Abstract

Industry standard programming languages often leverage the English language for reserved

keywords – words interpreted as specific execution commands for the compiled program.

The Java programming language is no exception to using English reserved keywords,

and is used widely in industrial and educational settings.

The expert-novice programmer divide exemplifies an intriguing middle-ground for navigating

metaphor and highlighting polysemic interpretations of keywords. For experts, keywords

become “dead metaphor” (drawn from “career of metaphor” theory). That is, the expert

sees the keyword – often the entire grammatical construct with it – and derives programmatic

meaning near instantly. For the expert, there is rare consideration of alternative

English-language interpretations. Novices however, in attempting to first navigate

programming, may use these English keywords as familiar landmarks in unfamiliar terrain.

Amidst a sea of semicolons, single letter variables, and math operators, they may

gravitate to familiar words such as “if” or “while” to derive meaning.

Attempts by novices to create meaning using these English definitions can, however,

result in potential misconceptions. The word “for” as a preposition has over a dozen

distinct definitions. Which definition should a novice programmer use to achieve understanding

in learning to program, and what misconceptions may they develop through alternatives

to the “correct” choice? For some keywords, there may be no completely “correct” definition.

While this ambiguity can create a myriad of interpretations for critical code studies,

it can provide pitfalls for those first learning to program. This essay samples several

keyword interpretations that novice programmers may derive from the Java language’s

keywords and how polysemous meaning may affect their interpretation. Through observation

of students in their CS1 class, the author began exploring how polysemy, linguistics,

and metaphoric interpretations may affect understanding in beginner courses. These

students are largely native English speakers, highlighting that understanding rifts

exist even for native and colloquial speakers.

Code snippets are explored with both compiled keyword meanings and potential understood

meanings. This provides insight into pathways for student reasoning and navigation

in the programming landscape. The myriad of potential conclusions or definitions are

contrasted against the compiler’s singular interpretation, and how the polysemic potential

of natural language falls to singular dead metaphor in experts. This stark difference

between natural linguistics, critical code analysis, and compiled code meaning highlights

contrasts between programming and natural languages, in addition to highlight paradigm

shifts that may occur in pursuit of expertise.

1 – Strangers in a Strange Land: Novices at the Terminal

Learning to program a computer is not an easy task: we wave goodbye to the shores

of our analog realm, immersed in pools of strict digital logic. Novice programmers

often struggle to navigate this new terrain: with strange symbols punctuating supposed

sentences, and perplexing rules governing the effects of their efforts. When considering

the complexity of the novice’s first voyage into programming, it is little wonder

that syntactic keywords which appear as “real words," can become beacons they affix

their interpretations to.

1.1 Building Beacons: Core Concepts in this Essay’s Exploration

Before setting out, let us place a grounding keyword beacon for this essay. The term

“polysemy” suggests “\“the coexistence of many possible meanings for a word or phrase.” In this essay, polysemy refers to the concept of multiple interpretations used while

reasoning is at the forefront.

Polysemy naturally cohabitates with ambiguity: with many paths of interpretation before

us, which one will we choose? A word, a phrase, an idea, or a creative work may have

many meanings, exemplifying polysemy. This space for interpretation, for meaning-making,

is central to critical analysis and human creative endeavors. The beauty of ambiguity,

however, comes from a deep enough understanding to recognize and explore this ambiguity.

The interpretation of polysemy in critical code studies requires one to be able to

recognize a multitude of meanings within the text – to “walk each path” and consider

its destination.

This potential gives polysemy its poetic power, as seen in critical readings and literature

interpretations throughout human history. In pedagogical contexts, however, polysemy

can create tension. The intense novelty of learning new skills and information can

place pragmatic limits on our ability to appreciate polysemy. When learning how to do a task (reading or writing, for example) we focus on skill development and

tool mastery. Many pathways become an obstacle in this context: we cannot appreciate

“walking paths of meaning” when we are still achieving a baseline of the ground beneath

our feet.

Before we can craft new meaning – exploring complexity and abstraction, inviting novelty

– we must first understand how to wield what might be termed “original” or “intended”

meanings. We subvert and transcend through meaning making only through knowledge of

existing expectations and interpretations. As Critical Code Studies notes,

“As with all texts, the discovery and creation of meaning grow out of the act of reading

and interpretation” [

Marino 2020] – but this act of meaning making requires the skill of reading and the ability to

interpret what we have read to be present first. Through this work’s usage of the

term, polysemy may appear to be a negative to be “eradicated." This is not the intention:

it is a foundation of critical code studies and to creative analysis and exploration

of code. However, critical code studies rests on foundations of meaning-making

about and with code, which may consequently require “exploring pathways."

This challenge for novices learning to program is the crux of this paper.. Novices

often must first “resolve” on some level inherent polysemy in code – “choose a correct

path” – in order to conceptually understand programming. Once the task of programming

is understood, they may return and explore critically, recognizing and appreciating

the multitude of polysemic paths.

This essay explores specifically how the polysemy inherent in programming language

design through the use of English keywords can affect novice efforts to “make sense”

of coding as a practice. For instructors of novice programmers, language designers

seeking to create scaffolding for novice programmers to ease the barrier to entry,

or for those seeking to understand how novice programmers may interpret code throughout

the process of learning it, the question is how might this ambiguity be “resolved.”

The difficulties in polysemy “resolution” for novice learners should not be conflated

with critical analysis and interpretation. Where inherent polysemy can create challenges

on the path to learning, it creates potential and poetry by seeing code as a complex

cultural text in the hands of experts.

1.2 Mental Maps: How Do We Rationalize and Reason?

To better understand novice programmer engagement with syntactic keywords, it is vital

to consider the consistent perils they overcome while exploring learning to code.

Our investigation here of the novice’s journey begins with the concept of working

memory and chunks in order to build our theoretical framework on cognitive limits.

Expansion on these topics and their correlation to novice programming comprehension

can be found in the author’s dissertation [

Bettin 2020].

Neuro, cognitive, and learning sciences present evidence helping us better understand

novice programmers and the difficulty navigating digital landscapes. Novices develop

mental models of their environments, including the task of programming. Mental models

vary in size, complexity, and interconnectivity, but the summation of these models

and their connections form the cognitive basis of how we understand the world around

us [

Norman 1983]; [

Glynn 1994].

Learning to program can require developing many models. These may range from “how

a loop executes” to

“how the computer interprets programming instructions”, as well as connecting to other models, such as

“interpreting real world and word problems to solve using code”. Humans can possess multiple models of a single idea: interconnected models comprising

a theme (such as the interconnected “programming models” shown prior), fragmented

or partial models, and even distinctly different toggling models surrounding the same

idea to view a problem from new perspectives [

Norman 1983]; [

de Kleer and Seely Brown 1983]; [

Linder 1993]. Modeling is a foundational theory in human cognition, making it foundational to

understanding the process of learning to code.

Our mental models help us reason about the world and organize the vast quantity of

information in our minds. A complex problem becomes easier to solve when we recognize

component parts and their operational relationships. Understanding of those components

is built upon pre-existing mental models, which we use to reason about concepts like

potential action, reaction, and utility. When presented with problems so novel that

we are forced to reason intensely on each individual piece, our success in reasoning

suffers [

Anderson and Jeffries 1985]; [

Muller, Ginat, and Haberman 2007]; [

Vainio and Sajaniemi 2007]. In neuroscience, this lowered reasoning capability is largely correlated to working

memory – the area of our brain devoted to active problem reasoning. This area is fast

at reasoning about and retrieving relevant information but limited in the “space”

it has for this information. Folk science (in this case informed by neuroscientific

theory) suggests considering memory as 7 “plus or minus 2” chunks [

Miller 1956]. For a novice learning to program, the whole problem space is a novel area, and

each moving part can require distinct attention.

“Chunks” in working memory is useful for understanding the difficult task novice programmers

face. Mental model consolidation and organization helps to reduce the number of “chunks”

taken up in working memory, creating more space for ideas and reasoning processes.

If one is asked to remember the numbers “4 8 15 16 23 42," this would typically take

up six imagined “chunks” of memory to actively maintain these disjoint pieces of information.

However, if a fan of the TV show LOST is asked to recall “The Numbers” [

Lieber, Abrams, and Lindelof 2004] they might easily retrieve this information as one model, even after significant

time has passed from the remembrance task being given.

Mental models aid in meaning attribution through such consolidation, making complex

ideas and connections easier to access and retrieve. This leaves more working memory

for active reasoning tasks, like using those numbers to do calculations and recall

any necessary steps. Anyone who has repeated a phone number under their breath, or

counted out loud only to start over after a distraction, has first-hand experience

with working memory’s limitations. We only have so many “chunks” to devote to the

problem at hand, and when we cannot or have not developed a mental model for the problem

space yet, our ability to complete the task suffers as we struggle to juggle information

and reasoning with limited chunks [

Anderson and Jeffries 1985]; [

Muller, Ginat, and Haberman 2007]; [

Vainio and Sajaniemi 2007].

For the novice programmer, the nature of being a novice makes nearly every aspect

of the programming task new: they are indeed strangers in a strange land. Individual

lines of code are not even chunks – they are made up of chunks! Each element in that

line is a separate glyph they must reason about. To understand this further, let us

contrast the novice with the expert (or at least, more senior) programmer.

2 – Exploring Expertise: Chunking and the Career of Coding Metaphor

Where the novice sees each element as novel and distinct, experts see abstracted meaning.

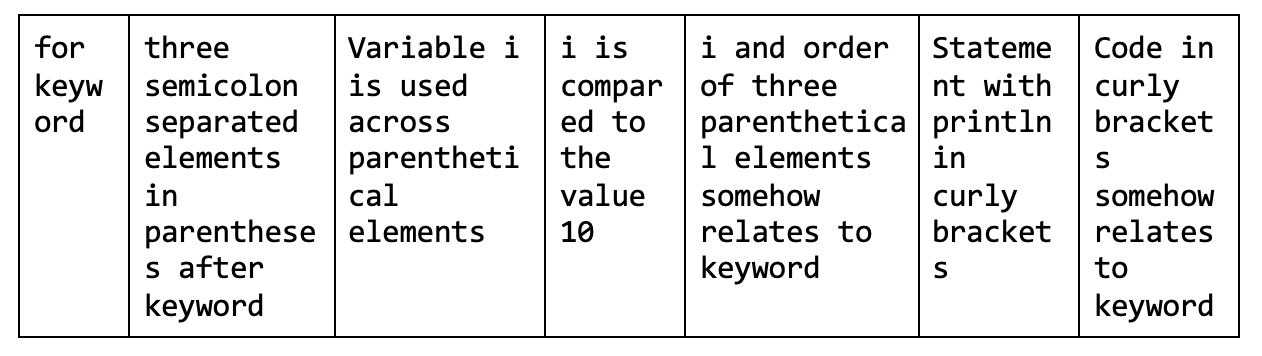

Quickly glance at this Java example snippet:

$$for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++){ System.out.println(i * i);}$$

If you have programmed before, what does the above mean to you?

Depending on your level of confidence or cursory glance speed, you may indicate something

high-level such as “it's a loop ”or “it repeats and prints something.” Perhaps you got more specific: “it prints the squares of the iterated values,” “it’s a loop that runs ten times,” or “the code prints the square of all values between 0 and 9.” You may have had confusion at first if you have programmed in another language which

uses the keyword “for” that is not Java, but you likely still arrived at an iteration-based

conclusion. Regardless of how you interpreted the snippet (though how one communicates

their interpretation is a viable critical code exploration in itself), your mental

model of programming informs that quickly reasoned abstraction: repetition is happening

in relation to numeric values.

For the novice, there are several potential barriers to that abstraction. Where experts

simply see “a for loop” as a single chunk, the novice is still reasoning about “what

a for loop is." Let us imagine for a moment working memory “chunks” as an array in

Java – a finitely sized grouping of elements. We will set our working memory array

to a length of seven elements and attempt to represent the contents. This is of course

a naive representation of our mental processes, but can help us understand the reasoning

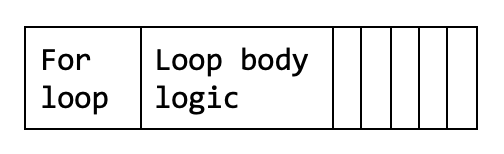

divide. The expert’s working memory in reviewing the snippet might currently be represented

as:

There is plenty of space for reasoning and “reconsolidating/collapsing” ideas. An

expert may use a chunk to consider the “iteration pattern” and reason about the executions

iterating variable i does, before reconsolidating that information back into the “for

loop” chunk to “free up space” again. Experts often do such reconsolidation without

recognizing any significant mental processing has even occurred!

On the other hand, the novice is still developing their model of what a loop is. Their

working memory looks much different. They reason about each component piece, trying

to recall distinct sets of instructions and rules for each piece to ascribe meaning

to the whole. For example:

The novice’s seven “chunks” are easily taken up in this example just assessing components

of the for-loop structure. They must then also reason about potential vocabulary words,

orders of operations, and use each element simultaneously in working memory to ascribe

meaning to the entire snippet in order to understand it. The novice is also likely

still assimilating prior topics, requiring additional resources to recall ideas still

being formed in mental models, such as variables or conditional comparison behavior.

This overload of working memory causes forgetting, mistakes, and slowed reasoning

as one attempts to make the problem space more manageable.

But

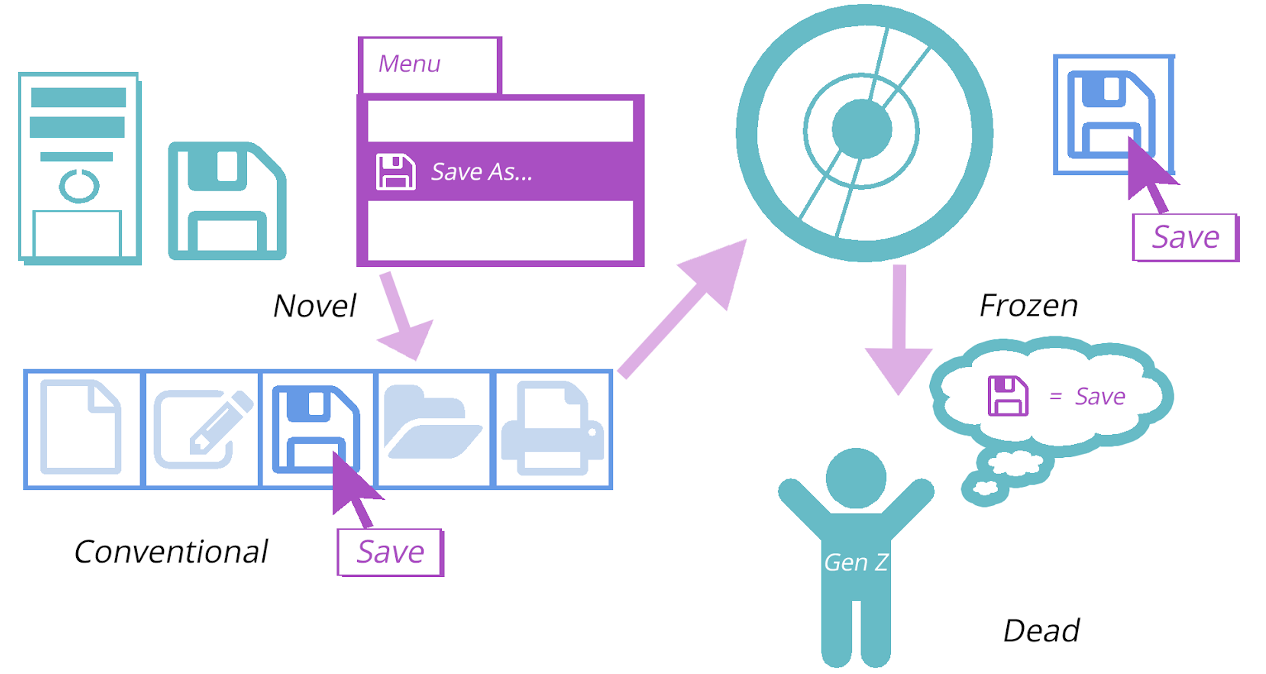

why do novices and experts reason so differently? Career of metaphor ([

Gentner and Bowdle 2008]) offers potential insight. Career of metaphor suggests metaphoric interpretation

undergoes four distinct phases: novel, conventional, frozen, and dead. “Novel” metaphor

is entirely new; we must actively work to create connections and attribute meaning.

As metaphor becomes “conventional," the concept and its metaphoric meaning is considered

alongside other ascribed meanings, normalizing the concept’s metaphoric associations.

“Frozen” metaphors are stuck in an intriguing historical state: their meaning is primarily

metaphoric, but the rationale underlying this metaphoric meaning is easily known and

reasoned about. “Dead” metaphors become purely associated with metaphoric meaning,

with their historic roots largely unknown or not considered in reasoning.

The original paper introduces career of metaphor’s progression using the term “blockbuster”

[

Gentner and Bowdle 2008]. Here, I use the concept of the “save” function on a computer. “Save” being associated

with a semiotic representation of a floppy disk was novel, requiring consideration

to associate the action and result (“clicking this button saves information to the

object that looks like this”). As the metaphor became conventionalized, one did not

need to “develop” the line of reasoning between why the floppy disk was a metaphor

for “Save” – it became implicit. As save functionality moved toward CD-ROM, USB, and

other forms, the icon of the floppy disk remained: exemplifying a “frozen” metaphor.

Many folks could still easily recall the original connection, but the iconography

was entirely metaphoric. Finally, Generation Z onward saw the floppy disk as a dead

metaphor, associating it only with/as the save icon. The metaphoric roots were not

relevant to understanding the representation: the floppy disk “is” the save icon.

Career of metaphor and expert coder behaviors suggest that code concepts and patterns

become frozen to dead-or-nearly-dead metaphor through repeated application and interpretation.

Concepts are novel as novices: one must create considerations and associations, developing

mental models of the idea. Through conventionalization and freezing, component parts

collapse into a semiotic metaphor of the code concept. Mental models then crystalize

to an intuitive and implicit, near-reactionary understanding of the meaning, giving

no indication of the building and meaning-making process along the way. The metaphor

dies: it is just a for loop, after all.

It is worth noting that “dead metaphor” does not denote that one cannot engage in

critical studies or analysis to revive and “remix." When indicating an expert believes

“it’s just a for loop," this denotes the ways in which expert mental models “rechunk”

a for loop as a singular element in order to better process the larger code problem

they are working with. One who engages in critical studies is inherently committing

to deeper analysis (and thus, more working memory devoted) to each portion, “reviving”

the pieces in mind in order to tinker, play, and critically consider their meaning.

One could parallel this difference as rote memorization of a poem and critical analysis

of its contents. While one who has memorized a poem may be capable of critically analyzing

it, they are not inherently engaging in that analysis each time they repeat it. However, their knowledge of the

subject matter is in part what affords them the ability to critically analyze it.

The same can be said for the expert: dead metaphor does not inherently mean the expert

cannot critically study code, but rather, in their “rote” daily activities, it may

not be necessary, and in those times, the code concepts remain dead metaphor.

3 – Landmarks in Learning: Keywords as Wayfinding

Novices navigating the complex coding environment and attempting to develop mental

models and schema are likely to engage in wayfinding behaviors to make sense of what

they see. The wayfinding process can help orientation in the strange programming landscape

through seeking recognized concepts. For many novices, one of the most salient wayfinders

are English language keywords. These elements are ascribed special meaning, associated

with some specific functionality in the programming language.

Gaps in “fitting” existing English words with strict programmatic intentions can create

pitfalls for novice programmers. As they seek out familiar elements in the unfamiliar

territory of programming, these recognized words are tangible waypoints. However,

they are expected to have one overarching intended meaning for problem-solving, but

possess myriad interpretations novices could arrive at.

These multitude of interpretations may create confusion about how code works. Programming

is

“a problem of mapping one culture onto another” ([

Arawjo 2020]), and sociocultural learning is

“a gradual appropriation of aspects of a specific culture” [

Haglund 2013]. When learning to program, novices reason not only about topics, but about norms

and representations of a new discipline, working to incorporate them into their mental

models.

Novices making novel metaphor connections to conventionalize programmatic understanding

may derive incorrect interpretations through the process, especially among words which

are already deeply polysemic. If keyword usage in programming and common parlance

differ, novices must develop an entirely new polysemic meaning and undergo the career

of metaphor process [

Gentner and Bowdle 2008]. Programming syntax precision compared to human language can easily necessitate

polysemous meaning for terms strictly based in “coding meaning" [

Krishnamurthi and Fisler 2019]. The keyword often serves here as a seemingly viable mid-step, creating programmatic

meaning for that word by considering

“the English use in a code context.” With English use understood, this can facilitate meaning-making in order to reduce

cognitive load. This behavior is by design: keywords were chosen because of this potential

transfer and relevance.

These existing definitions, however, can imply new or distinct meanings to novice

programmers which result in confusion while learning. Evidence for linguistic considerations

in programming language structure was shown in an empirical study which requested

participants identify the word they most associated with a behavior description. Perceived

intuitiveness of syntax words observably differed between programmers and non-programmers,

and specific terms such as “repeat” were more intuitive across populations [

Stefik and Siebert 2013]. Such lexicon issues also exist with words such as “document” and “save," which

behave as polysemic metaphor by connecting to analog equivalents, but typically have

a stricter meaning in technology contexts [

Forišek and Steinová]. Linguistic factors extend beyond the scope of syntax: they are embedded in the

design of technological vocabulary itself.

Through teaching novice computer science students, I have seen polysemic perils confuse

students still learning the programmatic paths before them. The power of words making

ideas tangible is a near-magical aspect of coding, but can be in conflict with the

narrow definitions these words hold to the compiler in programming. Investigating

these alternative meanings that may carry over provides an interesting linguistic

challenge for learners, programming instructors, and language developers.

3.1 Navigating Nuances: The Folly of ‘For’

The keyword “for” is inherently difficult due to its definition being highly context

dependent to its usage. To explore polysemy and its potential implications with regard

to learners, “for” is in a league of its own. Isolated, the word “for” as a wayfinding

tool is largely unhelpful due to its plethora of meanings – all of which are context-dependent.

Working with a student, one might attempt to explain this code snippet:

$$for(int i = 0; i < 10; i++){ System.out.println(i * i);}$$

To mean this:

Starting with an integer i that is equal to zero, continue repeating the code inside

the curly brackets while i is less than 10. Each time a repetition is over, increase

i by 1 before evaluating if i is still less than 10 again. The inside code calculates

and prints out i times i. This repeating loop starts at 0 and continues while i is

less than 10, with i increasing by 1 each time. That means this loop is going to print

out the values of all whole numbers from 0 to 9 squared.

Notice that in this description the word 'for' was never used. When one pauses beyond

rote syntax to ask: “where is the for in the for-loop?,” this keyword can easily begin to feel shoehorned in. We might say: “for i starting at 0, while i is less than 10...” but this does not provide any new or more specific meaning. The keyword 'for' is

lost in the weeds of additional, frankly strange-looking syntax. This strange syntax

and unhelpful keyword can lead students to believe a for-loop must be “fundamentally

different” than other loop types. Pedagogically, it is not: the looping condition

is identical to a “while” loop condition. The use of “for” does not suggest this,

nor does it provide any context on the additional syntax provided in this loop structure.

Historically, the use of the “for” keyword was introduced in ALGOL in 1958 (Wikipedia,

2022). Prior, “do” was the closest keyword match. The origin of “for” uses different

syntax than we see in Java and many other languages today:

$$FOR i = 0 (3) 99 BEGINPRINT (FL) = i END$$

Would print out in ALGOL each value of “i” starting at 0, changing by 3 each time,

and ending at 99. In this context, we might read it as: “for i starting at 0, incrementing by 3 and stopping at 99, print out i." This historical

context may shed some light on the keyword’s origins, but does little to help a novice

looking at the modern Java syntax make sense of the word choice today. Even in trying

to map the pieces, the ordering and function of elements has morphed as well: what

was once (base, step, end) is now (base, continue, step).

Merriam-Webster's dictionary provides two entries and eleven total definitions of

“for” (Merriam-Webster, 2020). Ten of these definitions apply to “for” as preposition

and one is a conjunctive version (this is excluding any prefix or suffix-based definitions).

This alone highlights the fluid, polysemic nature of “for” in natural language. Programming's

use of “for” to create understanding for novices captures none of that, often leading

to confusion as to “what it means” in the programming context. With “for” being a

context dependent word in English, only to become an independent syntactic keyword

in languages like Java, it is no wonder novice meaning-making gets lost in translation.

Uses of the word “for” in other modern programming languages – and even in other concepts

within Java – may only add to novice confusion. A “for each” loop (also called an

enhanced for loop) is another Java loop structure with a different syntactic pattern:

$$int[ ] a = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9};for (int i : a) { System.out.println(i*i);}$$

The above snippet uses the variable i not as an iterating numeric value, but as a

variable taking on the value of each element in an iterable set. With a created array of integer values named “a” prior to the

“for-each” loop containing the values i “took on” in the original for-loop, the “for-each”

loop presents the same keyword with new grammar as polysemic within the language itself.

The “for each” loop uses the same word to indicate instead “for each element in a,

let i represent that element, and do the actions within the loop body."

The “for each” loop is somewhat clarifying in that it “does some action (FOR) each

thing," but obfuscates even more what the word “for” as a keyword means, especially

in the original example. Novices cannot be blamed for wondering if “for” is always

an abbreviation of “for each” and thus arriving at misconceptions.

Exposure to additional programming languages can create murkier waters for understanding

“for." The MATLAB language’s “for” loops use an iterating numeric variable like Java’s,

but are syntactically more similar to Java’s “for each” loop. This can easily draw

confusion as two distinct concepts in Java are “blended” in MATLAB. In Snap! (a block

based graphical programming language), one block states the action “say for x seconds."

Here we see the syntactic keyword from Java – “for” – used as part of a natural language

command description! The use of “for” is not the same here: this block describes a

duration of real-world time, not programmer-controlled iteration. While it may seem

trivial, students first learning to program may relate these prior experiences when

encountering keywords across courses. They may arrive at unique and seemingly improbable

reasoning through polysemic blends of wayfinding and known meanings.

The “for” keyword highlights some of the rote expectations in learning programming

and why it can be difficult to understand what novices do not understand. Expert programmers,

through repetition, ingrain the strict representation of “what a for loop does” and

“how to set up a for loop." Experts internalize sentences like the one above, automatically

associating them to the representative code. Deeper investigation reveals that those

interpretations are not inherent – in fact, those mappings can be incredibly difficult.

The nuance of meanings within this word betrays its confusing nature. The ease with

which experts map keyword “meaning” outside of any syntactic evidence is a learned

skill, masking some of the difficulty English language presents in syntax. In fact,

this rote memorization and dead metaphoric relation can even cause inability to recognize

how this lexicon could pose obstacles at all.

3.2 Charting the Terrain: What’s This?

The keyword “this” in Java refers to the implicit parameter — the object calling an

instance method, “this object." For example, a Dog class:

public class Dog { }

Might be used to create Dog object variables in a program. The Dog class defines all

the properties and behaviors of Dog objects. I may wish to have the particular Dog

object, which is referencing the class, do an action or access as a variable. If the

Dog class defines some “play” behavior, I may wish to have “the Dog that is playing”

wag its tail. Within the play behavior, one could write: this.wagTail();

So when any dog object uses the play behavior, “that dog” will wag its tail.

$$Dog jake = new Dog(); jake.play();$$

The above creates a new Dog variable based on the class named “jake," and has “jake”

execute the play behavior (method). When “jake” does the play action, the Dog class

as a template is referenced for “how to do this action." The Dog class has no idea

what any variable may be named – programmers are able to name variables at their discretion.

The “this” keyword thus serves as a mirror reflecting “the object that called the

method” – in our case, “this” translates to “jake."

For novices, the keyword “this” and its function can be a source of confusion. Utilizing

“this” requires an understanding of object-oriented paradigm, which can be a major

shift from traditional ways of programming. Not only are students working to assimilate

meanings and models of various code concepts, but entire ways of thinking about “how

code is written” and “what code does” can be upended through object-oriented paradigms.

$$public Dog(String breed){ this.breed = breed;}$$

In the above example, the “this” keyword allows a demarcation to distinguish between

two variables of the same name. “this” refers to “This object” – the object calling

the constructor here in order to create a Dog object. Were I to reference creating

an object by indicating:

$$Dog ziggy = new Dog(“Doberman”);$$

“this” would refer to “ziggy” – this object, the object calling the constructor. Thus,

the code above can use the same variable name (breed) to refer to two different concepts

– the value passed to the constructor, and an instance variable of the object. “this.breed”

says THIS dog object’s “breed” variable, “ziggy’s variable”. The use “this”prior to

the variable name is here indicating use of an “ instance variable

$$private String breed;$$

But the class’s private variable is a distinct variable from “String breed” noted

in the constructor parameter list – despite having the same name. The implication

here is that “this.breed = breed” allows one to indicate “the Dog object calling this

constructor’s breed variable should be set equal to the breed variable in the parameter

list." In our case, “Doberman” was passed as argument to the parameter, and so ziggy’s

private breed variable would be set equal to “Doberman."

It can be difficult for novices to understand what “this” is, because “this” has the

potential to be any object! Tying to polysemic confusion, “this” typically refers

to an entity “close at hand or being indicated or experienced” (Merriam-Webster, 2021).

Novice programmers often write code to solve a specific problem, yet the “this” keyword

requires grappling with potential futures and objects which may not exist yet. When

considered from the extensible program design angle, “this” in programming is almost

at odds with its vocabulary definition. Novices know the name of variables “close

at hand” in their program – they created them. “Why not just call them by name? What is the point of “this”?” These questions encapsulate difficulty with an object-oriented paradigm shift, one

the “this” keyword’s polysemy does not initially help novices mitigate, given their

proximity to their own code files.

Novice programmers, in not understanding extensible design yet, may attempt the following

in writing their classes:

$$public Dog(String breed){ ziggy.setBreed(breed); }$$

In the above example, the novice is attempting to use the variable name they know

(“ziggy”) in place of “this." However, this makes the constructor only ever modify

ziggy, despite a constructor being called in order to construct new Dog objects. Thus

if the student then writes:

$$Dog wishbone = new Dog(“Jack Russell Terrier”);$$

When the constructor is called to create “wishbone," “ziggy” will be modified to be

a Jack Russell terrier, and no variables will be set for wishbone. Further, this code

will only function without error if the students are in fact creating their Dog objects

in the Dog class itself. Consider when Dogs are created in a “DogPark” class for

example that exists in the same project:

$$public class DogPark(){ public static void main(String[] args){ Dog ziggy

= new Dog(“Doberman”); Dog wishbone = new Dog(“Jack Russell Terrier”);

}}$$

The novice’s attempts simply will not function, as the Dog objects are out of scope

in the Dog class, and thus, attempting to call those object’s variable names within

that scope will give errors. This is often a source of confusion: “I made my Dog variable,

and I change the breed, why doesn’t the code recognize the variable?”

While the above examples of “avoiding” this might seem strange to an expert, they

are reasonable for the novice who is first grappling with extensible class design.

The concept of classes as “templates," which may derive many different variables,

is removed from a “step by step” paradigm that many novices are first introduced to.

The avoidance of “this” is rooted in confusion surrounding extensible object-oriented

programming for the first time. However, as novices begin to unravel extensible object-based

paradigms, “this” can reverse from confusing to clarifying. The trouble often lies

in novices needing to use “this” to navigate object-oriented design in the first place

(as shown above to change the Dog breed), creating a chicken-and-egg scenario.

3.3 Pondering Paths: Other Examples of Polysemy Play and Syntax Specifics

3.3.1 – Final : The “final” keyword in Java denotes variables which have an unchanging value. The

value is “finalized."

final double PI = 3.14159;

The above means the variable “PI," which is of type double, cannot be changed from

its final value of 3.14159. However, the word “final” can often indicate completion

of something that was previously able to change. In Java, “final” must be stated during

declaration when the variable’s name and type are defined. Simply: one must know a

variable is going to be “final” when the variable is created, so it will only ever

have that one value. Java has no process for the variable to take on different values

before achieving the “final” value. We cannot do calculations and then “arrive” at

the final value. The variable starts as, and always is, final.

Other languages use the keyword “constant” or “const” to represent the concept of

“final” in Java. “Constant” describes a persistent state of being in the same form,

which is much more aligned to the expected behavior in Java. Though better, “constant”

is not perfect, as it may introduce new polysemic confusion, such as a variable being

“constantly” available similar to how a “public” variable might be. Java’s use of

“final” introduces potential new ideas and interpretations for how the code is allowed

to execute due to the keyword’s existing meaning. This polysemy when used in wayfinding

may lead to misconceived notions.

3.3.2 – Static : Methods (functionality or actions; sometimes called functions, tasks,

or sub procedures in other languages) that do not return a value use the keyword “void”

as their return type in Java. “Void” indicates to be “empty or without something,"

but can also mean “absence of” or “lacking." Novices can struggle to recognize void

methods can still have “value” in their actions, even if they cannot return a value

back. A novice may question “why they would ever write a void method," believing these

methods are without any value of use. This case of polysemy obstructing understanding is rather amusing,

as most applications in Java require the following method in order to encapsulate

the runnable code:

public static void main(String[] args) { }

Novices are clearly aware this method “has value," as without it they cannot run their

code. When writing their own custom methods, however, they can struggle with void’s

meaning in context, and see the value of “methods that aren’t main” as only being

“to send stuff back." Methods promote consolidation and meaning-making in programs,

allowing statements that have meaning to be bundled together and clarified with a

name used to activate those statements.

One may also question if novices draw to mind the “not valid” definition of “void,"

such as when a check or contract is voided. They may believe that writing “void” negates

their method and makes it unusable in some way, thereby rendering it to have “no value."

This definition of void is one of the more common “daily life” uses, and thus would

be a reasonable polysemic connection for a novice to make.

3.3.3 – Continue and Break : There are many cases where a keyword’s definition-based meaning may be clear, but

its intended usage in a “code sentence” is not. Keyword “continue” for example might

be interpreted to mean “continue on to the next statement” not “continue on to the

next loop iteration":

$$while (true){ continue; System.out.println(“Hello”);}$$

The expert might question in this example how one could read “continue” as meaning

“move to the next statement” as it would be trivial. They would question writing a

loop that infinitely checks its condition then continue to the next iteration while

never printing anything. For a novice investigating code examples for the first time,

however, continue may look like a “permission” statement. They may believe “continue”

is required in loops to move forward to the body when the condition is true. If one

has not learned the specific intended meaning in programming, an assumption like this

can form and subsequently strange code artifacts can result. A novice may similarly

believe interpretations such as “break” meaning “to break out of the program, to stop

immediately” rather than “to leave the current iteration of the loop." Novices have

written code snippets not unlike the following:

$$while(x < 10) { //some changes are being made to x here if (x == 12){

break; }}System.out.println(“Program complete”);$$

If a novice interprets “break” as “break out of the program”, then they do not believe

“Program complete” will print out at all if x is equal to 12 in the loop. Instead,

12 is seen as a special exit case which terminates the program early.

4 – Monuments with Petrified Purpose: Assimilation to the Unbending Compiler

Often, novice programmers are making a good faith effort to communicate programmatic

ideas – not unlike a traveler making a good faith effort to speak local languages

or dialects. However, where locals often also make an effort to understand speakers

with weak language skills, the computer makes no such effort – because it cannot.

The computer is viewed as an intelligent but suspicious conversation partner. We trust

a computational conversation partner is “telling the truth” in terms of its actions,

but often do not “trust” it. Uncanny valley, fear of automation, and further digital

phenomena point to value acknowledgement but scrutinizing uncertainty by humans. Programming

can compound this preconception.

Perceiving the computer as knowledgeable but not trustworthy only exacerbates efforts

by technologists to build stronger support into the programming conversation. When

programs like Microsoft Word attempt to aid users with formatting – trying to “converse”

with users knowledgeable about writing – it can be seen as patronizing, intrusive,

and annoying. When programming environments with “intelli-sense” such as Eclipse or

IntelliJ attempt to help novices correct mistakes through in-application feedback,

the “knowledgeable” preconception overrides other characteristics. The novice programmer

sees the computer as expert in matters of computational language, taking its suggestions

without critical analysis or discourse.

While novices in all fields often defer to experts as truth tellers, the preconceptions

of the computer add a new layer. Conversations become one-sided, with programming

software intended to help appearing to “state facts” rather than providing feedback

for critical analysis. This causes additional issues that the “truthful” nature of

human experts does not. The compiler does not have context for intention: it parses,

translates, and derives meaning only from what it sees within the coded communication.

Human experts may say something confusing, leading novices to an incorrect assumption.

However, human experts have contextual information allowing them to revise their responses

and effectively deliver their expertise. Compilers, intelli-sense, and such can only

revise within their parsing and capacity to interpret that parsing. We communicate,

but the program has limited bounds to understand that communication. And unlike natural

language, we cannot shift our linguistic style or add additional explanations in the

same way to bridge understanding. We are communicating, but not in the way we as humans

are conditioned to expect.

New keywords, strange structures, and a lack of guidance on why it was suggested to

“put that element there” can lead to novice reasoning attempts which manipulate the

polysemy of keywords in ways that lead to incorrect conclusions. In learning object-oriented

paradigms, students may often struggle with the “static” keyword’s use (or lack of)

in Java. A non-static method is one an object uses, and what students learning object-oriented

paradigms should be creating. However, if they struggle to invoke their non-static

methods, the development environment often suggests converting the method to static

in an attempt to “resolve the issue." The “knowledgeable” computer is “the expert,"

and the student implements the suggestion, but the program is no longer object-oriented.

The compiler has communicated an illogical suggestion for the problem at hand, and

the student, working still to develop and recall meaning, does not know better. The

student may make assumptions about static methods based on these suggestions, because

their code now “works." In attempting to understand the word “static” as a bridge

to their problem’s “solution," they may create entirely new meanings and subsequently,

new models justifying this coded behavior.

Even when programmers become capable of reviewing compiler and development environment

suggestions as feedback to be analyzed, the conversation falls short beyond that point.

They are now engaged in critical analysis, but the compiler can only help begin that

process – it is not a conversational partner through it. More expert programmers know

that this programmatic feedback should become an exercise in analysis and consideration.

But once the computer opens the conversation, it promptly becomes ill equipped to

engage in it! Debugging approaches allow the computer to facilitate and become part

of the process, but the programmer develops the analysis and discourse within their

own mind. The conversation partner is not really a partner at this point – the concept

of communication has shifted at the exact point that strong communication is desirable.

4.1 Lost in Translation: The Novice-Expert-Compiler Fault Lines

Novice programmers face a daunting task in learning to program. They create mental

models of an entirely new way of reasoning, symbols and grammars within that reasoning,

and translating ideas across native spoken/written languages to programming ones.

The nature of this learning can become more difficult due to expert-novice gaps and

compiler-programmer relationships.

To simply see “a for loop” and intuitively understand its meaning is to have navigated

the career of metaphor and created meaning for the entire code concept. To grok the

concept in this way moves past polysemic keyword wayfinding (and often even component

part acknowledgement) into a built model which identifies the entire code concept

as a monolithic metaphoric representation.

These monolithic metaphors can be seen as dead-or-nearly-dead clearly through the

struggle of those who “know programming” to tangle out how they arrived at them. Frustration

takes root as experts try desperately to point out what the code, to them, definitively

is: “it’s just a for loop, that’s what it does!” The novice, working to learn and create these associations, cannot appreciate this

dead metaphor. They are grappling with the novelty and connection making of so many

smaller chunks to build this larger metaphoric model. Their difficulties with polysemic

keyword interpretation make no sense to the expert, so removed from reasoning about

the concept at that level that they cannot separate the parts from the whole. Many

struggles in teaching and peer learning activities stem from communication gaps. Several

of these gaps are likely attributed to distinct levels of mental model changing what

metaphoric interpretation is occurring.

4.2 Back to Square One: Novices as Experts, then Novices Yet Again

Given the potential confusion and obstacles, it may be a wonder that novices become

expert programmers at all. Novices are resilient, and our mental models adapt through

critique and challenges [

de Kleer and Seely Brown 1983]. As novices encounter situations which conflict with the polysemic “meaning making”

they have arrived at, critique and revision promotes development toward understanding

“how code works." Novices engage with programming culture and the digital landscape,

growing more familiar with programming norms. Repeated exposure and practice further

develop their models, freeing working memory and allowing them to reason more about

the semiotic meaning of keywords.

Experts are not strictly confined to dead metaphors either. As keywords are used in

new contexts, experts often leverage the same heuristic wayfinding to English meaning

that novices use. Experts may use this in conjunction with what they “already know

about code," attempting to critique and expand their model further. Experts also extend

this heuristic commonly in another direction: they may see common keywords as dead

metaphors, but make assumptions about the behavior of non-keyword functionality given

its naming convention. Method names are intended to reveal expected behavior such

as “hasNextLine” determining if another line of text exists for a Scanner object to

read. An expert may make assumptions or have skewed perspective in interpreting a

method’s intention as they create polysemic associations between the functionality

name and the functionality they imagine a need for. Just as novices become experts

through repetition, so too do experts in new environments and novel situations often

return to this novice wayfinding tendency.

Circling back to our beginnings, experts may once again break free from dead metaphor

to interrogate the power of polysemy through critical code studies explorations. With

“dead metaphor” understanding in hand, reflection, analysis, and questioning may allow

for more interpretations and new views of “old, dead” code as a cultural text to make

new meaning from and with.

5 – Markings Meant for More: Towards Polysemic Programming Futures for All

Programming expresses problem solutions using specific grammars, definitions, and

structures. These methods of expression are referred to as programming “languages,"

further driving implications of communication. This creates a paradox of polysemy

for novices at the onset. Where natural language is malleable and able to shift with

culture, programming’s current form requires rigid ascribed meanings for compiler

translation. We can (and do) develop high level languages, intelli-sense, and other

features attempting to bridge divides. Still, our programs are currently bound by

the need for the compiler to execute them. And the compiler, unlike humans, does not

have an ability to contextually interpret, shift linguistic patterns, accommodate

communication levels for conversation participants, and so on.

Humans do these things in conversation. Machines, presently, cannot.

Learning to program requires mapping new concepts, environments, and vocabularies:

metaphoric ideas are woven into the representations within computer systems, such

as icons, application designs, and commands [

Wozny 1989]. Computation’s language is largely borrowed, and the discipline of computer science

consistently creates its own subject matter, a novelty among disciplines [

Colburn and Shute 2008]. The metaphors within programming contexts create comfortable analogs to non-programming,

“known” landscapes, such as the English language or physical objects. These analogs

can help us navigate these strange spaces – to make sense of novel terrain through

footholds in the familiar. They may even promote creative comparison of programming

to other disciplines, and of course in the hands of experts, these metaphors can spark

creative critical code analysis leading to new forms of meaning making. Despite these

benefits of metaphor creating pathways and connections in meaning making, we are ultimately

expected to engage with concepts, systems, and vocabularies in a specific way as novice

learners to navigate “how to code."

While programming keywords rely heavily on polysemic meaning, their compiled interpretation

is rigid and unrelenting, at odds with the flexibility and context of natural language.

However, as a discipline that invents itself, programming can imagine new and different

futures for its languages. New language development may: center and employ different

design approaches, consider implications and potential meaning-making before choosing

keywords, and explore the pitfalls and poetic power that keywords may present. New

compiler and integrated development technologies could scaffold “context creation,"

to create more relevant dialogues between the programmer and the technology, aiding

model development and communication. Integrated development tools could help novices

interrogate polysemy, indicating when a programmer may be applying a definition at

odds with expected compilation behavior. Languages taking on new paradigms and characteristics

may also allow for greater polysemic meaning making and new ways of creating programming

metaphor, such as Jon Corbett’s morphemic language structure in Cree# [

Corbett and Temkin 2021].

While polysemy may be an initial hurdle for the novice, moving past these initial

hurdles into expertise allows them to reopen this world of metaphoric meaning as a

design instrument in their code. However, to get there they must first narrow their

view of meaning to

“what will happen during execution” before they can fan out again. Natural language and culture are nuanced and dynamic,

but programming keywords compile rigidly and single-mindedly. Metaphorical and situational

reasoning, including the process of polysemy, are core aspects of our cognition, meaning-making,

and subsequent modeling of the world [

Gick and Holyoak 1980]; [

Gentner 1983]. As programming moves forward, let us hope for languages and tools that foster greater

communication and understanding, allowing novices to create enough meaning of programming

to become experts able to themselves engage in the subversive and cultural meaning-making

of critical code studies.