Abstract

Accurate dating of historical texts is essential for understanding cultural and

historical narratives. However, traditional methods, such as paleographic and

physical examination, can be subjective, costly, and potentially damaging to

manuscripts. This paper introduces a machine learning approach to predicting the

authorship dates of historical texts by using named entities — specifically,

person and place names — as temporal markers. Using a dataset from Trismegistos,

which includes metadata on the earliest and latest possible writing dates, we

apply regression models to estimate text origins. While linear models like Lasso

and Ridge Regression showed limited success, nonlinear models, including Random

Forest, XGBoost, and Neural Networks, performed significantly better, with

ensemble methods delivering the best results. The top-performing ensemble model

achieved a mean absolute error of 45.7 years, surpassing traditional techniques.

This study demonstrates the potential of named entities as temporal indicators

and the effectiveness of ensemble learning in capturing complex historical

patterns. Offering a scalable, non-destructive alternative to traditional

methods.

1. Introduction

Accurate dating of historical texts and manuscripts remains a critical challenge

for scholars, archivists, and curators, as it fundamentally shapes the

understanding of historical narratives, cultural developments, and the evolution

of ideas, yet traditional methods often fall short in providing precise

chronological placement for many documents. This paper discusses the development

and implementation of a machine learning based regression model designed to

predict the year of origin for historical texts. Traditional historical

manuscript dating (HMD) techniques, including paleographic and physical

examination, present significant limitations due to their reliance on actual

manuscript samples and their associated costs, time investment and potential for

damage, motivating the exploration and development of modern computer-based

alternatives [

Omayio et al. 2022]. While direct physical techniques, such as

radiocarbon dating [

Jull et al. 1995], provide a means to compute the production date

of historical manuscripts, they are destructive due to the use of a sample from

the manuscript itself and can be affected by contaminants, leading to

inaccuracies. In addition, methods such as radiocarbon dating provide the

production date of writing support or material, which may not necessarily

provide the authorship date of the content within the manuscript. Indirect

physical techniques, such as spectroscopic methods, suffer from the same

drawbacks. However, they offer the advantage of being non-destructive, but can

still be influenced by modern pigments, leading to misleading conclusions

regarding the manuscript’s age. The existence of such pigments can cast doubt on

their authenticity and age, suggesting possible later modifications,

restorations, or contamination [

Castro et al. 2004] [

Omayio et al. 2022]. Similarly, while

paleographic analysis — which relies on the expertise of trained paleographers

to assess handwriting styles and manuscript features — has historically been

used for dating historical texts, this approach is often subjective, leading to

inconsistencies and disagreements in dating conclusions among experts, therefore

posing a challenge in the accuracy of historical manuscripts [

Omayio et al. 2022].

Analyzing writing style is another method of dating ancient texts [

Van Schaik 2013]. However, this method can also introduce inconsistencies and biases,

limiting the reliability of findings. A machine learning approach to

automatically analyze and date historic manuscripts can offer a more objective

and efficient solution to this problem.

In this project, machine learning techniques were used to predict the year that a

historical text was written, using named entities (person and place names) as

key features. This approach is based on the premise that the presence of

specific person and place names in a text can serve as temporal markers, helping

to estimate the period in which the text was written.

A machine learning approach is particularly useful in the context of dating

historical texts due to its ability to process large amounts of data

efficiently, identify complex patterns, and provide objective, consistent

results. Unlike traditional methods, machine learning can adapt to various

languages and time periods and continuously improve as more data becomes

available. This approach also offers a non-destructive alternative to physical

dating methods, preserving valuable historical artifacts. By leveraging these

advantages, machine learning techniques can significantly enhance the ability to

date historical texts accurately and efficiently, contributing to a deeper

understanding of historical narratives and cultural developments.

The dataset for this study consists of a one-hot encoded matrix of person and

place names extracted from historical texts, alongside metadata specifying the

earliest (y1) and latest (y2)

possible writing dates. Since many records contain exact years (y1 = y2), a regression model to

predict a specific year of authorship was best fit. However, for texts with

uncertain dates (y1 ̸= y2),

additional strategies were considered to refine the predictions. The objectives

included exploring patterns in the data, handling date uncertainty, building a

predictive model, and improving its accuracy through feature selection and

ensemble techniques. To evaluate model performance, the mean absolute error was

used. This study makes significant contributions to the fields of historical

text dating and computational humanities. By leveraging named entity-based

features, the research demonstrates their effectiveness as strong temporal

indicators for predicting authorship dates. Furthermore, it highlights the power

of ensemble learning in improving prediction accuracy. Additionally, the

research provides valuable insights into the challenges associated with dating

texts from specific time periods.

2. Related Work

Recent advancements in computational techniques have significantly enhanced the

dating of historical texts and manuscripts. [

Moscato et al. 2022] utilized a memetic

algorithm-based Continued Fraction Regression (CFR) to date 181 Shakespeare-era

plays (from 1585-1610), achieving a Mean Squared Error (MSE) of 21.25 by

analyzing word frequency patterns, demonstrating the potential of

regression-based methods for temporal prediction. Similarly, [

Pavlopoulos et al. 2024]

applied text regression to Greek papyri, achieving a mean absolute error of 54

years using extremely randomized trees, emphasizing textual features over

subjective paleographical methods. [

Hellwig 2019] employed supervised learning

with linguistic features to date Classical Sanskrit texts, successfully

classifying over 80% of the Bh¯ıs.maparvan’s adhy¯ayas, while [

Yu and Huangfu 2019]

leveraged bidirectional LSTM networks for ancient Chinese texts, achieving 95%

accuracy without manual feature extraction.

Handwritten document recognition has also progressed, with [

Ullah and Jamjoom 2022]

achieving 96.78% accuracy in recognizing Arabic script using Convolutional

Neural Networks (CNNs), addressing challenges posed by cursive forms and style

variations. [

Wahlberg et al. 2016] applied deep convolutional neural networks to

premodern manuscripts, achieving a median absolute error of ±11.1 years,

outperforming handcrafted feature methods (MSE 810-1389) with transfer learning

and Sparse Gaussian Process regression. [

He et al. 2014] introduced the Medieval

Paleographic Scale (MPS) project, combining global and local regression for a

mean absolute error of 35.4 years, while their 2016 study proposed a clustering

algorithm (MLSOM) with a novel H2OS descriptor, yielding a mean absolute error

of 15.9 years. [

Hamid et al. 2018] fused textural features (Gabor, U-LBP, LBP) for a

mean absolute error of 20.13 on the Medieval Paleographic Scale dataset, and

[

Koopmans et al. 2024] explored data augmentation with support vector machines,

improving accuracy by 4.5% despite selective feature effectiveness.

[

Kumar et al. 2011] applied a supervised language modeling approach to date fictional

texts by capturing implicit temporal cues through Kullback-Leibler Divergence,

achieving a median error of 23 years on Gutenberg short stories (1798–2008),

thus refining document dating in narrative corpora. Similarly, [

Han et al. 2023]

introduced the Time-Aware Language Model (TALM), which incorporates temporal

adaptation to align word representations across historical periods. Evaluated on

Chinese and English corpora, TimeAware Language Model achieved an F1 score of

84.99% on the Twenty-Four Histories Corpus, surpassing state-of-the-art models

in diachronic text analysis. Grapheme-based handwriting analysis using

Self-Organizing Time Maps (SOTM) was employed by [

Dhali et al. 2020] to cluster

historical scripts, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls, into temporal categories,

achieving a mean absolute error of 23.4 years. While outperforming traditional

texture-based methods, the approach is constrained by its reliance on

categorical classification and handwriting features, limiting its scalability

across languages and document types.

[

Assael et al. 2025] use a tool, Aeneas, a generative neural network for

contextualizing ancient texts. Aeneas has a much broader scope than our project

as its goals are to contextualize ancient texts and artifacts, going as far as

performing restoration. As of the date published in the article, Aeneas

currently focuses on Latin data.

3. Dataset

3.1. Origin of the dataset

The website Trismegistos, accessible at

https://www.trismegistos.org, functions as a digital resource for

investigating ancient civilizations across a broad geographic expanse,

encompassing regions from Scandinavia to Ethiopia and from the Canary

Islands to the Indus Valley, during the era from 800 BCE to 800 CE[

Depauw 2018]. Originating from several research endeavors at KU Leuven, the

platform initially concentrated on Egyptian papyri and other textual

artifacts, with a particular focus on the individuals and locations they

reference. The database has developed gradually, beginning with manual data

input and periodic updates through partnerships with affiliated projects.

More recently, it has integrated specially designed, rule-based Named Entity

Recognition (NER) models to partially automate the extraction of references

to people and places from comprehensive text repositories, such as those

found on papyri.info [

Broux and Depauw 2015] [

Depauw and Van Beek 2009]. Each record in the dataset

is meticulously structured and annotated, featuring extensive metadata that

includes details on the text’s origin, chronological placement, language,

genre, physical properties, and thematic content. This detailed metadata

empowers scholars to examine and interpret the texts within their respective

historical, linguistic, cultural, and geographic frameworks. Academics and

specialists from a variety of disciplines — ranging from archaeology and

history to philology, linguistics, and digital humanities — utilize the

Trismegistos dataset for diverse research goals. The platform serves as a

crucial instrument for exploring ancient societies, their economic

frameworks, religious practices, languages, and cross-cultural dynamics,

thereby offering a deeper comprehension of the multifaceted nature of life

in the ancient world.

3.2. Structure of the dataset

The dataset obtained from Trismegistos comprises a comprehensive collection

of features that describe historical texts. It was processed to a one-hot

encoded manner, i.e., categorical data present in the dataset was

represented by binary values, with “1” indicating the presence of a feature

and “0” indicating its absence. The dataset includes a total of 11,599

unique person names and 4,784 place names, each formatted with a specific

identifier. Each text entry is uniquely identified by a text ID, which

serves as a reference point for the associated features.

In addition to the features, the dataset contains corresponding labels that

provide information regarding the approximate date range of each text’s

creation. Key variables within the labels represent this date range: one

variable serves as the approximate start date (y1),

while another serves as the approximate end date (y2). When y1 equals y2,

it indicates the exact year of creation of the ancient text. The one-hot

encoded dataset consists of 30,324 rows (texts) and 16,383 columns

(features).

The labels (year of writing) included 29,250 rows, containing the dependent

variables (y1 and y2) that the

models aim to predict. These labels provide the reference values against

which the model’s predictions are evaluated during both training and testing

phases. This dataset is structured to facilitate effective training and

evaluation of machine learning models for historical text dating.

Proper alignment between the datasets was a critical preprocessing step. Each

text sample was associated with a unique identifier (text ID), which was

used to match corresponding entries across both datasets. As some entries in

the feature set did not have matching labels, and vice versa, an inner join

was performed using this identifier to retain only the samples present in

both datasets. Following this alignment, the resulting dataset comprised

8,565 entries, each containing both feature representations and their

corresponding labels.

4. Methodology

4.1. Preprocessing and Data Exploration

For most models, additional scaling was unnecessary. However, for the neural

network, StandardScaler was applied to transform each feature to have zero

mean and unit variance. This step was important for mitigating issues such

as vanishing or exploding gradients and ensuring compatibility with normal

weight initialization. The target variable y was normalized to the range

using MinMaxScaler, aligning with the linear output activation function and

mean absolute error loss function employed during training.

Since the features were highly sparse, low-variance features were filtered

using a threshold of 0.001. This process significantly reduced the feature

space from 16,383 to 1,345 columns.

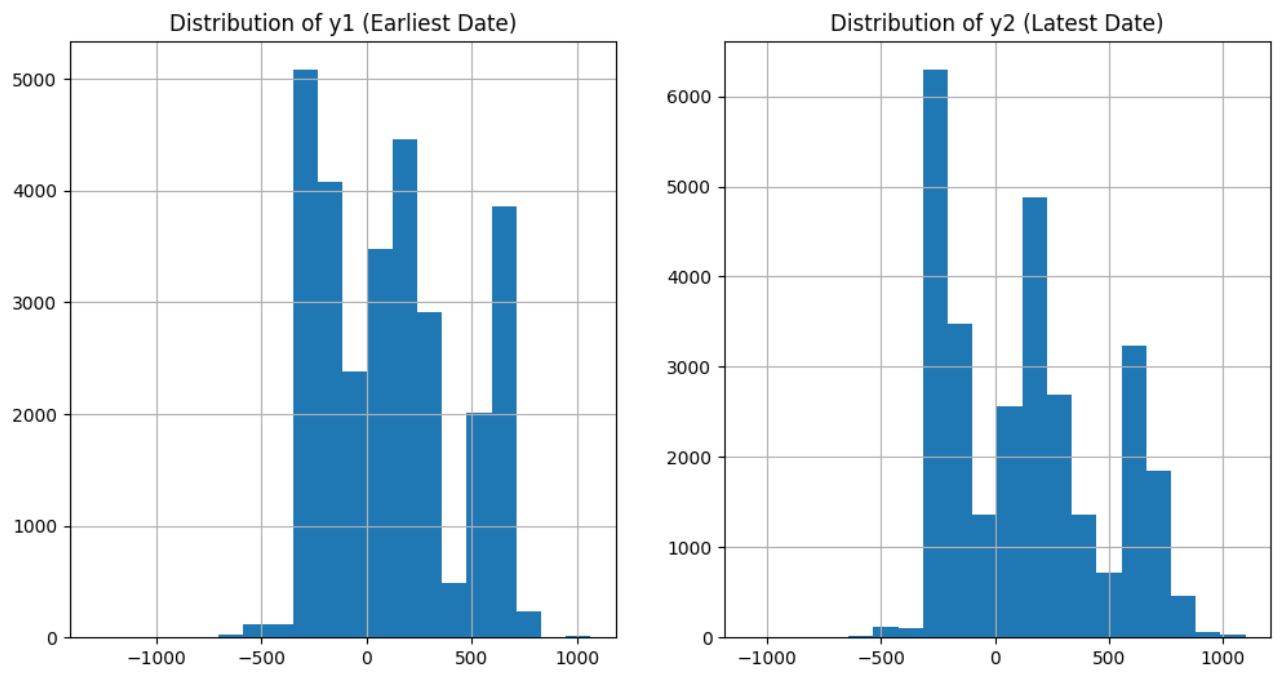

The mean values for the earliest y1 and latest y2 recorded dates were approximately -119 and 146,

respectively (see Figure 1 for the distribution of earliest and latest

dates).

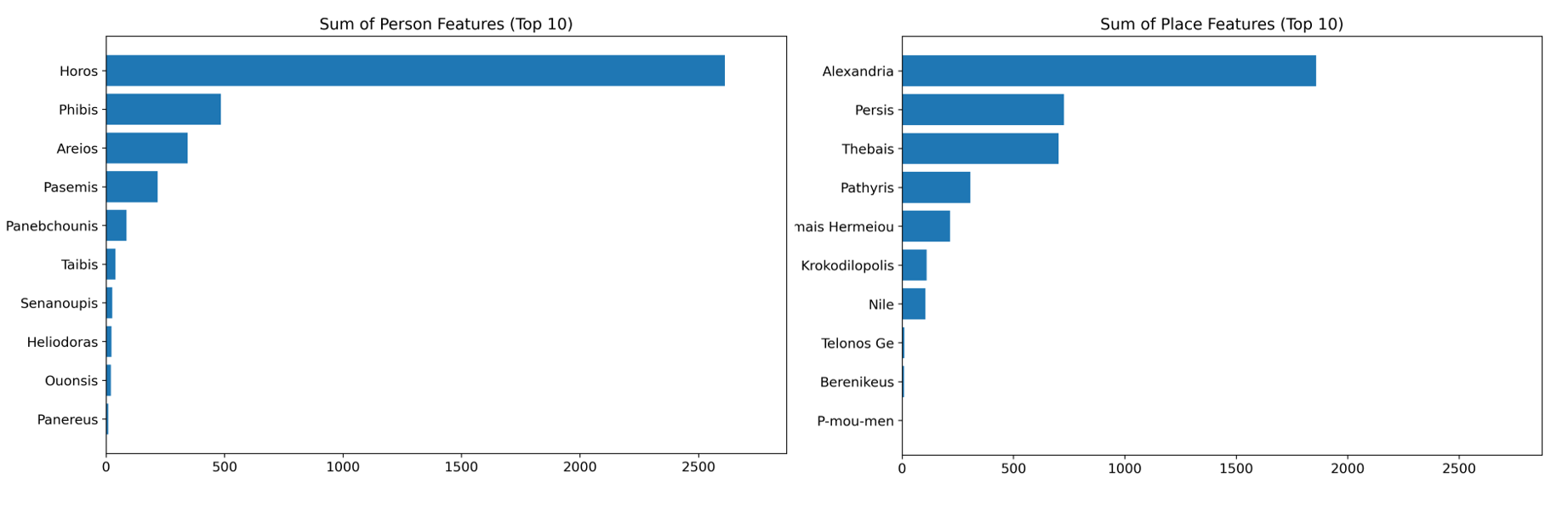

The top 10 most frequently occurring features related to persons and places

across the dataset were visualized by generating bar graphs (refer to Figure

2). These visualizations provided insight into key feature distributions and

their potential influence on model predictions.

To determine the most appropriate modeling approach, the distribution of

exact (y1 = y2) and non-exact

(y1 ̸= y2) year matches in

both raw and filtered datasets were assessed. In the raw dataset, it was

found 16,698 rows where y1 = y2 and 12,550 rows where y1 ̸= y2. After filtering, the dataset contained 5,239 rows

where y1 = y2 and 3,326 rows

where y1 ̸= y2. This higher

proportion of exact years in both the raw and filtered datasets suggested

that regression would be more suitable for the task. It was believed that

regression was the better approach because predicting an exact year (a

continuous variable) aligns with the strengths of regression, and the

majority of the ground truths were a single continuous year rather than a

range of years.

Since regression was chosen, a target column that handles both cases: when

y1 equals y2 (a single

year) and when y1 does not equal y2 (a range of years) was created. The target variable, y target,

was set to y1 in cases where the two values were

equal. When they differed, the y target was assigned the midpoint of y1 and y2, as the midpoint

provides a reasonable estimate for a range when an exact year is

unavailable. This new target column replaced y1 and

y2 as the ground truth label. All other ground

truth labels were dropped, as they were deemed unnecessary for predicting

the year a text was written. However, it could be worthwhile to explore

using these additional labels as features in the dataset to assess whether

they improve model performance.

4.2. Feature Engineering

4.2.1. Feature Importance Evaluation

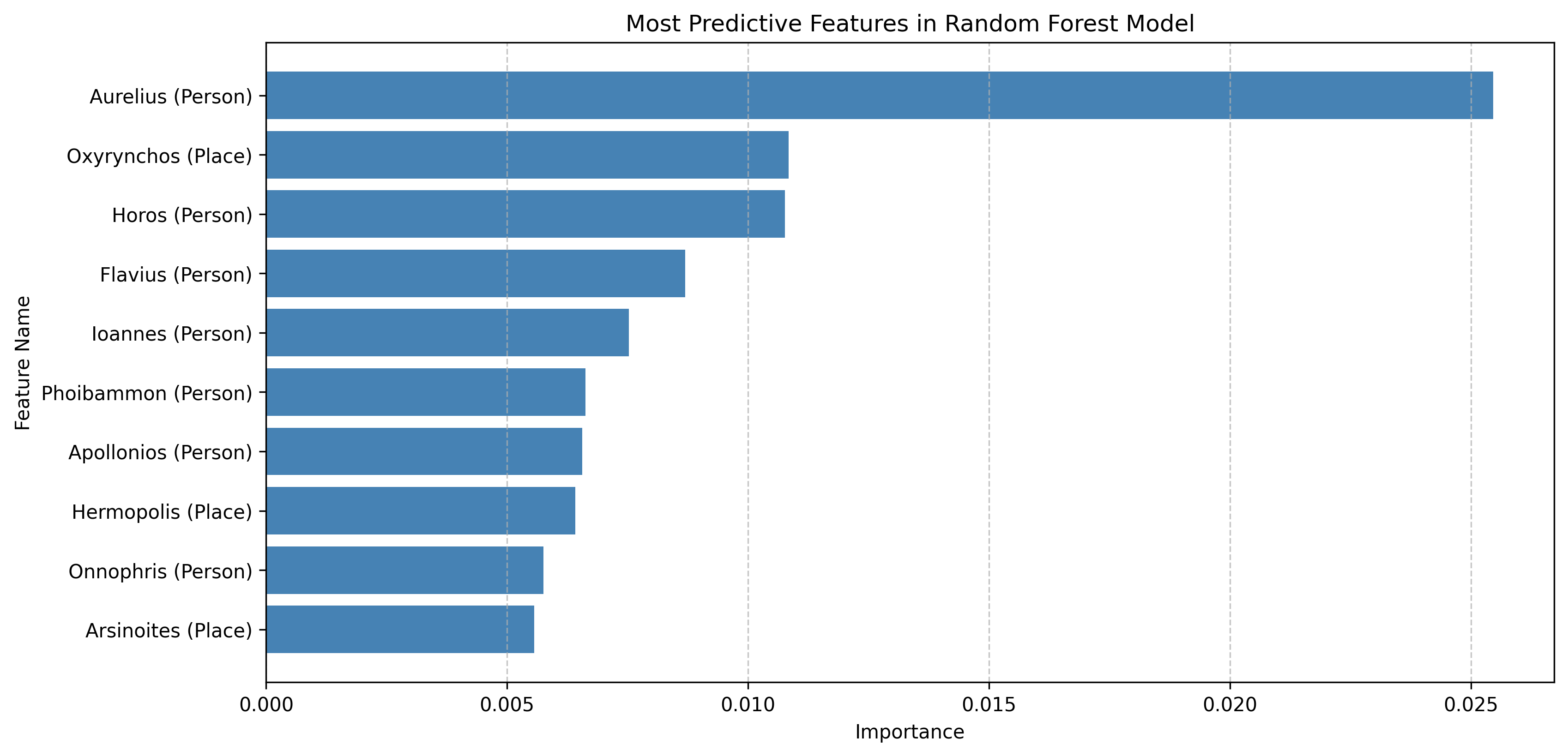

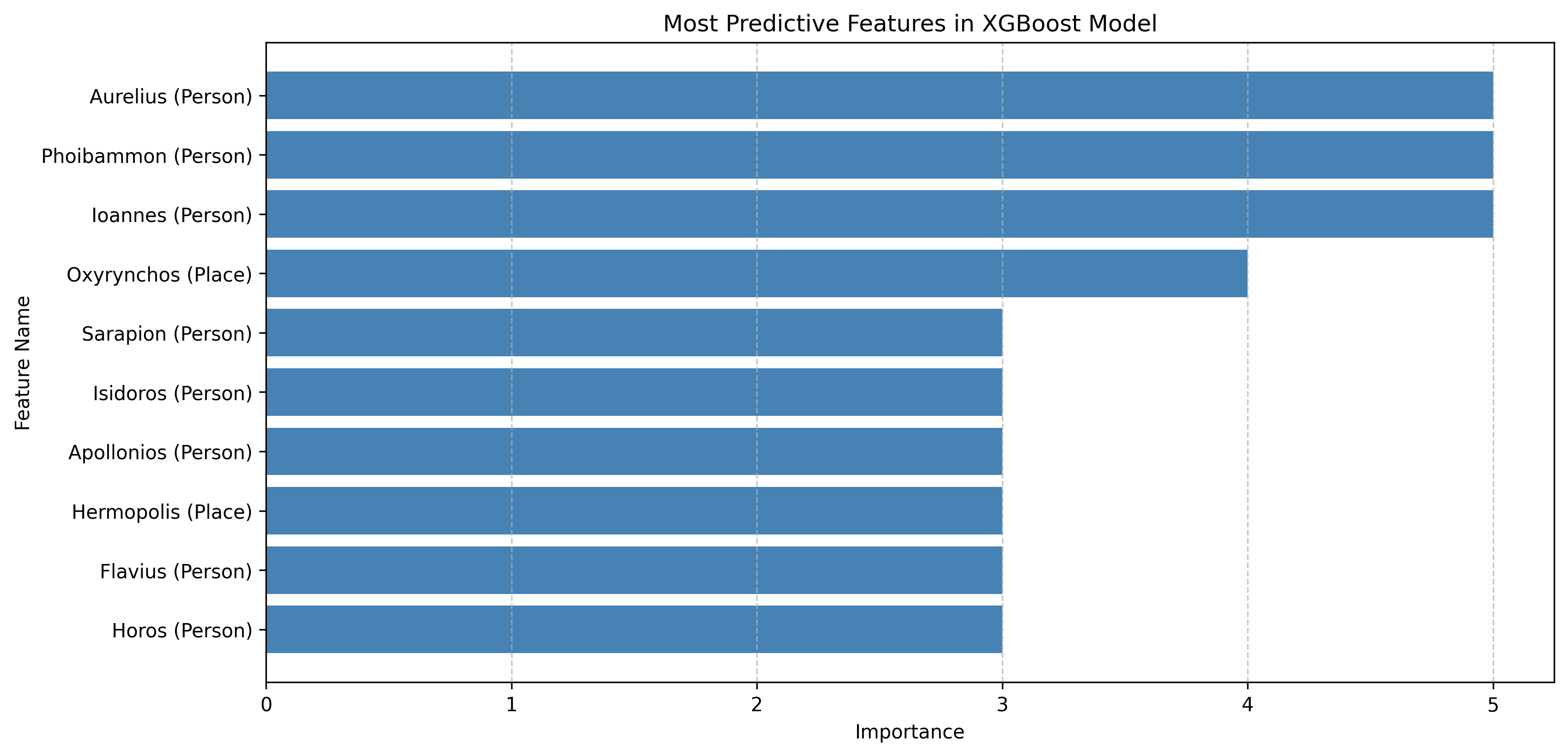

In order to understand the most predictive features, the most predictive

Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) transformed features were calculated.

Then each singular value decomposition transformed feature was mapped to

its original weighted components. Next, the weights were aggregated

across all singular value decomposition components to estimate the

contribution of each original feature (name/place). The top-ranked

features were then selected based on highest weights. The plots below

illustrate the top 10 most important features for both the Random Forest

and XGBoost models (Figures 3 and 4).

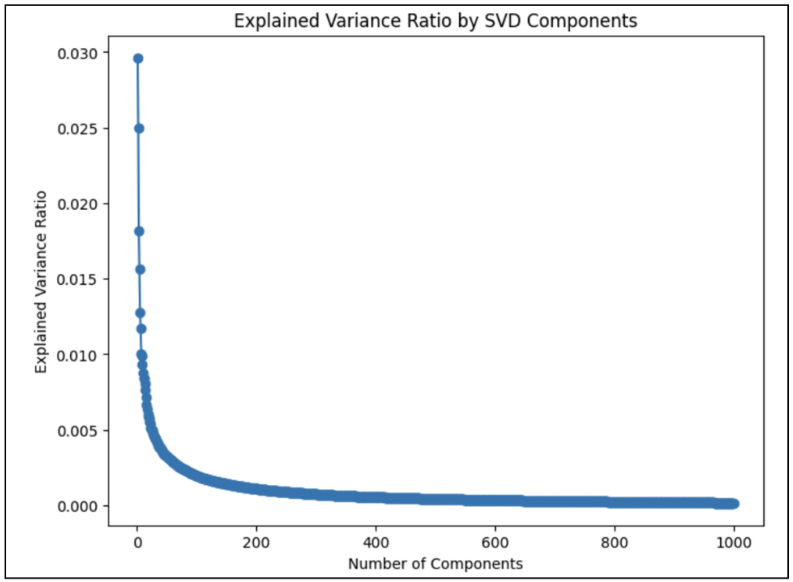

4.2.2. Dimensionality Reduction and Feature Transformation

To address the challenges posed by high-dimensional datasets, singular

value decomposition was employed as the method for dimensionality

reduction. Singular value decom position is particularly effective in

reducing the number of features in sparse matrices, which characterize

the dataset. Through empirical testing, 1,000 principal components were

selected, allowing for the retention of 95% of the variance in the data

despite a reduction in feature count by over 15,000. This choice

demonstrated strong performance, as evidenced by the explained variance

ratio.

To better understand the impact of dimensionality reduction through

singular value decomposition, an analysis was conducted on the plot

depicting the explained variance ratio across the components. This plot

illustrates the extent to which the variation in the original data is

captured by a specific number of singular value decomposition components

(refer to Figure 5).

When exploring the number of components significantly exceeding 1,000, it

was observed that variance retention often surpassed 0.9999, leading to

suboptimal model performance due to overfitting.

To further refine the dataset, low-variance feature removal was

implemented, discarding features with minimal variation across the

dataset. The VarianceThreshold was applied to eliminate features with a

variance below 0.001, resulting in a reduction of the original 16,383

features to 1,345. This process enhanced computational efficiency while

preserving the model’s ability to capture meaningful patterns.

Through the combination of dimensionality reduction with singular value

decomposition and low-variance feature removal, a more compact and

informative dataset was successfully created. This transformation

streamlined the original one-hot encoded features while maintaining key

patterns, thereby improving the efficiency and effectiveness of machine

learning models.

4.3. Model Development

4.3.1. Data Preparation and Scaling

To prepare the dataset for model training and evaluation, it was split

into training and testing subsets. The features (denoted as (X))

included all input variables, while the labels (denoted as (y))

corresponded to the target years or year ranges for prediction. 80% of

the data was allocated for training, while the remaining 20% was

designated for testing, and a random seed of 42 was employed to ensure

reproducibility during the splitting process.

The purpose of this split was to evaluate the model’s generalization

capabilities on unseen data. The training set was utilized to fit the

model, while the test set provided an unbiased estimate of its

performance.

For most models, scaling was not required due to the dataset being

one-hot encoded and subsequently reduced through Variance Thresholding

and singular value decomposition. Variance Thresholding eliminated

low-variance features without altering their scale, and singular value

decomposition produced principal components that were already normalized

during the decomposition process. As a result, the features were

well-suited for most algorithms without additional preprocessing.

The neural network required additional scaling to ensure efficient and

stable training. Given that neural networks are sensitive to feature

magnitudes due to their reliance on gradient descent optimization,

Feature Scaling and Target Scaling methods were applied.

StandardScaler was applied to (X), transforming each feature to have zero

mean and unit variance. This approach mitigated issues such as vanishing

or exploding gradients and ensured compatibility with the network’s He

Normal weight initialization. In addition, MinMaxScaler was applied to

(y), normalizing values to the range [0, 1]. This normalization aligned

the target variable with the linear output activation function and the

mean absolute error loss function employed during training.

Standardizing the input features improved gradient-based optimization,

resulting in faster convergence and more stable weight updates.

Moreover, normalizing the target variable ensured that predictions were

appropriately scaled to match the training objectives.

After

scaling, the final datasets were (X train scaled) and (y train scaled),

which was utilized for model training, and (X test scaled) and (y test

scaled), which was used for evaluating model performance on unseen data.

Scaling transformations were implemented as a pipeline to ensure

consistent preprocessing for both training and testing datasets,

enhancing reproducibility and reliability.

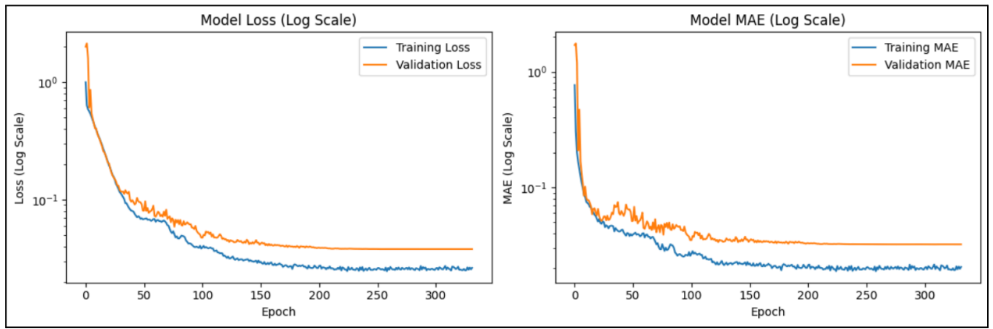

Additionally, the EarlyStopping callback was utilized during training to

terminate the process early if the validation loss ceased to improve.

The ReduceLROnPlateau callback was also employed to decrease the

learning rate when the model’s performance plateaued. These techniques

prevented overfitting, maintaining a validation mean absolute error

close to the training mean absolute error (e.g., 49.785 vs. 48).

4.3.2. Model Implementation Ridge

4.3.2.1. Regression

A Ridge regression model was employed with cross-validation using 5

folds. Ridge regression incorporates an L2 regularization term into

the linear regression model, penalizing large coefficient values to

help prevent overfitting. The strength of the regularization is

controlled by the alpha parameter when instantiating the RidgeCV

class. The 5-fold cross-validation process involved partitioning the

training data into 5 parts, training the model on 4 parts, and

validating on the remaining part, repeating this process across all

folds.

The mean absolute error, which measures the average absolute

difference between predicted values and ground truths, was computed.

The best Ridge model yielded a training mean absolute error of

109.62 and a testing mean absolute error of 124.12, representing

some of the lowest scores among all models evaluated. The relatively

poor performance of Ridge and Lasso regression compared to other

models suggested that the data exhibited nonlinear

characteristics.

4.3.2.2. Lasso Regression

A Lasso linear regression model was also utilized with 5-fold

cross-validation. Lasso regression incorporates an L1 regularization

term, allowing some coefficients to be shrunk to zero, effectively

reducing the feature set. Despite tuning the alpha hyperparameter,

Lasso emerged as one of the poorer performing models, achieving a

training mean absolute error of 113.21 and a testing mean absolute

error of 125.16 with the optimal alpha value set at 0.109.

4.3.2.3. Random Forest

A Random Forest model was employed for regression tasks, constructing

an ensemble of 100 decision trees. This ensemble learning algorithm

combines multiple weak decision trees to enhance prediction accuracy

and reduce overfitting. Bootstrap sampling was utilized to randomly

select samples with replacement from the training data, creating

several datasets for training individual trees. Each decision tree

predicted a value, and the final prediction was derived from the

average of all tree predictions in the forest.

The initial Random Forest model produced significantly better results

than the linear models, achieving a training mean absolute error of

30.7 and a testing mean absolute error of 78.6 after 8 minutes and

15 seconds of execution. The Random Forest Regressor emerged as one

of the highest-performing models in this study, significantly

outperforming linear models such as Lasso and Ridge regression. To

further enhance its performance, hyperparameter optimization was

conducted using GridSearch with cross-validation, systematically

exploring a range of hyperparameter combinations to identify optimal

settings for the model.

The parameters tuned included:

- max depth: The maximum depth of each decision tree.

- min samples split: The minimum number of samples required to

split a node.

- n estimators: The number of decision trees in the forest.

5-fold cross-validation was employed to ensure the robustness

and generalizability of the model during the tuning

process.

4.3.2.4. Optimal Hyperparameters

Following the GridSearch process, the following hyperparameters were

identified as optimal:

- max depth: 20

- min samples split: 5

- n estimators: 300

4.3.2.5. Model Performance

With the optimized hyperparameters, the Random Forest Regressor was

retrained and evaluated on both the training and testing datasets,

yielding:

- Training Mean Absolute Error: 31.35

- Testing Mean Absolute Error: 77.80

The improvements achieved through hyperparameter tuning underscored

the model’s ability to capture complex, nonlinear patterns in the

dataset. Although the Random Forest Regressor delivered strong

results, additional experimentation with other advanced models was

conducted to explore further enhancements in predictive

performance.

4.3.2.6. Gradient Boosting

The gradient boosting model, specifically XGBoost, was employed as an

efficient and accurate framework for machine learning. Various

parameters were manually adjusted to improve model performance,

reducing the mean absolute error from 81 to 71.

Boosting is an ensemble learning technique that sequentially combines

weak learners (such as shallow decision trees) to form a strong

learner. Each new tree is trained to correct the errors made by the

previous trees. The XGBoost framework incorporates regularization to

prevent overfitting, is optimized for speed and low memory usage,

and supports sparse data.

The XGBoost model was notably efficient, taking only 20 seconds to

run, and achieved a mean absolute error of 71.2 with an R-squared

score of 0.84. This R-squared value indicates that 84% of the

variation in the target variable was captured by the model,

demonstrating the predictive power of the selected features.

4.3.2.7. Neural Network

A deep neural network (DNN) was designed using TensorFlow for

regression tasks. The architecture consisted of an input layer that

accepted input data with a specified dimension, followed by four

hidden layers with progressively decreasing neuron counts to refine

feature extraction. The first hidden layer contained 512 neurons

with ReLU activation, He initialization, L2 regularization (1e-4),

batch normalization, and a dropout rate of 0.36. The second layer

had 256 neurons with similar settings but a slightly lower dropout

rate of 0.3. The third layer had 128 neurons and followed the same

configuration as the second, while the fourth layer contained 64

neurons with reduced L2 regularization (1e-5). The final output

layer consisted of a single neuron with a linear activation

function, making it suitable for regression tasks.

To optimize performance and prevent overfitting, batch normalization

was incorporated after each hidden layer, facilitating faster

convergence and reducing sensitivity to initialization. The Adam

optimizer with gradient clipping was utilized to enhance stability

during training. The model was trained with a learning rate of 1e-2,

a batch size of 512, and for a total of 500 epochs. Early stopping

was applied, monitoring validation loss with a patience of 50

epochs, while learning rate reduction halved the rate after 8 epochs

without improvement, with a minimum learning rate of 5e-7. Key

hyperparameters, including learning rate, batch size, and early

stopping patience, were fine-tuned based on validation

performance.

To further optimize the model, several techniques were

implemented:

- Dropout Regularization: Prevents over-reliance on specific

neurons by randomly dropping units during training.

- Learning Rate Scheduling: The ReduceLROnPlateau callback was

implemented to halve the learning rate after 8 epochs without

improvement.

- Early Stopping: Training was halted when validation loss

plateaued, ensuring computational efficiency.

- 10-Fold Cross-Validation: The model was evaluated across 10

folds to minimize bias and variance.

4.3.2.8. Ensemble Models

Finally, individual model outputs were combined using weighted

ensemble techniques, which included:

- Weighted Neural Network Ensemble: The neural network ensemble

was constructed by leveraging the models generated during

10-fold cross-validation. Each of the 10 neural network models

which were trained on a unique combination of training and

validation splits, was preserved. These models were then

combined into a single ensemble by computing a weighted average

of their predictions. The weights were determined based on each

model’s validation performance, assigning greater influence to

models with lower mean absolute error. By aggregating models

trained on distinct training-validation splits, the ensemble

incorporated diverse learned patterns, which reduced model bias

and variance, leading to stronger generalization. As a result,

the neural network ensemble achieved a lower mean absolute error

than any individual model, highlighting the benefit of

aggregating multiple individually trained models into a stronger

predictive model.

- Super Ensemble: Integrated outputs from the neural network,

Random Forest, XGBoost, and LightGBM models. Although this

approach did not achieve the lowest mean absolute error, it

demonstrated the potential for blending diverse algorithms to

capture varied aspects of the data.

The super ensemble served as an experimental approach to validate the

robustness of the combined methodologies, balancing trade-offs

between mean absolute error and R-squared scores.

4.3.3. Hyperparameter Tuning

Hyperparameter tuning was performed for different models based on their

respective characteristics using methods such as LassoCV, RidgeCV and

GridSearchCV for the RandomForest model. LassoCV and RidgeCV are

specialized implementations of the Lasso and Ridge regression in

scikit-learn that automatically optimize the alpha parameter through

cross validation. Similarly, GridSearchCV enables an exhaustive cross

validation search over a predefined set of hyperparameter values to

identify the optimal configuration.

For the Lasso and Ridge regression models, the alpha hyperparameter was

tuned, as it determines the strength of regularization applied to the

model’s coefficients. Optimizing alpha is crucial to balancing bias and

variance, thereby preventing both underfitting and overfitting.

Hard-coded alpha values were specified for the RidgeCV model to evaluate

its performance across different levels of penalization.

For the Random Forest model, hyperparameters were optimized, including n

estimators (number of trees), max depth (maximum depth of each tree), and min

samples split (minimum number of trees required to split a node). Using

GridSearchCV, predefined values for these hyperparameters were explored

to determine the optimal combination. Once the best hyperparameters were

identified, the RandomForestRegressor was trained with the optimized

settings, leading to expected performance improvements.

Further exploration of other models was conducted to assess potential

improvements in predictive performance. The Gradient Boosting model

underwent manual hyperparameter tuning, where parameters were adjusted

iteratively based on the mean absolute error of each model iteration.

The tuned parameters included colsample_bytree, learning_rate,

max_depth, alpha, and n_estimators, to determine the configuration that

minimized the mean absolute error. If a change in a hyperparameter value

resulted in a lower mean absolute error, further adjustments were made

in the same direction until the improvement plateaued. Once a parameter

reached an optimal value, the next hyperparameter was tuned following

the same approach. This iterative process was repeated until no further

reductions in mean absolute error were observed, ensuring that the model

achieved the best possible performance with the tuning constraints.

Initial results from the Support Vector Machine (SVM) model indicated

poor performance, with a mean absolute error of 226.18. However,

visualizing predictions against actual values revealed that the

predictions were clustered around 100, suggesting the need for

hyperparameter adjustment. Increasing the C hyperparameter to 956.1

improved the support vector machine’s mean absolute error to 94.5.

For the neural network model, key hyperparameters, including learning

rate, batch size, and number of epochs, were fine-tuned to enhance

predictive accuracy. A dynamic learning rate was implemented using the

ReduceLROnPlateau callback, which halved the learning rate, whenever

validation loss plateaued for 8 epochs. A batch size of 512 was selected

to balance training speed and accuracy, as smaller batch sizes improved

accuracy but extended training time, whereas larger batch sizes reduced

accuracy while accelerating training. Additionally, early stopping was

employed to prevent overfitting and unnecessary training.

Following these optimizations, the neural network model achieved an

average mean absolute error of 49.785 with a standard deviation of 3.87,

demonstrating significant improvement over the initial configurations.

This tuning process emphasized the importance of hyperparameter

optimization in refining model performance and highlighted the value of

cross-validation in ensuring robust and reliable results.

4.4 Evaluation

To prepare the dataset for model training and evaluation, it was split into

training and testing subsets. 80% of the data was allocated for training and

20% for testing, using a random seed of 42 to maintain reproducibility. The

feature matrix x comprised all input variables, while the target variable y

represented the predicted year or year ranges.

4.4.1. Cross-Validation

Cross-validation was employed to enhance the robustness of model

performance and mitigate the risk of overfitting. For Lasso linear

regression and Ridge regression, a 5-fold cross validation approach was

utilized. In the case of the Random Forest regressor, GridSearch

cross-validation was implemented, as discussed in Section 4.3.2, “Model

Implementation.”

For the neural network model, to ensure robust performance and prevent

overfitting, 10-fold cross-validation was implemented. This method

allows for the assessment of model robustness.

10-fold cross-validation was performed for the NN model with k set to 10,

resulting in the dataset being divided into 10 equal subsets. For each

fold, the model was trained on 9 of the subsets and validated on the

remaining one, ensuring that each subset was utilized for validation

exactly once.

The main steps in the cross-validation process are outlined as

follows:

| Model |

Mean Absolute Error |

| Lasso |

124.89 |

| Ridge |

123.8 |

| Random Forest |

77.8 |

| XGBoost |

71.4 |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) |

94.53 |

| Neural Network (NN) |

48 |

| RF + XG + LGBM + NN Ensemble |

47 |

| Weighted Neural Network Ensemble |

45.7 |

| Super Ensemble (Everything) |

46.9 |

Table 1.

Mean Absolute Error values for various models

- Data Splitting: The dataset was divided into 10 equal subsets.

Within each fold, feature scaling was performed using

StandardScaler, while target values were scaled using

MinMaxScaler.

- Model Training and Evaluation: For each fold, a new model was

instantiated using a neural network function create model (see

section 4.3.2), which defined a neural network architecture

comprising four dense layers, dropout layers, batch normalization,

and L2 regularization. The model was compiled with the Adam

optimizer, utilizing a learning rate of 1e-4, and trained on the

training subset. The validation subset was employed to evaluate the

model’s performance.

- Metrics: Model performance was assessed using the mean absolute

error metric, which served as a key evaluation criterion for the

regression task. The mean absolute error was computed for the

validation fold, and the average mean absolute error across all

folds was recorded.

Upon completion of the cross-validation process, the model exhibiting the

lowest average validation mean absolute error was selected for further

evaluation and testing, thereby ensuring that the model’s

hyperparameters were optimized for generalization.

4.4.2. Metrics

4.4.2.1. Mean Absolute Error

Mean Absolute Error is utilized to quantify the average magnitude of

errors in a set of predictions, without considering their direction.

The mean absolute error values for various models are presented in

Table 1.

The best overall model in terms of mean absolute error was the

Weighted Neural Network Ensemble (see section 6.1), which achieved

the lowest test mean absolute error of 45.7.

4.4.2.2. R-Squared (R²)

R-squared (R²) is a statistical measure that represents the

proportion of variance for a dependent variable that’s explained by

an independent variable or variables in a regression model. The R²

values for the models are summarized in Table 2.

| Model |

R² |

| Lasso |

0.62 |

| Ridge |

0.62 |

| Random Forest |

0.80 |

| XGBoost |

0.84 |

| Neural Network (NN) |

0.867 |

| RF + XG + LGBM + NN Ensemble |

0.9277 (Highest) |

| Weighted Neural Network Ensemble |

0.8878 |

| Super Ensemble (Everything) |

0.89 |

Table 2.

R² values for the models

The best overall model for R² was determined to be the RF + XG + LGBM

+ NN

Ensemble, exhibiting a high R² value closest to 1.

5. Results

Results from the analysis of historical text dating using various machine

learning models reveal that the relationships within the dataset are

predominantly nonlinear. The results clearly demonstrate the dataset’s

nonlinearity, as linear models like Lasso and Ridge Regression performed poorly,

with mean absolute error values exceeding 120 years, failing to capture complex

temporal patterns. In contrast, nonlinear models such as Random Forest, XGBoost,

and Neural Networks significantly reduced mean absolute error (as low as 45.7)

and achieved higher R² scores, confirming their ability to model intricate

relationships between named entities and historical time periods. The findings

highlight the importance of leveraging various nonlinear machine learning

techniques, such as ensemble models (Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM) and deep

learning (Neural Networks), capable of capturing complex interactions in the

data. This insight significantly influenced the model selection process,

highlighting the necessity of employing advanced methods capable of capturing

these complex interactions.

Linear models, such as Lasso and Ridge Regression, demonstrated inferior

performance compared to their nonlinear counterparts. The results reinforced the

notion that the underlying data exhibits intricate relationships that linear

models cannot effectively capture.

Ensemble methods like Random Forest and XGBoost, exhibited superior performance

in identifying complex patterns within the data.

The implementation of a neural network model further capitalized on the nonlinear

nature of the data. This approach allowed the exploration of deep learning

techniques, which are well-suited for capturing complex relationships. The

neural network achieved competitive performance, demonstrating its adaptability

to the dataset’s intricacies.

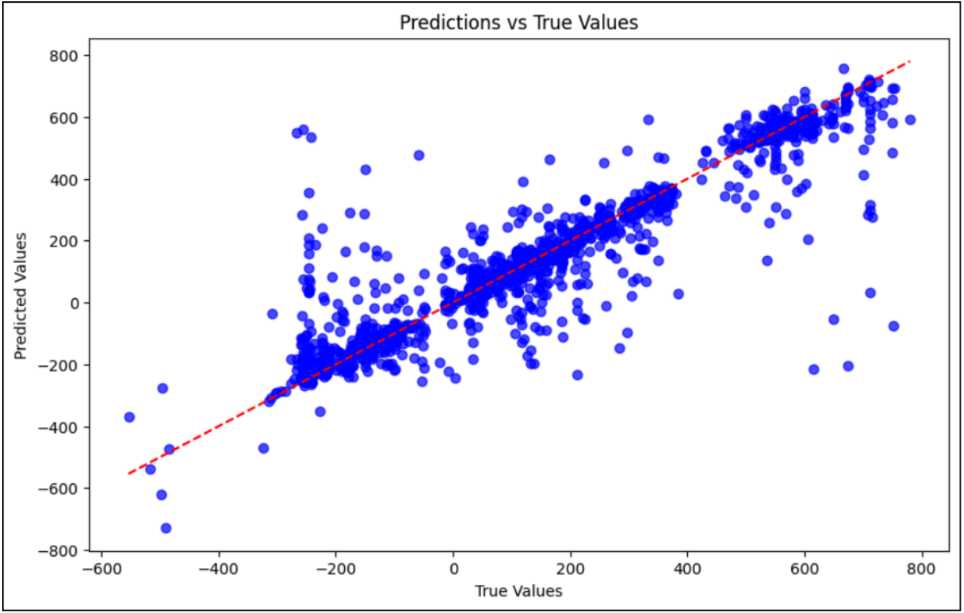

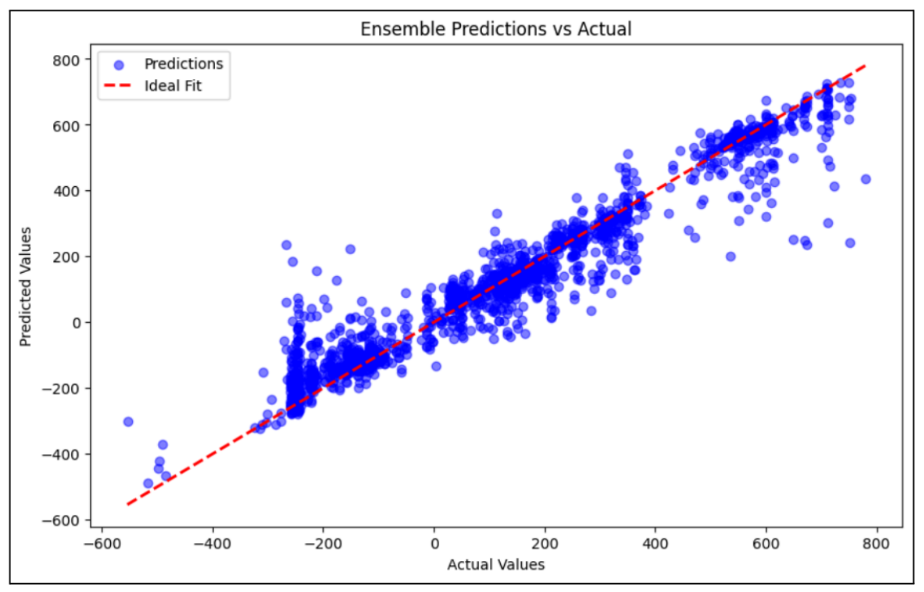

5.1. Visual Metrics

Scatter plots comparing predicted values to actual for each model (see

example Figures 6 and 7) revealed two distinct periods (200 BC and within

the range of 600-700 AD) where the predictions deviated from the actual

values. The scatter plots exhibit a high dispersion of points, particularly

in earlier historical points, which suggests unique challenges, such as

limited training data or ambiguous named entities in these periods. Further

refinement of the feature set or the inclusion of additional historical

context may be necessary to enhance predictions for these challenging

periods.

Figure 6:

5.2. Selected Examples

Here we present a selected set of examples to demonstrate the usage of this

method. The table contains three of the best predictions (lowest error) and

three of the worst predictions (highest error), along with the most

influential features that led to the prediction (the positive values next to

the feature indicate that there is a positive association between the

existence of that feature and the prediction. The negative value indicates

that there is a negative association between the existence of that feature

and the prediction.

| Case |

Actual |

Predicted |

Abs Error |

Influential Features |

| Best #1 |

248.0 |

248.0 |

0.0 |

Alexandros (+0.5), Lykophron (0.4), Oaphres (-0.4), Ammonios (+0.3)

|

| Best #2 |

120.0 |

120.1 |

0.1 |

Herakleides (+0.4), Aurelia (-0.3), Arsinoe (-0.2)

|

| Best #3 |

15.0 |

15.1 |

0.1 |

Apollonios (+0.5), Gorgias (-0.3), Kallias (-0.3)

|

| Worst #1 |

-256.0 |

184.2 |

440.2 |

Demetrios (+0.6), Isidoros (-0.4), Horion (-0.4), Karanis (-0.3)

|

| Worst #2 |

-120.0 |

300.4 |

420.4 |

Philoxenos (+0.5), Tryphon (-0.4), Theon (-0.3)

|

| Worst #3 |

-80.0 |

310.2 |

390.2 |

Sarapis (+0.5), Dionysia (-0.3), Paniskos (-0.3)

|

Table 3.

Top 3 best and worst model predictions with influential

features.

Figure 8 shows the neural network’s training and validation loss (left) and

mean absolute error (right) over epochs on a logarithmic scale. Model loss

stabilized within the 150-200 epoch range.

6. Discussion

This study showcases machine learning, especially ensemble models, for dating

historical texts, offering a scalable approach for computational humanities.

6.1. Performance of Different Models

The evaluation of multiple models revealed that linear models such as Lasso

and Ridge Regression performed poorly, with high mean absolute error values

exceeding 120 years. These models assume a linear relationship between

features and the target variable, which does not align with the inherent

complexities of historical text data.

In contrast, nonlinear models outperformed their linear counterparts, with

Random Forest achieving a test mean absolute error of 77.8, while XGBoost

further improved it to 71.4. The success of tree-based models indicates that

named entities (person and

place names) contain nontrivial temporal signals that can be effectively

captured through decision tree splits.

The deep learning approach using a neural network produced an even lower mean

absolute error of 48, confirming that neural networks can model intricate

data structures more effectively than traditional methods. Notably, the

10-fold cross-validation on the neural network yielded a similar mean

absolute error of 49.78, indicating that the model generalizes well across

different data subsets.

Finally, among the ensemble models evaluated, the 10-Fold Ensemble, which is

the weighted average of predictions from all neural network 10-fold models

that optimized overall regression performance, achieved the lowest mean

absolute error of 45.7, indicating its superior accuracy in minimizing

prediction errors (Table 1).

However, the RF + XG + LGBM + NN Ensemble demonstrated the highest R² value

of 0.9277 (see Table 1 and Table 2), signifying its ability to explain the

largest proportion of variance in the target variable (predicted year of

authorship) while still maintaining a competitive mean absolute error of 47.

Although the 10-Fold Ensemble slightly outperforms in terms of absolute

error, the RF + XG + LGBM + NN Ensemble provides a strong balance between

accuracy and predictive power, making it the best overall model for

historical text dating.

6.2. Cross-Validation and Generalization

The study highlights the importance of cross-validation in ensuring model

generalization. Lasso and Ridge regression models were evaluated using

5-fold cross-validation, while Random Forest underwent 5-fold

cross-validation with hyperparameter tuning via GridSearch. The use of

cross-validation helped mitigate overfitting and provided a more reliable

estimate of model performance. In contrast, the SVM and XGBoost models were

optimized using manual hyperparameter tuning. The ensemble models, which

combined multiple predictions, were evaluated using weighted averaging

techniques to leverage the strengths of individual models while minimizing

their weaknesses.

The results from cross-validation further validate the importance of

nonlinear models for this task. The neural network model achieved an average

mean absolute error of 49.78 across its 10 validation folds, demonstrating

its ability to generalize well to unseen data. The Random Forest model also

benefited from cross-validation through hyperparameter tuning with

GridSearch, leading to optimized results with improved generalization

performance.

6.3. Importance of Model Selection in Historical Text Dating

A key insight from this study is the necessity of choosing models that align

with the dataset’s structure. The poor performance of linear models

underscores the presence of nontrivial patterns in historical text data. The

significant improvement achieved by nonlinear models such as XGBoost and

Random Forest highlights the importance of ensemble learning in predicting

authorship dates. These models reduced the mean absolute error from over 120

years (Lasso and Ridge) to around 71 for XGBoost and 77 for Random

Forest.

The best performing models were the ensemble approaches, which combined

Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM, and Neural Network. The 10-Fold Ensemble

model (refer to section 6.1) achieved the lowest mean absolute error of 45.7

years, confirming that ensemble learning is beneficial for capturing the

complex relationships within historical text data.

6.4. Future work

As the current model relies primarily on named entities, which limits the

scope of information used for predictions, future work could incorporate

additional features such as text metadata, stylistic elements, or linguistic

analysis to better capture cultural and historical context. Incorporating

features related to language style, sentence structure, or thematic elements

could provide a richer dataset, leading to more accurate predictions.

While nonlinear models performed well, further improvements could be achieved

through more extensive hyperparameter tuning. Techniques such as grid

search, random search, or Bayesian optimization could refine model

parameters and enhance predictive accuracy. Additionally, exploring

different neural network architectures, activation functions, and training

strategies may reveal more optimal solutions. Future research could also

integrate probabilistic modeling techniques or deep learning approaches that

could provide a more nuanced way to manage date uncertainty, offering

confidence intervals rather than single-year predictions.

Moreover, the lack of cross-validation for support vector machine and XGBoost

suggests that further evaluation using systematic validation methods could

enhance reliability, particularly in cases where performance varied across

historical periods.

By refining and expanding this computational approach, this research advances

the field of digital humanities and historical text analysis. The ability to

date historical texts with greater accuracy and efficiency offers scholars

and archivists a powerful tool for preserving and understanding historical

narratives. With continued improvements in feature engineering, modeling

techniques, and dataset expansion, machine learning-based approaches have

the potential to revolutionize historical manuscript dating and related

fields.

7. Conclusion

This study developed a machine learning regression model to predict the

authorship dates of historical texts using named entities, specifically person

and place names, as temporal markers. Unlike traditional historical manuscript

dating methods, which rely on physical examination, paleographic analysis, or

expert interpretation, this approach introduces a scalable and non-destructive

alternative capable of efficiently processing large textual datasets. The key

contribution of this work is the demonstration that named entities can serve as

effective temporal indicators, providing a novel feature set for dating

historical texts. By structuring the dataset as a one-hot encoded matrix of

named entities and implementing regression techniques, this study introduces a

computational framework that refines the estimation of textual origins.

The results highlight that the model performs well in predicting exact years for

texts where definitive dates are available. Linear models such as Lasso and

Ridge Regression struggled to capture the complexities of the data, resulting in

poor performance. In contrast, nonlinear models, including Random Forest and

XGBoost, significantly outperformed linear methods by effectively modeling

intricate patterns. To further enhance predictive accuracy, deep learning

approaches using neural networks were explored, demonstrating competitive

performance and scalability for larger datasets. Among all models tested, the

ensemble approach proved to be the most effective, capturing the most variance

and achieving the highest predictive accuracy. With a mean absolute error of

45.75 years, the 10-fold ensemble (refer to section 6.1) model successfully

estimated authorship dates within a reasonable margin, demonstrating its

potential for historical text dating.

Challenges arose when dealing with texts containing anachronistic references or

names persisting across long historical spans, leading to occasional

misclassifications. Additionally, while this approach demonstrated reasonable

predictive accuracy, some degree of error persisted, particularly for texts with

limited historical context or insufficient named entity occurrences.

Despite these promising findings, several areas for improvement remain. The

assumption that named entities alone are reliable indicators of time is not

always valid, as historical figures and locations can appear in texts written

long after their referenced period. Furthermore, the accuracy of historical name

annotations in the dataset directly impacts model performance, introducing

potential noise. Handling texts with uncertain date ranges also presents an

ongoing challenge, requiring further methodological refinement to account for

temporal ambiguity.

The modeling approach used in this study, using text-derived features to date

historical texts, can be applied broadly across digital humanities datasets.

Many humanities corpora share structural similarities: They contain named

entities, locations, chronological indicators, and stylistic patterns that vary

across authors, regions, or time periods. Models like the one used here can help

uncover latent structure within these features, enabling researchers to detect

authorship signals, identify regional or administrative variations, trace

linguistic change, or predict missing metadata such as date, provenance, or

genre. Because the framework is feature-centric and interpretable, it is

well-suited for historical corpora where transparency and scholarly

justification are essential. Therefore, similar workflows could support research

in areas such as epigraphy, manuscript studies, or historical newspaper

analysis, allowing scholars to systematically explore patterns that are

difficult to see through manual inspection alone.

Works Cited

Assael et al. 2025 Assael, Y., Sommerschield, T.,

Cooley, A., Shillingford, B., Pavlopoulos, J., Suresh, P., Herms, B., Grayston,

J., et al. (2025)

“Contextualizing ancient texts with

generative neural networks”,

Nature,

645(8079), pp. 141–147. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09292-5.

Broux and Depauw 2015 Broux, Y., and Depauw, M.

(2015) “Developing onomastic gazetteers and prosopographies

for the ancient world through named entity recognition and graph

visualization: Some examples from trismegistos people”, in L. Aiello

and D. McFarland (eds.) Social Informatics. SocInfo 2014.

Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Vol. 8852). Springer,

Cham.

Castro et al. 2004 Castro, K., Vandenabeele, P.,

Rodríguez-Laso, M., Moens, L., De Schryver, S., and Van Hooydonk, G. (2004)

“Micro-raman analysis of coloured lithographs”,

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry,

379(5-6), pp. 674–683.

Depauw 2018 Depauw, M. (2018) “Trismegistos. optimizing interoperability for texts from the

ancient world”, in A. De Santis and I. Rossi (eds.) Crossing Experiences in Digital Epigraphy. From Practice to

Discipline. De Gruyter, pp. 191–199.

Depauw and Van Beek 2009 Depauw, M., and Van

Beek, B. (2009) “People in Greek documentary papyri. First

results of a research project”, The Journal of

Juristic Papyrology, 39, pp. 31–47.

Dhali et al. 2020 Dhali, M.A., Jansen, C.N., de

Wit, J.W., and Schomaker, L. (2020)

“Feature-extraction

methods for historical manuscript dating based on writing style

development”,

Pattern Recognition

Letters, 131, pp. 413-420. Available at:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167865520300386.

Hamid et al. 2018 Hamid, A., Bibi, M., Siddiqi,

I., and Moetesum, M. (2018) “Historical manuscript dating

using textural measures”, in 2018 International

Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology (FIT), pp.

235-240.

Han et al. 2023 PLACEHOLDER

He et al. 2014 He, S., Sammara, P., Burgers, J., and

Schomaker, L. (2014) “Towards style-based dating of

historical documents”, in 2014 14th

International Conference on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition,

pp. 265-270.

Hellwig 2019 Hellwig, O. (2019) “Dating Sanskrit texts using linguistic features and neural

networks”, Indogermanische Forschungen,

121, pp. 1-27.

Jull et al. 1995 Jull, A.J.T., Donahue, D.J.,

Broshi, M., and Tov, E. (1995) “Radiocarbon dating of

scrolls and linen fragments from the Judean desert”, Radiocarbon, 37(1), pp. 11–19.

Koopmans et al. 2024 Koopmans, L., Dhali, M.A.,

and Schomaker, L. (2024)

“Performance analysis of

handwritten text augmentation on style-based dating of historical

documents”,

SN COMPUT. SCI., 5(397).

Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-024-02688-6.

Kumar et al. 2011 Kumar, A., Lease, M., and

Baldridge, J. (2011)

“Supervised language modeling for

temporal resolution of texts”, in

Proceedings of

the 20th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge

Management. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery,

pp. 2069–2072. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1145/2063576.2063892.

Moscato et al. 2022 Moscato, V., Craig, H.,

Haque,M.N., Huang, K., Sloan, J., and Corrales de Oliveira, J. (2022)

“Multiple regression techniques for modelling dates of first

performances of Shakespeare-era plays”,

Expert

Systems With Applications, 200, 116903. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.116903

Omayio et al. 2022 Omayio, E.O., Indu, S., and

Panda, J. (2022)

“Historical manuscript dating: Traditional

and current trends”,

Multimedia Tools and

Applications, 81, pp. 31573–31602. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-12927-8

Pavlopoulos et al. 2024 Pavlopoulos, J.,

Konstantinidou, M., Marthot-Santaniello, I., Essler, H., and Paparigopoulou, A.

(2024)

“Dating Greek papyri with text regression”, in

Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the

Association for Computational Linguistics. Toronto, Canada:

Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 1–12. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2023.acl-long.556

Ren et al. 2023 Ren, H., Wang, H., Zhao, Y., and

Ren, Y. (2023)

“Time-aware language modeling for historical

text dating”, in H. Bouamor, J. Pino, and K. Bali (eds.)

Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics:

EMNLP 2023. Singapore: Association for Computational Linguistics,

pp. 13646–13656. Available at:

https://aclanthology.org/2023.findings-emnlp.911/.

Ullah and Jamjoom 2022 Ullah, Z., and Jamjoom, M.

(2022)

“An intelligent approach for Arabic handwritten

letter recognition using convolutional neural network”,

PeerJ Computer Science, 8, e995. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.995.

Van Schaik 2013 Van

Schaik, S. (2013) “Dating early Tibetan manuscripts: A

paleographical method”, Scribes, Texts and

Rituals in Early Tibet and Dunhuang, pp. 119–135.

Wahlberg et al. 2016 Wahlberg, F., Wilkinson,

T., and Brun, A. (2016)

“Historical manuscript production

date estimation using deep convolutional neural networks”, in

2016 15th International Conference on Frontiers in Handwriting

Recognition (ICFHR), pp. 205-210. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICFHR.2016.0048

Yu and Huangfu 2019 Yu, X., and Huangfu, W. (2019)

“A machine learning model for the dating of ancient

Chinese texts”, in

2019 International Conference

on Asian Language Processing (IALP), pp. 115-120. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1109/IALP48816.2019.9037653