Open Tool Registries! Resolving the Directory Paradox with Wikidata

Abstract

This paper introduces the conceptual framework for open and community-curated tool registries, posing that such registries provide fundamental value to any field of research by acting as curated knowledge bases about a community’s past and current methodological practices as well as authority files for individual tools. The modular framework of a basic data model, SPARQL queries, bash scripts, and a prototypical web interface builds upon the well-established and open infrastructures of Wikimedia, GitLab, and Zenodo for creating, maintaining, sharing, curating, and archiving linked open data. We demonstrate the feasibility of this framework by introducing our concrete implementation of a tool registry for digital humanities, initially repurposing data from existing silos, such as TAPoR and the SSH Open Marketplace, and retaining the established TaDiRAH classification scheme while being open to communal editing in every aspect.

Introduction

Tool Registries in the Digital Humanities

Yet another tool registry?

Design goals

Core components

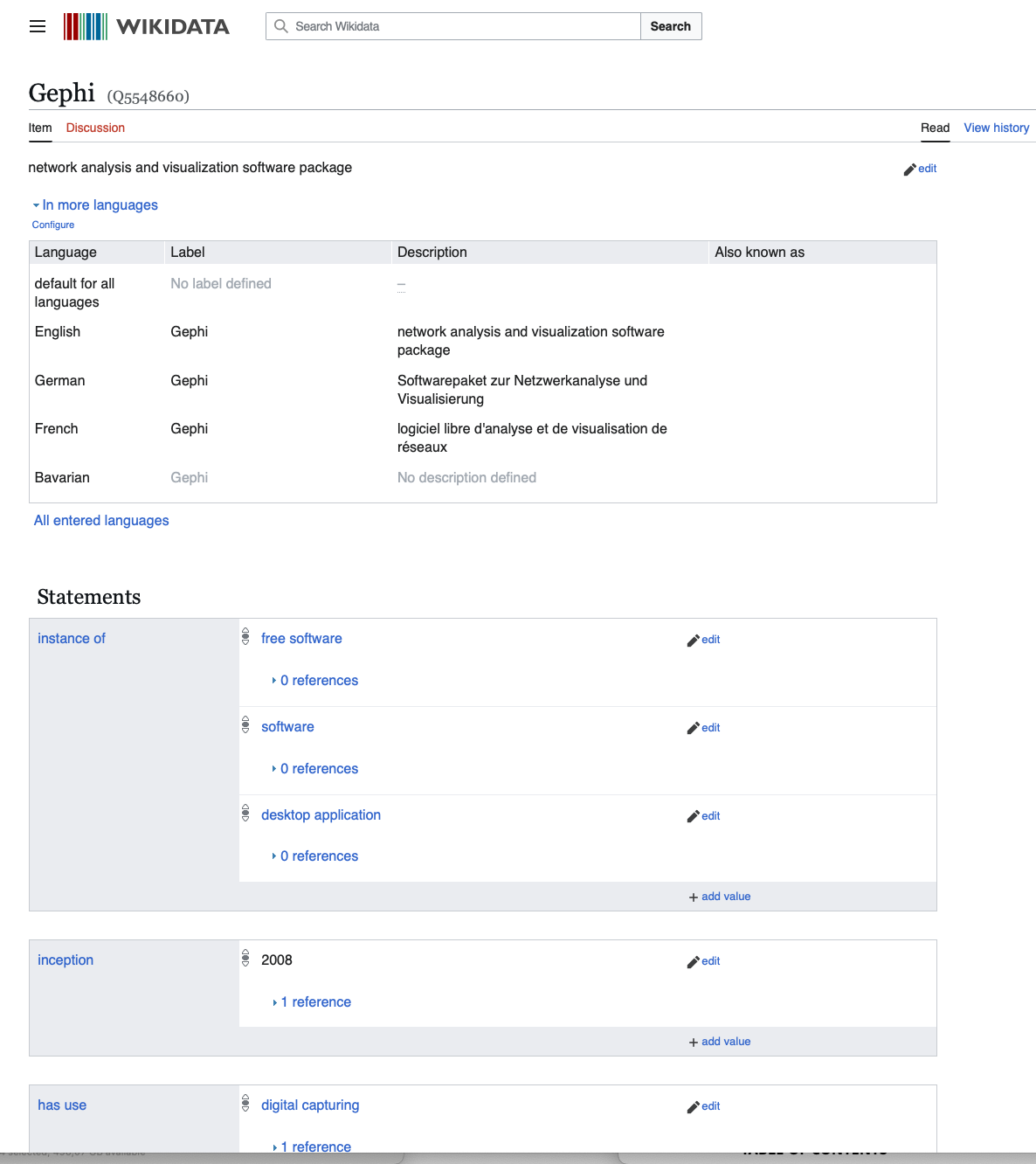

Wikidata

- Data are available on the web with a public domain licence (CC0);

- Data are machine-readable structured data;

- Data are serialised in non-proprietary formats;

- Data adhere to open standards; and

- Data link to other people’s data to provide context.

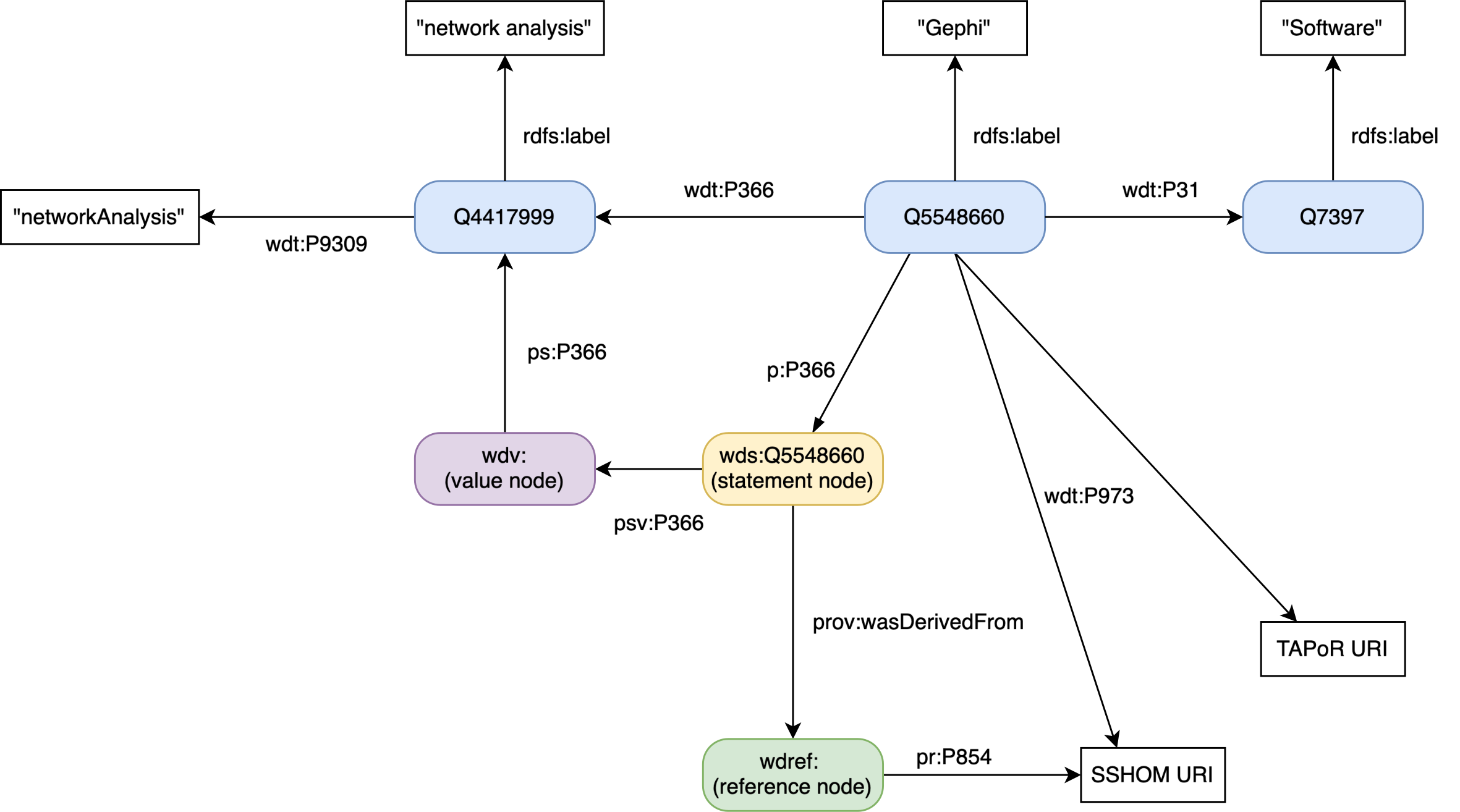

Data models

Our basic data model

- Research tools comprise both methods and concrete software.

- Methods are informed by theories and have a purpose.

- Methods are implemented through (multiple) layers of software, which, in turn, require hardware and infrastructural resources such as electricity, internet connectivity or licences and which interact with data formats and serialisations (reading and writing).

- Software is written in programming languages and can be interacted with through interfaces. Command line interfaces and application programming interfaces require knowledge of programming languages to interact with them.

- Methods, languages, and formats rely on and implement abstract concepts.

TaDiRAH mapping

- Development depends on voluntary labour and thus the vocabulary has been dormant for a number of years.

- The current version and its documentation have been hard to find. Until September 2025, when the team finally updated the GitHub repository to v2.0, search engines usually returned the incompatible v0.5 (see also [Zhao 2022]).

- The SPARQL endpoint and API, which would serve the classification scheme as RDF, are frequently down.

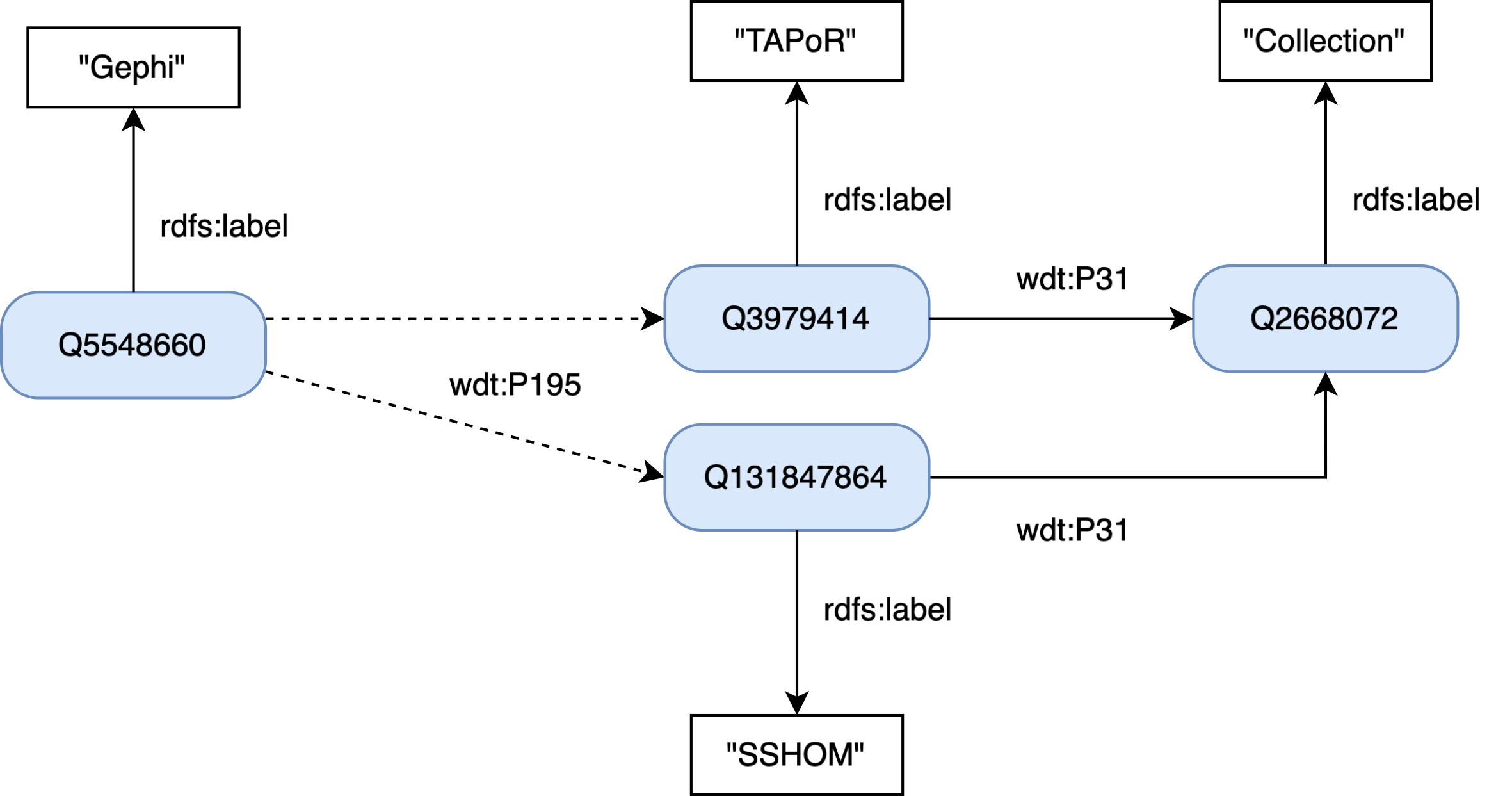

Optional parts of the basic data model and curating collections of tools

Domain-specific extensions

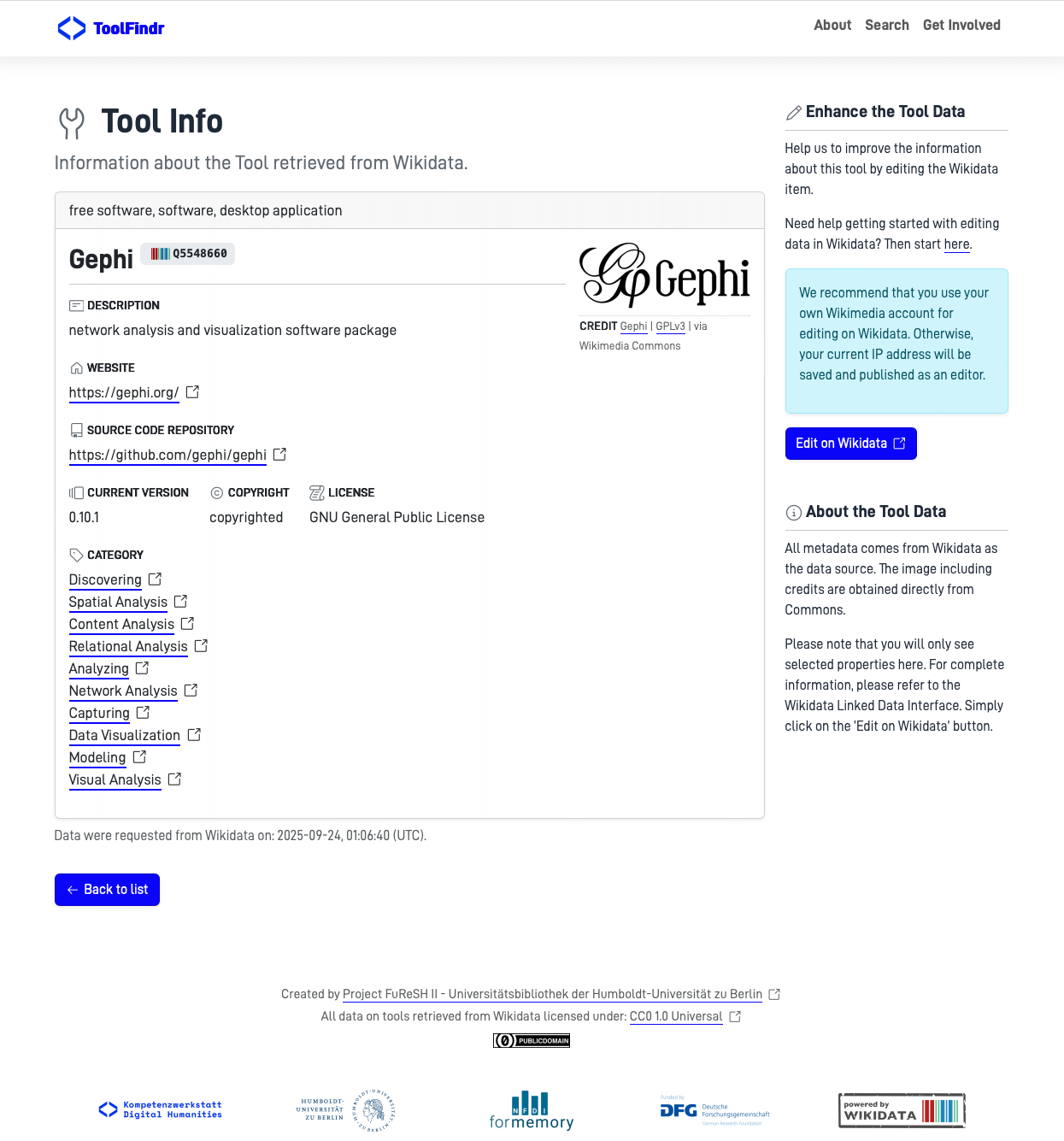

Frontends

Query tools with SPARQL

This query returns the IDs of items and their labels as a potential sanity check for human readers. The ID can then be used in further SPARQL queries, API calls, or the plethora of tools for interacting with Wikidata hosted on Toolforge, ranging from Scholia, a long-running project for querying and visualising scientometrics [Nielsen, Mietchen, and Willighagen 2017], to Reasonator, which displays Wikidata items in a view optimised for their particular item-type and enhanced with some basic reasoning.SELECT DISTINCT ?tool ?toolLabel # only get Software-ID and Software-Name WHERE { ?method wdt:P9309 ?tadirahID. # Variable method is a tadirah-method ?tool wdt:P366 ?method; # Variable tool 'has method' method (wdt:P31/(wdt:P279*)) wd:Q7397. # and tool is child of "Software" SERVICE wikibase:label { # set wikibase-service to auto-language with fallback english bd:serviceParam wikibase:language "[AUTO_LANGUAGE],en". # get the tool-label (=name) of our tool. ?tool rdfs:label ?toolLabel. } }

However, writing and adapting such queries require a profound knowledge of the SPARQL query language, which makes it difficult to use for many, if not most potential users. A number of research teams are testing the application of LLMs or LLM-based systems for interacting with knowledge graphs and SPARQL endpoints in natural language with promising results [Rony et al. 2022] [Taffa and Usbeck 2023] [Liu et al. 2024] [Rangel et al. 2024]. All current LLMs are pretty good at generating syntactically correct SPARQL but cannot be relied upon to correctly identify entities and properties of any given knowledge graph. Based on our anecdotal testing, the prototypical SPINACH chat bot, which was specifically designed for querying Wikidata with SPARQL, outperforms any general purpose LLM and is a great entry point for those with only cursory knowledge of SPARQL [Liu et al. 2024]. As always, one needs to check the suggestions for plausibility and the more specific the natural language instructions, the better will be the results.#title:Tools in the SSHOM #defaultView:Table PREFIX collection:<http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q131847864> # a specific collection SELECT ?tool ?toolLabel WHERE { ?tool wdt:P195 collection: ; # items in the collection wdt:P31/wdt:P279* wd:Q7397. # limit tools to software in the broadest sense SERVICE wikibase:label bd:serviceParam wikibase:language "[AUTO_LANGUAGE],en". ?tool rdfs:label ?toolLabel. } } LIMIT 3000

Tool Registry Frontend Module

Data and Workflows

Data sources

Data import

Adding and editing data

Export and publication of stable data sets

Discussion and outlook

Acknowledgments

Funding

Author contributions (CRediT)

- Conceptualization: Till Grallert, Sophie Eckenstaler, Claus-Michael Schlesinger

- Data Curation: Till Grallert, Isabell Trilling

- Investigation: Till Grallert, Sophie Eckenstaler, Isabell Trilling, Sophie Stark

- Software: Sophie Eckenstaler (Frontend, SPARQL), Nicole Dresselhaus (Archiving), Till Grallert (SPARQL, R)

- Writing, original draft: Till Grallert, Claus-Michael Schlesinger, Sophie Eckenstaler, Nicole Dresselhaus

- Writing, review & editing: Till Grallert, Claus-Michael Schlesinger

Data availability

- SPARQL queries: [Grallert 2024].

- Data model and JSON schemas for use with OpenRefine: https://scm.cms.hu-berlin.de/methodenlabor/p_publish2wikidata.

- Front end: [Eckenstaler and Schlesinger 2025].

- Weekly screenshots of the data set as exported from Wikidata: (Grallert and Dresselhaus, 2024–).