Notes

[1] Lovelace’s modern reputation can be traced back to

Alan Turing’s 1950 article, “Computing Machinery and

Intelligence.” Soon after, her reputation was solidified by B.V. Bowden

in Faster Than Thought (1953) and later D. L. Moore,

who claimed that Lovelace was “the first computer

programmer.” Subsequently, the Department of Defense first began

developing the Ada programming language in her memory (1977).

[2] The “Sketch,” published on August 24, 1843,

was considered a success by its small audience. Babbage would later write to

Lovelace’s son, Byron Noel, that his mother had written “the

only comprehensive view of the powers of the Analytical Engine which the

mathematicians of the world have yet expressed” (1857). However, the

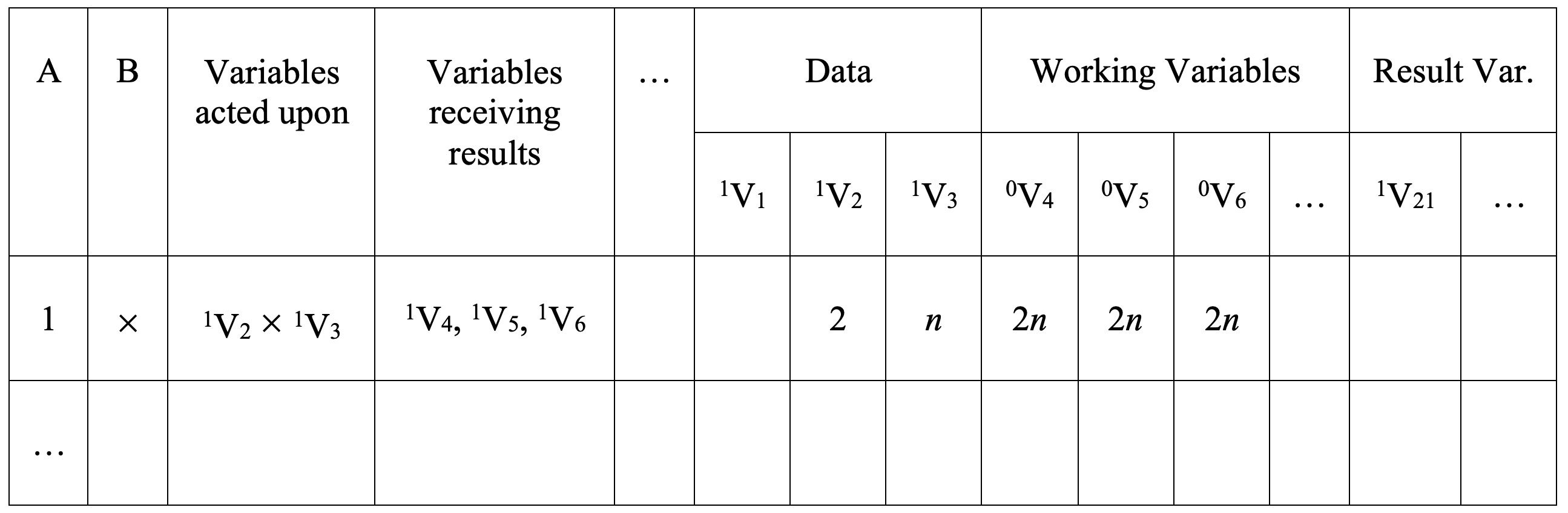

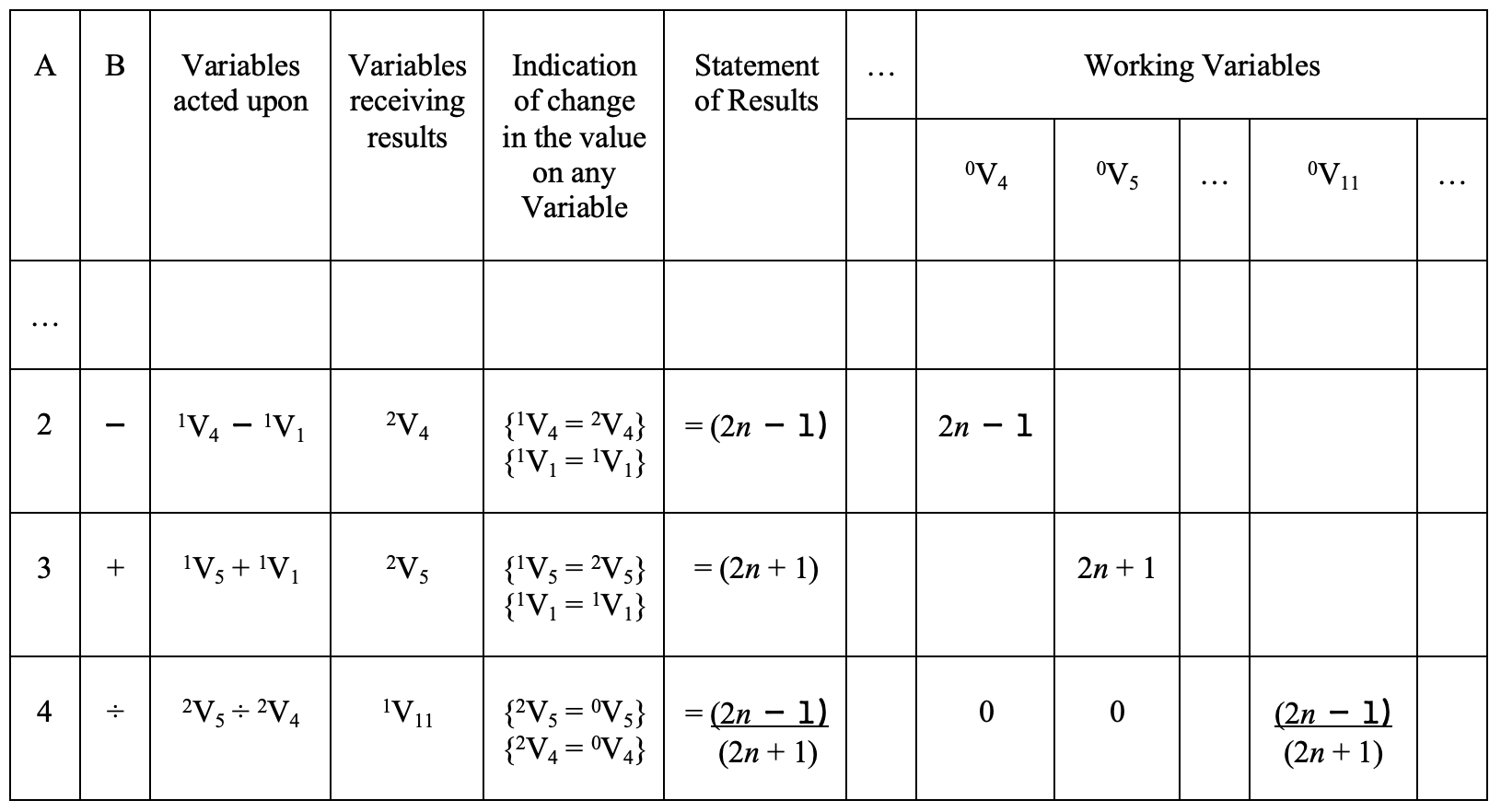

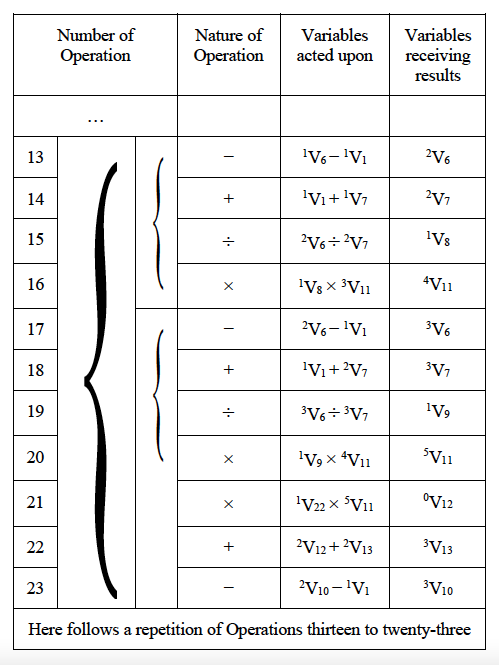

article was not widely read and not republished until 1889. This paper uses the

version online at: www.fourmilab.ch/babbage/sketch.html

[3] The debate around Lovelace has a long

critical history. D. Stein, in Ada: A Life and a

Legacy (1985), wrote off Lovelace as “a figure

whose achievement turns out not to deserve the recognition accorded it”

[Stein 1985]. A. Bromley has refuted Lovelace’s reputation as the

first programmer [Bromley_1990]

[Bromley_1990]. M. Campbell-Kelly echoed Stein when he wrote that

“the extent of Lovelace’s intellectual contribution to the

Sketch has been much exaggerated” (1996), and many other works on

Lovelace have overly focused on her biography and temperament. However, a counter

narrative simultaneously emerged. J. Baum’s The Calculating

Passion of Ada Byron (1986) treats her writing seriously, and B. A.

Toole’s Ada, The Enchantress of Numbers (1992) has

inspired many works, some cited in this paper, to treat Lovelace as an important

innovator in computer history. This article follows Roger Whitson’s claim that

Lovelace’s contribution becomes salient when we make room for “critical

making” in intellectual genealogies [Whitson 2015, p. 166].

[4] The Notes were a collaborative effort:

Babbage and Lovelace “discussed together the various

illustrations that might be introduced.” He remembers in his

autobiography that “I suggested several, but the selection was

entirely her own. So, also, was the algebraic working out of the different

problems, except, indeed, that relating to the numbers of Bernoulli, which I

had offered to do to save Lady Lovelace the trouble”

[Babbage 2019]. But even if Babbage had provided her with the

original equations, it was Lovelace who translated the algebra into a step-by-step

algorithm of her own design — an achievement which, as Thomas J. Misa outlines

extensively, is “reasonably clear” and “clearly indicated” in her letters [Misa 2016, p. 14, 26].

[5] Melissa Terras and Julianne Nyhan here are

quoting Marco Carlo Passarotti of the CIRCSE Research Centre. Terras and Nyhan

also point out that “the names of the women have not been

preserved in the historical record”; maybe because the Index Thomisticus was one of the first digital humanities

projects, DH projects today often unwittingly reproduce a similar labor structure

[Terras and Nyhan 2016, p. 61–63].

[6] The use of loaded

jargon (like “slave”) has recently been reconsidered in science

and technical writing, related to ants and programming languages respectively.

Though useful in a vacuum, such terms imply analogies between human and nonhuman

behaviors. Ron Eglash makes the historical connection between late

nineteenth-century uses of “slave” and

“servant” in engineering (e.g., servomotors and slave

clocks) to Charles Babbage, crediting his 1832 book On the

Economy of Machinery and Manufactures for popularizing the division of

high-level and low-level thinking in labor (“Broken Metaphor:

The Master-Slave Analogy in Technical Literature,” in Technology and Culture Vol. 48 No. 2 (2007), 367). It should also be

noted that Black slaves invented many new technologies but did not own their

inventions. See: Rayvon Fouché, Black Inventors in the Age of

Segregation: Granville T. Woods, Lewis H. Latimer, and Shelby J.

Davidson (JHU Press, 2005).

[7] In response to claims of her emotional stability and mathematical amateurism,

scholars who defend Lovelace’s historical significance refer to the creative

thinking which she provided and which Babbage seemed to lack. “Lovelace’s Leap” usually describes her impulse to ask what if. Even Doron Swade, who has marginalized Lovelace’s role in the

past, argued in an interview for the documentary To Dream

Tomorrow that “What Lovelace saw […] was that

numbers could represent entities other than quantity”

[Fuegi and Francis 2003, p. 24]. She suggests that because the Engine

might act upon non-number variables, it might produce things besides numbers if

those original variables (notes, colors, etc.) shared a relationship expressible

by algebraical operation.

[8] I am referring to women, like Elizabeth Cary, who

translated Italian plays in Early Modern England, and works of science from one

European language to another; famously, Emilie du Chatelet translated Isaac

Newton, Clemence Royer translated Charles Darwin, Anna Helmholtz translated

Tyndall, and Marie-Anne Paulze Lavoisier translated her husband. Mary Somerville’s

entry into the elite scientific societies of London was based on her translation

of Pierre-Simon Laplace’s Traité de mécanique

celeste (or The Mechanism of the

Heavens, 1831), only after which she was able to publish her own work,

starting with the very successful On the Connexion of the

Physical Sciences (1834).

[9]

Babbage remembered that Lovelace sent back the Bernoulli calculations he had done

for her, “having detected a grave mistake which I had made in

the process”

[Babbage 2019, p. 136]. The nature of this mistake is not

known, but this anecdote reaffirms why the machine was invented. She had also once

criticized the published work of her tutor, Augustus de Morgan, and was proven

correct years later.

[10] The Analytical Engine was never built, and unlike the Difference

Engine, it was never drafted with consistent enough technical detail to provide

functional blueprints. It existed only in the minds of Babbage, his principal

draftsman Joseph Clement, and Lovelace. It exists today only as an idea, scattered

across Babbage’s journals, and most definitively in Lovelace’s words. Indeed, the

“Sketch” serves as the blueprints Babbage never

published; Allen Bromley writes that, “aside from the

Bernoulli numbers program prepared for Ada Lovelace’s notes, there is no

evidence that Babbage prepared any user programs for the Analytical Engine

after his 1840 trip to Turin.” (“Allan Bromley

Explores Babbage’s Analytical Engine Plans 28 and 28a,” IEEE Annals of

the History of Computing, 2000, 11). By 1837 Babbage had produced many stereotype

plates. He distributed them but never published them, and they are far from

complete. All this said, like Maxwell’s demon, Schrodinger’s cat, and Sadi

Carnot’s engine, the Engine is a thought exercise that has launched its own

discourse.

[12] These are the two

main arguments against the diagram’s definition as “code,” and

they are both contested positions. For one, the difference between machine and

higher-level code — the difference between an algorithm to solve an equation and

an abstracted, linguistic command — is mostly about proximity to hardware. The

idea that code is only code if it is executable may make some theoretical sense; a

programmer “is produced through the act of programming”

and a “source code only becomes a source after the

fact”

[Chun 2008, p. 24]. But in practice, code is often not

executed and sometimes designed as such (e.g., code poetry).

[13] The following endnotes provide an explanation of the

punch card system, paraphrasing Lovelace’s translation, both her and Menabrea’s

words (with help from other works cited in this paper). While Babbage only

describes two types of punch cards in his journals, by the time the Notes are written, there are at least three. Operation Cards determine the algebraic state (add,

multiply, etc.). Variable Cards inform the machine

which columns (V’s) in the “Store” to fetch values

from and deliver intermediate results to. These are alternately expressed by

Lovelace as either Supplying Cards or Receiving Cards, of which there are usually three per

operation. For instance, if the machine needs to add together variables A + B

to make C, an Operation Card will activate the

“addition” state, two Variable Cards will “supply” A and B by

designating the two columns where they are stored, and a third Variable Card will identify a third column to “receive” the calculated sum C (at which point the

calculation will end, or C can be further used as a new variable in a future

operation). These Variable Cards contain

additional information, such as whether the column should be reset to zero

after the calculation is complete, whether the number should be toggled between

positive and negative, and whether the column should be treated as a quantity

or, in the case of indices of power, types of “operations” (in which case Variable

Cards are called upon to act as Operation

Cards). Rather than pointing to columns, Number

Cards, Menabrea explains, specify an actual number (or algebraic

expression); these cards are used for timesaving: For example, by having a

complex value such as Pi already expressed by

punch card, the Engine is saved from calculating Pi every time it is needed to determine a circumference. This

would allow the Engine to, for instance, calculate the next Bernoulli number

without having to calculate the preceding one.

[14] A

possible fourth type of punch card, called Combinatorial

Cards, are the least explained in published materials but probably

the closest approximate to code. These cards are instructions to the Engine for

manipulating the other processes. If all punch cards used in a calculation

enter a “library” — a sort of holding area, or cache —

Combinatorial Cards can manipulate the prism to

access those already used cards and/or skip others. As Lovelace explains in the

Notes, because punch cards are entered into the

Engine in a particular order, the Combinatorial

Cards can do two things: (1) enter the prism into a “reverse” or “forward” state,

and (2) set an end variable so the machine knows when to return to normal

function. As Plant points out, “The cards were selected by

the machine as it needed them and effectively functioned as a filing system,

allowing the machine to store and draw on its own information”

[Plant 1995, p. 52]. This greatly reduced the number of

cards required; the calculation of the eighth Bernoulli number required under

100.

[15] As Wilfried Hou Je Bek points out,

the term LOOP denotes a vast chain of beings (iterators, GO TO statements with

passing arguments, count-controlled loops, condition-controlled loops,

collection-controlled loops, tail-end recursion, enumerators, continuations,

generators, Lambda forms, et al.) [Hou Je Bek 2008, p. 182]. It includes two parts that are no different in function but different in

cause and feel: iteration and incursion. The PERL glossary defines “iteration” as “doing something

repeatedly.” The entry for “recursion”

begins: “The art of defining something in terms of

itself,” and ends: “[Recursion] often works out

okay in computer programs if you’re careful not to recurse forever, which is

like an infinite loop with more spectacular failure modes.”

[16] Babbage is credited with inventing

the general-purpose computer for the same reasons that the Analytical Engine is

different than the Difference Engine and the Silver Lady. Those automatons each

have single states: add or dance. But the Analytical Engine allows for both

variables and different states. While a washing machine allows for settings

(hot and cold) and uses multiple states (rinse and spin), the Engine, due the

programmer’s ability to set values, branch, and loop, allows for an infinite

amount of “free play” between variables and states. It is

that quality which, in addition to her Leap, Lovelace expresses so beautifully

in the Notes — an illustration of the Engine as

“the material expression of any indefinite function of

any degree of generality and complexity” (“Note

A”). As Angluin put it, “There in [the 1843

paper], a century before its time, is the concept of a general-purpose

digital computer, developed to an amazing degree of sophistication”

[Angluin 1976, p. 6–7].

[17] According to Fuegi and Francis,

Howard Aiken referenced Babbage’s designs in 1937 while working on the electric

calculator for IBM, and Konrad Zuse encountered Babbage’s designs the same year

[Fuegi and Francis 2003, p. 18]. Actual software would not be theorized

until Turing or fully realized until the Manchester Baby in 1948.

[18] The labor organization that Chun

describes at Bletchley Park persisted until the invention of automatic computer

programming allowed coders to communicate with these new subprograms instead of

the machine directly. Ironically, this sparked fear that the

“manly” practice of coding was becoming de-skilled. Instead

of suffering through machine language like a “real man,”

shortcuts allowed programmers to write without knowing how the subroutines worked

[Chun 2008, p. 43]. The development of such languages ended

up displacing mostly female computers and ushering in a male-dominated era of

computer science. Chun points out that the very anxieties around feminized

software have, more recently, “paradoxically led to the

romanticization and recuperation of early female operators of the 1946

Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC) as the first programmers,

for they, unlike us, had intimate contact with and knowledge of the

machine”

[Chun 2008, p. 19].

Works Cited

#Chuan Chu 2008 Chu, J.C. (1980). “Computer development at Argonne National Laboratory”, in N. Metropolis, J. Howlett and G. Rota (eds.) A History of Computing in the Twentieth Century. Academic Press, pp. 345-346.

Abramson 2008 Abramson, D. (2008) “Turing's responses to two objections”, Minds & Machines, 18.

Angluin 1976 Angluin, D. (1976) “Lady Lovelace and the analytical engine”, Newsletter

of the Association for Women in Mathematics, 6, pp. 6-8.

Babbage 1864 Babbage, C. (1994). Passages from the life of a philosopher. (M.

Campbell-Kelley, Ed.). Piscataway.

Babbage 1961 Babbage, C. (1961) “Of the Analytical Engine”, in P. Morrison and E. Morrison (eds.) Charles Babbage and His Calculating Engines: Selected

Writings. Dover Publications.

Babbage 2019 Babbage, C. (2019) Passages from the life of a philosopher. Good Press.

Balsamo 2011 Balsamo, A.M. (2011) Designing culture: The technological imagination at work.

Duke University Press.

Bolter and Grusin 2000 Bolter, J.D., and Grusin, R.A.

(2000) Remediation: Understanding new media. MIT

Press.

Bowden 1953 Bowden, B.V. (1953) Faster Than Thought. Pitman Publishing Corporation.

Bromley_1990 Bromley, A. G. (1990). “Difference and analytical engines”, in W. Aspray (eds.) Computing before computers. Iowa State University Press, pp. 59-98.

Brown 2018 Brown, S. (2018) “Delivery service: Gender and the political unconscious of digital

humanities”, in Bodies of Information: Intersectional

Feminism and Digital Humanities, pp. 261-286. Minnesota University

Press.

Burton and Hicks 2020 Burton, E., and Hicks, M.

(2020) “A history of women in British telecommunications:

Introducing a special issue”, Information &

Culture, 55(1), pp. 1-9.

Campbell-Kelly and Aspray 1986 Campbell-Kelly, M., and Aspray, W. (1986) Computer: A history

of the information machine. HarperCollins.

Chun 2008 Chun, W.H.K. (2008) “On

sourcery and source codes”, in Programmed Visions:

Software and Memory, pp. 19-54.

Daston 2018 Daston, L. (2018) “Calculation and the division of labor, 1750-1950”, Bulletin of the German Historical Institute. pure.mpg.de.

Eck 2000 Eck, D. (2000) The most

complex machine: A survey of Computers and Computing. A.K. Peters.

Ensmenger 2010 Ensmenger, N. (2010) The computer boys take over: Computers, programmers, and the

politics of technical expertise. MIT Press.

Essinger 2014 Essinger, J. (2014) Ada's algorithm: How Lord Byron's daughter Ada Lovelace launched the

digital age. Melville House.

Forbes-Macphail 2016 Forbes-Macphail, I.

(2016) “'I shall in due time be a poet': Ada Lovelace's poetical

science in its literary context”, in Ada's Legacy:

Cultures of Computing from the Victorian to the Digital Age, pp.

143-168.

Fuegi and Francis 2003 Fuegi, J., and Francis, J.

(2003)

“Lovelace & Babbage and the creation of the 1843

‘Notes’”,

IEEE Annals of

the History of Computing, 25(4), pp. 16-26. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1109/MAHC.2003.1253887

Galvan 2010 Galvan, J. (2010) The sympathetic medium: Feminine channeling, the occult, and communication

technologies, 1859-1919. Cornell University Press.

Gitelman 1999 Gitelman, L. (1999) Scripts, grooves, and writing machines: Representing technology in

the Edison era. Stanford University Press.

Goldstine and Van Neumann 1947 Goldstine, H.H.,

and Von Neumann, J. (1947) “Planning and coding problems for an

electronic computing instrument”, Report on the

Mathematical and Logical Aspects of an Electronic Computing Instrument Part

II, Vol. 1. Institute for Advanced Study.

Hayles 2010 Hayles, N.K. (2010) My mother was a computer: Digital subjects and literary texts. University

of Chicago Press.

Hicks 2017 Hicks, M. (2017) Programmed inequality: How Britain discarded women technologists and lost its

edge in computing. MIT Press.

Hollingsm Martin, and Rice 2018 Hollings, C.,

Martin, U., and Rice, A. (2018) Ada Lovelace: The Making of a

Computer Scientist. Bodleian Library.

Hou Je Bek 2008 Hou Je Bek, W.

(2008) “Loop”, in M. Fuller (ed.) Software Studies: A Lexicon. MIT Press.

Kittler 1990 Kittler, F.A. (1990) “Queen's sacrifice”, in Discourse

Networks 1800/1900. Translated by M. Metteer. Stanford University

Press.

Kittler 1999 Kittler, F.A. (1999) Gramophone, film, typewriter. Translated by G.

Winthrop-Young and M. White. Stanford University Press.

Kreilkamp 2005 Kreilkamp, I. (2005) “Speech on paper: Charles Dickens, Victorian phonography, and the

reform of writing”, in Literary

Secretaries/Secretarial Culture, pp. 13-31. Routledge.

Lardner 1834 Lardner, D. (1834) “Babbage's calculating engine”, Edinburgh

Review, 59, pp. 263-327.

Lovelace 1843 Menabrea, L.F., and Lovelace, A.

(1843) “Sketch of the analytical engine invented by Charles

Babbage”, Taylor's Scientific Memoirs, pp.

666-731.

Misa 2016 Misa, T.J. (2016) “Charles Babbage, Ada Lovelace, and the Bernoulli numbers”, in Ada's Legacy: Cultures of Computing from the Victorian to the

Digital Age, pp. 11-31. Association for Computing Machinery.

Padua 2017 Padua, S. (2017) “Picturing Lovelace, Babbage, and the analytical engine: A cartoonist in

mathematical biography”, BSHM Bulletin: Journal of the

British Society for the History of Mathematics, 32(3), pp. 214-220.

Plant 1995 Plant, S. (1995) “The

future looms: Weaving women and cybernetics”, Body

& Society, 1(3-4), pp. 45-64.

Plant 1997 Plant, S. (1997) Zeros

+ Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture. Fourth Estate.

Price 2003 Price, L. (2003) “From

ghostwriter to typewriter: Delegating authority at fin de siècle”, in R.J.

Griffin (ed.) The Faces of Anonymity: Anonymous and Pseudonymous

Publication from the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century. Palgrave

Macmillan.

Price and Thurschwell 2005 Price, L., and Thurschwell,

P. (2005) “Invisible hands”, in Literary Secretaries/Secretarial Culture, pp. 1-12. Routledge.

Priestley 2011 Priestley, M. (2011) “Babbage's engine”, in A Science of

Operations. Springer.

Stabler 2017 Stabler, J. (2017) “1816 in the manuscripts of Lord Byron and Mary Shelley”, Keats-Shelley Journal, 66, pp. 55-76.

Stein 1985 Stein, D. (1985) Ada:

A life and a legacy. The MIT Press.

Target 2020 Target, S. (2020) Interview by Z.M. Mann.

Video call.

Terras and Nyhan 2016 Terras, M., and Nyhan, J.

(2016) “Father Busa's female punch card operatives”, in

Debates in the Digital Humanities, pp. 60-65.

University of Minnesota Press.

Thurschwell 2001 Thurschwell, P. (2001) Literature, Technology and Magical Thinking, 1880-1920.

Cambridge University Press.

Toole 1998 Toole, B.A. (1998) Ada, the enchantress of numbers: Prophet of the computer age, a pathway to the

21st Century. Critical Connection.

Turing 1986 Turing, A.M. (1986) “Proposal for development in the mathematics division of an automatic computing

engine (ACE)”, in B.E. Carpenter and R.W. Doran (eds.) A. M. Turing's ACE Report of 1946 and Other Papers, pp. 38-39. MIT

Press.

Turing 1995 Turing, A.M. (1995) “Lecture to the London Mathematical Society on 20 February 1947”, MD COMPUTING, 12, pp. 390-390.

Turing 2009 Turing, A.M. (2009) “Computing machinery and intelligence”, in Parsing the

Turing Test, pp. 23-65. Springer.

Whitson 2015 Whitson, R. (2015) “Critical making in the digital humanities”, in Introducing Criticism in the 21st Century, pp. 157-176. Edinburgh

University Press.