Abstract

Code, the symbolic representation of computer instructions driving software, has long

been a part of research methods in literary scholarship. However, the bespoke code

of

data and computationally inflected Digital Humanities research is not always a part

of the final publication. We emphasize the need to elevate code from its generally

invisible status in scholarly publications and make it a visible research output.

We

highlight the lack of conventions and practices for theorizing, critiquing, and peer

reviewing bespoke code in the humanities, as well as the insufficient support the

dissemination and preservation of code in scholarly publishing. We introduce “defactoring” as a method for analyzing and reading code used

in humanities research and present a case study of applying this technique to a

publication from literary studies. We explore the implications of code as methodology

made material, advocating for a more integrated and computationally informed mode

of

interacting with scholarship. We conclude by posing questions about the potential

benefits and challenges of linking code and theoretical exposition to foster a more

robust scholarly dialogue.

Introduction

Code, the symbolic representation of computer instructions driving software, has long

been a part of research methods in literary scholarship. While it is a tired cliché

to point to the work of Father Busa and his compatriots at IBM as foundational work

in this respect, it was indeed a very early and important application of computation

as a means of analyzing literature [

Jones 2016]

[

Nyhan and Flinn 2016]. In more recent examples we find researchers using

computational code to calculate geo-references for a large corpus of folklore stories

[

Broadwell and Tangherlini 2012], or to seek linguistic identifiers that signal

“conversional reading”

[

Piper 2015]. However, we ask: Where is the code associated with these

works? Currently retrieving the purpose built, one-off, bespoke codebases that enable

such feats of computational literary analysis is in most scholarly domains more a

stroke of luck than the guaranteed result of responsible scholarly behavior,

scientific accountability, critical review, or academic credit. Sometimes we have

codebases. Such as in the case of Scott Enderle (2016) who crucially contributed to

a

methodological discussion about perceived

“fundamental narrative

arcs” from sentiment data in works of fiction [

Enderle 2016]. Or in the case of Kestemont et al.’s

“Lemmatization for

variation-rich languages using deep learning”

[

Kestemont et al. 2017]. However, much of the code used in the long history

of humanities computing and recent digital humanities has not been adequately

reviewed nor recognized for its importance in the production of knowledge.

In this article, we argue that bespoke code cannot be simply regarded as the

interim-stage detritus of research; it is an explicit codification of methodology

and

therefore must be treated as a fundamental part of scholarly output alongside figures

and narrative prose. The increased application of code both as a means to create

digital cultural artifacts and as an analytical instrument in humanities research

warrants the necessity to elevate code out of its invisibility in the research

process and into visible research outputs. The current system and practices of

scholarly publishing do not adequately accommodate the potential of code in

computational work — although it is a lynchpin of the discourse as both the

explication and execution of method, the code itself is not presented as part of the

discourse. We posit that its methodological and rhetorical role in the evolving

epistemology of literary studies (and the humanities in general) warrants a more

overt inclusion of code-as-method in the scholarly discourse.

The current systems of scholarly communication are not tailored very well to such

inclusion. In the humanities, there are no set conventions for theorizing,

critiquing, interrogating, or peer reviewing bespoke code. Nor are there agreed upon

methods on how to read and understand code as a techno-scholarly object. Finally,

widespread conventions and infrastructure of scholarly publishing do not support the

dissemination and preservation of code as part of the scholarly record. But given

the

increasing role of code and coding in computational and data-intensive humanities

research, this absence is increasingly becoming a deficit in the scholarly process

requiring urgent attention and action.

This article is a first step towards investigating solutions to the problems laid

out

above. More specifically we develop one possible method for reading and interrogating

the bespoke code of computational research. Modern computing is possible

because of an enormous infrastructure of code, layers upon layers of accumulated

operating systems, shared libraries, and software packages. Rather than following

every codified thread and unravelling the many layered sweater of software, we focus

on the bespoke code associated with a single scholarly publication. That

is, the code written and executed in the pursuit of a specific and unique research

output, not general-purpose libraries or software packages; the code that runs only

once or maybe a few times in the context of a specific research question.

The method we present for the critical study of bespoke code used in humanities

research is called defactoring. Defactoring is a technique for analyzing

and reading code used in computational and data-intensive research.

In a supplement to this article on GitHub, we apply this technique to the code

underlying a publication in the field of literary studies by Ted Underwood and Jordan

Sellers named

“The Longue Duree of

Literary Prestige” (2016). This analysis of their work was

made possible by the fact that — rather contrary to current convention — Underwood

and Sellers released preprints and published their bespoke code on both Zenodo [

Underwood 2015] and GitHub [

Underwood 2018]. Building

upon their informally published work, we produced a computational narrative in the

form of a Jupyter Notebook documenting our experience studying and interrogating the

code. From the supplementary

“close reading” of Underwood

and Sellers’s code, we discuss and reflect upon their work and on defactoring as an

approach to the critical study of code.

On the epistemological level, this article subsequently questions how useful it is

that conventional scholarly literacy, means of critique, and publications conventions

keep in place and even enforce a strong separation between the realm of the scholarly

publication and the realm of code, if both are expressions of the same. We contend

that these walls of separation can and should be broken down, and that this is one

of

the primary tasks and responsibilities of critical code studies. To this end, we need

to examine the effects and affordances of disrupting and breaking these boundaries.

This article and supplementary materials are an attempt to create an instance of such

a disruption. What would it look like if we linked quotidian code to loftily

theoretical exposition to create a complementary discursive space? How does this new

computationally inflected mode of discourse afford a more robust scholarly dialogue?

What may be gained by opening up bespoke code and having multiple discussions — the

literary interpretative and, the computationally methodological — simultaneously?

Background: Being Critical about Code in Literary Scholarship

According to various scholars (e.g. [

Burgess and Hamming 2011]

[

Clement 2016]) there is a dichotomy between on the one hand a

“pure” intellectual realm associated with scholarly writing and

academic print publication, and on the other hand the

“material

labour” associated with the performance of the pure intellectual realm,

for example, instrument making or programing. On closer inspection, such a dichotomy

turns out to be largely artificial. For their argument, Burgess, Hamming, and Clement

refer to the earlier work of Bruno Latour (1993) who casts the defining

characteristic of modernity as a process of

“purification” aiming

to contrast the human culture of modernity to nature [

Latour 1993].

Burgess and Hamming observe a congruent process in academia:

“Within the academy we see these processes of purification and mediation at work,

producing and maintaining the distinction between intellectual labor and material

labor, both of which are essential to multimedia production” (burgess,

2011, ¶11). This process serves to distinguish between scholarly and non-scholarly

activities:

The distinction between intellectual and material

labor is pervasive throughout scholarly criticism and evaluation of media forms.

[…] In addition, any discussion of scholarly activities in multimedia formats are

usually elided in favor of literary texts, which can be safely analyzed using

traditional tools of critical analysis. [Burgess and Hamming 2011, ¶12].

However, as Burgess and Hamming note, this distinction is based upon a

technological fallacy already pointed out by Richard Grusin in 1994. Grusin argued

that Hypertext has not changed the essential nature of text, as writing has always

already been hypertextual through the use of indices, notes, annotations, and

intertextual references. To assume that the technology

of Hypertext has revolutionarily unveiled or activated the associative nature of text

amounts to the fallacy of ascribing the associative agency of cognition to the

technology, which however is of course a

“mere” expression of that

agency.

To assume an intellectual dichotomy between scholarly publication resulting from

writing versus code resulting from programming, is a similar technological fallacy.

To assert that scholarship is somehow bound to print publication exclusively is akin

to the ascribing of agency to the technology of written text, because such an

understanding of scholarship presupposes that something is scholarship because it

is

in writing, that writing makes it scholarship. But obviously, publication is a

function of scholarship and scholarship is not a function of publication, because

scholarship does not arise from publication but is “merely”

expressed through it.

If scholarship expresses anything through publication it is argument, which is — much

more than writing — an essential property of scholarship. But in essence, it does

not

matter how, or by which form, the argument is made — whether it is made through

numbers, pictures, symbols, words, or objects. Those are all technologies that enable

us to shape and express an argument. This is not to say that technologies are mere

inert and neutral epistemological tools; different technologies shape and affect

argument in different ways. Technological choices do matter, and different

technologies can enrich scholarly argument. Producing an argument requires some

expressive technology, and the knowledge and ability to wield that technology

effectively, which in the case of writing is called

“literacy”. As

Alan Kay observed, literacy is not just gaining a fluency in technical skills of

reading and writing; it also requires a

“fluency in higher level

ideas and concepts and how these can be combined” (kay, 1993, 83). This

fluency is both structural and semantic. In the case of writing as technology, it

is

for instance about sentence structure, semantic cohesion between sentences, and about

how to express larger ideas by connecting paragraphs and documents. These elements

of

literacy translate to the realm of coding and computing [

Vee 2013]

[

Vee 2017] where fluency is about the syntax of statements and how to

express concepts, for instance, as object classes, methods and functions that call

upon other programs and data structures to control the flow of computation. Text and

writing may still be the most celebrated semiotic technologies to express an

argument, but computer code understood as

“just another” literacy

[

Knuth 1984]

[

Kittler 1993]

[

Vee 2013]

[

Vee 2017] means it can thus equally be a medium of scholarly

argument. We start from this assertion that coding and code — as the source code of

computer programs that is readable to humans and which drives the performative nature

of software [

Ford 2015]

[

Hiller 2015] — can be inherent parts of scholarship or even

scholarship by itself. That is: We assert that code can be scholarly, that coding

can

be scholarship, and that there is little difference between the authorship of code

or

text [

Van Zundert 2016].

There are two compelling reasons why code should be of interest to scholars. Much

has

been written about the dramatic increase of software, code, and digital objects in

society and culture over the last decades often with a lamenting or dystopian view

[

Morozov 2013]

[

Bostrom 2016]. But aside from doomsday prognostications, there is

ample evidence that society and its artifacts are increasingly also made up of a

“digital fabric”

[

Jones 2014]

[

Berry 2014]

[

Manovich 2013]. This means that the object of study of humanities

scholars is also changing — literature, texts, movies, games, and music increasingly

exist as digital data created through software (and thus code). This different fabric

is also branching off cultural objects with different and new properties, for

instance in the case of electronic literature and storytelling in general [

Murray 2016]. It is thus crucial for scholars studying these new forms

of humanistic artifacts to have an understanding of how to read code and the

computational processes it represents. Furthermore, as code and software are

increasingly part of the technologies that humanities scholars employ to examine

their sources — examples of this abound (e.g. [

Van Dalen-Oskam and Van Zundert 2007]

(broadwell, 2012), [

Piper 2015]

[

Kestemont et al. 2015], etc.) — understanding the workings of code is

therefore becoming a prerequisite for a solid methodological footing in the

humanities.

As an epistemological instrument, code has the interesting property of representing

both the intellectual and material labor of scholarly argument in computational

research. Code affords method not as a prosaic, descriptive abstraction, but as the

actual, executable inscription of methodology. However, the code underpinning the

methodological elements of the scholarly discourse are themselves not presented as

elements in the discourse. Their status is akin to how data and facts are

colloquially perceived, as givens, objective and neutral pieces of information or

observable objects. But like data [

Gitelman 2013] and facts [

Betti 2015], code is

unlikely to be ever

“clean”,

“unbiased”, or

“neutral” (cf. also [

Berry 2014]).

Code is the result of a particular literacy (cf. for instance [

Knuth 1984]

[

Kittler 1993]

[

Vee 2013] (vee 2017) that encompasses the skills to read and write

code, to create and interrelate code constructs, and to express concepts, ideas, and

arguments in the various programming paradigms and dialects in existence. Like text,

code has performative properties that can be exploited to cause certain intended

effects. And also like text, code may have unintended side effects (cf. e.g. [

McPherson 2012]. Thus, code is a symbolic system with its own rhetoric,

cultural embeddedness [

Marino 2006], and latent agency [

Van Zundert 2016]. Therefore, rather than accepting code and its

workings as an unproblematic expression of a mathematically neutral or abstract

mechanism, it should be regarded as a first-order part of a critical discourse.

However, the acceptance of code as another form of scholarly argument presents

problems to the current scholarly process of evaluation because of a lack of

well-developed methods for reading, reviewing, and critiquing bespoke code in the

humanities domain. Digital humanities as a site of production of non-conventional

research outputs — digital editions, web-based publications, new analytical methods,

and computational tools for instance — has spurred the debate on evaluative practices

in the humanities, exactly because practitioners of digital scholarship acknowledge

that much of the relevant scholarship is not expressed in the form of traditional

scholarly output. Yet the focus of critical engagement remains on

“the fiction of ‘final outputs’ in digital

scholarship”

[

Nowviskie 2011], on old form peer review [

Antonijević 2015], and on approximating equivalencies of digital

content and traditional print publication [

Presner 2012]. Discussions

around the evaluation of digital scholarship have thus

“tended to

focus primarily on establishing digital work as equivalent to print publications

to make it count instead of considering how digital scholarship might transform

knowledge practices” [

Purdy and Walker 2010, 178] [

Anderson and McPherson 2011]. As

a reaction, digital scholars have stressed how peer review of digital scholarship

should foremost consider how digital scholarship is different from conventional

scholarship. They argue that review should be focussed on the process of developing,

building, and knowledge creation [

Nowviskie 2011], on the contrast and

overlap between the representationality of conventional scholarship and the strong

performative aspects of digital scholarship [

Burgess and Hamming 2011], and on the

specific medium of digital scholarship [

Rockwell 2011].

The debate on peer review of digital output in digital scholarship might have

propelled a discourse on the critical reading of code. However, the debate geared

almost completely towards high level evaluation, concentrating for instance on the

issue of how digital scholarship could be reviewed in the context of promotion and

tenure track evaluations. Very little has been proposed as to concrete techniques

and

methods for the practical critical study of code as scholarship in scholarship.

[1]

Existing guidance pertains to digital objects such as digital editions [

Sahle and Vogeler 2014] or to code as cultural artefact [

Marino 2006], but no substantial work has been put forward on how to read, critique, or

critically study bespoke scholarly code. We are left with the rather general

statement that

“traditional humanities standards need to be part

of the mix, [but] the domain is too different for them to be applied without

considerable adaptation”

[

Smithies 2012] and the often echoed contention that digital artifacts

should be evaluated

in silico as they are and not as to how

they manifest in conventional publications [

Rockwell 2011]

In what went before, we hope to have shown and argued that bespoke code developed

specifically in the context of scholarly research projects should be regarded as

first class citizens of the academic process. As scholars, we need methods and

techniques to critique and review such code. We posit that developing these should

be

an objective central to critical code studies. As a gambit for this development in

what follows we present defactoring as one possible method.

Towards a Practice of Critically Reading Bespoke Scholarly Code

Beyond the theoretical and methodological challenges, reading and critically studying

code introduces practical challenges. Foremost is the problem of determining what

code is actually in scope for these practices. The rabbit hole runs deep as research

code is built on top of standard libraries, which are built on top of programming

languages, which are built on top of operating systems, and so on. Methodologically,

a boundary must be drawn between the epistemologically salient code and the context

within which it executes. [

Hinsen 2017] makes a useful distinction

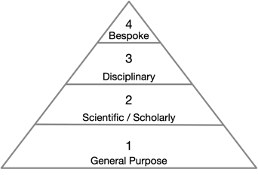

that divides scientific software into four layers.

First, there is a layer of

general software. Generalized computational

infrastructure like operating systems, compilers, and user interfaces fall into this

category. Generic tools like Microsoft Word or Apache OpenOffice or general-purpose

programming languages like Python or C, while heavily used in scientific domains,

also have a rich life outside of science (and academia more broadly). The second

layer comprises

scientific software. Applications, libraries, or

software packages that are not as general purpose as layer one, rather they are

designed for use in scientific or academic activities. For example, Stata or SPSS

for

statistical analysis, Open-MPI for parallel computing in high performance computing

applications, or Globus as a general tool for managing data transfers, AntConc for

text corpus analytics, Classical Text Editor to create editions of ancient texts,

or

Zotero for bibliographic data management. A third layer comprises

disciplinary

software, libraries for use in specific epistemological contexts for

analysis of which the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) or the Syuzhet R package for

literary analysis are excellent examples. The design of Syuzhet means it can be used

in a variety of analyses, not just the analysis performed by Jockers [

Jockers 2014]

[

Jockers 2015]. Disciplinary software is distinct from lower layers as

it embeds certain epistemological and methodological assumptions into the design of

the software package that may not hold across disciplinary contexts. Lastly, there

is

a fourth layer of

bespoke software. This layer comprises project

specific code developed in pursuit of the very specific set of tasks associated with

one particular analysis. This is the plumbing connecting other layers together to

accomplish a desired outcome. Unlike the previous layers, this code is not meant to

be generalized or reused in other contexts.

As argued above: with increasing frequency project specific

bespoke code

is created and used in textual scholarship and literary studies (cf. for instance

[

Enderle 2016]

[

Jockers 2013]

[

Piper 2015]

[

Rybicki et al. 2014]

[

Underwood 2014]

[

Lahti et al. 2020]. The algorithms, code, and software underpinning the

analyses in these examples are not completely standardized

“off the

shelf” software projects or tools. These codebases are not a software

package such as AntConc that can be viewed as a generic distributable tool. Instead,

these codebases are (in Hinsen’s model) the fourth layer of bespoke code: They are

one-off highly specific and complex analytical engines, tailored to solving one

highly specific research question based on one specific set of data. Reuse,

scalability, and ease-of-use are — justifiably [

Baldridge 2015] — not

specific aims of these code objects. This is code meant only to run a limited number

of times in the context of a specific project or its evaluation.

The words, prose, and narrative of a scholarly article are an expression of a

rhetorical procedure. When critically engaging with a scholarly article, the focus

is

on the underlying argument and its attending evidence. Scholarly dialectic pertains

not to the specifics of the prose, the style of writing, or the sentence structure.

One could argue, paying attention to the details of code is equivalent to paying

attention to wordsmithing and thus missing the forest for the trees, that is,

fetishizing the material representation at the expense of the methodological

abstraction. However, the significant difference is that the words are plainly

visible to any and all readers, whereas the code is often hidden away in a GitHub

repository (if we are lucky) or on a drive somewhere in a scholar’s office or

personal cloud storage. We argue that the computational and data driven arguments

are

missing the material expression (the code) of their methodological procedures. The

prosaic descriptions currently found in computational literary history and the

digital humanities are not sufficient. Notwithstanding their admirable aims and

objectives platforms where one would expect bespoke code bases to be in focus for

primary attention and publication (such as, for instance,

Cultural Analytics

[2] and

Computational Humanities Research)

[3] do not provide standardized access to code or code repositories related to

publications. Nor do they enforce the open publication of such research output. If

the prose is an expression of the argument, with charts and numbers and models as

evidence, then the code, which is the expression of the methodological procedures

that produced the evidence, is just as important as the words. Our thinking is not

unlike Kirschenbaum’s (2008) forensic approaches to writing in that just as digital

text has a material trace, methodological analysis also has a materiality inscribed

in code [

Kirschenbaum 2008]. However, we perhaps go farther to argue

these inscriptions should be surfaced in publication. Why write an abstract prosaic

description of methodological procedures divorced from the codified expression of

those procedures? Why not interweave or link both types of expression more fully and

more intrinsically?

Defactoring

We introduce an experimental technique called

defactoring to address the

challenges of critically reading and evaluating code. We expand on ideas of [

Braithwaite 2013] who considered defactoring as the process of

de-modularizing software to reduce its flexibility in the interest of improving

design choices. This is counter intuitive to software engineering best practices,

which prefer increased generalization, flexibility, and modularization. Refactoring

and software engineering emphasize writing code that can be managed according to the

organizational labor practices of software production and object-oriented design,

breaking blocks of code into independent units that can be written and re-used by

teams of developers (cf. for instance [

Metz and Owen 2016]. While these best

practices make sense for code intended for Hinsen's first three layers of software,

the fourth layer, bespoke code, might better have a different style with less

emphasis on abstraction and modularity because such code becomes harder to read as

a

narrative.

Here, we are interested in elucidating what a process of defactoring code looks like

for the purposes of critically assessing code, which implies reading code. In our

expanded notion of the concept, defactoring can be understood as a close reading of

source code — and if necessary a reorganization of that code — to create a narrative

around the function of the code. This technique serves multiple purposes: critically

engaging the workings and meanings of code; peer reviewing code; understanding the

epistemological and methodological implications of the inscribed computational

process; and a mechanism for disseminating and teaching computational methods. We

use

defactoring to produce what might prospectively be called the first critical edition

of source code in the digital humanities by unpacking Ted Underwood and Jordan

Sellers’s code associated with their article

“The Longue Duree of Literary Prestige”

(underwood-sellers, 2016a).

[4]

The codebase that Underwood and Sellers produced and that underpins their argument

in

“The Longue Duree of Literary

Prestige” is a typical example of multi-layered code. The code written by

Underwood and Sellers is bespoke code, or fourth layer code in Hinsen’s model of

scientific software layers. When dealing with a scholarly publication such as “The Longue Duree of Literary

Prestige” , our reading should concentrate on layer four, the bespoke code.

The code from the lower layers, while extremely important, should be evaluated in

other processes. As Hinsen points out, layer four software is the least likely to

be

shared or preserved because it is bespoke code intended only for a specific use case;

this means it most likely has not been seen by anyone except the original authors.

Lower layer software, such as scikit-learn, has been used, abused, reviewed, and

debugged by countless people. There is much less urgency therefore to focus the kind

of intense critical attention that comes with scholarly scrutiny on this software

because it already has undergone so much review and has been battle tested in actual

use.

There is no established definition of defactoring or its practice. We

introduce defactoring as a process for “close reading” or possibly

a tool for “opening the black box” of computational and data

intensive scholarship. While it shares some similarity to the process of refactoring

— in that we are “restructuring existing computing code without

changing its external behavior” — refactoring restructures code into

separate functions or modules to make it more reusable and recombinable. Defactoring

does just the opposite. We have taken code that was broken up over several functions

and files and combined it into a single, linear narrative.

Our development of defactoring as a method of code analysis is deeply imbricated with

a technical platform (just as all computational research is). But rather than pushing

the code into a distant repository separate from the prosaic narrative, we compose

a

computational narrative

[

Perez and Granger 2015] — echoing Knuth’s literate programming (1984) — whereby

Underwood and Sellers’s data and code are bundled with our expository descriptions

and critical annotations. This method is intimately intertwined with the Jupyter

Notebook platform which allows for the composition of scholarly and scientific

inscriptions that are simultaneously human and machine readable. The particular

affordances of the Notebook allow us to weave code, data, and prose together into

a

single narrative that is simultaneously readable and executable. Given our goals to

develop a method for critically engaging computational scholarship, it is imperative

we foreground Underwood and Sellers’s bespoke code, and the Jupyter Notebooks enables

us to do so.

Pace of Change

The bespoke code we defactor is that which underlies an article that Underwood and

Sellers published in

Modern Language Quarterly (MLQ)

[

Underwood and Sellers 2016a]:

“The Longue

Durée of Literary Prestige.” This article was the culmination

of prior work in data preparation [

Underwood and Sellers 2014], coding

[

Underwood and Sellers 2015]

[

Underwood 2018]

[

Underwood 2018] preparatory analysis [

Underwood and Sellers 2015]. The main thrust of the MLQ article seems to be

one of method:

Scholars more commonly study reception by

contrasting positive and negative reviews. That approach makes sense if you’re

interested in gradations of approval between well-known writers, but it leaves out

many works that were rarely reviewed at all in selective venues. We believe that

this blind spot matters: literary historians cannot understand the boundary of

literary distinction if they look only at works on one side of the boundary. [Underwood and Sellers 2016a, 324]

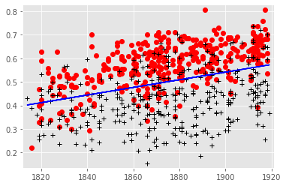

To substantiate their claim, Underwood and

Sellers begin their

“inquiry with the hypothesis that a widely

discussed ‘great divide’ between elite literary culture and the

rest of the literary field started to open in the late nineteenth century.”

To this end, they compare volumes of poetry that were reviewed in elite journals in

the period 1820–1917 with randomly sampled volumes of poetry from the HathiTrust

Digital Library from the same period. They filtered out volumes from the HathiTrust

resource that were written by authors that were also present in the reviewed set,

effectively ending up with non-reviewed volumes. In all, they compare 360 volumes

of

“elite” poetry and 360 non-reviewed volumes. For each volume,

the relative frequencies of the 3200 most common words are tallied and they apply

linear regression to these frequency histograms. This linear regression model enables

them finally to predict whether a sample that was not part of the regression data

would have been reviewed or not. The accuracy of their predictions turn out to be

between 77.5 and 79.2 percent. This by itself demonstrates that there is some

relationship between some poetry volume’s vocabulary and that volume being reviewed.

But more importantly, what they can glean from their results is that the traditional

idea that literary fashions are pretty stable over some decades and are then

revolutionized towards a new fashion deserves revisiting: The big 19th century divide

turns out not to be a revolutionary change but a stable and slowly progressing trend

since at least since 1840. Underwood and Sellers conclude:

None

of our “models can explain reception perfectly, because

reception is shaped by all kinds of social factors, and accidents, that are not

legible in the text. But a significant chunk of poetic reception can be

explained by the text itself (the text supports predictions that are right

almost 80 percent of the time), and that aspect of poetic reception remained

mostly stable across a century” (underwood-sellers, 2016b)

Sudden changes also do not emerge if they try to predict other social categories like

genre or authorial gender. They finally conclude that the question of why the general

slow trend they see exists is too big to answer from these experiments alone, because

of the many social factors that are involved.

Underwood and Sellers purposely divided their code into logical and meaningful parts,

modules, and functions stitched together into a data processing and analysis script.

We found to better understand the code as readers (vs. authors) and therefore

necessary to restructure, defactor, the code into what is usually understood as a

poor software engineering practice, namely making a single long, strongly integrated,

procedural process. This makes the code a linear narrative, which is easier for

humans to read while the computer is, for the most part, indifferent. There is a

tension between these two mutually exclusive representations of narratives with code

divided and branched, emerging from the process of development by software engineers,

and with prose as a linear narrative intended for a human reader. What we observed

is

that the processes of deconstructing literature and code are not symmetrical but

mirrored. Where deconstructing literature usually involves breaking a text apart into

its various components, meanings, and contexts, deconstructing software by

defactoring means integrating the code’s disparate parts into a single, linear

computational narrative. “Good code,” in other words, is

already deconstructed (or “refactored”) into modules and

composable parts. For all practical purposes we effectively are turning “well engineered” code into sub-optimal code full of

“hacks” and terrible “code smells” by

de-modularizing it. However, we argue, this “bad” code is easier

to read and critique while still functioning as its authors intended.

Defactoring injects the logical sections of the code, parts that execute steps in

the

workflow, with our own narrative reporting on our understanding of the code and its

functioning at that moment of the execution. The Jupyter Notebook platform makes this

kind of incremental exploration of the code possible and allows us to present a fully

functioning and executable version of Underwood and Sellers’s code that we have

annotated. Reading (and executing along the way) this notebook therefore gives the

reader a close resemblance of the experience of how we as deconstructionists

“closely read” the code.

[5]

Defactoring Pace of Change Case Study

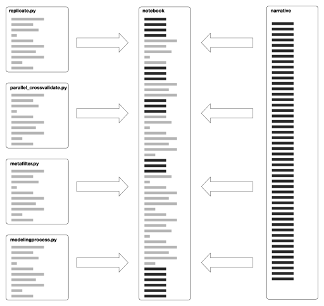

As a supplement to this article, we have included our example defactoring of

Underwood and Sellers’ Pace of Change code. We have forked their Github repository

and re-worked their code into a Jupyter notebook. Conceptually, we combined their

Python code files with our narrative to create a computational narrative that can

be

read or incrementally executed to facilitate the exploration of their computational

analysis (illustrated in Figure 2).

The defactored code is available in the following GitHub repository:

https://github.com/interedition/paceofchange

Readers are strongly encouraged to review the notebook on GitHub or download and

execute it for an even richer, interactive experience. Here we want to highlight two

specific examples within the code of Underwood and Sellers that in our reading of

the

code became rather significant.

# vocablist = binormal_select(vocablist, positivecounts, negativecounts, totalposvols, totalnegvols, 3000)

# Feature selection is deprecated. There are cool things

# we could do with feature selection,

# but they'd improve accuracy by 1% at the cost of complicating our explanatory task.

# The tradeoff isn't worth it. Explanation is more important.

# So we just take the most common words (by number of documents containing them)

# in the whole corpus. Technically, I suppose, we could crossvalidate that as well,

# but *eyeroll*.

Underwood and Seller's code above does not actually perform any work as each line

has

been commented out; however, we include it because it points towards an execution

path not taken and an interesting rationale for why it was not followed. In the

“production” code, the heuristic for feature selection

is to simply select the 3200 most common words by their appearance in the 720

documents. This is a simple and easy technique to implement and — more importantly

—

explain to a literary history and digital humanities audience. Selecting the top

words is a well-established practice in text analysis, and it has a high degree of

face validity. It is a good mechanism for removing features that have diminishing

returns. However, the commented code above tells a different, and methodologically

significant, story. The comment discusses an alternative technique for feature

selection using binormal selection. Because this function is commented out and not

used in the analysis, we have opted to not include it as part of the defactoring.

Instead, we have decided to focus on the more interesting rationale about why

binormal selection is not being used in the analysis as indicated in the comments:

There are cool things we could do with feature selection, but

they'd improve accuracy by 1% at the cost of complicating our explanatory task.

The tradeoff isn't worth it. Explanation is more important.

This comment

reveals much about the reasoning, the effort, and energy focused on the important,

but in the humanities oft neglected, work of discussing methodology. As Underwood

argued in

The literary uses of high-dimensional space

[

Underwood 2015], while there is enormous potential for the application of

statistical methods in humanistic fields like literary history, there is resistance

to these methods because there is a resistance to methodology. Underwood has

described the humanities disciplines relationship to methodology as an

“insistence on staging methodology as ethical struggle”

[

Underwood 2013]. In this commented code , we can see the material

manifestation of Underwood's methodological sentiment, in this case embodied by

self-censorship in the decision to not use more statistically robust techniques for

feature selection. We do not argue this choice compromises the analysis or final

conclusions, rather we want to highlight the practical and material ways research

methods are not a metaphysical abstraction, but rather have a tangible and observable

reality. By focusing on a close reading of the code and execution environment, by

defactoring, we illuminate methodology and its relation to the

omnipresent

explanatory task commensurate with the use of

computational research methods in the humanities.

The Croakers

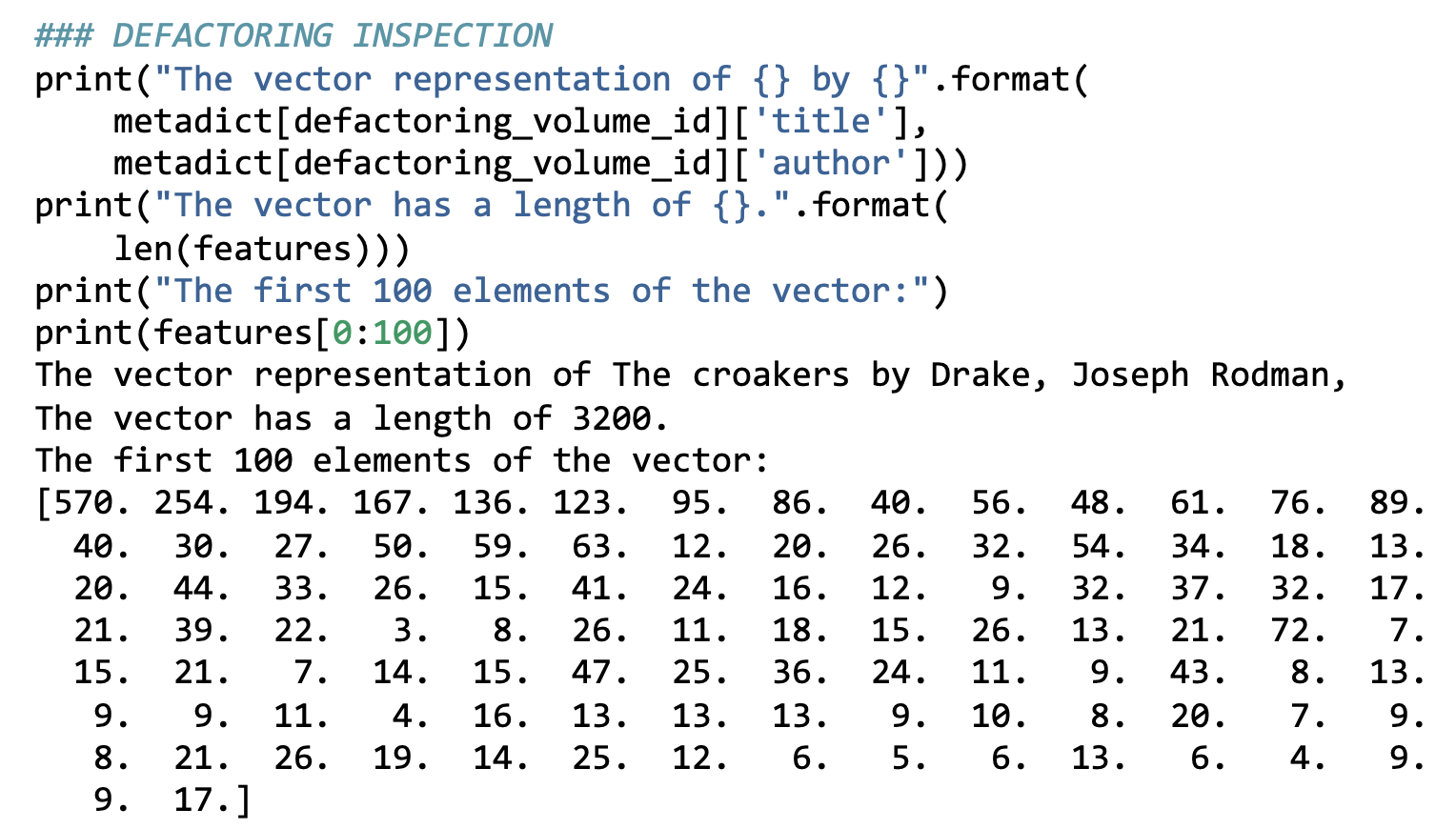

At this point, any prosaic resemblance left in the data is gone and now we are

dealing entirely with textual data in a numeric form.

The code output above shows us a single volume processed by the code, The Croakers by Joseph Rodman Drake. As we can see, the words

are now represented as a list of numbers (representing word frequencies). However,

this list of numbers still requires additional transformation in order to be

consumable by a logistic regression. The word frequencies need to be normalized so

they are comparable across volumes. To do this, Underwood and Sellers divide the

frequency of each individual word by the total number of words in that volume. This

makes volumes of different lengths comparable by turning absolute frequencies into

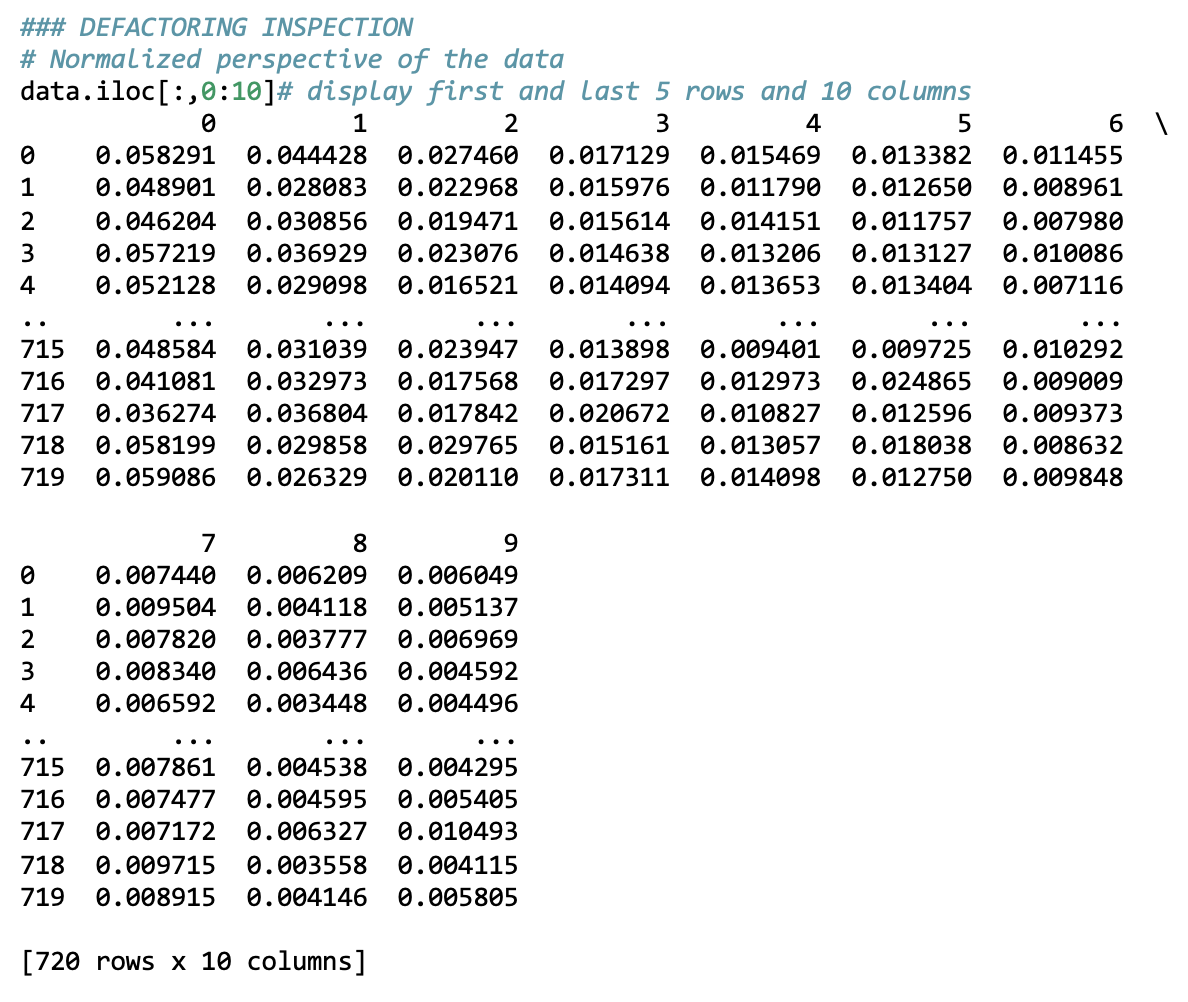

relative frequencies. The code output below shows the normalized frequency values

for

10 columns (10 words) of the last 5 poetry volumes.

The last row in code listing 2 (the row starting with the number 719) is the

normalized representation of The Croakers by Joseph

Rodman Drake. It is one of 720 relatively indistinguishable rows of numbers in this

representation of 19th century poetry. This is a radical transformation of the

original, prosaic representation literary historians are probably used to seeing

(shown in Figure 3) and that would be the subject of close reading. What we can see

here is the contrast between representations for close and distant reading

side-by-side.

Discussion

The story told by the Defactoring Pace of Change

case-study is that of methodological data transformation through a close reading and execution of bespoke code. The code is an

engine of intermediate representations, meaning the computational narrative

told by Defactoring Pace of Change is one of cleaning, shaping, and restructuring

data; transformation of poetry into data (and metadata), of large data into small

data, and finally of data into visualizations. The Code is a material record, a

documentary residue, of Underwood and Sellers’ methodology.

Representations of Data in and Through Code

From the perspective of data, the code of Pace of Change is not the beginning. The

project begins with a collection of prepared data and metadata from poetry volumes

transformed into bags of words [

Underwood 2014]. There was a

significant amount of

“data-work” completed before Pace of Change

began, but just as bespoke code is built on shared libraries, operating systems, and

general purpose programming languages, the

bespoke data is built on

previous data and data work. Both the data and code included in Pace of Change are

products derived from larger

“libraries” (both in the sense of

software libraries like scikit-learn and digital libraries like HathiTrust). The

OCR’d texts in the HathiTrust digital library are akin to the general purpose

programming languages or operating systems; digital collections have many uses.

[6] The content and context of the poetry data before their use in the

Pace of Change analysis are salient and important; data are the

result of socio-technical processes [

Chalmers and Edwards 2017]

[

Gitelman 2013]. Defactoring focuses on the intimate relationship

between the bespoke-data, bespoke-code, and the environment within which computations

occur.

The data in Pace of Change are not one thing, but rather a set of things undergoing

a

series of interconnected renderings and transformations. As we see in The Croakers example above, poetry starts as a tabular

collection of metadata and bags of words. The code filters, cleans, identifies a

subset of the poetry data relevant to the analysis. The selected metadata then drives

the processing of the data files, the bags of words, to select the top 3,200 words

and creates a standard vectorized representation of each poetry volume and,

importantly for supervised learning, their associated labels (“reviewed” or “not reviewed” ). Much of the

bespoke data/code-work of Pace of Change is in the service of producing the

representation of the data we see in Figure 4; bespoke code for transforming bespoke

data into standardized data conformant to standardized code. What comes out the other

side of the mathematically intensive computation of Pace of Change, the logistic

regression, is more data. But these data are qualitatively and

quantitatively different because they reveal new insights, patterns, and significance

about poetry. The predictions of 720 individual statistical models for each poetry

volume, as seen in Figure 6, and the coefficients of the final statistical model are,

for Underwood and Sellers, the important representations — for it is through the

interpretation of these representations that they can find new insights about

literary history. The data story of the Pace of Change code

ends with a chart and two new CSV files. One could, theoretically, review and

critique these data, but we would argue, focusing on just the data in absence of the

code which documents their provenance would only be a small part of the story.

Even though the data, its transformations, and renderings are central to Underwood’s

and Sellers’ understanding of the pace of change of literary vocabulary, almost

nothing of this scientific material makes it to the final transformation that is

represented with the scholarly article eventually published in Modern Language Quarterly. In fact, all code and data are jettisoned from

the narrative and only a high-level prose description of the computational research

and one picture congruent with Figure 6 in this publication remain. As a full and

accountable description of the methodology, this seems rather underwhelming.

Method Made Material

Defactoring Pace of Change reveals an important methodological dynamic about the

relationship between mundane data management and urbane methodology. As the

“binormal_select()” example above shows, there were

analytical paths implemented, but ultimately not pursued. Only one of the two

feature selection methods is discussed in the MLQ article. Underwood and Sellers

chose not to use a more robust method for feature selection because they foresaw

the improved accuracy would not balance the effort required to explain it to an

audience unfamiliar with more advanced statistical expertise. There is a clear

tension, and gap, between the techniques being used and the explanation that must

accompany them. Similarly in the MLQ publication and the Figshare contribution, we

find many allusions to the tweaking of the models that Underwood and Sellers used,

but for which we do not find in the code — for instance, where they refer to

including gender as a feature [

Underwood and Sellers 2016a, 338]

and to using multi period models [

Underwood and Sellers 2016a, 329]. Traces remain of these analyses in the code but supplanted by later code and

workflows these statistical wanderings are not explicitly documented

anymore.

[7]

In all, this means that there is a lot of analysis and code-work that remains

unrepresented. Even in a radically open project such as Pace of Change, there is

still going to be code, data, and interpretive prose that does not make the final

cut (i.e. the MLQ article). Moreover, much analytic and code effort remains

invisible because it does not appear in the final code repository, leaving only an

odd trace in the various narratives. We are not arguing that all of the developmental work of scholarship be open and available, but

our defactoring of Pace of Change makes us wonder what a final, camera-ready

representation of the code produced by Underwood and Sellers would include.

The invisibility of so many parts of the research narrative signals to us the very

need for the development of a scholarly literacy and infrastructure that engages

with the bespoke code of research not as banal drudgery, but as the actual,

material manifestation of methodology. What if the annotated code, such as that

which we produced in defactoring Pace of Change, was the “methods” section? Only by such deep and intimate understanding of code

can we award credit and merit to the full analytical effort that scholars

undertake in computational explorations.

On Reading Code

This experiment in defactoring highlights a gap between the narrative of the code

and that of the MLQ article. This gap is enlarged by the current conventions of

scholarly publishing and communication that discourages including code in the

publication itself. But who really wants to read code anyway? As an invited early

reader of this work pointed out, the code is not that interesting because scholars

are primarily interested in the “underlying methodology;” an

abstract theoretical construct. But where exactly does this “underlying

methodology” obtain a material reality? In the minds of authors,

reviewers, and readers? We argue computational research creates a new discursive

space: the code articulates the underlying methodology.

There is not some metaphysical intellectual method whose material reality exists

in the noosphere. When we read code, we read methodology.

This is a radical proposition that implies a disruptive intervention in the

conventions of scholarly publishing and communication where data and

computationally intensive works are concerned. Very rarely are the data and code

incorporated directly into the prosaic narrative, and why would they? Code is

difficult to read, filled with banal boilerplate that doesn’t directly contribute

to an argument and interpretation. Furthermore, code is challenging to express in

print-centric mediums like PDFs and books. But when the documentary medium itself

becomes a platform for the manipulation and execution of the code (i.e. a web

browser and computational notebooks) then it is possible to imbricate the material

expression of methodological procedures in-line with the

prosaic representations of the rhetorical procedure.

Defactoring Pace of Change is perhaps a first,

roughshod attempt at exploring a new discursive space. We have, given the tools at

our disposal, tried to create a publication that represents what could be, and

should be, possible. However, the platforms and the practices do not exist or have

not come together to truly represent this idyllic confluence of prose, data, and

code.

Defactoring Pace of Change leverages Jupyter

Notebooks as a platform that affords the ability for both humans and machines to

read the same document, but the platforms of publishing and reading such documents

are non-existent or are immature at best. Beyond platforms, there are research and

publication practices, a set of conventions that need to emerge where code is more

seamlessly integrated into the narrative.

[8] Our reconfiguration of Underwood and Seller’s Python code

into a linear structure and the intermixing of prosaic descriptions is an

experiment in establishing new practices and conventions for computational

narratives.

Conclusion

There is a tendency both in scholars and engineers to separate things [

Bowker and Star 1999]. We can see one such separation in the TEI-XML community.

Inspired by early developments in electronic typesetting [

Goldfarb 1996], both textual scholars and engineers arrived upon the idea of separation of form

and content [

DeRose et al. 1990]: There is the textual information (

“Nixon resigns” ), and there is how that information looks

(e.g. bold large caps in the case of a newspaper heading). Thus, in TEI-XML an

unproblematic separation of information and layout is assumed. On closer inspection

however, such a separation is not as unproblematic at all [

Welch 2010]

[

Galey 2010]. Form demands to be part of meaning and interpretation as

is dramatically clear from looking at just one poem by William Blake. Yet such

separation has emerged in science and research: Data tends to be separated from

research as an analytical process, and the creation of digital research objects (such

as digital data and analytic code) goes often unrecognized as intellectual research

work and is considered

“mere” supportive material labor [

Burgess and Hamming 2011]. Data is mostly regarded as a neutral and research

independent entity, indeed something

“given” as the Latin root

suggests. That the state of data are not quite as straightforward has been argued

before [

Galey 2010]

[

Drucker 2011]

[

Gitelman 2013]. From our experience defactoring Pace of Change we

derive the same finding: There are rich stories to tell about the interactions

between code and data.

Code can be read and examined independently of its context and purpose, as a static

textual object. In such a case, one looks critically at the structure of the code

—

are separate steps of the process clearly delineated and pushed to individual

subroutines to create a clearly articulated and maintainable process; are there

considerable performance issues; have existing proven libraries been used? This kind

of criticism — we could compare it to textual criticism — is informative but in a

way

that is wholly unconnected to the context of its execution. It is like picking apart

every single cog in a mechanical clock to judge if it is well built, but without

being interested in what context and for what purpose it will tell time. This would

be code review as practiced in an industrial setting. Code review takes the

structural and technical quality of code into consideration only insofar that obvious

analytical errors should be pointed out, judged against measures of performance and

industrial scalability and maintainability. However, this approach has little

relevance for the bespoke code of scholarly productions; it is relatively

“okay for academic code to suck” as compared to the best

practices of industrial code-work [

Baldridge 2015]. But what about

best practices for

understanding the bespoke code of scholarly

research? What about critically understanding code that

“only runs

once” and whose purpose is insight rather than staying around as

reusable software? We put forth defactoring as a technique for unveiling the workings

of such bespoke code to the scholarly reader (and potentially a larger audience).

We

cast it as a form of close reading that draws out the interaction between code and

the content, the data, and the subject matter. Essentially, we think, defactoring

is

a technique to read and critique those moments of interaction. Data, analytic code,

and subject matter co-exist in a meaningful dynamic and deserve inspection. It is

at

these points that defactoring affords a scholar to ask — not unlike she would while

enacting literary criticism: What happens here and what does it mean? Whereas the

original code is mere supportive materials, the defactored and critically read code

morphs into a first-order computational narrative that elevates the documentary

residue of analysis to a critical component of the scholarly contribution.

In this sense, we found that defactoring is more than just a method to open up

bespoke code to close reading in the digital humanities. It also shows how code

literacy, just as “conventional” literacy, affords an

interpretative intellectual engagement with the work of other scholars, which is

interesting in itself. The code is an inscription of methodological choices and can

bridge the gap between the work that was done and the accounts of the work. We think

that the potential of defactoring reaches beyond the domain of digital humanities.

As

a critical method it intersects with the domains of Critical Code Studies and

Cultural Analytics as well, and could as a matter of fact, prove viable and useful

in

Science and Technology Studies or any scientific/scholarly domain where bespoke code

is used or studied.

On an epistemological level, once again it appears that we cannot carve up research

in neatly containerized independent activities of which the individual quality can

be

easily established and aggregated to a sum that is greater than the parts. The

“greater” is exactly in the relations that exist between the

various activities and that become opaque if the focus is put on what is inside the

different containers. This is why we would push even farther than saying that data

and code are not unproblematically separable entities. Indeed, we would argue that

they are both intrinsic parts of a grander story that Underwood and Sellers tell us

and which consists of several intertwined narratives: There is a narrative that is

told by the code, one that is told by the comments we found in that code, and there

is a narrative of data transformations. These narratives together become the premises

of an overarching narrative that results first as a Figshare contribution,

[9] and later as an MLQ publication. These narratives are all stacked turtles,

and they all deserve proper telling.

Quite logically, with each stacked narrative the contribution of each underlying

narrative becomes a little more opaque. The MLQ article suggests an unproblematic,

neat, and polished process of question-data-analysis-result. But it is only thanks

to

their openness that Underwood and Sellers grant us insight to peer into the gap and

see the computational process of data analysis to a presentable result. Underwood

and

Sellers went through several iterations of refining their story. The Figshare

contribution and the code give us much insight into what the real research looked

like for which the MLQ article, in agreement with Jon Claerbout’s ideas (buckheit,

1995), turns out to be a mere advertising of the underlying scholarship. In contrast

to what we argue here — that data and code deserve more exposure and critical

engagement as being integral parts of a research narrative — we observed in the

succession of narrative transformations that the aspect and contribution of code

became not only more opaque with every stacked narrative but vanished altogether from

the MLQ article. This gap is not a fault of Underwood and Sellers, but rather deeply

is embedded in the practices and expectations of scholarly publishing.

We wish to close with a pivotal reflection on our own challenges publishing this

article. Our original vision for

Defactoring Pace of Change

was to publish it as a single, extensive computational narrative that

includes both this theoretical discussion and interpretation along with the

defactored narrative of Underwood and Sellers' Python code. We wanted all of the

context, interpretation, and methodological code to be a single document; a combined

narrative readable by humans and executable by computers. However, every single

reviewer we have met has suggested that we should split up the scholarly argument

and

the defactored code, thus creating a

new gap between this

theoretical discussion you are reading and the case-study/Notebook with the actual

Defactoring Pace of Change living on another

platform. Reading the notebook is difficult, possibly mind numbing. We have done our

best to make the Pace of Change code readable and our close reading of the code

revealed many interesting aspects about data, representation, process, and

transformation. Our hope was to make an argument with the very structure and form

of

Defactoring Pace of Change by including the code as part of

the narrative. However, as one of our earlier readers pointed out, this has been a

“brilliant, glorious, provocative failure,” while we

hope to have put forth an argument about bespoke code using the standard scholarly

prosaic conventions, we have failed to challenge and change the deeply ingrained

conventions and infrastructures of scholarly publishing.

[10]

What if Underwood and Sellers' had written The Longue

Durée of Literary Prestige to include the code written in a defactored

style, that is, as a linear narrative intermixed with human-readable expository

annotations? They would have also faced the same structural challenges publishing

their article as we faced in Defactoring Pace of Change. The

conventions of scholarly publishing and structuring a scholarly narrative are not

congruent with the Computational Notebook paradigm. We do not yet have academic genre

conventions for publishing bespoke code. What would a

notebook-centric scholarly publication, one with no gap that imbricated code and

interpretation, look like? Defactoring Pace of Change is our

attempt at a provocation not only to consider the epistemological and methodological

significance of bespoke code in computational and data intensive digital humanities

scholarship, but also to consider the possibilities of computation in the expression

of such scholarship.

Works Cited

Anderson and McPherson 2011 Anderson, S., and

McPherson, T. (2011)

“Engaging digital scholarship: Thoughts on

evaluating multimedia scholarship”,

Profession, pp. 136–51. Available at:

https://doi.org/prof.2011.2011.1.136.

Antonijević 2015 Antonijević, S. (2015) Amongst digital humanists: An

ethnographic study of digital knowledge production. London, Houndmills,

New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Berry 2014 Berry, D.M. (2014) Critical theory and the digital. Critical theory and contemporary

society. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Betti 2015 Betti, A. (2015) Against facts. Cambridge Massachusetts, London England: MIT Press.

Bostrom 2016 Bostrom, N. (2016) Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Bowker and Star 1999 Bowker, G.C., and Star, S.L.

(1999) Sorting things out: Classification and its

consequences. The MIT Press.

Broadwell and Tangherlini 2012 Broadwell, P., and

Tangherlini, T.R. (2012) “TrollFinder: Geo-semantic exploration

of a very large corpus of Danish folklore”, in Proceedings of LREC. Istanbul, Turkey.

Carullo 2020 Carullo, G. (2020) Implementing effective code reviews: How to build and maintain clean

code. New York: Apress.

Cerquiglini 1999 Cerquiglini, B. (1999) In praise of the variant: A critical history of philology.

Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Chalmers and Edwards 2017 Chalmers, M.K., and

Edwards, P.N. (2017)

“Producing 'one vast index': Google Book

Search as an algorithmic system”,

Big Data &

Society, 4(2). Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717716950.

DeRose et al. 1990 PLACEHOLDER

Gitelman 2013 Gitelman, L. (ed.) (2013) "Raw Data" Is an Oxymoron. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Goldfarb 1996 Goldfarb, C.F. (1996) “The roots of SGML — A personal recollection”, Technical Communication, 46(1).

Hiller 2015 Hiller, M. (2015)

“Signs o' the times: The software of philology and a philology of

software”,

Digital Culture and Society, 1(1), pp.

152–63. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.14361/dcs-2015-0110.

Jockers 2013 Jockers, M.L. (2013) Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History.

Urabana, Chicago, Springfield: UI Press.

Jones 2014 Jones, S.E. (2014) The

Emergence of the Digital Humanities. New York, London: Routledge.

Jones 2016 Jones, S.E. (2016) Roberto Busa, S.J., and the Emergence of Humanities Computing: The Priest and the

Punched Cards. New York, London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis

Group.

Kestemont et al. 2015 Kestemont, M., Moens, S.,

and Deploige, J. (2015)

“Collaborative authorship in the twelfth

century: A stylometric study of Hildegard of Bingen and Guibert of

Gembloux”,

Literary and Linguistic Computing,

30(2), pp. 199–224. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1093/LLC/FQT063.

Kestemont et al. 2017 Kestemont, M., de Pauw, G.,

van Nie, R., and Daelemans, W. (2017)

“Lemmatization for

variation-rich languages using deep learning”,

Digital

Scholarship in the Humanities, 32(4), pp. 797–815. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqw034.

Kirschenbaum 2008 Kirschenbaum, M. (2008)

Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination.

Cambridge (Massachusetts), London (England): The MIT Press.

Kittler 1993 Kittler, F. (1993) “Es gibt keine Software”, in Draculas

Vermächtmis, pp. 225–42. Leipzig: Reclam Verlag.

Lahti et al. 2020 Lahti, L., Mäkelä, E., and Tolonen,

M. (2020)

“Quantifying bias and uncertainty in historical data

collections with probabilistic programming”, in

Proceedings of the Workshop on Computational Humanities Research (CHR

2020), pp. 280-289. Amsterdam: CHR. Available at:

http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2723/short46.pdf.

Latour 1993 Latour, B. (1993) We

Have Never Been Modern. Translated by C. Porter. Cambridge, Massachusetts:

Harvard University Press.

Manovich 2013 Manovich, L. (2013) Software Takes Command. Vol. 5. International Texts in

Critical Media Aesthestics. New York, London, New Delhi etc.: Bloomsbury

Academic.

McPherson 2012 McPherson, T. (2012)

“Why are the digital humanities so white? Or thinking the histories

of race and computation”, in M.K. Gold (ed.)

Debates

in the Digital Humanities, pp. 139–60. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press. Available at:

http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/29.

Metz and Owen 2016 Metz, S., and Owen, K. (2016) 99 Bottles of OOP. Potato Canyon Software, LLC.

Morozov 2013 Morozov, E. (2013) To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism.

New York: PublicAffairs.

Nyhan and Flinn 2016 Nyhan, J., and Flinn, A. (2016)

Computation and the Humanities: Towards an Oral History of

Digital Humanities. Springer Series on Cultural Computing. Cham (CH):

Springer Open. Available at:

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319201696.

Piper 2015 Piper, A. (2015)

“Novel

devotions: Conversional reading, computational modeling, and the modern

novel”,

New Literary History, 46(1), pp.

63–98. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2015.0008.

Purdy and Walker 2010 Purdy, J.P., and Walker, J.R.

(2010) “Valuing digital scholarship: Exploring the changing

realities of intellectual work”, Profession,

pp. 177–95.

Rybicki et al. 2014 Rybicki, J., Hoover, D., and

Kestemont, M. (2014)

“Collaborative authorship: Conrad, Ford and

rolling delta”,

Literary and Linguistic

Computing, 29(3), pp. 422–31. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqu016.

Senseney 2016 Senseney, M. (2016)

“Pace of change: A preliminary YesWorkflow case study”,

Technical Report 201601–1. Urbana: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Available at:

https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/91046.

Underwood 2013 Underwood, T. (2013)

PLACEHOLDER

Underwood and Sellers 2014 Underwood, T.,

and Sellers, J. (2014)

“Page-level genre metadata for

English-language volumes in HathiTrust, 1700–1922”,

Figshare. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1279201.

Underwood and Sellers 2016a Underwood,

T., and Sellers, J. (2016)

“The longue durée of literary

prestige”,

Modern Language Quarterly, 77(3),

pp. 321–44. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1215/00267929-3570634.

Van Dalen-Oskam and Van Zundert 2007 Van

Dalen-Oskam, K., and Van Zundert, J.J. (2007)

“Delta for Middle

Dutch: Author and copyist distinction in *Walewein*”,

Literary and Linguistic Computing, 22(3), pp. 345–62. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqm012.

Van Zundert 2016 Van Zundert, J.J. (2016)

“Author, editor, engineer — Code & the rewriting of authorship in

scholarly editing”,

Interdisciplinary Science

Reviews, 40(4), pp. 349–75. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03080188.2016.1165453.

Vee 2013 Vee, A. (2013) “Understanding computer programming as a literacy”, Literacy in Composition Studies, 1(2), pp. 42–64.

Vee 2017 Vee, A. (2017) Coding

Literacy: How Computer Programming Is Changing Writing. Software Studies.

Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.