoding queries,

responses and internal geocoding quality metrics into the final data at the scale

of each address of the entries of directories.

The massive, fine-grained data created by an automated pipeline makes it possible

to construct a specific data corpus a posteriori. It is then easier to build

different, evolving sub-corpora as research questions evolve. In practice, two

choices in data enrichment are crucial: 1) to preserve the link with the initial

source at the level of each directory entry, notably by referring to the digitized

source at page level; 2) to contextualize directory entries, i.e. to link each

entry to the type of directory list (alphabetical, by profession, by street), to

the directory itself, its year of publication and its belonging to a

collection.

Re-appropriating data also involves developing differentiated and meaningful

accesses to data for different types of users. Indeed, the ways in which

information is sought from sources and how data is manipulated vary from one

audience to another. Four ways of accessing Paris directories data have thus been

developed (see Appendix 8.5). They also are complementary. For example, it is

useful to access the IIIF viewer at the same time as the datasets when studying

specific entries in a neighborhood.

Finally, the original corpus created during the SoDUCo project mobilizes

heterogeneous sources (maps and plans) from numerous heritage institutions and

archive centers. It is implemented in the form of a geocatalog [

Hersent et al. 2023], which makes it possible to bring together sources,

treatments and tools, intermediate results and various datasets produced

[10]. The choice is to keep track and opening the processing and intermediate

data used to build the accessible Parisian directories data

[11]. The directory extraction and data enrichment processing chains are bricks

on which others can rely to better understand the construction of the data

delivered, and from which other corpora can be created by reusing them.

6.3. A back-and-forth process between pipeline extraction, data analyses and

original sources

The critical historical assessment of the data follows a constant back-and-forth

process between the pipeline chain, data analysis, and the original source. The

methodology is therefore progressive, which is why we have chosen to produce

successive versions of the data in the SoDUCo project, with evaluation and

feedback to adjust the pipeline chain.

This critical assessment is based on manual evaluations and on global metrics on

the dataset. For example, the study of the statistical distribution of the number

of entries per page in the alphabetical lists of each of the directories, which

are theoretically constant because these lists and their entries are particularly

systematized in their form and length (see Figure 2) let us identifying that the

image segmentation process was problematic for the directories of the years

1802–1828. The pipeline chain was transformed to take account of this problem, and

the evaluation of the following version of the data using this metric shows a very

significant improvement

[12]. The metrics need to be intellectually created in interdisciplinary

collaboration between

“modellers” and

“thematicians”[13] — in this case here between

computer scientists on the one hand, and historians and geographers on the other —

to be meaningful in terms of data usage and thematic questions. The conditions for

interdisciplinary work need to be put in place, in particular with modellers who

are receptive to thematic issues and thematicians who are technically capable of

constructing metrics to assess the quality of these data.

The process of going back and forth finally makes it possible to qualify,

criticize, and understand the source of the directories. This is the case, for

example, in Section 3.2, where we show how the geolocation of entries ultimately

provides a better understanding of editors’ conception of Paris. Although the

directories of Paris have been used historically to study particular categories of

economic agents, such as art merchants [

de Maupeou and Saint-Raymond 2013], or ways of

socializing, as in the case of the study of the particular

Bottin mondain

[

Grange 1996], this source was still largely unknown before their

digital transcription and enrichment for the long period of 1787-1914.

Transforming material into data requires an effort to understand it, to qualify

its own biases, its internal logic and its relationship with the society that

produced it.

7. Conclusion

The data acquired through the digital transcription and enrichment of directories

enable the investigation of urban fabric at unprecedented scales. Following a

data-driven approach we shed light on the extent of urban sprawl and de-densification

of the city center, never before quantified over such a long period (1822-1914) and

with such spatial and temporal precision across the entire city of Paris.

Three main thematic findings stand out from our study.

The de-densification of Paris was studied on a city-wide scale based on historical

demographics — e.g. through analysis of de-populating dynamics [

Bonvalet and Tugault 1984] — or based on morphology, but on a micro-level such as

building blocks [

Gribaudi 2009]. We show that the de-densification of

the built-up hyper-center is notable on an urban scale from the 1870s onward, i.e.

twenty years after the start of the large-scale works led by Haussmann.

We identify the pace and relative magnitude of urban sprawl and densification on the

edges of Paris. We show that data-driven geography is a relevant framework for

studying the spatial trajectories of specific urban areas.

Finally, we show that massive data cannot substitute for source effects. But when

the

latter are correctly identified, they reveal new historical findings, as in the case

of affluent Parisian districts observed in the early 20th century and the non-linear

west-east gradient of Paris, which features concentrations of affluent individuals

in

small and specific neighborhoods, as we shown in the case of the Petit Montrouge

district in the 14th arrondissement. In this case, we demonstrated that results from

data-driven approaches enable defining new places of investigations, from a social

and spatial micro-history perspective [

Gribaudi 2014]

[

Frondizi 2018]. In other words, our methodology links the often

far-independent approaches of micro-history and large-scale studies.

8. Appendix

8.1. Integrating the evolution of cities and address systems in an automated

geocoding process

8.1.1. Parisian gazetteer from four maps and atlases (1784-1888)

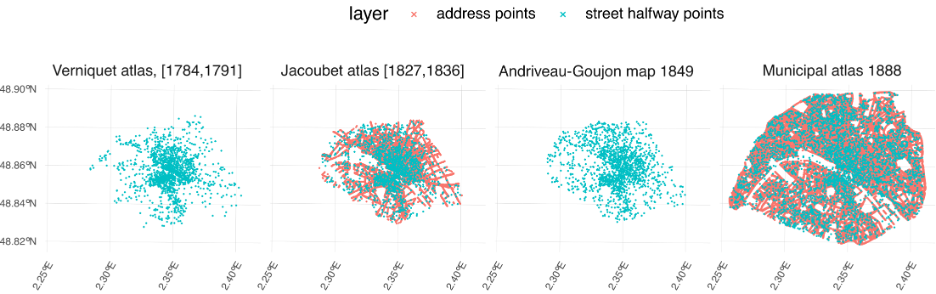

Large-scale city maps are one of the most valuable detailed topographic sources

for building cartographic representations of past urban landscapes. Once

georeferenced, they act as a geographical proxy, locating entities such as

streets, buildings, and addresses on the surface of the Earth. In order to

leverage historical maps as a geocoding basis for the city directories, we

gathered a gazetteer of address points and streets created within previous

digitization initiatives.

The resulting gazetteer contains around 136,500 geographic entities digitized

from four maps and atlases of Paris (Figure 9). 94% are address points with

their number and street name; the remaining 6% are named streets, approximated

by their halfway point. Each geographic entity is anchored temporally by a time

interval corresponding to the survey period of the source map, or to the

publishing date if the survey period is unknown. Thus, the information of the

gazetteer is time-dependent. Figure 9 represents the gazetteer and its entities

clustered in time according to the production periods of the four maps and

atlases. Each depicts Paris at different phases of its morphological evolution:

on the eve of the Revolution for the Verniquet atlas, in the 1830s after the

phase of national property subdivision for the Jacoubet atlas, before the

Second French Empire for the Andriveau-Goujon map, and after the major

Haussmanian transformations for the Municipal atlas.

The atlases focus on the area within the administrative boundaries of Paris,

i.e. within the Fermiers généraux limits

before 1860, and Thiers wall after that date. However, numbering inside the

administrative limits is only partial. In the Jacoubet atlas for example, the

zone between the boulevards and the Fermiers

généraux wall is mostly urbanized, yet address points are very

sparse. We are faced here with the discrepancies of these cartographic sources,

which combine multiple, heterogeneous administrative sources, possibly

partially out of sync with the exact historic reality of urbanization. In

addition, the suburbs of Paris prior to 1860 are not included in the current

state of the gazetteer.

8.1.2. Geocoding operation

All addresses identified in the directory entries are automatically geocoded.

For this purpose, the open-source geocoding software Pelias

[14] has been adapted to make it time-sensitive. The geocoder is built

around the ElasticSearch indexing and search engine

[15]. It is an adaptation of [

Cura et al. 2018] for ElasticSearch to

improve the performance and accuracy of the process. We refer to this paper for

the methodological and technical details on spatio-temporal geocoding.

A “spatio-temporal” geocoding query consists of the name of the address to

be located, a geographical level (street or address point) and a target date.

The geocoder searches for potential candidates within the gazetteer and orders

them by combining the similarity of their address name with the query and a

time distance value between the query date and the temporality assigned to the

gazetteer entity.

8.2. Building a research sub-corpus of address lists from specific

directories

8.2.1. Five commercial periods of Parisian directories

Parisian directories are commercial editions, involving competition between

publishers, buy-outs over time and moments of editorial monopoly. We revealed

five main periods thanks to the inventory of directories [

Baciocchi and Cristofoli 2022]. The years 1780–1793 are those of the origins. It

was followed by the emergence of the

Almanach du commerce (1798–1815). Competition was fierce, and

publications abounded until 1856, when the Firmin-Didot brothers bought the

Bottin publishing company. Thereafter, the period 1857–1890 was characterized

by the hegemony of the Didot-Bottin collection, before a new period of

competition began in 1891 and lasted until 1914.

The number of copies produced by editors grew through time. It shows how

directories were received and the importance of the enterprise: La Tynna

published 4,500 copies in 1816; Bottin 9,000 in 1840; Firmin-Didot brothers

18,000 in 1857, and 45,000 in 1878. The latter wrote in their 1857

introduction:

“to judge the importance of such a

publication by a single material fact, one need only say that, for the

eighteen thousand copies printed, almost all of which are sold with binding,

it is necessary, because of the size of the volume, for a flock of several

thousand sheep to provide their hides each year for this bookbinding”

[

Firmin-Didot and Firmin-Didot 1857, p. 8, our translation].

8.2.2. Selection criteria of alphabetical lists in directories

At the beginning of the 19th century, alphabetical lists included prominent

inhabitants, while professional lists featured merchants. In 1817, editor La

Tynna alphabetically listed merchants but maintained a separate alphabetical

address list for each population. Consequently, the alphabetical lists used for

the study are not comparable in terms of social coverage before and after the

end of the 1810s. We could incorporate the professional lists spanning from

1787 to 1816 in our sub-corpus to extend the temporal scope of the study.

However, we have recently extracted the data for these lists and have chosen to

focus solely on the alphabetical lists, of which we have a more comprehensive

understanding.

The publisher Bottin merged both alphabetical lists (merchants and prominent

inhabitants). We wish to begin the study period in 1820, one year after

Bottin’s first publication and the first year for which we have a digitized

version. However, at that date, the alphabetical list of merchants in the

Bottin directory contained a system of cross-references to the pages of the

list by profession. During the NER phase, page references were identified as

street numbers, generating noise during the geocoding phase. Consequently, we

have decided to start the study period in 1822, when Bottin’s cross-referencing

system was no longer in use.

8.2.3. Selection criteria of peculiar years

High-quality digital versions of directories are not consistently available.

For instance, the year 1830 lacks a suitable digital version, prompting us to

select the 1829 Bottin directory instead [

Cristofoli and Baciocci 2024].

Additionally, we wish to study identical collections over time whenever

possible, as their content is more uniform compared to different series and

collections. For example, we have access to the Didot-Bottin collection from

1860 onward and we have chosen the year 1909 instead of 1910. Indeed, there is

no high-quality digital version for the 1910 Didot-Bottin directory, whereas

one is available for 1909 and yet a processed version of the 1910

Paris-Hachette directory.

8.3. Evaluation of the geocoding

8.3.1. From initial data to distinct addresses and distinct geolocated

addresses points: an example

A list of ten directory entries in “rue

Sainte-Croix-de-la-Bretonnerie” (Figure 10, top table and map,

\(e = 10\)), selected from

the Didot 1845 directory, helps to explain the definitions used in the paper

and the following indicators.

The named entity recognition (NER) processing shows that these 10 entries

contain 8 addresses (\(a =

8\)), defined as character strings combining address.name and address.number. Indeed, the

address of “Rousselle, pharmac. en chef au

Val-de-Grâce” does not exist in the original source and a NER

detection problem had truncated the original entry “George,

bonneterie et nouveautés, Rochechouart, 10 [4]”. An address is

geolocated if the geocoding process is able to match the character string of

the address with the gazetteer (i.e. when geocoding.has_geocoding is true). In this example, 7 addresses are

geolocated with the Jacoubet atlas (\(ga

= 7\)), and “Baril-lerie, 7” was not

found in the gazetteer.

The “distinct addresses” of a directory, shown in the second table in

Figure 10, refer to all the unique character strings tagged as addresses by the

NER (\(da = 6\)). Two strings

that are close but slightly dissimilar are considered as different addresses

whenever a small variation appears, as in the case of “Ste-Croix-de-la-Bretonnerie, 54” and “Ste-Croix-Bretonnerie, 54”.

Finally, the distinct geolocated addresses refer to unique point geometries

associated with the directory entries (see section 4.1 for an extended

definition). Here, in the bottom table of Figure 10, 4 distinct geolocated

addresses had been found (\(dga =

4\)).

8.3.2. Overall evaluation

The evaluation of the geocoding process for each of the directories is

presented in Figure 11. Three main points stand out in the table.

Firstly, the ratio of the number of addresses per number of entries is always

greater than 1 (see \(a/e\) in

Figure 11), and mainly between 1.05 and 1.2, because individuals can have an

activity at several addresses. Two typical cases exist: On one hand, the

directory lists the place of manufacture and the place of sale of an

individual, or the various store units of an individual; on the other hand, a

store has two addresses because it is located at a crossroad and its storefront

faces two streets.

Secondly, the geocoding of addresses is systematically higher than 89.1% – as

shown with ratio \(ga/a\). On

average 95.7% of addresses are geocoded, varying from 89.1% to 98.2%.

Thirdly, the geocoding of distinct addresses is very good. Indeed, the ratio of

distinct geolocated addresses per distinct addresses is between 0.966 and 0.99

(see \(dga/da\) in Figure

11).

8.3.3. Evaluation of the geocoding in the edges of the city in 1845

There is no cartographic source of addresses in the gazetteer for areas outside

the Fermiers généraux wall before the 1860

extension of Paris. Entries located outside the Fermiers

généraux wall in the 1845 directory are therefore mostly

geolocated with the 1888 Municipal atlas. However, the urban fabric of Parisian

edges between the pre- and post-1860 underwent dramatic changes, and the

geocoding is less accurate here than in the city center.

A meticulous manual study of the addresses geolocated in these areas in 1845

reveals various problems in the outcome of the SoDUCo automated pipeline chain

(Figure 12 and 13).

Leaving aside complete failures of the geocoding processing caused here by a

myriad of peculiar forms in the addresses extracted from the directories, three

typical borderline cases can be identified and summarized:

-

Erroneous NER. Bad geolocations are linked to poor or

imperfect recognition of entities by the NER. This is easily identifiable

when the address text is made up of weird character strings or irrelevant

words. But it can be more difficult to detect when the false-address is

plausible enough to be associated with an address in the gazetteer. The

geocoder provides a procedure for excluding some identifiable cases (custom_catchall_alwaysvalid in Figure 12), but

incorrect parsing raises the question of how to handle complex address

descriptions, which can sometimes be fragmented into several directory

addresses.

-

Incorrect street name in the directory. In few cases,

the directory itself provides incorrect information, which has an impact on

the geocoding processing (mainly spelling mistakes and typos).

-

Street absent in the gazetteer. Sometimes the gazetteer

is incomplete or inaccurate. Some streets, attested by their frequency of

appearance in a directory, are not present in the gazetteer (e.g. Napoléon

quay). In other cases, streets are present but without numbers. In this

case, the geocoding process may favor another gazetteer offering addresses,

even if the temporal consistency loses quality.

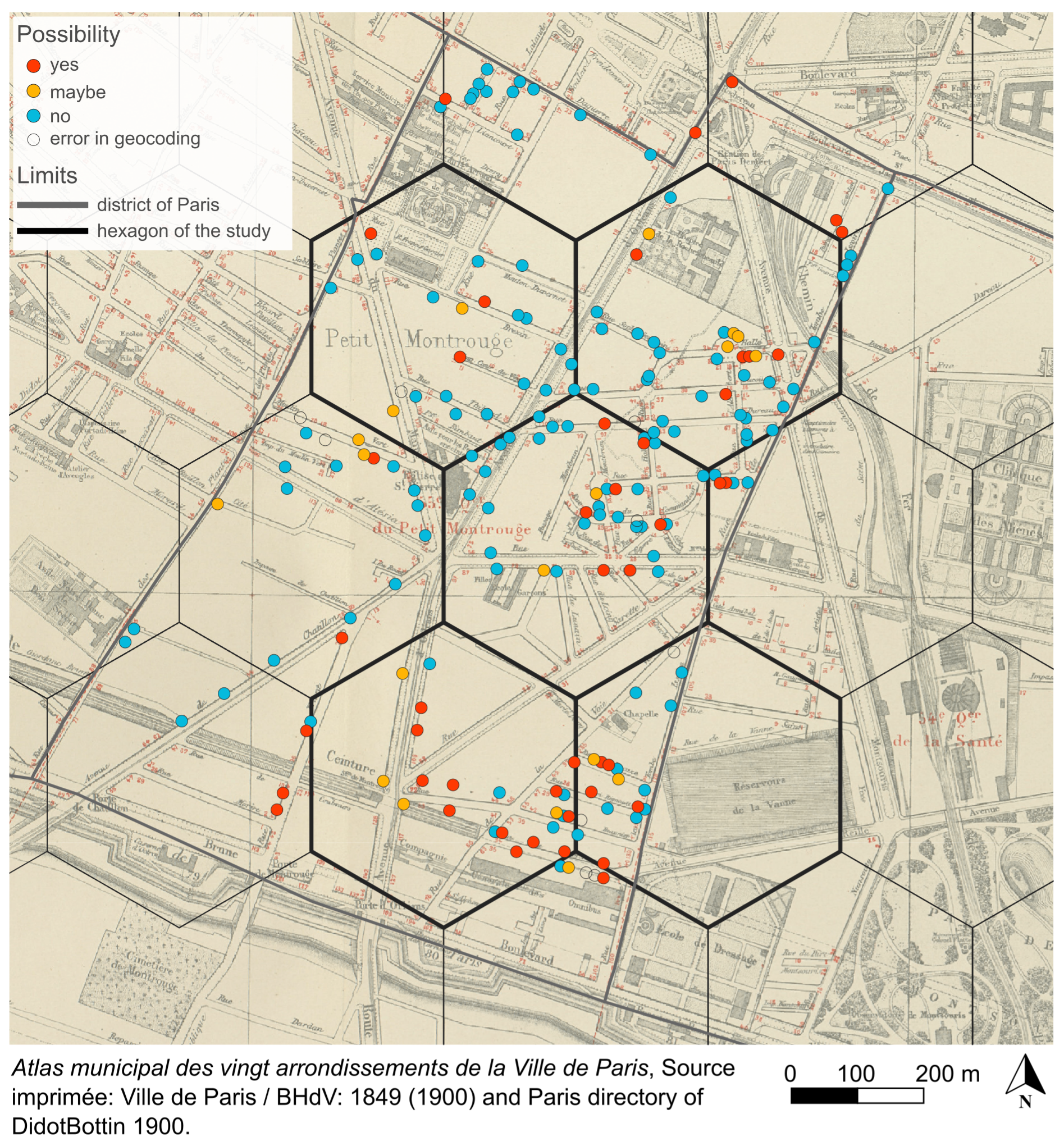

8.4. The dynamics of commercial and wealthy areas of the Petit Montrouge

district in 1900-1904 (14th arrondissement)

Figure 8 shows that the density of geolocated addresses on five hexagons located

in the Petit Montrouge district, south of Paris in the 14th arrondissement, fell

sharply between 1900 and 1904 compared to the whole Paris area (green hexagons in

Figure 8). In order to better understand these spatial dynamics, we examine each

entry from the 1900 Didot-Bottin directory list in this district that is missing

from the 1904 list.

There are 222 directory entries corresponding to the 193 different geolocated

addresses in the study area (Figure 14). We analyze each entry to determine

whether or not it is possible that the disappearance of geolocated addresses

between 1900 and 1904 may be the result of the publication of the Bottin mondain, i.e. an individual no longer appears in the

general list because he or she has been included only in the Bottin mondain by the editors.

A previous study of the Didot-Bottin directories shows that the entries which

disappear from the general lists after 1903 are mainly those of individuals

designated as owners and annuitants, and to a lesser extent, those affiliated with

public administration, e.g. deputies, directors of an institution, etc. [

Gravier and Barthelemy 2024]. We therefore hypothesize that the 1900 entries

referring to owners, annuitants or churchmen are most likely included in the

Bottin mondain in 1904 (N=45

geolocated addresses, in red in Figure 14). However, this is impossible if they

refer to small merchants or craftsmen (N=120, in blue in Figure 14). For other

professions, such as intellectuals (N=19, in orange), this possibility remains

open.

The cartographic result of this systematic qualitative study, presented in Figure

14, shows a significant north/south differentiation between the five hexagons in

sharp decline initially identified in Figure 8. Indeed, geolocated addresses

present in the 1900 directory and no longer present in 1904 mainly refer to small

craftsmen and merchants in the three northern hexagons (see blue dots in Figure

14), while they tend to be owners in the two southern hexagons (see red dots). The

decrease in the density of geolocated addresses in this district is probably due

to an important reorganization of the economic fabric in the north, combine with

the source effect of the publication of the Bottin mondain in the south.

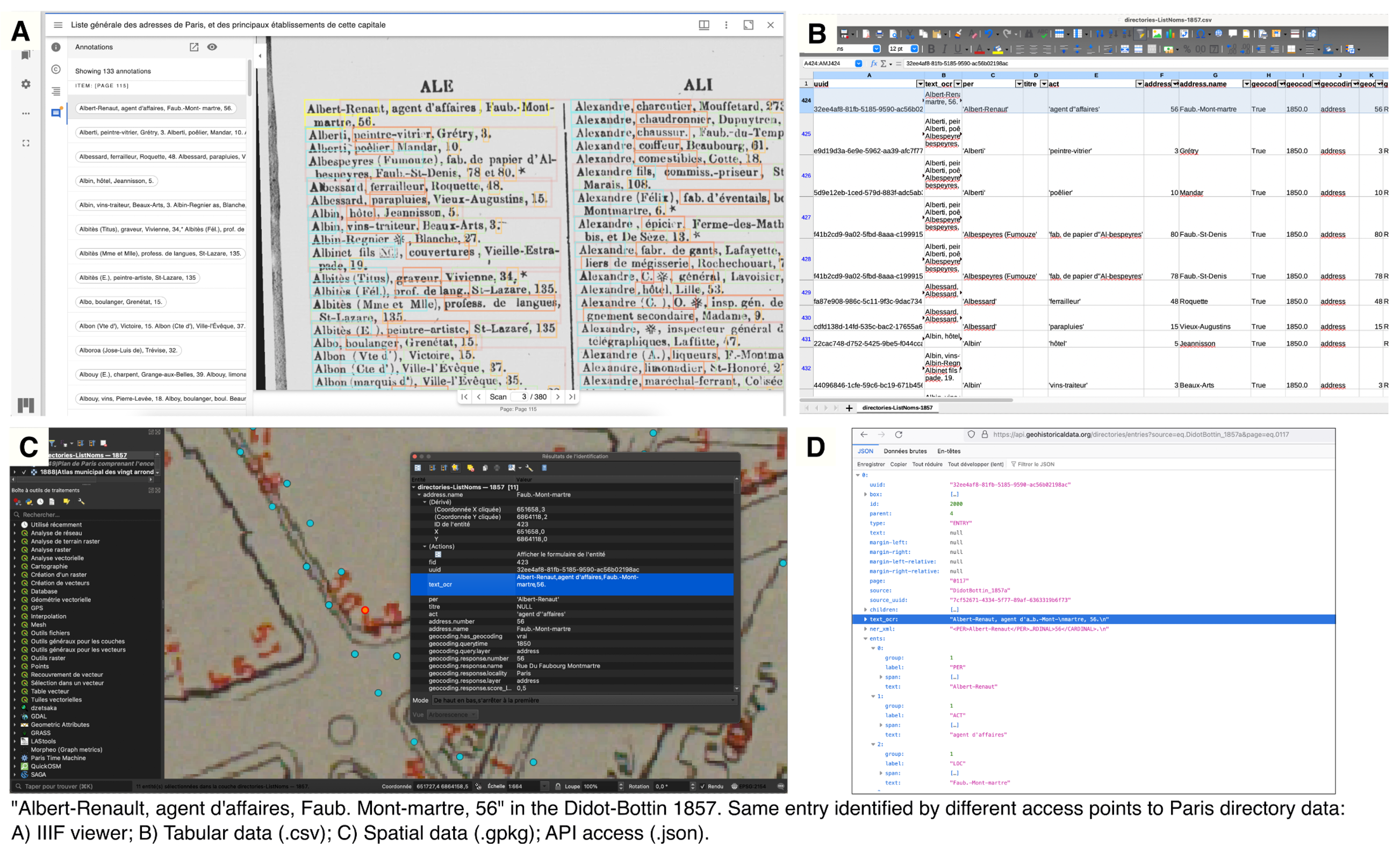

8.5. Parisian directories data access points

Four ways of accessing Paris directories data have been developed, as shown in

Figure 15. Open tabular and spatial datasets supported by documentation that can

be downloaded from the Nakala data archive repository, developed by Huma-Num

infrastructure of the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) [

GeoHistoricalData 2023]; a IIIF viewer

[16] for displaying one or more directory lists with the results of OCR and

NER, and allowing page-by-page downloading of the data displayed; an API REST for

direct querying the PostgreSQL database

[17]. All these services are hosted by the CC-IN2P3 of the CNRS.

Works Cited

Abadie et al. 2022 Abadie, N., et al. (2022)

“A benchmark of named entity recognition approaches in historical

documents application to 19th Century French directories”, in S. Uchida, E.

Barney, and V. Eglin (eds)

Document Analysis Systems.

Cham: Springer International Publishing (Lecture Notes in Computer Science), pp.

445–460. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06555-2_30.

Åhlfeldt, Berman, and Wick 2016 Åhlfeldt, J., Berman, M.L. and Wick, M. (2016) “Historical

Gazetteer System Integration: CHGIS, Regnum francorum Online, and

GeoNames”, in M.L. Berman, R. Mostern, and H. Southall (eds) Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press (The Spatial Humanities), pp. 110–125.

Albers and Kappner 2023 Albers, T.N.H. and Kappner,

K. (2023)

“Perks and pitfalls of city directories as a

micro-geographic data source”,

Explorations in

Economic History, 87, p. 101476. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2022.101476.

Andriveau-Goujon 1868 Andriveau-Goujon, E.

(1868)

“Plan d'ensemble des travaux de Paris à

l’échelle de 0,001 pour 10 mètres (1/10 000) indiquant les voies exécutées et

projetées de 1851 à 1868”. Paris: E. Andriveau-Goujon. Available at:

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530068310(Accessed: 25 February

2024).

Baciocchi and Cristofoli 2022 Baciocchi, S. and

Cristofoli, P. (2022)

“Inventaire des ouvrages

proposant des listes d'adresses parisiennes entre 1780 et 1914”. Available

at:

https://shs.hal.science/halshs-04526443(Accessed: 25 July

2024).

Barthelemy et al. 2013 Barthelemy, M. et al.

(2013)

“Self-organization versus top-down planning in the

evolution of a city”,

Scientific Reports,

3(1), p. 2153. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02153.

Bell et al. 2020 Bell, S. et al. (2020)

“Automated data extraction from historical city directories: The rise

and fall of mid-century gas stations in Providence, RI”,

PLOS ONE, 15(8), p. e0220219. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220219.

Bonvalet and Tugault 1984 Bonvalet, C. and Tugault,

Y. (1984)

“Les racines du dépeuplement de

Paris”,

Population, 39(3), pp. 463–481.

Available at:

https://doi.org/10.2307/1532898.

Bottin 1820 Bottin, S. (1820)

Almanach du commerce de Paris, des départemens de la France et des

principales villes de l’Europe. Paris: bureau de l’Almanach du commerce.

Available at:

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1245624.

Brée 2020 Brée, S. (2020)

La population de la région parisienne au XIXe

siècle, in

Paris, l’inféconde : La

limitation des naissances en région parisienne au XIXe siècle. Paris: Ined

Éditions (Études et enquêtes historiques). Available at:

http://books.openedition.org/ined/1496(Accessed: 16 February

2023).

Carr, Olsen, and White 1992 Carr, D.B., Olsen, A.R. and

White, D. (1992)

“Hexagon Mosaic Maps for Display of Univariate

and Bivariate Geographical Data”,

Cartography and

Geographic Information Systems, 19(4), pp. 228–236. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1559/152304092783721231.

Cottereau 1997 Cottereau, A. (1997)

“The fate of collective manufactures in the industrial world: the

silk industries of Lyons and London, 1800–1850”, in C.F. Sabel and J.

Zeitlin (eds)

World of Possibilities: Flexibility and Mass

Production in Western Industrialization. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press (Studies in Modern Capitalism), pp. 75–152. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511563652.003.

Cristofoli and Baciocci 2024 Cristofoli, P. and

Baciocchi, S. (2024)

“Distribution annuelle des

principales collections et séries d'ouvrages proposant des listes d’adresses

parisiennes (1780-1914) avec mention de la disponibilité d’une version numérique

librement accessible de chaque ouvrage et des sources cartographiques et types de

numérotation associées à la période”. Available at:

https://shs.hal.science/halshs-04526423

Cura et al. 2018 Cura, R. et al. (2018)

“Historical collaborative geocoding”,

ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 7(7), pp. 1–29. Available

at:

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi7070262.

Daras, Feng, and Dibben 2015 Daras, K., Feng, Z. and

Dibben, C. (2015) “HAG-GIS: A spatial framework for geocoding

historical addresses”, in. GIS RESEARCH UK 2015:

Annual Conference University of Leeds, Leeds.

de Maupeou and Saint-Raymond 2013 de Maupeou, F. and Saint-Raymond, L. (2013) “Les “marchands de tableaux” dans le Bottin du commerce: une approche

globale du marché de l’art à Paris entre 1815 et 1955”, Artl@s Bulletin, 2(2), p. Article 7.

Denis 2015 Denis, V. (2015)

“The

Parisians, the police and the house numbering, from the 18th century to the

Empire”,

French Historical Studies, 38(1), pp.

83–103. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1215/00161071-2822709.

di Leonardo et al. 2019 di

Leonardo, I. et al. (2019)

“Repopulating Paris: Massive

extraction of 4 Million addresses from city directories between 1839 and

1922”, in

Digital Humanities conference

DH2019. Utrech: Utrech University. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.34894/MNF5VQ.

Evangelista and Beskow 2018 Evangelista, P.F.

and Beskow, D. (2018) “Geospatial point density”, The R Journal, 10(2), pp. 347–356.

Faure 2004 Faure, A. (2004)

“Spéculation et société: les grands travaux à Paris au XIXe

siècle”,

Histoire, économie &

société, 23e année(3), pp. 433–448. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.3917/hes.043.0433.

Firmin-Didot and Firmin-Didot 1845 Firmin-Didot, A. and Firmin-Didot, H. (1845)

Annuaire général du commerce, de l’industrie, de la magistrature et de

l’administration. Paris: Firmin-Didot frères. Available at:

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6292987t.

Firmin-Didot and Firmin-Didot 1857 Firmin-Didot, A. and Firmin-Didot, H. (1857)

Annuaire-almanach du commerce, de l’industrie, de la magistrature et de

l’administration: ou almanach des 500.000 adresses de Paris, des départements et

des pays étrangers: Firmin Didot et Bottin réunis. Paris: Firmin-Didot

frères. Available at:

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6305463c/.

Firmin-Didot and Firmin-Didot 1903 Firmin-Didot, A. and Firmin-Didot, H. (1903)

Annuaire-almanach du commerce, de l’industrie, de la magistrature et de

l’administration : ou almanach des 500.000 adresses de Paris, des départements et

des pays étrangers : Firmin Didot et Bottin réunis. Paris: Firmin-Didot

frères. Available at:

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k3208950j.

Frondizi 2018 Frondizi, A. (2018) Paris au-delà de Paris : urbanisation et révolution

dans l’outre-octroi populaire, 1789-1860. PhD Thesis. Paris: Institut d’études

politiques de Paris - Sciences Po.

GeoHistoricalData 2023 GeoHistoricalData

(2023)

“Annuaires historiques parisiens, 1798-1914.

Extraction structurée et géolocalisée à l'adresse des listes nominatives par ordre

alphabétique et par activité dans les volumes numérisés”. NAKALA. Available

at:

https://doi.org/10.34847/nkl.98eem49t.

Grange 1996 Grange, C. (1996) Les gens du Bottin mondain: y être, c'est en être. Paris,

France: Fayard.

Gravier and Barthelemy 2024 Gravier, J. and

Barthelemy, M. (2024)

“A typology of activities over a century of

urban growth”,

Nature Cities, 1(9), pp.

567–575. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-024-00108-7.

Gribaudi 2009 Gribaudi, M. (2009)

“Ruptures et continuités dans l'évolution de l’espace

parisien. L’îlot de la Trinité entre les xviiie et xixe siècles”,

Histoire & mesure, XXIV(2), pp. 181–220.

Available at:

https://doi.org/10.4000/histoiremesure.3959.

Gribaudi 2014 Gribaudi, M. (2014) Paris ville ouvrière: une histoire occultée,

1789-1848. Paris, France: La Découverte.

Gribaudi and Blum 1990 Gribaudi, M. and Blum, A.

(1990)

“Des catégories aux liens individuels :

l'analyse statistique de l’espace social”,

Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations, 45(6), pp.

1365–1402. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.3406/ahess.1990.278914.

Gribaudi and Blum 1993 Gribaudi, M. and Blum, A.

(1993)

“Les déclarations professionnelles.

Pratiques, inscriptions, sources”,

Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations, 48(4), pp. 987–995.

Available at:

https://doi.org/10.3406/ahess.1993.279186.

Grossner and Mostern 2021 Grossner, K. and Mostern,

R. (2021)

“Linked Places in World Historical Gazetteer”,

in

Proceedings of the 5th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop

on Geospatial Humanities. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing

Machinery (GeoHumanities ’21), pp. 40–43. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1145/3486187.3490203.

Hedefalk et al. 2018 Hedefalk, F. et al. (2018)

“Importance of the geocoding level for historical demographic

analyses: A Case Study of rural parishes in Sweden, 1850–1914”,

Spatial Demography, 6(1), pp. 35–69. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40980-017-0039-7.

Hersent et al. 2023 Hersent, M. et al. (2023)