DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly

Editorial

Image Reuse in Eighteenth-Century Book History: Large-Scale Data-Driven Study of Headpiece Ornament Variants

Abstract

This study uses large-scale computational analysis to trace the reuse of decorative headpieces in eighteenth-century books. The results highlight how image variants reveal complex networks of printers and publishers beyond simple one-to-one ownership.

Introduction

In the handpress era of book production (c. 1450–1800), many works contained ornamental

or illustrative elements, alongside the printed text. These graphical elements ranged

from large, detailed engravings and woodcuts to small pieces of decorative type, known

as fleurons. The study of these elements is integral to the understanding of the history

of the book, for instance, charting graphical innovation in the eighteenth-century

novel [Barchas 2003]. Graphical elements have been particularly useful to bibliographic studies. The

study of the printers’ devices, for example, can be used — in some cases — to identify

the bibliographic details around which a particular book was published [Wilkinson, Briggs, and Gorissen 2021]. Computational analysis allows us to scale up this research. The main advantage

of modern computational techniques is that we approach the material in a data-driven

fashion, without any assumptions on image use in the collection. On the contrary:

in this paper we demonstrate how data-driven grouping of visual devices reveals hidden

patterns and unknown regularities of ornament circulation.

One main focus in this paper is headpiece —a large decorative illustration placed

usually at the top of a page. These headpieces, as with other ornaments, were impressed

onto the page with ink, with a reusable carved or engraved template. The images which

form the objects of study here are therefore most of the time repeated copies of a

certain woodcut [Mosley 2009]. Although we are broadly interested in all these different types of images, our

goal here is to examine how headpieces, and especially their variants and close copies,

relate to the book trade and its various actors. This approach allows us to go beyond

simply creating a finding aid or presenting a one-off case study and instead investigate

the deeper significance of the varied nature of the headpieces within eighteenth-century

publishing.

The discipline of book history has a tradition of scholarship with the goal of identifying

a specific printer’s ornament stock. This approach was notably advanced by Keith Maslen’s

(1973) study of the London printer William Bowyer (1699–1777). Bowyer is a particularly

valuable subject for this kind of study because his printing ledgers have survived,

meaning the books he printed can be definitively verified. Maslen examined all the

books recorded in Bowyer’s ledgers, extracted the ornaments from those books, and

argued that these ornaments were Bowyer’s, based on the assumption that Bowyer owned

the woodblocks that created these images. Maslem’s focus was on one-to-one matching

between an ornament and Bowyer. Subsequent major studies on printer's ornaments, focusing

on Richardson [Maslen 2001] and Woodfall [Goulden 1988], assert ambitions akin to Maslen's original study. As we demonstrate in this article,

variants of ornaments were widespread, and are, we believe, an underutilised source

of evidence for printing and publishing practices in the eighteenth century. Understanding

the use of these variants, in combination with the idea that, for example, Bowyer

owned certain woodblocks, offers an interesting perspective.

This practice of matching headpieces to a single printer works fine if we are only

interested in these individuals. A broader perspective emerges when we track ornaments

and their variants at scale. In this pilot study, we combine a large, representative

sample with computational methods to reveal that the printer–publisher landscape in

the eighteenth century was far more complex than a simple one-to-one link between

an ornament and a single printer. In particular, major publishing houses like Tonsons

— employing multiple printers — may have actively shaped the distribution and consistent

use of certain designs, potentially extending their “house style”, even to Irish editions.

While we do not claim conclusive proof of this in our proof-of-concept study, we highlight

new avenues of exploration — such as the role of publishers in orchestrating ornament

use — supported by corroborative examples.

Our hypothesis is that printers were not the only ones to own woodblocks: publishers

either owned them too or had preferences towards particular styles or blocks and allocated

them to printers for specific projects. The border between publishers and printers

was not strict in the handpress era and, for example, many book trade actors who started

out as printers ended up as publishers. When operations grew, publishers engaged different

print shops for a single publication, provided the paper (e.g. [Bidwell 2010, 215–216]) and orchestrated the production while printers of different capacity executed

the tasks (about complexities of copyright ownership of books beyond legal disputes,

cf. [Belanger 1975]; [Treadwell 1982]). It is therefore unlikely that publishers did not have a hand in selecting and

coordinating the use of certain ornaments. Moreover, publishers, such as the most

famous eighteenth-century publisher, Jacob Tonson and his successors, within their

“publishing house” (a term which we refer to their full operation of producing their

products) worked closely, but not exclusively, with certain printers. This scenario

underscores the complexity and still evolving nature of the print industry, suggesting

that the distribution of different woodblocks likely involved a more complex story

and a larger network than previously understood (about different techniques to produce

duplicate images, see [Mosley 2009, 184–185]).

Our argument is that complex dynamics were at play in the production and dissemination

of printed materials, challenging simplistic narratives about ornament ownership and

usage in the eighteenth-century publishing landscape. Additionally, these dynamics

were influenced by the various places of publication. In our use case, we examine

the cross-border relations between London and Dublin, revealing patterns in the use

of near variants of particular ornaments. These patterns suggest use that goes beyond

the notion of a single printer owning a specific set of woodblocks for creating ornaments.

To grasp this complexity, we employ computational methods..

This article explores the extent to which a computational analysis of headpiece ornaments

can illuminate the printing practices of the eighteenth century. The article serves

as a proof of concept, demonstrating that:

a) Machine learning can be employed to cluster hundreds of thousands of headpiece

ornaments from the Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO) database, providing meaningful insights into book history, by identifying

patterns in the use of these ornaments.

b) By integrating bibliographic metadata with the results of image classification,

this can reveal the networks of publishers and printers associated with ornaments

and their variants, highlighting intentionality in ornament reuse.

State of the art

Previous studies have worked on the assumption that ornaments generally belonged to

the stock of a particular printer and used that as the basis for analysis ([Maslen 1973]; [Maslen 2001]; [Goulden 1988]) see also [Ross 1990]. As mentioned, the approach here differs in that a) it does not focus on specific

printers and b) we also track close copies of individual ornaments. We adopt an agnostic

and large-scale perspective on headpieces, organising them based on the comprehensive

data available in ECCO, a source of approximately 200,000 digitised books (33M pages),

mostly printed in Britain, Ireland, and North America, digitised by the software company

Gale (on the ECCO as data, see [Tolonen, Mäkelä, and Lahti 2022]).

[1]

This allows us to examine headpieces and their variants, in all their complexity and

through the changing of hands, within the broader context of eighteenth-century printing

practices.

Detecting and classifying visual elements in digitized historical texts is useful

for a variety of downstream tasks, for example identifying the printers of books where

such information was previously unknown ([Wilkinson 2013]), or establishing the order in which different editions of a work were printed [Bergel, Howe, and Windram 2014]. More recent and ambitious work has approached the printing process as a whole,

in order to reveal the circulation of images, printers’ practices, and iconographic

traditions [Dondi et. al 2020]. In order to do this, large-scale processing of a book collection is necessary,

which is increasingly feasible by the means of modern machine learning techniques,

which are able to recognize and group images at scale.

For the ECCO collection, such analysis has been previously done within the Compositor

project [Wilkinson, Briggs, and Gorissen 2021]. The Compositor database was created on top of ECCO books by computationally extracting

all printer ornaments found within the digitised pages of the collection. Additionally,

a ‘visual search engine’ was created which enables the discovery of similar images.

There are some limitations, for instance there is no functionality to classify extracted

images into more specific categories such as headpiece or decorative initial. Other

projects specifically focused on the detection of decorative initials ([Uttama 2006]; [Nguyen, Coustaty, and Ogier 2020]), extracted decorative initials and clustered the results to aid the discovery of

document provenance ([Hu et al. 2015]), and made illustrations available for visual analysis [Dutta, Bergel, and Zisserman 2021].

It has been suggested that scanned pages within ECCO are not suitable for distinguishing

the smallest details and deciding whether two images are made from the same woodblock

[Wilkinson 2013]. We agree that the quality of ECCO images introduces complexities to the process,

but we aim to show in this paper that the ECCO data can still be used to address a

wide variety of questions related to the circulation of images. However, this requires

a shift of perspective from a single image or a specific work to broad sets of similar

images that consists of both exactly matching images and semantically clustered versions

[Chung et. al 2015].

Methodology

In practical terms, the article refers to a very large number of images and image

sets. These have been automatically extracted, classified and grouped together, and

then re-grouped and checked with extensive manual annotation. As the article refers

to so many image sets, they have been given unique codes which are used throughout

the text and refer to images found in the appendix. The code consists of two parts:

first, an alpha-numerical code (e.g. C123_04), and second, a code consisting of a

number of more humanly-readable keywords. The alphanumeric codes follow pattern CXXX_XX,

where the first three numbers are main class code and the last two are subclass code.

Additionally, we used a large language model to generate descriptive titles from each

image’s key features (e.g., botanical details), limiting output to under 12 lowercase

words without frequently occurring words (like ornamental), which allows enhancing

the overall consistency of our nomenclature. For example, the top image in Figure

1 has the identifier C002_01 and titled “mercury_head_with_crossed_trumpets_floral_borders_0”.

Henceforth in this paper we refer to image classes and subclasses using codes and

titles from the Appendix.

We refer to the broad phenomena we are studying in this paper as image reuse, which includes a range of practices from reproduction, woodblock lending, intentional

production of several copies, to simply using the same generic motif. The procedure

we propose is data-driven: it allows us first to detect the general fact of image

reuse and then go deeper into distinguishing the specific cases.

To that end, we extracted all headpieces from ECCO and grouped them according to their visual similarity, without

any assumptions on what can and cannot be grouped. We then distinguished between close similarity and remote similarity of the images. We organized all extracted images on two levels: groups

of closely similar headpieces were combined into bigger classes of remotely similar

headpieces, due to deliberate copying, reproduction, or simply a similar or generic

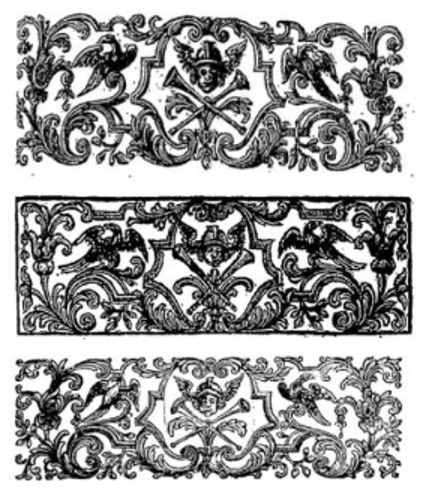

motif. For example, in Figure 1 we show three headpieces that belong to three different

subclasses inside the same class.

Figure 1.

Example of a similar image (C002_01; C002_02; C002_03) Three headpieces that look

very similar but bear subtle differences (e.g. different flora at the corners) and

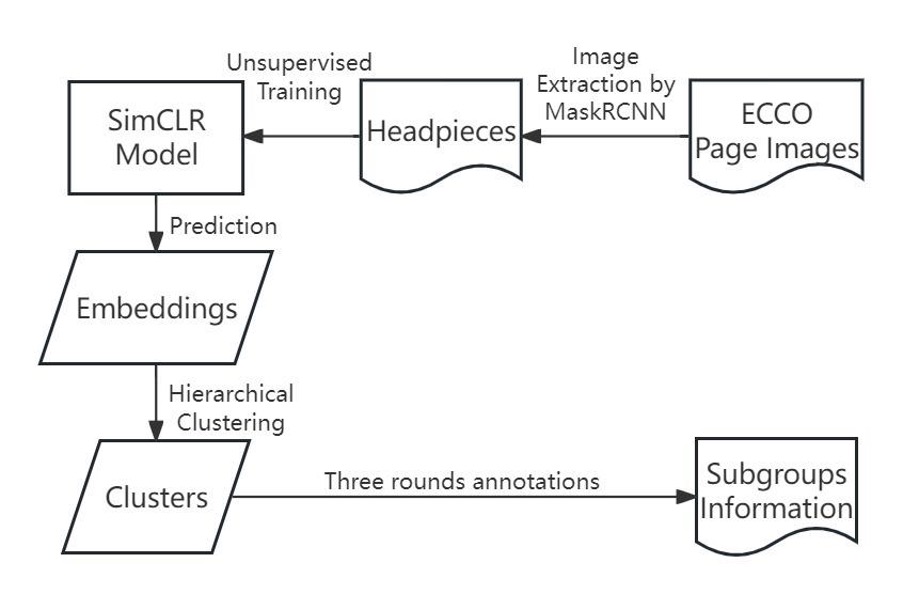

thus belonging to the same superclass but to different subclasses.In Figure 2 we show a workflow diagram of our processing pipeline. The first step

is printmark detection using a neural object detection model. The method is described in (Wang, 2023); the

headpiece extraction works with 94% accuracy, which means that our dataset contains

almost all headpieces in ECCO, and, according to manual inspection, the vast majority

of images in the dataset are indeed headpieces. However, in some cases they are used

for different roles, e.g. situated in the middle of a page rather than on top. Images

are extracted automatically, and we do not impose additional limitations on how they

are positioned.

The next step is image representation learning, i.e. training a model that assigns to each image an embedding, i.e. vector representation, in such a way that similar images have similar representations.

We used the SimCLR model ([Chen et. al 2020]), which can be trained without using manually annotated examples. To that end, we

automatically produce two slightly different versions of each image, e.g. by applying

random cropping, rotating and blurring. Images are then run through a neural network

that outputs image embeddings. We use a standard convolutional ResNet network with

50 layers for that purpose [He et al. 2016]. Then the model is optimized in such a way that it produces similar outputs for

two versions of the same image and dissimilar for other image pairs.

Image processing workflow

Since this work is the first that applies this approach to book ornaments, we evaluated

the model using manual annotation. First, we randomly chose 2000 pairs of headpieces

in such a way that this test set consisted of pairs with diverse, both high and low,

similarity scores. Then we manually annotated these pairs: the task for the annotators

was to judge whether two given visual elements are matched. Comparing these annotations

with our best representation model, we found that representation works with 95% precision.

However, high-quality pairwise similarity by itself does not imply meaningful image

grouping due to peculiarities in clustering algorithms. Thus, we conducted a separate

evaluation of image clusters, using additional 1500 headpieces which we manually grouped.

We clustered the whole dataset and then evaluated clustering performance for those

headpieces. We experimented with several clustering methods and found that Hierarchical

Clustering is the best performing for our data, resulting in 60% performance.

We examined a few instances where the output of the best model differs from manual

annotation. It seems that in many cases false positive pairs are very similar, as

in Figure 3 which suits our broad definition of image reuse and can serve as an initial

step in a more complex analysis.

Figure 3.

Headpieces with similar patterns C011_02 and C011_01. Two very similar headpieces

where a central character is looking in opposite directions.We then conducted image extraction across the entire ECCO dataset and trained a bigger

SimCLR model using 709,299 headpieces. Training with the full ECCO image set allowed

the model to capture more complex and subtle differences across the visual elements.

In the next step, we applied hierarchical clustering to the representations obtained

from this SimCLR model. To reduce computational costs of the clustering we focused

only on broad headpieces, with the smallest width to height ratio. Such headpieces

contain more detailed images, were used in more expensive books and most relevant

for our use case analysis. Although very narrow ornaments may have been reused more

often, for example as dividing rules, their lack of detail make them computationally

more difficult to distinguish, particularly when taking into account the focus here

on variations. Very narrow headpieces are often very common or generic ornaments;

an extreme case is that the image with a ratio more than 10 is close to a simple ornamental

line and hence is not representative in finding potential printer information. We

also noticed during manual annotation that these headpieces are more often incorrectly

grouped together since they do not bear enough information for the model (or a manual

annotator for that matter) to discriminate — this decision was also taken, therefore,

for pragmatic technical reasons.

In this pilot case, we want to focus on the large clusters that cover as many printers

and publishers as possible. As our evaluation showed, the model can capture pairs

of similar images, but complete clustering of the whole dataset is more problematic.

Since very accurate results were needed for useful historical evidence, we conducted

manual post-correction.

To do this, we checked the clusters manually predicted by the model and first examined

the large clusters with more than 20 images in each cluster. We randomly sampled 5

images from each large cluster to quickly estimate its quality. If at least 4 images

looked similar we chose the cluster for further manual annotation. Next, manual annotation

was performed in two stages: in the first stage we tried to obtain as large parent

classes as possible. In the second stage, we divided them into fine-grained child

classes.

The final result was 172 main classes and 496 subclasses, composed of 15,249 images.

We present all classes in the Appendix, where for each subclass we show an example

image, a year range when it was in use, a count of hits (separate usages) and the

number of books in which it was found. In addition, each class has a title that was

given to it for visual clues for annotation purposes.

Case Study

Comparing previous work on ornament stocks with our data

After completing the classification, we manually compared our subclasses with the

bibliographies which give instances of the headpieces used by three different printers:

Samuel Richardson ([Maslen 2001]), Richard Bowyer ([Maslen 1973]) and Woodfall ([Goulden 1988]). In essence, we looked through these works and matched the images to our own clusters.

We could then compare the results, for instance by comparing the date range for which

a headpiece was known to have been used to the results in the clusters. For Richardson,

270 ornaments were cross-checked, for Woodfall 214, and for Bowyer 112. As a result

of this check, 49 of our classes matched with Richardson, 37 with Woodfall, and 24

with Bowyer. The reason why we do not get matches with all of their ornaments is that

we have taken a random, representative sample of more often used headpieces at this

stage to use as a proof-of-concept to evaluate the earlier results and printing practices,

rather than categorising every single headpiece.

| The average class size for manual analysis data | The average class size for our matched data | The average lifespan for manual analysis data (years) | The average lifespan for our matched data (years) | |

| Bowyer | 28,87 | 44,5 | 29,45 | 34,12 |

| Richardson | 23,77 | 32,97 | 21,63 | 24,16 |

| Woodfall | 9,37 | 34,29 | 8,78 | 23,67 |

| All our headpiece data | 23,39 |

Table 1.

Average usage interval for the ornaments.Table 1 compares the average lifespan for headpieces in previous studies to that detected

by the computational methods used here. In our analysis, lifespan is calculated for

all usages of the image, regardless of who used them.

This suggests that computational methods are useful to find more comprehensive sets

of related images than by a manual approach alone. To take an example, Goulden’s work

on Woodfall’s ornament stock found considerably fewer examples in comparison to those

found in our data. Additionally, the date range (or lifespan) of the images is notably

shorter: Goulden found evidence of the survival of ornaments over an average range

of about 8 years, whereas the equivalent clusters in our data have an average lifespan

of just over 23 years. While some of this disparity may be attributed to methodological

differences, it also makes clear that leveraging computational approaches, which enable

the search and analysis of images over a much wider time range and larger set of data,

can improve our knowledge and understanding of the subject.

Comparing previous work on ornament stocks with our data

An often overlooked aspect of eighteenth-century publishing is the dynamic between

London and other centres of English-language publication [Ryan and Tolonen 2024]. English books were often reprinted in Ireland, a practice which was known for its

lower production costs and quality, potentially resulting in higher profits for all

parties involved. Therefore, London publishers formed alliances with Irish printers

to produce economical Dublin editions of their titles. By investigating the variations

of headpieces across different editions of the same work, as well as across distinct

works, we can unveil such practices and gain an understanding of the reuse of images.

Recent scholarship has moved beyond the outdated view of all Irish eighteenth-century

printing as piratical, instead highlighting potential collaborative ventures (cf.

[Rumbold 2020, 174–176]; [Benson 2010, 170–172], see also [Feather 1987] and [Harris 1996]). While the use of ornaments does not alone indicate such relationships, we aim

to show that their systematic analysis reveals distinct patterns of usage, thereby

shedding light on certain facets of the publishing trade. In this section we offer

few straightforward examples that showcase how the examination of headpieces can be

used to shed new light on certain aspects of the printing connections between Dublin

and London.

Our analysis of headpieces suggests particular collaborations between London and Dublin,

aligning with the well-established relationship between Bowyer and the prominent Irish

printer George Faulkner. This confirms that our system effectively captures historical

connections identified through traditional scholarship, allowing us to build on these

findings and uncover further patterns of collaboration. Both [Rumbold 2020, 174] and [Pollard 2000, 198] note that Faulkner’s eclectic use of ornaments suggests he borrowed from various

printers' stocks. By examining comprehensive sequences of ornament usage, rather than

focusing on the inventory of a single printer, we have identified instances of ornaments

exchanging hands. For example, Bowyer and Faulkner used three unique, identical-looking

ornaments, indicating these were likely transferred from Bowyer to Faulkner, who had

been working for Bowyer until 1729. While earlier scholarship has established that

Faulkner sourced some ornaments from Bowyer, what remains unexplored are the variations

within the Bowyer-Faulkner connection and the broader use of Bowyer-associated ornaments

in Ireland. The fact that we can now identify these patterns computationally — without

relying on archival records — demonstrates the effectiveness of our method and provides

a foundation for further analysis.

One of our objectives with the images extracted and classified by the computational

means has been to identify close copies. Excessively long runs of the same image in

different places of publication may suggest that they are copies rather than the same

image. As an example, the ornament in Figure 4 can be found in books almost 75 years

apart. To both the clustering algorithm, and in this case, to the naked eye, these

images seem to be from an identical block, but we can speculate that in fact there

existed several copies of the image. With the right data, it may be possible to identify

such cases.

Figure 4.

Headpiece centered_shell_in_leafy_ring_flanked_by_pots_and_snails_0 (C127_01) the

first recorded use in 1710 on the left and the last recorded use in 1786 on the right.

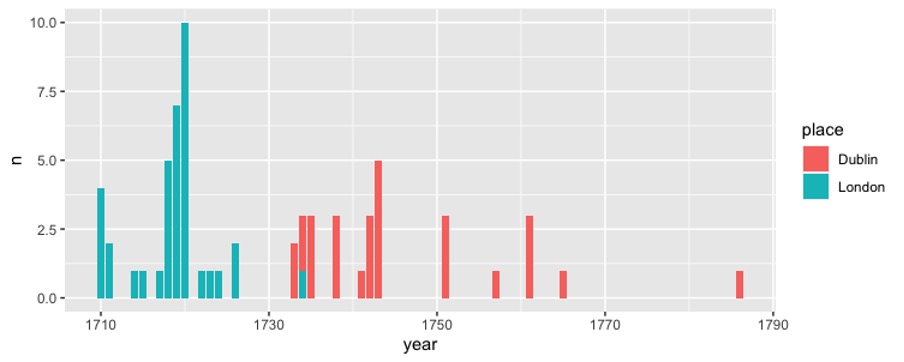

Two practically identical headpieces found in the data 75 years apart.The timeline of this headpiece in Figure 5 illustrates its extensive use in Dublin,

despite being initially linked only to Bowyer. While Bowyer's use is documented in

22 volumes, we have recorded a total of 50 instances, highlighting a notable temporal

shift: Bowyer used it until the early 1720s, and Faulkner's use begins after 1733.

This pattern is also observed with other headpieces.

Figure 5.

Use of the above centered_shell_in_leafy_ring_flanked_by_pots_and_snails_0 (C127_01)

by place. A histogram showing that until 1730s all instances of the headpiece were

found in London publications, while after that date most instances with very few exceptions

are found in Dublin publications.Furthermore, the employment of Bowyer's ornaments and their close variants in Dublin

extends beyond Faulkner’s use, with the publishing house of Powells also utilizing

the same designs that originated with Bowyer. Despite some exceptions, these ornaments

are unmistakably linked, highlighting the shared use and possible exchange of ornaments

between these printers across geographical boundaries. This complex scenario cannot

be explained by simple lending practices alone. To understand what is happening, we

need comprehensive evidence, and we must interpret individual cases within the broader

context of the totality of ornament data which we intend to do in subsequent research.

Further complexities in ornament reuse

The connection between Faulkner's use of identical headpieces and his link to Bowyer

illustrates the interaction between Dublin and London printing — given that a single

woodblock can only be in one place at any given time. However, the situation becomes

significantly more complex when considering the reuse of variants of a specific headpiece.

In Dublin's printing scene, there were undoubtedly instances of copying and perhaps

even pirating the appearance of London publications. Yet, it is also a plausible scenario

that London publishers occasionally supplied Irish printers with woodblocks, enabling

them to produce works that shared a stylistic resemblance with their London counterparts.

This potential exchange introduces a layer of complexity in understanding the relationships

and practices within the broader publishing landscape.

An interesting possibility involves publishers commissioning woodblocks that represent

variations of the same image, then deploying these in a consistent pattern. Of particular

interest here is what we refer to as the Tonson-Watts enterprise. Rather than treating

Tonson Sr. and Jr. as separate publishers, we aim to study them as one publishing

house, to which we also connect John Watts for practical reasons (following [Foxon 1991]). Within the context of Tonson-Watts publishing, we observe ornaments in Dublin

publications that bear a striking resemblance to those consistently utilised by the

Tonson-Watts enterprise. For the Tonsons, we proceed with the premise that ornaments

frequently featured in their publications might indicate a connection to these works.

If this is the case, the large-scale, computational identification of variants of

woodblocks can help us to understand more about publisher affiliations.

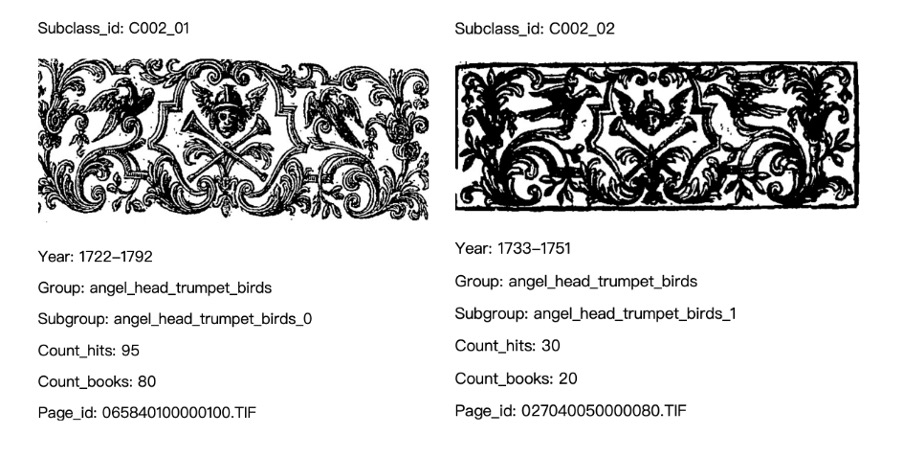

[2]

Figure 6.

Two subclasses of mercury_head_with_crossed_trumpets_floral_borders (C002). Two headpieces

with angel head in the middle that share a common structure but obviously printed

from different wood blocks, accompanied with metadata information.In our study of the Tonson-Watts enterprise, we have identified a series of near-identical

variants utilized by both Tonson and Dublin printers, with examples including "eagle_flower_vines_pedestal_vase_cartouche"

(C057); "cupids_playing_near_fountain_one_kneeling_one_holding_bow" (C065); "harbor_scene_with_multiple_ships_and_buildings"

(C080); and "centered_flower_in_oval_border_with_flanking_baskets" (C101). While these

instances might suggest piracy, that topic falls outside the scope of our current

interest. The origins of these nearly identical ornaments — whether due to a craftsman

producing multiple versions for various publishers and printers, deliberate imitation,

or other factors — are difficult for us to determine and are not our primary focus.

Instead, our investigation centres on ornament reuse that extends beyond simple replication,

as we try to understand the significance of the relationship between two variants

of an ornament, and its implication for the connection between the works and producers

of the works from whence they came.

A particularly striking example of ornament reuse is the “mercury_head_with_crossed_trumpets_floral_borders”

(C002) design, frequently employed by Tonsons in London. As discussed earlier, determining

the rationale behind certain variations can be challenging. However, comparing the

Tonson headpiece (C002_01) with its Dublin counterpart (C002_02) (see Figure 6) reveals

two distinct designs: both feature a central head and trumpets, but in C002_01 the

birds face away from the head, while in C002_02 they turn toward it. C002_01 corresponds

to Tonson/Watts prints in London, whereas C002_02 appears in Irish printing. Similar

patterns can be seen with “mermaid_with_torch_surrounded_by_foliage” (C011_01 & C011_02)

and “centered_owl_with_spread_wings_on_book_surrounded_by_foliage” (C171_01 & C171_02).

This prompts the question of whether such differences reflect Tonson’s own connection

to Irish editions for certain titles. We have found over 20 Irish examples and many

Tonson prints spanning more than three decades. The deliberate way these headpieces

differ — and their consistent use, in contrast to the usually sporadic nature of pirated

ornaments — suggests something more than a simple imitation of a publishing style.

Instead, it may indicate a strategic choice behind retaining and reusing these ornaments.

It is important to clarify that our goal in this paper is not to definitively establish

intentional and authorized use of woodblocks. Instead, we propose this as a plausible

scenario to reconsider the dominant printer-focused narrative. This line of inquiry,

especially concerning Tonson, warrants further exploration to elucidate the complexities

of eighteenth-century publishing practices.

Dublin reprints and reused ornaments

The investigation above looks at reuse, copies and variants of ornaments without regard

to the work in which they appeared. A further aspect that we wanted to test was the

question of the reuse of images and Dublin editions, by looking specifically at ornament

reuse or variant reuse in Dublin editions of existing works. One possibility is that

Dublin printers aimed to counterfeit London editions, copying not just the text but

also the appearance of the London books, including the headpieces. The ECCO contains

multiple editions of the same work, which we have grouped together [Ijaz et al. 2019]. We investigated whether variant headpieces were consistently used across different

Dublin editions of London books. Doing this at scale allows us to state that this

was generally not the case. While similar headpiece variants were found in both London

and Dublin, as described above, they typically did not appear in the same works.

We found that in our data only a handful of copies have any similar images as their

London counterpart. The most definitive example of a Dublin edition modelled after

its London original in our study is John Laurence's A New System of Agriculture, published in London in 1726 and in Dublin in 1727. The Dublin edition's frontispiece

copperplate closely corresponds to the London edition's, albeit not as an exact replica.

Moreover, the initial pages of the Dublin edition — including the headpieces — faithfully

mirror those of the London version, though this does not extend throughout the entire

book. Notably, the Dublin edition employs a variant of the London headpiece (seated_figure_with_bordered_frame_and_holding_object_with_cherubs_1

(C108_02) and seated_figure_with_bordered_frame_and_holding_object_with_cherubs_2

(C108_03)), offering subscribers an edition worth their money.

Laurence's A New System of Agriculture thus stands out as a notable exception in our data. Beyond this, there are only a

few instances where Dublin reprints sought to replicate the images from their London

originals. This does not imply that Dublin reprints lacked images altogether, but

rather, aiming faithfully to copy the exact images from the London editions was not

a widespread practice. However, there are exceptions to this observation that Dublin

reprints did not commonly reuse the same images as their London counterparts. For

instance, John Hughes' Siege of Damascus, published by Tonson in London in 1721, saw its London reprint in 1741 and subsequent

reprints in London (1753) and Dublin (1765) utilising variants of the same image ("harbor_scene_with_multiple_ships_and_buildings"

(C080)). Similarly, James Hervey’s Theron and Aspasio, published in London and Dublin in 1755, featured the "centered_flower_in_oval_border_with_flanking_baskets"

(C101) image.[3]

Moreover, the reprinting dynamic was not exclusive to London and other locations.

Samuel Madden’s Themistocles, initially published in Dublin in 1729, was reprinted forty years later in Cork in

1769, including the same headpiece ("baskets_with_curved_foliage_and_decorative_frame_2"

(C067_03)), an image which featured in different publications in six different cities

(Cork, Oxford, London, Glasgow, and Dublin). Beyond this example, we identified five

additional subclasses of the same ornament, illustrating the complex network of variants

which extends beyond the practices of individual printers.

Discussion

Our work has suggested that the study of close variants of ornaments can play a valuable

role in understanding publisher and printer connections, particularly when computational

methods allow us to do this at scale. These computational methods suggest that the

scale of reuse, copies, and variants is extensive, and moved across different centres

of publication. Even if these studies correctly distinguished between the variants

and focused only on those belonging to a particular printer, the existence of similar

variants raises many unanswered questions. Proper documentation of these distinctions

becomes crucial for accurate identification.

Each printer’s stock (if we want to use such an expression in the first place) and

selection of headpieces was thus diverse and dependent on various factors that are

mostly obscure to contemporary historians. Some, most likely, borrowed ornaments from

major printers or publishers, while others had their own headpieces. Therefore, to

understand the usage and circulation network of headpieces in eighteenth-century Britain

and Ireland, we have aimed to focus on general tendencies through a large dataset,

providing individual examples through our data set where relevant. This has supplemented

the conventional approach that prioritises identifying a specific printer before analysing

their use of ornaments. Our data, including that on Bowyer, reveals the extensive

use elsewhere of ornaments previously attributed to his inventory, providing evidence

of systematic use in works not previously documented. We aimed to provide explanations

for these patterns in selected instances, illustrating the need for a revised understanding

of ornament reuse in eighteenth-century printing.

There are potential pitfalls to be avoided when looking at image reuse at scale. Identifying

minute differences between ornaments and establishing whether they are the same or

copies is a difficult task with good-quality images, and made more difficult with

the mixed image quality of ECCO. Scholars should exercise caution regarding the existence

of variants when leveraging ornaments as evidence of a specific printer's work. Some

headpieces, presumed to be borrowed from another printer's stock — particularly in

Dublin — turn out to be variants of the original ornament. The nearly identical nature

of these ornaments can lead to confusion and misinterpretation due to fragmented evidence.

Care must also be taken not to confuse new editions with reissues of unsold sheets

(usually with a new title page), which was a fairly widespread practice in the eighteenth

century and can identify false cases of reuse. In this case study, examples were manually

checked, but it could easily be done at scale computationally and incorporated into

the workflow. Another important point is that of false imprints: particularly where

a title page states one geographic location for a work actually published elsewhere.

While there is no automatic way of detecting these false imprints through images,

the practice was not, (at least between the Dublin and London publishers discussed

here) widespread enough to refute the broader picture presented here [May 2019, 83]. Additionally, the ESTC bibliographic data often flags false imprints where

they are known, allowing us to exclude them from our results.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have outlined a mixed methodology and workflow for the identification

and analysis of images found in digitised books. The images in question need a new

approach because they are atypical in comparison to other types of images found in

historical sources: they are used repeatedly, their primary purpose is often decorative

rather than semantic, and the handmade process by which they were created, coupled

with the uneven nature of the digitised collections in which they are found means

that straightforward techniques of image recognition need some modification. Our work

has shown that a combination of computational methods with manual annotations and

analysis allows us to reveal image reuse on various levels of granularity. Just as

importantly, we demonstrated the ways in which the resulting data can be operationalised

to tackle key questions relating to the discipline of book history and propose a set

of methods by which this can be achieved. In this way, image recognition and grouping

are a starting point for further investigations, investigations which themselves need

a new set of practices and approaches, involving both close and distant ‘reading’

of the ornaments, as well as visualizations and network analysis.

As we and others have shown, the data from ECCO can be used to study ornaments. A

further question is how we can understand who produced books, given that the metadata

(taken from book imprints) is inconsistent or untrustworthy. We argue that one should

follow consistent patterns of both imprint and ornament practices and combine this

work with external evidence. By working with computational history rather than traditional

bibliographic approaches, studying consistent patterns becomes more effective. This

includes following recent advances in computer vision and other fields of AI. With

the rapid development of these fields, it is often possible to improve results obtained

just a few years ago. However, we argue for even deeper collaboration between the

two fields. In this paper we demonstrate how switching from exact image similarity

to continuous image distances results in a broader inventory of historical book analysis

methods.

At the same time, in order to produce worthwhile results, it is of utmost importance

to do the work to clean up the big data available to us: whether that be the metadata

taken from library catalogues providing evidence on the production of books, or the

information on visual images as we have worked with here. This, we argue, still requires,

and is best carried out, with manual intervention.

While we are not the only researchers using ECCO to explore printers' ornaments, we

believe our work makes a valuable contribution in its serious consideration of variants,

alongside integrating publisher and printer metadata. This novel approach has led

us to rethink how ornament data can illuminate eighteenth-century publishing practices,

moving beyond the simplistic debate on ornament ownership by printers — a reality,

albeit not the sole focus. Our analysis aims to shed light on broader publishing networks,

the practice of employing multiple printers, and the circulation of ornaments through

sales, inheritance, and other means. Furthermore, we suggest that publishers may have

played a more involved role than just financing publications. We know that they were

the ones that supplied the paper used in books, it would not seem that far-fetched

assuming that some of them also owned headpiece ornaments that would be used in their

books even if the printing was done elsewhere.

This paper serves as a proof of concept, demonstrating how book-historical and computational

approaches can be combined to study ornament reuse at scale. Although we have focused

on a large but still limited set of headpieces, our findings illustrate the promise

of uncovering more about the material practice of book production — especially the

interconnections among publishers in different locations and the artisans who carved

the woodblocks. Questions of production, distribution and the exchange of stylistic

influences between, for example, Irish and London actors, open rich avenues for further

research.

Our pilot study also lays the groundwork for a deeper investigation of the Tonson

publishing house, building on the ornament clusters presented here alongside other

evidence. If the name “Watts” was often absent from title pages, “Tonson” is also

elusive. By treating books as holistic objects — focusing on works, editions and all

relevant quantitative data — we can begin constructing a puzzle that has so far remained

unsolved. While we find the Tonson case especially intriguing, this is only one example

of how our scalable methods could be applied to other publishing enterprises, encouraging

further inquiry into the complexities of eighteenth-century book production.

Appendix

The appendix contains all manually annotated images referred in this paper by alphanumeric

codes or names, along with the metadata. The appendix can be found on the web with

this link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17035991.

Notes

[1] It is possible that the detection of reused headpieces is in fact reissue of

unsold sheets. We have not come across any instances of this in our examples. Books

with identical sheets could be easily detected in a future update to the methods.

[2] While ECCO is used as the source of image data, the bibliographic information

used as evidence for our findings comes from a cleaned and enhanced version of the

English Short-title Catalogue (ESTC), which in some cases has more detailed and accurate

information.

[3] This observation does not extend to near-variant headpieces designed to mimic

original books, which may arise from carvers distributing nearly identical headpieces

to various publishers and printers or, in instances of printing outside London, unlicensed

attempts to replicate the style of the original publications. Our evidence indicates

that these practices were prevalent, encompassing exclusive ornament usage, unauthorized

replication of headpieces, and the circulation of several near-identical ornament

copies, often without a deliberate pattern in their application.

Works Cited

Barchas 2003 Barchas, J. (2003) Graphic design, print culture, and the eighteenth-century novel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Belanger 1975 Belanger, T. (1975) “Booksellers’ trade sales, 1718–1768”, The Library, 5th Series, 30(4), pp. 281–302. Available at https://doi.org/10.1093/library/s5-XXX.4.281. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Benson 2010 Benson, C. (2010) “The Irish Trade”, in Suarez, M. and Turner, M. (eds.) The Cambridge history of the book in Britain, vol. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 366–382.

Bergel, Howe, and Windram 2014 Bergel, G., Howe, C., & Windram, H. (2014) “Lines of succession in an English ballad tradition: the publishing history and textual

descent of The Wandering Jew’s chronicle”, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 31(3), pp. 540–562. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqv003. (Accessed: 20 August 2025).

Bidwell 2010 Bidwell, J. (2010) The industrialization of the paper trade, in Suarez, SJ M. F., & Turner, M. L. (eds.) The Cambridge history of the book in Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 200–217. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521810173.010. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Chen et. al 2020 Chen, T. et al. (2020) “A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations”, in International conference on machine learning. PMLR, pp. 1597–1607. Available

at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2002.05709. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Chung et. al 2015 Chung, J. S. et al. (2015) “Re-presentations of art collections”,’ in Computer Vision - ECCV 2014 Workshops. Cham: Springer, pp. 85–100. Available

at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16178-5_6. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Dondi et. al 2020 Dondi, C. et al. (2020) “The use and reuse of printed illustrations in 15th-century Venetian editions”, in Dondi, C. (ed.) Printing r-evolution and society 1450–1500. Studi di storia.. Venice: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari – Digital Publishing, Fondazione Università Ca’ Foscari.

Available at: https://doi.org/10.30687/978-88-6969-332-8/030. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Dutta, Bergel, and Zisserman 2021 Dutta, A., Bergel, G. and Zisserman, A. (2021) “Visual analysis of chapbooks printed in Scotland”, in Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Historical Document Imaging

and Processing (HIP ’21). New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 1–6.

Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3476887.3476893 (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Feather 1987 Feather, J. (1987) “The publishers and the pirates: British copyright law in theory and practice, 1710-1775”, in Shevlin, E. F. (ed.) The history of the book in the west: 1700–1800. 1st edn. London: Routledge, pp. 5–32.

Foxon 1991 Foxon, D. (1991) Pope and the early eighteenth-century book trade. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Goulden 1988 Goulden, R. (1988) The ornament stock of Henry Woodfall, 1719–1747. A Preliminary Inventory Illustrated. The Bibliographical Society.

Harris 1996 Harris, M. (1996) “Paper pirates: the alternative book trade in mid-18th-century London”, in R. Myers and M. Harris (eds.) Fakes and frauds: varieties of deception in print and manuscript. 1st edn. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, pp. 47–70.

He et al. 2016 He, K. et al. (2016) “Deep residual learning for image recognition”, in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. IEEE, pp. 770-778. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Hu et al. 2015 Hu, B. et al. (2015) “Establishing the provenance of historical manuscripts with a novel distance measure”, Pattern Analysis and Applications, 18(2), pp. 313–331. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10044-013-0332-z. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Ijaz et al. 2019 Ijaz, A. et al. (2019) “Analytical Determination of Editions from Bibliographic metadata”, in Proceedings of the Research Data And Humanities (RDHUM) 2019 Conference: Data, Methods

And Tools. Oulu: University of Oulu, pp. 9-19.

Maslen 1973 Maslen, K. (1973) The Bowyer ornament stock. Oxford: Oxford Bibliographical Society.

Maslen 1993 Maslen, K. (1993) “George Faulkner and William Bowyer: the London connection”, Long Room, 38, pp. 20–30.

Maslen 2001 Maslen, K. (2001) Samuel Richardson of London, Printer: A study of his printing based on ornament use

and business accounts. Dunedin: University of Otago.

May 2019 May, J. E. (2019) “False and incomplete imprints in Swift’s Dublin, 1710–35”, in Bischof, J., Juhas, K., and Real, H. J. (eds.) Reading Swift: Papers from the Seventh Münster Symposium on Jonathan Swift. Leiden: Brill | Fink. Available at: https://doi.org/10.30965/9783846763971_005. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

McKerrow 1925 McKerrow, R. B. (1925) Fable of the bees [Book review]. The Library, 4(6), pp. 109–111.

Mosley 2009 Mosley, J. (2009) “The technologies of printing”, in Suarez, M. and Turner, M. (eds.) The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, vol. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 163–199.

Nguyen, Coustaty, and Ogier 2020 Nguyen, NV., Coustaty, M., and Ogier, JM. (2020) “An adaptive document recognition system for lettrines”, International Journal on Document Analysis and Recognition (IJDAR), 23, pp. 115 –128. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10032-019-00346-9. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Pollard 2000 Pollard, M. (2000) A dictionary of members of the Dublin book trade, 1550–1800. London: Bibliographical Society.

Ross 1990 Ross, J. C. (1990) Charles Ackers' ornament usage. Oxford: Oxford Bibliographical Society.

Rumbold 2020 Rumbold, V. (2020) Swift in print: Published texts in Dublin and London, 1691-1765. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ryan and Tolonen 2024 Ryan, Y., and Tolonen, M. (2024) “The evolution of Scottish enlightenment publishing”, The Historical Journal, 67(2), pp. 223–255. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X23000614. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Tolonen 2009 Tolonen, M. (2009) Self-love and self-liking in the moral and political thought of Bernard Mandeville

and David Hume [Doctoral dissertation, University of Helsinki].

Tolonen 2021 Tolonen, M. et al. (2021) “Examining the Early Modern Canon: The English Short Title Catalogue and Large-Scale

Patterns of Cultural Production”, in Baird, I. (ed.) Data Visualization in Enlightenment Literature and Culture. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 63–119. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54913-8_3. (Accessed: 20 August 2025).

Tolonen, Mäkelä, and Lahti 2022 Tolonen, M., Mäkelä, E., and Lahti, L. (2022) ‘The Anatomy of Eighteenth Century

Collections Online (ECCO)’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 56(1), pp. 95–123. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1353/ecs.2022.0060 (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Treadwell 1982 Treadwell, M. (1982) “London trade publishers, 1675–1720”, The Library, 6th Series, 4(2), pp. 99–134.

Uttama 2006 Uttama, S. et al. (2006) “Segmentation and retrieval of ancient graphic documents”, in Graphics Recognition. Ten Years Review and Future Perspectives. GREC 2005. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 3926. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp.

88–98. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/11767978_8. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Wang 2023 Wang, R. (2023) Visual element extraction and grouping from eighteenth-century books based on deep-learning

methods [Master’s thesis, University of Helsinki].

Wilkinson 2013 Wilkinson, H. (2013) “Printers’ flowers as evidence in the identification of unknown printers: Two examples

from 1715””, The Library, 14(1), pp. 70–79. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/library/14.1.70. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

Wilkinson, Briggs, and Gorissen 2021 Wilkinson, H., Briggs, J., and Gorissen, D. (2021) “Computer vision and the Cceation of a database of printers’ ornaments”, Digital Humanities Quarterly, 15(1). Available at: https://dhq.digitalhumanities.org/vol/15/1/000537/000537.html. (Accessed: 19 August 2025).