Introduction

In this essay we explore the relationship between code and the physical world by examining

a media artifact that, we contend, challenges some common assumptions about this relationship.

We wish, in particular, to challenge the preconceived notion of a strong dichotomy

between code and external world: that code is the result of an encoding, a translating

of some aspect of the physical world into a discrete symbolic system that, when executed

on computational hardware, follows its own rules. Code is commonly, if implicitly,

represented as an interiority intimately intertwined with, but ontologically and pragmatically

delineated from the exterior, analog environment. In this model, computational hardware

bridges the gap between these two worlds — between, that is, the symbolic representation

and what it accomplishes, the digital and the analog. In what follows we interrogate

this formulation, as well as the attendant assumption that code must always be digital,

by examining a unique and culturally significant example of a video game: Volleyball, coded for the first home video game console, the Magnavox Odyssey. The Odyssey

was developed from 1966 to 1969 by Ralph Baer and a small engineering team at Sanders

Associates and released by Magnavox in 1972. Unlike nearly every other video game

console released since, the Odyssey lacked a microprocessor: its internal signals

were continuously variable voltages, not quantized bits. While this categorizes it

as an analog device, in what follows we argue that its analog architecture does not

preclude it from possessing digital logic, nor from being programmable. Situating

the Odyssey within the historically significant, but academically under-examined tradition

of analog computing, our purpose is threefold: First, we wish to draw attention in

critical code studies to the tradition of analog computing, offering an examination

of many parallels between digital and analog programming. Second, we explore the

unique affordances of the Odyssey as a programmable platform that integrates logic

and material structures in a unique and historically important way. Finally, we argue

throughout for an expanded concept of code and coding that challenges the centrality

of the digital and more expansively engages the roles of users and physical environments

as components of coded systems.

The Odyssey came bundled with twelve games and many insertable game cards, television

overlays, decks of cards, game boards, and other “playing aids” that supplemented

the on-screen graphics, and which are necessary to fully constitute the games. Shortly

after launch, a collection of six additional games was released to the public through

Magnavox retailers as an add-on purchase for Odyssey owners.

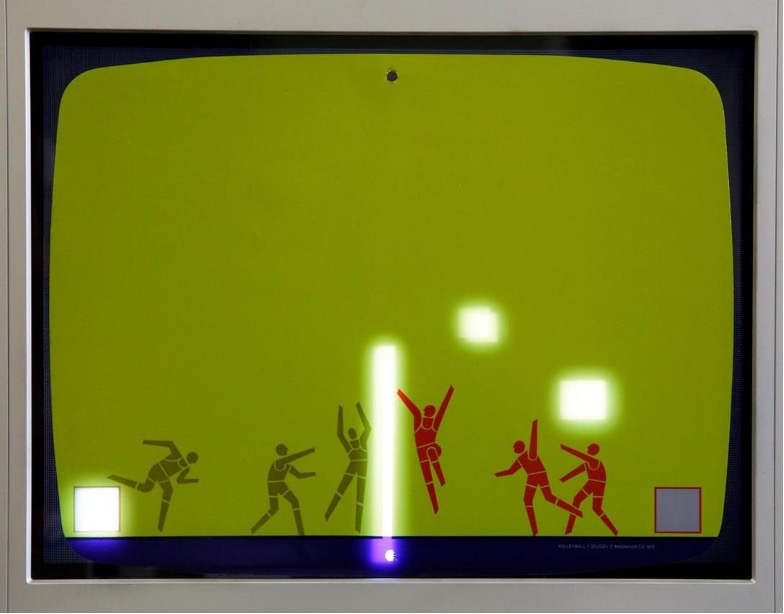

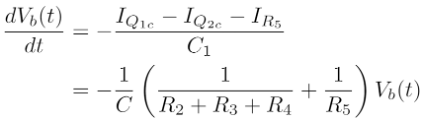

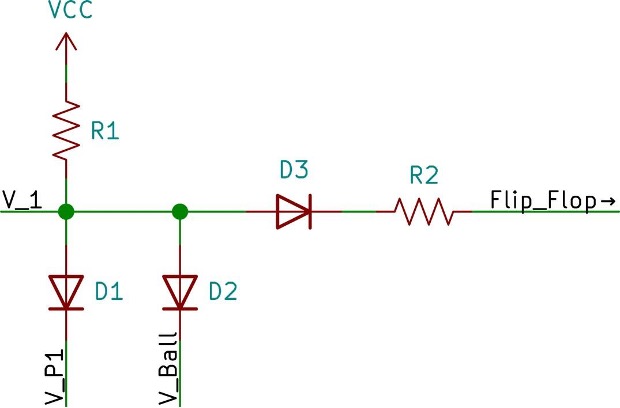

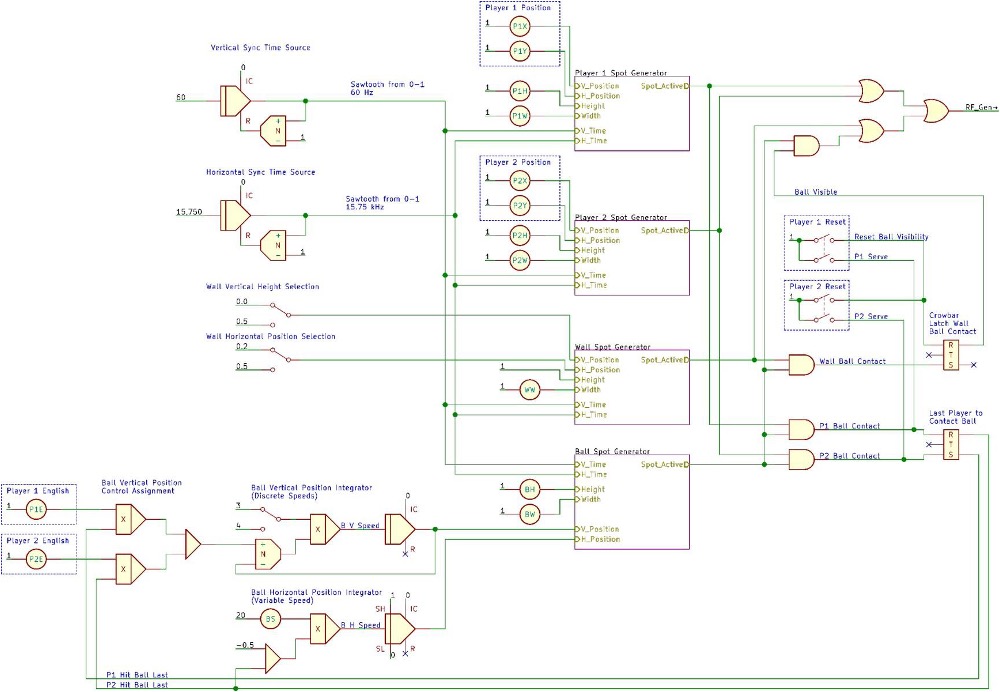

Volleyball, the specific program we analyze here (Figure 1), was one of those six add-on games.

[1]

It was commercially released in its own product box packaged with a game card (#7),

an instruction sheet, and an overlay in two sizes (for 19” and 26” televisions).

Like almost all other Odyssey games,

Volleyball requires the players to place a thin plastic overlay over their television screen

to provide additional (static) graphics for the on-screen environment and to produce

various optical effects such as altering the color of the television’s graphics, hiding

them with opaque layers, or brightening them with clear sections.

Volleyball’s overlay is relatively simple, composed of a single color background, serve locations,

net location, and images of volleyball players in action (Figure 1). Judged by number

of components, this was the sparest game in the pack. We’ve chosen to analyze this

particular game not because it was especially popular or influential, but because

it is representative of analog programming at the time, makes use of many of the Odyssey’s

capabilities, and possesses a number of unique features that we consider particularly

illuminating of both the differences and intertwining between analog and digital systems

In particular,

Volleyball is a useful object with which to explore the gap between the simulation produced

by coded games and the actual milieus and processes to which they refer.

In order to explore the relations between code and world, staged by Volleyball and the Odyssey, we will consider and demonstrate several symbolic schemas for representing

the game’s code, each illuminating a different “level” of operation, scale, and abstraction.

First, we examine the Odyssey’s hardware, in which much of its digital logic and analog

computation is encoded as a series of circuits and flows. Second, we consider Volleyball’s code as a series of mathematical functions that link hardware to symbolic operations.

Third, we demonstrate the logic flow layer of the program using analog computation

notation (“program blocks”) and compare this to coding in today’s digital programming

languages. Finally, we consider elements of the game’s algorithm that are addressed

directly to players and require various real-world bodies, objects, and interfaces

to fully run the program’s main loop. Along the way we examine the affordances of

each symbolic system and ontological layer for revealing meaning in the code, as well

as the limitations of each.

We hope that this discussion will also serve as a primer on the nearly forgotten media

ecology of analog computation and programming. We argue that Volleyball “plays in the gap” between simulation and reality, digital and analog, code and world,

and thereby provides us with an exciting object with which to think through not only

the historical birth of home video games (as precursor to home computing), but also

the material affordances and transitive capacities of all code, analog or digital.

This examination of an Odyssey game will lead us to a characterization of its programming

as assemblage-making —a kind of code that runs on different levels simultaneously,

accepts feedback from their unique properties, and composes new channels for communication

between levels. We hope that this vision of code as material, multiscalar, and porous

what we call multi-level coding, will inspire programmers to explore similar modalities

in the future.

Level 1: Hardware

Hardware, or an active substrate capable of running code, must be able to receive

signals, transform them in accordance with their content, and usually produce some

sort of output, either digital (such as a string of serial data) or analog (such as

light emitted from a screen or sound emitted from a speaker). Media theorist Friedrich

Kittler, in his notorious essay, “There is No Software,” notes that “all code operations,

despite such metaphoric faculties as call or return, come down to absolutely local

string manipulations, that is, I am afraid, to signifiers of voltage differences”

[

Kittler 1997, 150]. In Kittler’s formulation, code functions culturally to conceal its own signification,

to “obscure hardware with software,” a kind of conjuring trick pulled off through

the stacking of many “interfaces between formal and everyday languages” [

Kittler 1997, 150]. If code’s actual signifieds are physical state changes, software misdirects

its human users to invest meaning elsewhere, in an abstract, symbolic space. This

seems to disturb Kittler because code pretends to a universality (a Turing machine)

that subsumes and transcends the physical world when in fact it engages only a small

portion of it: that which is programmable using discretized hardware configurations.

Kittler goes on to argue that nonprogrammable systems (continuous or analog structures

such as “waves,” “wars,” and “beings”) are not only more characteristic of “the world,”

but also far more dynamic in connectivity and growth. Code, he implies, is inadequate

to represent or capture such processes because it is functionally limited by the discrete

hardware to which it reduces, and “only computations done on nonprogrammable machines

could keep up with (the continuous systems of the world).” Kittler’s argument is

more nuanced (and perhaps beguiling) than is usually acknowledged, or indeed that

his essay’s polemic title would suggest. While there are a number of ways to answer

(or dismiss) his claims, we would like to explore them in a novel way by examining

code that performs its computations on precisely the sort of “nonprogrammable machine”

that Kittler seems to rule out: the Magnavox Odyssey, a platform whose physical substrate

is fundamentally continuous, or analog, rather than discrete, or digital.

The Odyssey is not constructed out of silicon chips that quantize voltages in on-off

gates at discrete times. Rather, it consists of an electrically conductive set of

nested circuits that elicit continuous and discontinuous waves and modulate these

signals at every moment, thus retaining their continuous (analog) nature. Nonetheless,

it processes sets of instructions that deftly weave digital logic with continuous

processes by converting between the two internally and providing output signals that

retain both characters. A fully digital computer can, through numerical integration,

analog-to-digital converters, and digital-to-analog converters, approximate behavior

of analog systems; yet as Kittler and audiophiles who shun digital formats for vinyl

have long argued, approximation is not ontology, and what is at stake is being, or

presence, itself.

The Odyssey is, at its hardware level, an analog device, and yet it is programmable.

As such, it is a member of a class of devices once significantly more common than

digital computers, yet contemporaneous with them: the electronic analog computer.

The general neglect of analog computers, by both popular culture and scholars, is

perhaps at least partially attributable to a “progress narrative” constructed by the

nascent digital computer industry in the 1950s for marketing purposes, which was enthusiastically

taken up by the popular press of the time. This discourse suggested, contrary to

professional discourse, that digital computers were superior successors to analog

computers rather than contemporaneous machines suited to different sorts of tasks

[

Kline 2019]. Part of the allure of the digital machines was that they seemed analogous to brains

and were in fact usually called “electronic brains.” The analog computer, as we will

see, functions by programming dynamic systems that were analogous to those about which

they computed. Ironically, then, their greater analogic flexibility rendered them

narratively less sensational than digital computers, with their single striking analogy.

This asymmetric popular coverage has been inherited by scholars today. Another discursive

trend has also served to diminish the historical visibility of analog computing, and

that is our contemporary popular characterization of code. Code captures the imagination

because it is expressed in linguistic terms, yet opens a communications channel to

complex machines. In the popular conception, code is associated with digital computing

only. We are, in this article, attempting to correct both the historical elision

that led to the misconception that only digital platforms are coded systems.

The first modern electronic analog computer, the special purpose “Polyphemus,” was

invented in 1938 by George Philbrick, then refined into general purpose versions in

Germany and the USA during World War II [

Holst and George 1982, 144]; [

Ulmann 2019, 1763]. Electronic analog computers use electricity as an “analog” or dynamic model

of real world systems being studied (such as planetary motion, economic behavior,

stresses on bridges, and the aerodynamic performance of aircraft designs). As one

popular guide to analog computing from 1952 puts it:

In these devices physical quantities, such as voltages and shaft rotations, are made

to obey mathematical relations comparable to those of the original problem. The physical

quantities, or machine variables, which may be conveniently varied and measured in

the laboratory, must, then, behave in a manner analogous to that of the original variables”

[Korn and Korn 1952, 2].

In the case of electronic analog computers, electricity itself was the analogous substrate

employed. Users would program the computers to mimic the behaviors of the systems

they wished to study and then input variables to compute how the system would behave.

Until about 1970, analog computers were significantly cheaper, smaller, and faster

than digital computers and saw widespread use in business, government, and universities

[

Korn and Korn 1952, 2]; [

Gilliland 1967, 1–1]. We’ll explore the analog computer further in the following sections as we

follow

Volleyball’s code up to higher and higher levels of abstraction. First, however, we must take

a look at the Odyssey, which we will regard as a special purpose electronic analog

computer.

The Odyssey’s prototypes were developed by a team of engineers led by Ralph Baer at

U.S. defense contractor Sanders Associates from 1966 to 1969 [

Baer 2005]. Because the console was designed to play real-time interactive games and remain

inexpensive enough to be released as a consumer product, the use of analog computing

circuitry was a logical choice: not only were the engineers at Sanders extremely familiar

with such implementations, but analog computers’ speed of operation suited the real-time

gameplay that Baer desired.

[2]

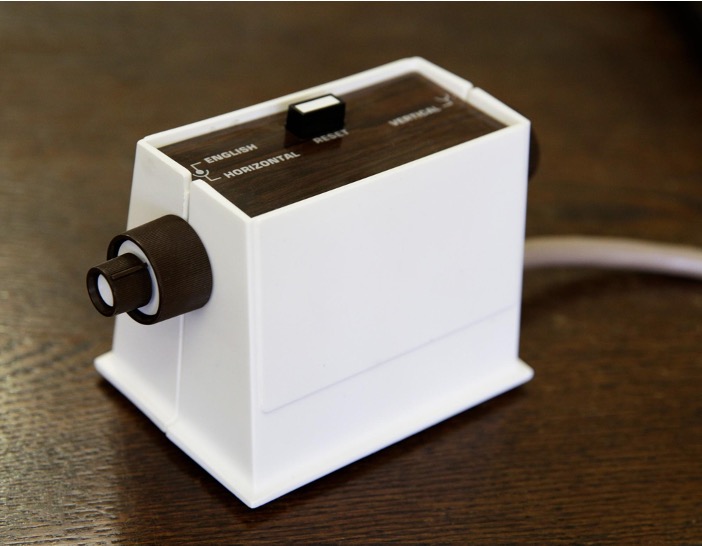

Baer’s “TV Games” console, however, would be custom built to dramatically reduce the

cost and complexity of the device, eliminating all circuitry that didn’t serve to

enable the suite of games imagined by its engineering team. Nonetheless, despite

its limited internal circuitry, the Odyssey prototypes retained a high degree of user

programmability via a bank of switches that served to re-route the internal circuits

to produce many different possible machine states, or analogs of physical behavior.

Magnavox engineers, as they refined the design from 1970 to 1972, replaced this interface

with a card-based system. Programs were pre-manufactured into circuit board based

“game cards” that were then inserted into a slot in the console. Each card contained

44 pins that could be interconnected in numerous different ways. Thus, the end user

need only insert the proper numbered card to load a particular program. This design

proved highly influential in the home console industry that the Odyssey spawned.

The game

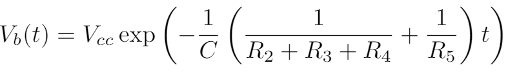

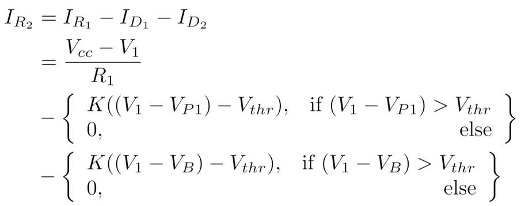

Volleyball that we are analyzing here used game card #7 (Figure 2).

Internal Odyssey circuitry uses a nominally 5.6V single ended power supply. Its circuitry

is organized into ten modules (circuit boards) that take the form of removable “daughter”

cards plugged into slots on the Odyssey motherboard. Signals are passed from daughter

card to daughter card in a variety of ways including analog and digital signals. The

motherboard mostly consists of direct connections between daughter cards. However,

it also contains circuitry for adjusting spot size, wall size, ball speed, a latch

circuit (“crowbar”), and an RF modulator to encode its video signal into the format

required by consumer televisions of the period. In Level 2, we will discuss specific

sub-circuits within the Odyssey and the differential equations that describe them.

In today’s digital computers, electrical components on motherboards are used to condition

electrical current to power various devices (from processors to amplifiers to LCD

arrays) or to carry digital signals from one processor or memory bank to another.

In analog computers, electrical components become the processors themselves: by altering

the current or voltage of electricity within their circuits over time, they alter

the information contained in those flows. Each banal electrical component, then, becomes

an information processor analogous to a line in an equation or a digital programming

language. Let’s take a look at several common components.

Resistors reduce the available voltage by converting some of the available power into

heat. They follow Ohm’s law, which states that the current through the device increases

linearly with the voltage across it as determined by the device’s resistance [

Horowitz and Winfield 2015, 4]. Due to their extraordinarily linear behavior, they can predictably convert certain

states to others, and are particularly useful for creating relationships between multiple

time-varying voltage and current sources. A particularly interesting case is potentiometers

which are resistors whose resistance can be internally changed by rotating a physical

mechanism. As we will see below, potentiometers enable user input in the form of

rotating knobs.

Capacitors follow a different type of model which has a time dependence. In capacitors,

the rate of charge (voltage increase) increases linearly with the current through

the capacitor. The ratio is determined by the device's capacitance [

Horowitz and Winfield 2015, 19]. Thus, capacitors can act as timers, producing repeatable change over time as

they charge or dissipate.

Diodes have substantially different behavior than resistors and capacitors because

the current through the device is affected by the direction of the voltage across

it. A diode can be thought of as a one-way valve for current with a minimum voltage

required to “push” the valve open [

Horowitz and Winfield 2015, 31]. In reality, the equation governing the relation between voltage and current

in a diode is very complex. We will use a piecewise linear model that combines the

Constant-Voltage-Drop Model with the Small-Signal model for the discussions in Level

2 [

Sedra and Smith 2015, 190–200].

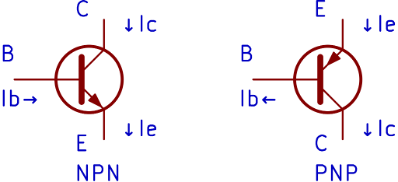

The last component we consider in this article is the transistor, which can be thought

of as an electrical switch, similar to the spigot of a garden hose. It is a three-terminal

device, where one terminal (called the base), allows turning “on” and “off” the flow

of current between the two other terminals (collector and emitter). The Odyssey uses

NPN and PNP Bipolar Junction Transistors (BJT). BJT’s are current controlled devices,

meaning the current through their “base” terminal determines how much current can

flow through their collector and emitter terminals. In Figure 3, we show the symbols

for the NPN and PNP transistor as well as the directions of current through the “positive”

terminals [

Horowitz and Winfield 2015, 71, 76].

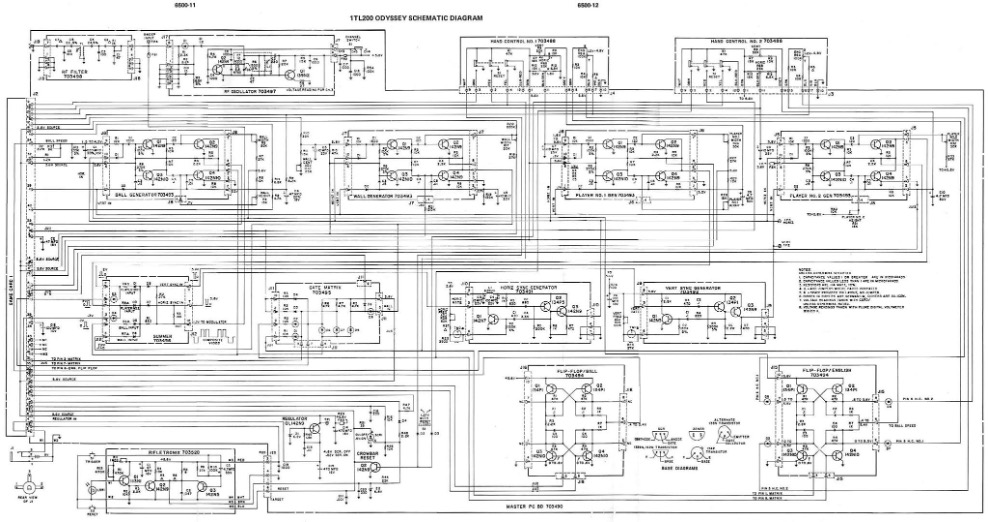

The motherboard hosts ten daughter cards. There are four spot generators (ball, wall,

player 1, player 2), one summer, one “gate matrix”, one horizontal sync generator,

one vertical sync generator, and two flip-flops (Figure 4). Each of these daughter

cards is constructed using a combination of the basic electrical components detailed

above. For example, the sync generators use capacitors to produce regular timed signals

to sync with televisions, the flip-flop uses transistors to switch between two possible

states (directions the in-game ball can travel), the spot generators use transistors

to draw the vertical and horizontal boundaries of player avatars, a ball, and/or a

wall, and the summer uses a series of diodes to combine these various shapes into

a single video signal. The motherboard has one forty-four pin edge connector which

accepts the “game card.” All game cards consist solely of physical connections between

the forty-four pins. The simplest example is a connection from pins two to four which

provides power from the batteries or wall jack to the internal circuitry of the Odyssey.

This function harnesses the analog nature of the console to both power up the machine

and start the game program simultaneously. The motherboard has two twelve-pin Molex

connectors for two controllers. The notable parts inside each controller are three

three-terminal potentiometers and one three-pole,

[3]

double-throw pushbutton switch.

The game card for

Volleyball engages the following functions (Table 1):

| Pin Connections |

Function enabled |

| 2-4 |

Connect supply voltage to 5.6V regulator input (power all circuitry) |

| 6-8-10-14-16-20-22 |

Supply 5.6V to Player 1, Wall, Ball, Wall Shorten Resistor, Wall Widen Resistor. Power

gate matrix output resistors. |

| 13-27 |

Connect ball-wall contact signal to crowbar input (motherboard latch) (setting the

conditions under which the ball disappears). |

| 23-25 |

Connect crowbar active signal to ball disable (causing the ball to disappear when

the above condition is met). |

| 30-34 |

Flip-flop bidirectional resistor output to ball horizontal direction |

| 31-39 |

Player 2 on screen to gate matrix player 2 input |

| 35-37 |

Player 1 on screen to gate matrix player 1 input |

| 42-44 |

Put resistors in parallel to increase ball vertical response speed |

Table 1.

Table of

Volleyball game card’s (#7) connections and functions.

At the hardware level, this is how Volleyball works: The game card “switches on” four spot generators, each of which produces

an on-screen element: two square “players” (simulated volleyball players), one vertical

“net” in the center of the screen, one small “ball,” and a resistor that changes the

vertical timing of the wall-spot generator so that the normally infinite height “wall”

spot is shortened so it resembles a “net”. The ball’s horizontal and vertical positions

are controlled by the charge in two respective capacitors. The charge of the vertical

position capacitor is set by the “English” potentiometer (which appears to players

as the “English” knobs on their controllers) of the most recent player to make contact

with the ball. The charge of the horizontal position capacitor decreases or increases

based on the flip-flop’s state, propelling the ball signal horizontally across the

screen. At the same time, the gate matrix continuously monitors the ball, wall, and

player signals from their respective spot generators. If any two are “on” at the same

time during the electron beam’s scanning of the TV screen (represented internally

by the Odyssey’s oscillators that produce the NTSC timing signals), then the two objects

have made contact on the screen. When the gate matrix detects such contact between

a player and the ball, it sets or resets the flip-flop in order to change the direction

of the ball’s horizontal travel and transfer control of vertical position to the correct

English potentiometer (player controller).

This process, by which a collision between the ball and an on-screen player is detected

and causes the ball to “bounce” in the opposite direction, is a perfect illustration

of the conjoining of the digital and analog in the Odyssey’s logic. The electrical

charge stored and dissipated in the horizontal position capacitor is a purely analog

phenomenon, like water splashed into or draining out of a tidepool. This propels the

ball along the screen. But at the same time, the position of the flip-flop circuit

is binary: it is in either one state or the other (depending on the particular state

of its transistors), and that state determines whence the ball flies. Thus, digital

states are manifested in continuous physical properties within the console.

The summer daughter card combines the signals of the four different onscreen “spots,”

passes this “composite” signal to the RF modulator daughter card and subsequent RF

filter and the output is sent to a raster scan device (consumer television). Thus,

the console’s video output is not merely the final step after the position of each

graphical frame has been rendered digitally by the system, as it would be with most

graphical outputs today. Here, not only does the Odyssey draw each frame line on

the fly, like the later Atari VCS,

[4]

but in addition, the gate matrix monitors the spot generators to determine if any

are on simultaneously at a given position of the scanning beam. As we noted above,

this information is used to detect the coincidence of particular elements — such as

when the ball hits a player spot.

The Odyssey contains no circuitry to arrest the movement of the ball before it exits

one side of the screen or the other. This presents a potential problem for a game

meant to simulate the real-world sport of volleyball, in which making contact with

the net causes the ball to drop to the ground (physical event) and exit play (logical

event). However,

Volleyball simulates these events through the implementation of a “crowbar” circuit located

on the motherboard, routing the ball’s signal through its output terminal. The crowbar,

physically constructed from a thyristor, is best described as a latch [

Horowitz and Winfield 2015, 208]. During normal operation the crowbar is off. When a signal pulse is received

on the crowbar’s input port it activates and connects its output pin to ground. The

crowbar then uses the current flowing through it (from the output terminal to the

ground) to keep itself active (and the output almost shorted to ground) indefinitely.

To bring the crowbar back to the inactive state, the current flowing from output terminal

to ground must be interrupted. The crowbar reset circuitry (hardwired to the Reset

button on the Odyssey’s controllers) accomplishes this by shorting the current away

from the crowbar’s output to ground along an alternate path. Without current flowing

through it, the crowbar becomes inactive due to lack of electrical energy. In

Volleyball, Game Card #7 connects the input and output of the crowbar circuit such that coincidence

between the ball and wall (“net”) spots activates the crowbar, which then renders

the ball invisible by shorting the ball’s active signal to ground. Momentarily, pressing

either controller’s Reset button resets the crowbar (rendering the ball visible again).

Additionally, the losing player’s Reset button flips the flip-flop to its opposite

state, thus resuming the program and sending the ball flying back onto the screen.

The moment the ball makes contact with the net, then, it seems to the players to disappear

from the screen, simulating arrested movement (the physical event of a volleyball

hitting a net). At the hardware level, however, the ball’s signal is still present

— it has been pulled low by the crowbar circuit but not all the way to ground (0V).

Thus, its signal possesses enough voltage to trigger the flip-flop but not enough

to enable the ball’s signal to be added to the console’s output (television) signal

via the summer daughter card. To the user, it appears as if the ball has been eliminated,

but in actuality it is still invisibly bouncing back and forth until it misses one

of the player spots and finally exits the screen. As we will discuss in Level 4,

the logical event of halted play must be enacted by players (prompted by the phenomenological

event of the ball becoming invisible) since it isn’t enforced by the console’s logic.

This invisible ball is a pseudo end-state to the program: it is technically still

running on the hardware, but appears to the players to have stopped, awaiting their

input (the next serve). Thus, the “netted” ball is something of a ghost, actively

haunting the system even after the players believe it to have expired.

The Odyssey’s designers felt that this was an adequate physical approximation of a

game-stopping consequence (as we’ll discuss further at the subsequent levels) that

could be coded without undue expense or complexity. It is an example of hardware

economizing combined with creative programming: in Volleyball the crowbar function is used to simulate the ball hitting the net; whereas, in other

games the crowbar is programmed to simulate a torpedo hitting a ship (Submarine), an airplane being shot out of the sky (Dogfight), a cat catching (and presumably eating) a mouse (Cat and Mouse), or a spaceship burning up in the sun (Interplanetary Voyage). These conditions have very different meanings to players in their different contexts,

even if they all arise from the same hardware function, programmed differently. We

will need to look at higher levels of this code to trace out the process by which

hardware states are transformed into symbolic meaning, but already we have seen that

in analog computing, the hardware layer is a direct substrate for programming. Rearranging

or reconnecting components in different configurations produces different electrical

behavior, enabling new sets of interactions, input, and output. While this is clearly

a continuous — that is, analog — process of altering current and voltage over time,

it is not true that the analog and the digital cannot coexist. The crowbar, the gate

matrix, and the flip-flop subcircuits all utilize continuous flows to encode digital

logic in definite states (invisibility, coincidence, and direction, respectively).

Fully discrete hardware (i.e., digital processors) is not required to implement digital

logic because digital logic can directly interface with analog signals. It may come

as a surprise that the two can coexist quite productively in the Odyssey. However,

this is what historically enabled the decades-long practice of analog computing.

It is commonplace that higher levels of code (from machine to assembly to language

to scripting, for example) are always more abstract than lower levels of code [

Abelson and Sussman 1996, 491–610]. As we’ll argue, however, this is not necessarily the case in our example:

hardware capabilities can reach high levels of abstraction (as the crowbar example

shows); however, higher levels are not necessarily more abstract than the hardware

level. A great deal of

Volleyball’s program is coded directly at the hardware level: game card #7 connects the inputs

and outputs of the circuits we have described, producing these effects. This does

not mean, however, that there are no higher levels of code. After all, what we have

described so far is primarily the movement of electrons through circuits. Higher

levels of this codified system, each of which represents a different way to characterize

Volleyball’s code, were used to program the game, and can be uncovered again through reverse

engineering in order to reveal much more about the game’s nature, how it functions,

and what its programming assumed about its players.

Level 2: Mathematical Operations

In order to understand the formal relationship between hardware platform (Level 1,

above) and logic flow (Level 3, below), we must explore the relation of each to mathematical

formulae. This is the secret to the historical success of the electronic analog computer.

These computers were not only used to model physical phenomena to aid in the design

of everything from aircraft to atomic reactors but also to solve equations that would

be far too time consuming to solve manually or via digital computers of the time.

As Granino Korn noted in 1962, “Unlike digital computers, most analog computers employ

distinct computing elements for each mathematical operation required to solve a given

problem (parallel operation). Parallel operation is an essential reason for the very

high computing speeds possible with d-c analog computers” ([

Huskey and Korn 1962, 1–4]), (emphasis in original). Put simply, analog computers could perform, at very

low levels of abstraction, many mathematical equations directly. Digital computers,

by contrast, could only sequentially perform a fixed set of operations, usually limited

to addition and subtraction [

Brown and Vranesic 2009, 249–295]. Thus, in digital computers, hgher order operations had to be built up

from these lower level ones, necessitating higher levels of software abstraction.

In contrast,analog computers could perform calculus directly at the hardware level

[

Korn and Korn 1952, 8].

A complete mathematical formulation of Volleyball would serve as a legitimate low level expression of its code, but it would require

many pages of this journal. Thus we will only undertake a complete description of

the code at a higher level (Level 3). In this section, we will examine the relationship

between hardware and logic to demonstrate, for two of Volleyball’s functions, how code can be expressed as mathematics that blend continuous time,

continuous values, and discrete meaning.

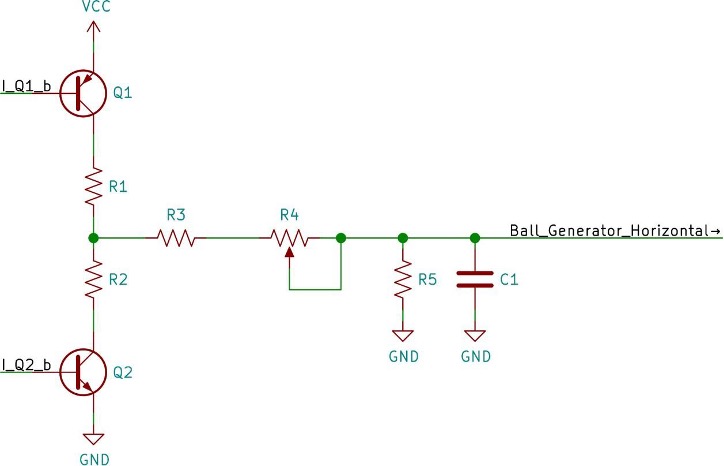

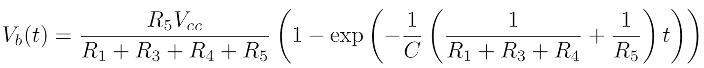

The first example we consider is the regulation of the ball’s horizontal position

by an “integration” circuit in Volleyball (Figure 5). On the left are two transistors that are part of the flip-flop that tracks

the direction of the ball. Their output is the “direction” that charges or discharges

the horizontal position capacitor.

In Figure 5, the voltage between node Ball_Generator_Horizontal (abbreviated Vb) and

ground defines the horizontal position of the ball. Lower voltage means the ball is

further to the right of the screen. Because this differential equation describes a

continuously variable function, there are an infinite number of possible ball positions

described by this equation and instantiated during the running of the Volleyball program. This is strongly in contrast with digital systems that can only support

quantized positions on the screen

The flip-flop has two states, “left motion” and “right motion.” In the configuration

shown in Figure 6, the transistors are complementary, meaning if one is off, the other

is on. In the “right motion” state, the base of Q1 has a high voltage comparable to

its collector, meaning that a current flows through its base pin that is too small

to turn it on. Meanwhile, Q2 has voltage higher than its emitter applied to its base,

great enough that the current through it’s base pin turns it on. Using Kirchoff’s

Voltage Law (KVL) and Kirchoff’s Current Law (KCL)

[5]

, we can write a differential equation for the voltage at Vb for the case of “right

motion.”

Assuming the initial position is beyond the left side of the screen (Vb is a high

voltage like Vcc) then the equation above has the solution [

Tenenbaum and Pollard 1985].

In the case of “left motion” starting from beyond the right side of the screen (Vb

is a low voltage like 0) then the solution looks different, but is qualitatively the

same as shown in Figure 6.

In general, the solution to a differential equation cannot be expressed as an easily

evaluated equation (closed form), as was done for Vb above. When available, such solutions

instantly provide a qualitative description of a systems behavior in all conditions

and are thus very useful for designing a circuit’s behavior. In this example, such

a solution was only available because the transistors were assumed to be in a particular

operating mode which rendered the considered circuitry linear. While more complicated,

nonlinear differential equations can be characterized using simulation or advanced

techniques from dynamical systems theory [

Khalil2002]. using such techniques to qualitatively describe a system as large as the Odyssey

would be an incredibly difficult and labor intensive. Thankfully, individual sub-circuits

can be described qualitatively and “sending” sub-circuit terminals can be connected

to “receiving” sub-circuit terminals without greatly affecting the “senders” behavior.

This property makes it possible for the analog programmer to design behaviors without

considering the entire circuit at once. In the extreme case, it makes the abstractions

later described in Level 3 possible. This illustrates the complexity and nonlinearity

of analog systems.

When used as substrates for computing, these dynamic systems can be harnessed to form

analogs of other complex, nonlinear systems; this was the principle insight that lead

to the field of analog computing. Digital systems, by contrast, are necessarily simplified

models of complex systems, built up through code from simpler to more complex forms.

Put another way, digital computing at this level — which we might call assembly code

— must combine low-level hardware states (binary) into more complex mathematical functions.

To cause a ball to accelerate across the screen, as in this example, the code must

combine many simple arithmetical functions into a differential equation, then apply

that equation to a pre-defined grid of positions to move the ball across the screen

from pixel to pixel. The analog computer, as we have seen, begins with a differential equation that simply describes the physical behavior of electrons

within the circuit. Then, while the digital system must somehow simplify the equation

it has built up, approximating positions within limited matrices, the analog computer

simply feeds its signal into an analog output. The granularity may get reduced by

the output device (the phosphor pattern on a CRT television, for instance), but such

resolution reduction is not part of the machine’s code.

The analog computer converts physical states into symbolic or logical ones through

equations that describe that physical behavior, while the digital computer begins

with simple data, then must build up ever more complex instruction sets to construct

a set of equations to transform that data into results that can be output. In the

analog computer, dynamic states are translated into the symbolic, while in the digital

computer, the symbolic is constructed piecemeal, always under conditions of simplification

and approximation.

At the next level we will examine some of the implications of this difference for

the programmer. First, however, we’ll look at one more example of the Odyssey’s physical

states translated into a symbolic (mathematical) model: the gate matrix’s detection

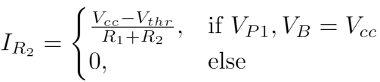

of player and ball contact. The sub-circuit considered is shown in Figure 7.

We can view the circuit as mapping the two inputs (VP1, VBall) to one output (Flip_Flop).

The line VP1 has a high voltage, close to Vcc, when the Player 1 spot is being drawn

on the screen. The same applies to the VBall input. Meanwhile, the output is connected

to the flip-flop that controls the directional motion of the ball. Current through

R2 triggers the flip-flop and changes the direction of horizontal travel of the ball.

Using the circuit laws and models mentioned thus far, the equation for IR2 as a function

of VP1 and VBall can be expressed in piecewise linear form.

In order to simplify this equation, we have to consider the four possible different

cases encompassing all the possible combinations of the voltages on VP1 and VBall.

| VP1 |

VBall |

ID1 |

ID2 |

V1 |

| 0 |

0 |

~0.5*(Vcc - Vthr)/R1 |

~0.5*(Vcc - Vthr)/R1 |

~Vthr |

| Vcc |

0 |

0 |

~(Vcc - Vthr)/R1 |

~Vthr |

| 0 |

Vcc |

~(Vcc - Vthr)/R1 |

0 |

~Vthr |

| Vcc |

Vcc |

0 |

0 |

Vcc - IR2R1 |

Table 2.

Table of solutions for ID1, ID2, and V1 given all possible combinations of VP1 and

VBall.

Thus, across the four possible combinations of VP1 and VBall , V1 there are two possible

output values. With this observation, we can write down a simpler expression for IR2.

In essence, the diodes perform an AND operation between VP1 or VBall and send the

detection of coincidence to the flip-flop.

These equations describe a system of interactions that incorporate both continuous

(analog) functions and discrete (digital) ones. A continuously variable function

(ball position in time) acts on a threshold equation to determine two binary states:

the coincidence between a player spot and the ball spot, and the state of the flip-flop,

which determines which of the two directions the ball travels in.

Unlike at the other levels, here we can see that the mathematical operations clearly

specify the behavior of Volleyball’s physical instantiation in hardware. Similar to assembly code for digital computers,

these equations determine the specific states of physical components — that is, they

describe the behavior of physical systems. However, unlike digital computers, there

is almost a one-to-one mapping between physical states and something perceivable by

the player. These equations mix continuous with discrete, analog and digital. They

describe discrete states of the machine, but as piecewise continuous functions. Thus,

at this critical level of transformation between hardware substrate to abstract logic,

there is no definitive move from the analog to the digital; both are operative simultaneously.

What we observed at the hardware level, then, holds even at the level of translation

into the symbolic.

Thus this level is unique in its affordances for the programmer. For example, if the

game designer (programmer) wishes the ball to travel at a particular speed, then the

equations discussed, and specifically the solution to the differential equation, can

guide the choice of resistors and capacitors that accomplish that goal. Mathematical

notation thus provides us with a glimpse of the transitive nature of Volleyball’s code: it operates upon the material substratum of the console, while remaining

symbolically manipulable by humans at other scales. This is the reason that code can

jump from scale to scale, linking levels together in communicative feedback loops.

Mathematical equations capture an essential aspect of a code’s meaning: the formal

rules by which values are transformed as they pass from one level of abstraction to

another. These are passage points where code can intervene in scalar transformations.

We typically think of mathematics in code as primarily attempting to capture something

about the analog world (encoding the continuous into the discrete) or performing calculations

on other stored numbers. In this case, however, our glimpse at Volleyball’s underlying equations reveal an intricate entanglement of analog and digital functions

that together describe the simplest of on-screen transformations in the program: bouncing

the ball back and forth across the screen. Here there can be no delineated point at

which the analog (phosphors on the screen, current in circuits) has been transformed

into the digital, a threshold beyond which all coded manipulations are in a simulated,

digital world. Rather, analog and digital functions rely upon each other and are interwoven.

The mathematical components of code exert control over the system, but the system

cannot be thought of as a mere simulation of the real. We could not claim that the

ball in Volleyball is definitively digital or definitively analog. Rather, it appears to bounce between

the two.

In this sense the ball in

Volleyball is a unique object in early gaming and early programming, and serves as an icon or

mark of transitivity: it moves of its own accord (according to the equations we’ve

related here); it can be made to bounce, to halt, to disappear, to soar, or slam downward

like a missile.

[6] The ball is a boundary object that can bounce between levels of abstraction, as

both an object operated upon by code and as code operating on its various environments.

These sorts of liminal coded objects are rarely considered as such, but perhaps that

is because the equivalent level at which they can be resolved, assembly, itself receives

little attention. Still, we could look to other boundary objects like wavetable synthesis,

scanners, and quartz oscillators as ubiquitous digital equivalents.

The liminal quality of Volleyball’s ball provides an interesting response to Kittler. Because the ball is both analog

and digital, material and codeable, we can accept Kittler’s argument that continuous

or analog structures are more characteristic of the physical world as a whole while

rejecting his assumption that they are “unprogrammable.” That is, we can accept his

argument that digital systems capture or represent only a small slice of the world

and obscure even that through symbolic abstraction but also reject his dichotomy between

continuous and programmable. Volleyball’s ball demonstrates that continuous structures are very much programmable, and that

code and continuous material substrate can sustain reciprocal, non-reductive relations.

Let’s follow this analog-digital hybrid volleyball on its path as it weaves together

multiple scales, multiple procedures, and multiple bodies.

Level 3: Abstract Logic

When programmers write code and humanities scholars read it, the code encountered

is usually expressed in a high-level programming language. These languages are powerful

because they retain the precision and machine readability of lower levels of code

and at least some of the features of natural language. That is, they use words and

syntax borrowed from natural languages (usually English) wherever possible to aid

in the composition and human readability of the coded program. Code written in a

programming language is semantically unique in that it is addressed to two audiences:

machines and humans.

Programming languages are not available for analog coding. This is because the machine

is an analog of a physical system, not a linguistic one. While any analog program

can be approximately described in natural language (as we have attempted thus far),

there is no necessary connection between sequences of machine instructions and linguistic

sequences that would render language a particularly suitable form for coding analog

machines. Historically, analog computer programmers tended to use a semi-standardized

block diagram notation system to record, check, and disseminate their programs. Similar

to digital programming languages, block diagramming standardized code so that it could

be “set up” (analogous to compiling) on different architectures and understood by

different human programmers. Additionally, the diagrams served as a record of the

code fed to the machine, just as today source code is sharable, archivable, and readable

outside of its particular expression when run on its intended platform.

Block diagramming essentially visualizes the logical flow of a program. Each block

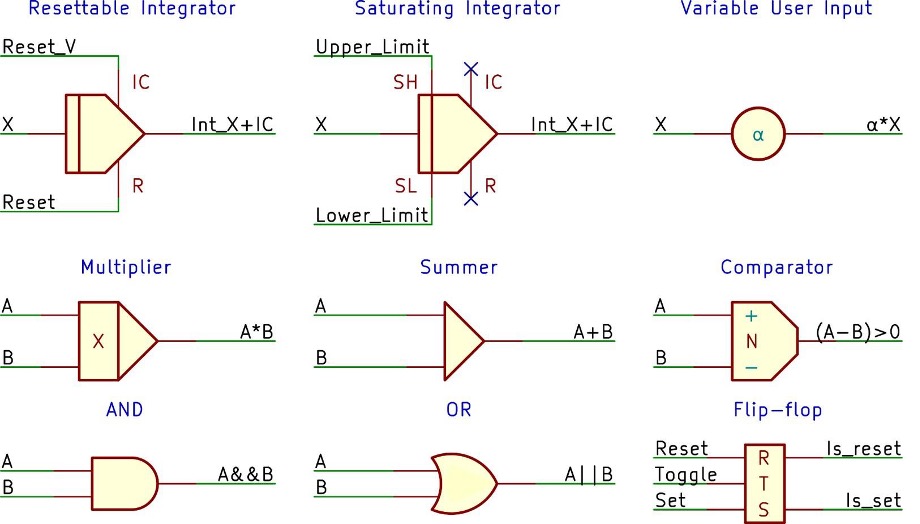

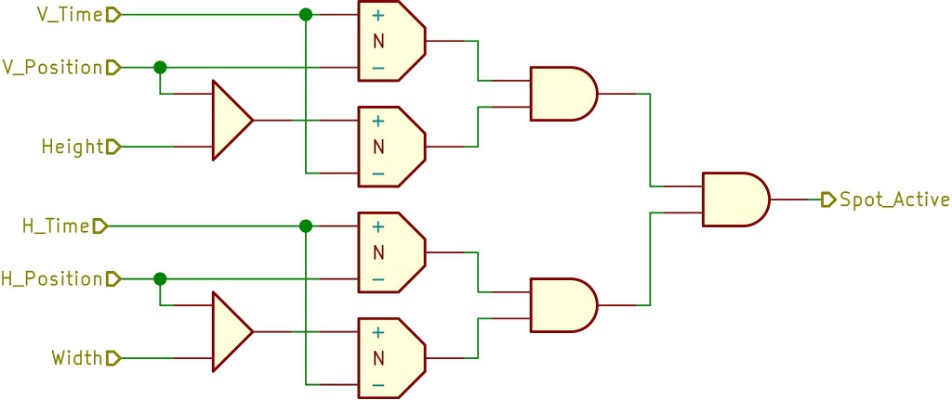

simultaneously represents a logical operation and a hardware component. Figure 8

includes nine basic programming blocks closely adapted from the Handbook of Analog

Computation [

Gilliland 1967]. These are the building blocks of

Volleyball’s code.

These program blocks make intuitive sense to the programmer, and also convey precise

instructions to the machine. To recall our previous example, IF the ball makes contact

with the net, THEN it will disappear. Using program blocks, this could be represented

using an AND block to detect coincidence between the ball and the wall and flip-flops

which latch upon receipt of the AND gate’s output in order to make the ball disappear

for the remainder of the program. Every logical operation that comprises a program

can be diagrammed in this fashion. Volleyball is simple enough to have been programmed entirely in its coders’ heads and therefore

Ralph Baer and his collaborators may never have developed a formal block diagram when

designing its logic. Nevertheless, it is quite possible to reverse engineer the program

and formally express it as code, as we have done in Figure 9.

The spot generators indicated in Figure 9 have the following logical structure (Figure

10):

Notating Volleyball in this way reveals a different aspect of the same code we have explored as hardware

and as a series of mathematical equations. Here we notate not the electrical components,

nor a mathematical representation of voltage transformations, but rather the more

abstract level of logical flow. When viewing the diagram as a whole, Volleyball’s larger-scale relational structure is revealed. We may notice, for example, the

centrality of the ball: it is acted upon directly by the players via their controllers

but also subject to a number of conditional branches that govern its state. As players

of the game, we might expect that our avatars, the player spots, are the most central

objects in the program. However, this logical flow diagram alerts us to the fact

that they primarily serve as input to other processes — that is, as triggers. Very

little affects them, while they affect the logical flow in a number of ways.

From a gameplay standpoint, this produces an interactive system that does not render

its playable characters vulnerable to in-game threats: these avatars have free reign

in the world of Volleyball. They primarily act to constrain their principal medium of exchange: the ball.

On the face of it this isn’t surprising: sports games are usually more about doing

things to a ball than avoiding or mitigating pitfalls directed at your avatar. However,

even in this genre of game, avatars in most sports games are highly constrained by

coded conditional branches. For example, we are not aware of a later volleyball video

game that allows its characters to cross over to the other side of the net during

play. The same sort of conditional branch that causes the ball in Volleyball to become invisible when it makes contact with the net typically halts player movement.

No such conditional branch is present in the above program, and sure enough, players

can move their avatars over to their opponents’ side of the court. They can even

leave the court entirely! Thus the logical structure of Volleyball enacts a particular form of player agency.

Granino and Theresa Korn, in their classic 1952 text on analog programming, take pains

to describe the creativity involved in designing any particular analog computer program:

There are usually many possible setups (programs) for a given problem. It will always

be somewhat of an art to find the setup which will result in the greatest possible

accuracy or in the most economical use of the computing elements. Experience as well

as ingenuity will give the operator a feeling for the new mathematical medium, and

one may say that an elegant setup will be aesthetically satisfying as well as practically

useful [Korn and Korn 1952, 22].

Today’s programmers will recognize and relate to the concept of elegant coding: while

there is no single “right” way to achieve particular results from code, there are

various more or less elegant ways to do so through concision, recursion, and creativity.

As Mark Marino notes, “people who do not program often assume that code is like arithmetic,

with symbols and processes that are expressed in the only way possible. However, programming

actually creates artifacts of processes that reflect the selections made by the programmer

from the paradigm of possible options” [

Pressman and Marino 2015, 29].

In the case of Volleyball, these functions could have been implemented in a number of different ways. What

is perhaps most striking is the economy of this program: it makes use of the absolute

minimum number of conditional branches and drawn elements necessary to simulate a

game of volleyball. It is working within the hardware limitations of its platform,

but as one of the core games written during prototype development, it also influenced

those hardware specifications. For example, an extra resistor and its attendant parallel

wiring and connection to the game card edge connector had to be added to the motherboard

in order to implement the program block we have designated as “Wall Vertical Height

Selection” above. This is the function that limits the height of the Wall spot in

order to refashion it into a short volleyball net. Out of twenty-eight commercially

released Odyssey games, only Volleyball actually calls this function (via a trace on game card #7).

Another feature linking hardware with logic flow that is revealed by block program

notation is the vertical and horizontal timing sources built from self-resetting integrators.

Together, the analog output of these circuits represent the X-Y position of the television’s

electron beam and thus sets the timing for the entire program. It is remarkable that

this sense of time is accomplished purely using program blocks. In digital computers

this is not possible, since time is discrete, and must be incremented by some external

source such as a crystal oscillator [

Heiserman 1978, 14], [

Patterson and Hennessy 2014, 33]. Here, by contrast, the bidirectional coupling of analog and digital elements

in the program, their mutual permeability, enable digital events to occur in continuous

time.

Like most code,

Volleyball mediates between human-readable accounts of the world and machine-readable models

of non-ambiguous instruction. Annette Vee describes this dual function of programming

compositionally as “the constellation of abilities to break a complex process down

into small procedures and then express — or ‘write’ — those procedures using the technology

of code that may be ‘read’ by a nonhuman entity such as a computer. To write code,

a person must be able to express a process in hyper-explicit terms and procedures

that can be evaluated by recourse to explicit logic rules” [

vee2017, 22]. While Vee compares the machine-logic structure of code with its linguistic

properties, our block programming notation is primarily visual and networked rather

than linguistically expressed. Does this help (or compel) us to conceive of the human-readable

layer of code, or indeed its composition, differently?

Visualizing logical flow privileges particular machine actions and opens up spaces

for inputs and outputs at other levels of abstraction. This is the level at which

we can study code for its syntactic qualities and topological structures (especially

loops). We can look for linearity or circularity, openings for inputs and opportunities

for outputs. It is the level at which potential is closed and captured for particular

logical structures.

Another characteristic of

Volleyball that is far less apparent at the hardware or mathematical levels, but which is readily

revealed by its programming block diagram, is the precariousness of its main loop

structure. Video game programs typically require a program loop that continually

reads input states, calculates trajectories, tracks progress, remembers inventory

and score, and draws the onscreen graphics and sends them to a frame buffer [

LaMonthe 1995, 34–43]. If the program loop is interrupted (by someone yanking the power plug out

of the wall, for instance), the current state is lost and the program must start over

from the beginning (though it may re-load saved data). In

Volleyball’s program logic, certain timed input pulses continue indefinitely and the positions

of any spots are continuously drawn, but all of the interactive logic of the game

relies on a loop created by successive flip-flop activations. If a flip-flop is not

activated within a particular period of time, the loop terminates. Player spots are

still drawn, but no interaction is possible. To the players, the game has become

inert. No set of computational instructions necessarily repeats as a result of

Volleyball’s logical structure.

If Wilfried Hou Je Bek is right that we should “regard the loop as a species of tool

for thinking about and dealing with problems of a certain nature” ([

Hou Je Beck 2008, 180]) then

Volleyball’s contingent loop is a telling detail in the conceptual flow of this game. In practice,

the “volley” in the game’s title refers to a sustained, repetitive sequence of a ball

bouncing off the left and right players. But as we can readily see, this sequence

can’t repeat without direct player input via the controllers. Our program block diagram

reveals that there is no loop connecting an internal signal to the “Player 1 Position”

composite block in Figure 11. In this sense,

Volleyball has a limited runtime without active input. The code will have run its course once

the ball exits the screen and only uninteresting periodic behavior will be produced

by the system, driven by the oscillations of the vertical and horizontal time sources.

In essence, if no player intervenes, the program grinds to a halt. The ball will

not be returned from off the screen, and will not be automatically served. No demonstration

sequence or player prompt will load. In Alexander Galloway’s useful conceptual schema,

Volleyball does not include in its program loop what Alexander Galloway calls “ambiance acts,”

or diegetic actions performed by the machine without operator input [

Galloway 2006, 10]. The program will have halted until a player presses their Reset button, which

begins the program again.

Volleyball’s loop structure represents a way of thinking about code-mediated interaction as

a player loop. Rather than external players merely triggering timed inputs that modify

the specific expressive details of the program loop, which is otherwise internally

consistent and self-sufficient, here the loop requires the analog world in two-way

participation. This program loops through physical space rather than treating physical

space a mere input to be encoded.

This radical form of programming helped to usher in an entirely new form of human-computer

interaction: the video game.

Level 4: Game

In order for Volleyball to be fully playable, its program logic must be supplemented with another, higher

level of code that allows it to cohere as a particular type of program: a game. At

this level, the user is included as part of the program, and its larger operational

context comes into view. For a program that is meant to be a game, this is the level

at which it can be played.

Typically, when analyzing digital code, the user can be bracketed out of the discussion,

assumed as a given, but at a higher level of abstraction than code itself. As Montfort

et al. note, critical code studies is methodologically located in between the scales

of platform studies (underlying hardware) and software studies (processes, users,

and cultural context), even if these scales and approaches tend to blend together

in scholarly work (Montfort et al. 2012, 7). But once again, Volleyballand the Odyssey confound even the fuzzy distinctions between these levels. Just as

the code makes no sense without reference to the hardware level (the medium that embodies

its logic and makes it “live”), so too must we confront the fact that the game doesn’t

even become a game, doesn’t become executable, without reference to a higher level

of abstraction that includes human players in a closed circuit with the signal paths

we’ve been describing, as well as natural language rules that are an essential part

of the program’s instruction set. As we shall see, when analyzing Volleyball, it is difficult to make even an analytical distinction between these scalar levels.

Perhaps the most surprising twist in this game for today’s first-time players is that

the Odyssey doesn’t simulate gravity: the ball is not coded to fall downwards! When

hit by a player, as we have seen, the ball changes direction via a digital flip-flop

and increases its speed through the charging of an analog capacitor, driving it to

the right or left depending on the initial condition before the coincidence of ball

and player. But the ball’s vertical position as it travels is determined by the setting

of a special (third) knob on the player’s controller: the “English” knob. Turning

this knob directs the ball upward or downward. The ball’s upward arc, apogee, and

downward arc, together simulating the effects of gravity, are encoded not by game

card #7, nor any digital or analog logic hardwired into the motherboard, nor by a

differential equation, but rather by two very human-readable sentences on the game’s

instruction sheet: “Each player must use his ENGLISH Control to arch the ball over

the NET and then down into his OPPONENT’S playing court. The ball must be directed

down towards the floor of the court and is not permitted to go off the screen at the

TOP or SIDE” [

Magnavox 1972, 1].

The result, as surely as the insertion of a parabolic equation in a line of program

code, is that the ball tends to arc over the net and then drop down to the bottom

of the screen. Such is the power of code.

The “Set Up” section of the same document instructs the player, as the second step,

to “place the VOLLEYBALL Overlay on the screen” (Volleyball 1972, 1). The overlay

in question is a thin, offset-printed sheet of plastic cut to fit the distinct rounded

CRT screens of 1960s and 1970s television sets (Figure 11). All but one of the Odyssey’s

twenty-eight released games uses a similar overlay. These overlays make use of a

mixture of three optical effects: opacity (via a special opaque layer applied to the

back that blocks all onscreen elements when they pass through the coated area), translucency

(via graphics printed on the front of a frosted substrate), and transparency (non-printed

areas on a clear substrate). The entire Volleyball overlay is translucent: on-screen graphics project through the overlay but pick up

the color printed thereon. The yellow backdrop of the Volleyball overlay tints both the players and ball distinctly yellow, presumably evoking a beach

setting.

The overlay’s design includes two squares. As the instructions explain, the players

must position their avatars inside these “boxes” for every serve. Here, then, written

rules reference and require the on-screen game logic and resulting luminescent shapes,

as well as the physical overlay, which composites two sets of images (those produced

via the cathode ray tube and those statically printed on the plastic sheet). Both

the algorithm (set of instructions) and the elements necessary to execute it span

across multiple media and modalities: graphical overlay (with optical properties of

reflection and refraction), natural language instructions, coded machine behavior

via game card #7 and the various digital and analog circuits it modifies, and human-generated

input governed by the affordances of the Odyssey controller — including the semantic

affordance of the prominent label for its one and only button: “Reset.”

Pressing a button labeled “Reset” in order to serve a ball induces some cognitive

dissonance. Ralph Baer’s final prototype for what was to become the Odyssey, his

“Brown Box,” labeled its corresponding button “Serve.” The Magnavox team changed

the button’s label (though not its function) to “Reset.” The semantic difference

is stark: to “serve” is to provide service to another person, to provide them with

the ball, and to set a projectile in motion. It is a narrative act, both initiatory

and consequential. To “reset,” on the other hand, is to return to the beginning,

to start over. This is a user action that effects a change of machine state: in this

case, enacts a loop that keeps the program running. Here, then, is the missing link

in the machine code’s loop. It is offloaded to human action, but certainly not decoded

or uncoded: the “Reset” button ensures that the human player is not only physically,

but logically and semantically enrolled into the game’s series of machine actions

as a fundamental element of its program logic. In Alexander Galloway’s typology,

which contrasts machine actions vs. player actions on one axis and diagetic vs. non-diagetic

actions on the other ([

Galloway 2006]), this is an example of a non-diagetic machine action (loop end state) masquerading

as a diagetic machine action (ball out of court), prompting a diagetic player action

(serving the ball) that nonetheless reveals its non-diagetic nature (restarting the

program loop) via the tellingly labeled “Reset” button. While this tell-tale sign

is the most blatant slip of the curtain, it is characteristic of much of the game’s

logic of simulation. Even human vocalization and memory are drafted as game functions:

the players must keep a running tally of their scores, calling them out and retaining

the arithmetical chain until a winner can be declared.

The Odyssey in general, and

Volleyball in particular, can be regarded as exceptionally economical in its design when, from

this angle, we trace the ways that its program code jumps media and seamlessly meshes

them together into a necessarily complete circuit of coded behavior. The overlay,

natural language instructions, mathematical functions, logical program flow, and individual

physical states all work as part of a larger assemblage to define the bounded system

that is the game

Volleyball. There is no redundancy between, for example, the instruction set given to the human

players and the instruction set given to the machine. Not only is gravity offloaded

to players as an aspect of gameplay (governed by formal rules) rather than as a machine-enforced

constant,

[7]

but scoring too is given over to players to adjudicate and mentally tally. The instruction

sheet explains that where on the overlay the ball exits determines who receives points

or takes the next serve.

Of course, players aren’t forced to follow these rules if they don’t wish to do so.

This represents a significant difference between this distributed, analog-digital

system and purely digital ones: digital code has a finality about it — a way of enforcing

constraints without relying on formal human-addressed rules to do so. As Cathy O’Neil

argues, digital systems and their black-boxed algorithms “define their own reality

and use it to justify their results,” creating feedback loops that foreclose appeal

and tend to perpetuate injustice [

O'Neil 2017, 7–11]. Lawrence Lessig has made a similar point about the autocratic nature of

code, arguing that it prevents unauthorized behavior from the beginning, which circumvents

a fundamental right of citizens to a legal process to challenge unjust rules. In

programmed systems, “code is law” [

Lessig 2006, 5]. When the rules are baked into the system they cannot be challenged. Compare

this to

Volleyball, which codes no prohibition on where players may or may not move during the course

of the game. The human code dictates that “each player must stay on his own side

of the net,” but the machine code does not enforce this. It is a rule, but one that

can be broken: as we have noted, players can move to their opponents’ sides of the

net, and even outside of the visible area on the television screen if they wish.

This “breaks” the game, of course. Players can probe the edges of the machine logic,

but must adhere to the semantic content of the rules and self-police them or the program

doesn’t work. A reversal of priorities, then: the program requires a higher-level

set of semantic structures in order to function correctly. Human language structures

the logic system, rather than the logic system rigidly determining the sorts of semantic

content that can emerge from play. In one sense, then,

Volleyball is rigidly structured by rules. In another, though, the distribution of those rules

across various media and abstraction levels allows them to be differentially (and

creatively) applied, opening up a new space for experimentation and creative interfacing

with the system. McKenzie Wark has argued that such engagement with games can help

players to navigate and find ways to subvert or break everyday reality, which is increasingly

structured by digital system dynamics and marked by gamification. This technosocial

milieu, which Wark calls “gamespace,” has saturated life itself and transformed it

into an agon that instrumentalizes all action and reifies the values of capital [

Wark 2007, 8]. In gamespace, literal video games have the potential to reveal the ways that

players’ relationship to reality has been coded:

“The game opens a critical gap between what gamespace promises and what it delivers,” acting as the first step toward dismantling its ideology and discovering ways to

subvert its everyday functions [

Wark 2007, 32]. Playing games in this way enables the player to “trifle with the game to understand

the nature of gamespace as world — as the world” [

Wark 2007, 21].

If games are simulations — of particular spaces, times, and relations, or of gamespace

as a whole — and analog programs are also simulations or analogs of particular states,

then we must emphasize here that Volleyball troubles the usual relationship between model and reality. This program is meant

to simulate a volleyball court and ball, and two humans playing its titular sport.

In standard computational simulations (including analog ones), humans tweak variables

and observe how the system behaves. In video games, variables take the form of timed

inputs encoded through physical interfaces: buttons, joysticks, voice commands, gestures,

and so on. But while that is still true for Volleyball, the simulation is less autonomous and less autocratic. That is, this coded system

does not foist the constraints of the simulated reality on the user and challenge

them to perform within those constraints. Here, code is not law, and the simulated

world it conjures is permeable with the reality it simulates. As we have seen, Volleyball calls its players to a somewhat different challenge: rather than understanding and

mastering this new, coded, virtual reality, the player is tasked with completing the

simulation itself, with closing the gap between model and world, analog and referent.

The players must add gravity to this simulated beach volleyball game. The players

must keep the program loop going by constantly resetting it (flipping the flip-flop

and recharging the horizontal position capacitor) via their Reset buttons. The players

must enforce their starting positions vis-a-vis the mediation of an overlay that is

not part of the machine code and thus can only be integrated by the human nervous

system. The players must supply the interpretation of various plays to adjudicate

and assign scores. The players must supply the memory to keep track of these scores

and declare a winner. We may read this as a particularly neoliberal enrollment of

human capability into gamespace (not only do the players have to perform within a

simulation, they have to take on the labor of completing the simulation that enslaves

them), or we may read it as something of an inverse of today’s ubiquitous and seamless

gamespace: instead of restructuring (gamifying) the player’s relations with the social

and material world by instrumentalizing and quantifying their actions and enrolling

them in a milieu of perpetual competition, Volleyball asks players to generate their own bridge from the virtual to the real. In this

conception, instead of gaming exposing the gap between a promised milieu and its actual

mechanics, as Wark argues is the norm today, gaming here represents playing in and

exploring the gap itself, in the notable absence of teleology or promises.

One of us, Zachary Horton, often teaches the Odyssey platform in his undergraduate

courses and has witnessed many students struggle with Volleyball in particular. Players must use three different knobs and one button nearly simultaneously

to keep the program running (Figure 12). While it is not unusual for games or other

software to require difficult, coordinated patterns of movement (this is notoriously

endemic to the street fighting genre of video games, for example), these functions

are usually tied to avatar or user actions rather than the layer of simulation itself.

While controlling multiple continuously variable processes with only two hands is

indeed difficult for most players, the true challenge of this game is, we hypothesize,

due less to poor hand-eye coordination than it is to the conceptual leap, unfamiliar

to today’s gamers, from inhabiting an immersive simulation to completing and maintaining

it. Roughly speaking, the conceptual leap in the mentality of the player is equivalent

to the conceptual shift inaugurated between analog and digital coding. The Odyssey’s

players complete both its electrical and conceptual circuits, tracing a continuous

line from their embodied experimentation to the logical flow of its program to its

humming hardware. No level is fully self-sufficient, and none can pretend to subsume

the others.

It is no small trick to maintain the enmeshed meta-stability of this multi-level,

multiscalar, multi-modal system. As we have seen, intricate programming that spans

modes, scales, and levels of abstraction is required. Volleyball, as a game, and the Odyssey, as a platform, are exemplars of what we might call multi-level

coding. This style of programming addresses multiple scales simultaneously, exchanging

information between them, and thereby weaving a tapestry of digital states, analog

contours, natural language instructions and machine instructions, physical affordances

and symbolic transformations. As we have argued, Volleyball’s code is not reducible to any one of these strands; it only comes into focus as

a human-computer assemblage when all are considered and traced as enmeshed processes.

The Odyssey challenges not only our common assumptions about the strict programmatic

separation between the analog and the digital, but also the role of video games in

computational history. Volleyball makes a compelling case for early video games as far more innovative and consequential

than as merely one subsidiary category of home software focused on self-contained

simulations. Volleyball is porous rather than self-contained, a program that enters and incorporates the

material world rather than a hermetically sealed digital simulation. Players have

to do far more than learn the algorithms of the system and optimize their performance

within it: here they become active authors in the primary program loop, actualizing

and sustaining the code as if they were part of the hardware platform — which indeed

they are. The Odyssey may not attempt to teach its players anything about formal

computer programming, but it does teach them how to integrate with, realize, and tweak

complex human-computer systems that render commensurate radically disparate scales

and modes. Far from being merely primitive versions of later digital simulations,

the generation of games to which Volleyball belongs were charting a radical path devoted to bringing worlds together and teaching

their players how to sustain these new, hybrid human-computer assemblages.

Conclusion

We have traced an unusual program coded for a mostly forgotten platform as a deliberately

provocative edge case for critical code studies, and academic study in general. Not

everyone, we think, would agree that this program constitutes code at all, if we insist

on defining code as discrete symbolic characters that are encoded in a binary system

and compiled for general processors consisting of transistorized logic gates. However,

we would argue that none of these features are necessary for a program to be considered

code. As we have shown, even extremely limited-purpose analog computer programs possess

the same logic operations, abstract layers, and semantic context as digital code.

The fact that Volleyball does not prioritize any particular level of abstraction nor set of linguistic conventions