Abstract

It is sometimes said that all politicians sound the same with their speeches mired

in political jargon full of clichés and false promises. To investigate how distinct

the plenary speeches of political parties truly are and what linguistic features make

them distinct, we trained a BERT classifier to predict the party affiliation of Finnish

members of parliament from their plenary speeches. We contrasted and compared model

performance to human responses to see how humans and the model differ in their ability

to distinguish between the parties. We used the model explainability method SHAP to

identify the linguistic cues that the model most relies on. We show that a deep learning

model can distinguish between parties much more accurately than the respondents to

the questionnaire. The SHAP explanations and questionnaire responses reveal that whereas

humans tend to rely on mostly topical cues, the model has learned to recognize other

cues as well, such as personal style and rhetoric.

Introduction

Language is a fundamental part of doing politics. The way laws are enacted, debates

held, and manifestos written are all deeply entrenched in rhetoric and discourses

that are both rooted in their time and take inspiration from the past. Scholars such

as Edelman claim that

“political language is political reality” ([

Edelman 1988, 104])

[1]

while Rubinelli says that

“the language of politics is essentially rhetorical” [

Rubinelli 2018, 27]. Politics are done through language and, thus, through language, we can make

inferences about the underlying ideological motivations of political actors. Being

able to differentiate between political parties is an important aspect of civil competence,

since informed citizens are recognized as the cornerstone of a functioning democratic

system, especially when it comeswith regard to political and civic participation [

Coverse 1975]. Although many studies have shown that the citizens’ factual knowledge of politics

shows remarkable variation ([

Delli Carpini and Keeter 1991 ]; [

Elo and Rapeli 2010]), trusted sources of information - for example friends, schoolmates, colleagues,

parties, educational institutions - play an important role as ‘shortcuts’ used to

compensate gaps in factual knowledge [

Iyengar 1990]; [

Lupia 1994].

In this paper, we research how distinct Finnish political parties are in their parliamentary

rhetoric by contrasting the performance of a BERT classifier, trained to predict the

party affiliation of a member of parliament given one of their speeches, to human

performance ion the same task. More precisely, we use FinBERT, a Finnish base model

built on the Transformer architecture that we fine-tune for our specific task using

the

FinParl corpus of plenary speeches of the Finnish Parliament [

Hyvönen et al. 2021]. We use the model explainability method SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to

examine the linguistic features that make the speeches distinct and extract party

specific keywords that reflect the words that are most important for the model in

its decision-making process. We then compare model performance to human performance

by examining responses to a questionnaire in which 438 participants are asked to identify

parties based on plenary speeches.

Our research questions are as follows:

- How distinctive are Finnish political parties based on their parliamentary speeches

for a machine learning model?

- How well do human respondents perform in distinguishing between the parties compared

to the model?

- How do the model and human respondents differ with regards to the linguistic features

that they use distinguish between the parties?

The Finnish parliament is an interesting subject to study because, as a multiparty

parliament, the differences between party policies are more subtle than in a two-party

parliament, which requires more nuanced understanding to distinguish between them.

So far,To date, most similar studies have been conducted on parliaments with fewer

parties. This also makes the use of a Transformer model more appealing, as they have

been shown to be much more accurate than simpler models in a number of tasks. Our

results should be of great interest to those working in the fields of political science,

computational social science and digital humanities, as it highlights the value of

model explainability methods, which are infrequentlynot much used in these fields.

Using deep learning combined with state-of-the-art model explainability methods, we

contribute to a deeper understanding of what makes political speech distinguishable.

The comparison between model explanations and human responses reveals further details

about the distinctiveness of plenary speeches and about the differences of cues identified

by humans and machine learning models. We show that the model can make predictions

on very different cues than humans.

Background and previous work

Finnish parliament

The Finnish parliament (Suomen eduskunta) is a one chamberunicameral parliament with 200 members of parliament (MPs) elected

in a general election every four years. The two official languages of Finland, Finnish

and Swedish, are also the official languages used in parliament, although, in practice,

only around 1-2% of speeches contain some Swedish. The government is typically formed

as a coalition of parties with the leader of the party holding most seats assuming

the role of prime minister. Although dozens of parties have appeared and disappeared

from Finnish politics during over athe more than a hundred years of democracy, from

the 1980s to 2011 there were three major parties: the Social Democratic Party (sosialidemokraattinen puolue, SDP), the National Coalition party (kokoomus, KOK) and the Centre Party (keskusta, KESK). In 2011, the meteoric rise of the Finns party (perussuomalaiset, PS) disrupted the status quo as the Finns overtook the Centre Party as the third largest

party in parliament. Smaller parties consistently present in parliament are the Left

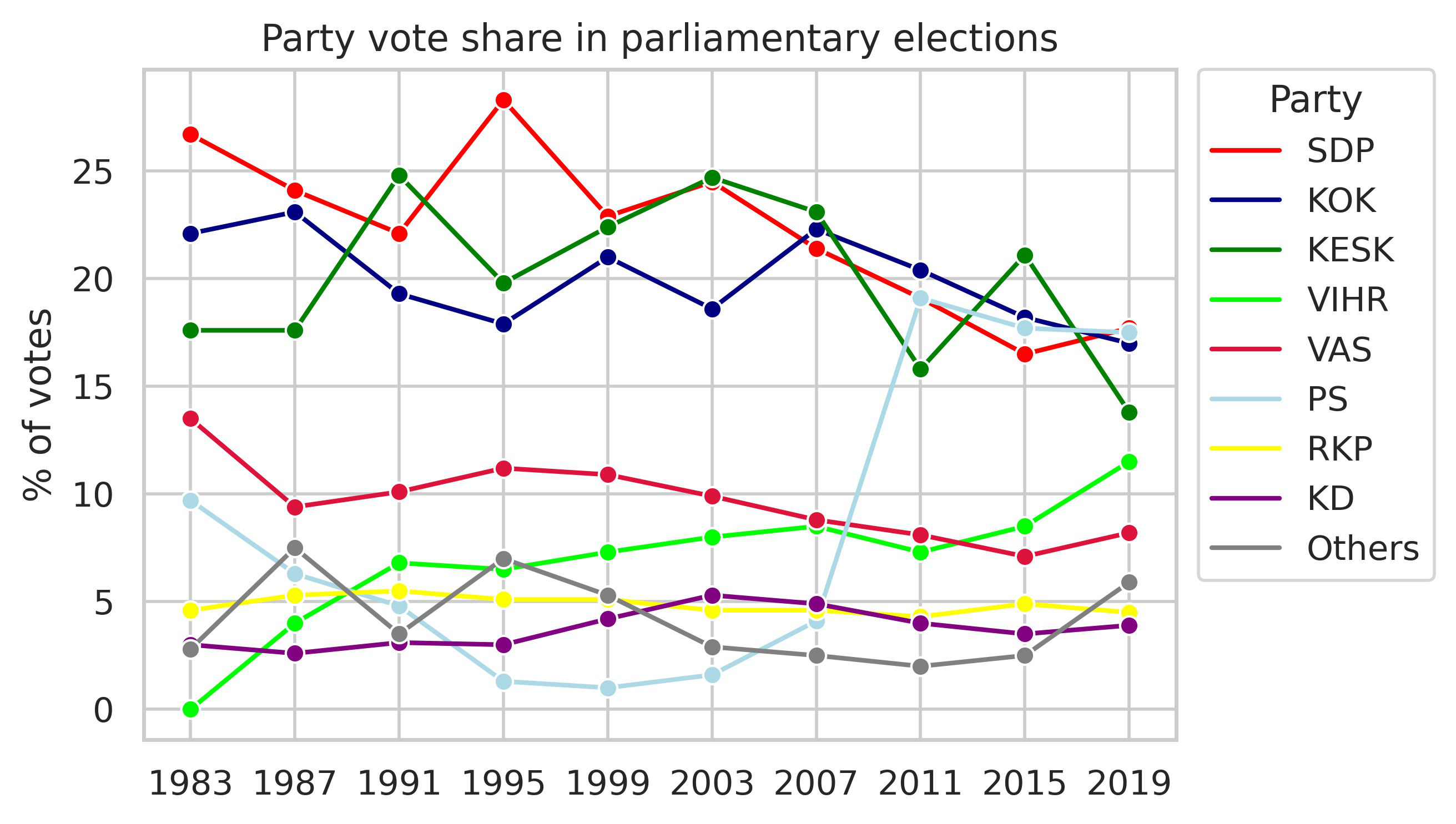

Alliance (vasemmistoliitto, VAS), the Green Party (vihreät, VIHR), the Swedish People’s Party (ruotsalainen kansanpuolue, RKP), and the Christian Democrats (kristillisdemokraatit, KD). Figure 1 shows the election results in Finnish parliamentary elections since 1983.

Plenary sessions (

eduskunnan täysistunto) include a variety of sections and agendas. Legislation is debated and enacted regularly

and, once a week, ministers have to answer oral questions from MPs during Question

Time (Finnish Parliament, n.d.). Plenary sessions are open to the public and are also

broadcast online (Finnish Parliament, n.d.). Although, formally, plenary speeches

are directed at the chairman, with speeches typically beginning with a direct address,

e.g.

Arvoisa puhemies [Honoured chairman], they are still audience oriented, heldgiven with fellow MPs,

media and the electorate in mind (Ilie, 2018). The Finnish parliament is what is known

as a working parliament as opposed to a debate parliament. This means that the most

heated debates are often held behind closed committee doors whereas plenary sessions

tend to be less confrontational. Compare This stands in contrast tothis to debate

parliaments, such as the UK House of Commons, in which lively public debates are commonplace

[

Ilie 2018]. The Finnish parliament is also considered to follow a consensual system ([

Gallagher et al. 2006]) because committee work, and coalition governments require co-operation between

members from different parties. This can potentially make distinguishing political

speeches in Finland more difficult than in countries with more confrontational parliamentary

cultures, since increased partisanship and politically extreme rhetoric has been shown

to make party affiliation easier to distinguish for machine -learning models [

Bayram, Pestian, Santel 2019];

#santel_minai2019; [

Diermeier et al. 2011].

All speeches held in the plenary sessions are transcribed. The transcriptions of are

close-to-verbatim documentations of the original. In principle, all speeches are presented

as spoken. However, the secretaries are allowed to standardizse phonological expression

or to remove expletives whenever needed to make the transcriptions more readable and

understandable. During the entire history of Finnish parliamentarism, the transcriptions

have sought striven to document what has been said in plenary sessions. Today, the

transcriptions are made according to detailed instructions and guidelines of the

eduskunta [

Voutilainen 2016].

Previous work on predicting party affiliation

Renáta Németh (2023) has conducted a review of recent publications that use Natural

Language Processing (NLP) methods to study political polarization. She found that

the number of new publications is on the rise and that most of these studies use data

from the United States and Twitter and present data from a short period of time. Of

the studies that she reviewed five use a classification approach, most use bag-of-words

models and only three discuss, which linguistic features affect classification. Some

studies (see e.g., [

Bayram, Pestian, Santel 2019]; [

Hirst et al. 2010]; [

Peterson and Spirling 2018]) use classification performance as a measure of party polarization, i.e., good performance

means high polarization. We believe that as polarization refers to two opposing entities,

it does not fit the Finnish political setting. We are skeptical sceptical of using

classifier performance as a direct measure of polarization because, as our results

and previous research (e.g. [

Hirst et al. 2010]; [

Potthast et al. 2018]) show, the linguistic features that drive classifiers like ours are not necessarily

politically or ideologically motivated. For these reasons, we opt to use the more

suitable term

distinctiveness.

Previous studies on predicting party affiliation from parliamentary speeches include

work on the United States’ ([

Bayram, Pestian, Santel 2019]), Lithuanian ([

Kapočiūtė-Dzikienė and Krupavičius 2014]), Norwegian ([

Søyland and Lapponi 2017]), and Danish ([

Navaretta and Hansen 2020], [

Navaretta and Hansen 2024]) parliaments. These studies use a number of different models to predict party affiliation

in varying political contexts. [

Bayram, Pestian, Santel 2019] trained several binary classifiers on data from the U.S. Congress and achieved 78

% accuracy with a Support Vector Machine (SVM). They trained the classifiers on 7

different congresses and used model accuracy as a proxy measure for partisanship across

time. They assumed more partisanship means that the two parties are more distinct

in their rhetoric and, thus, easier to classify. [

Peterson and Spirling 2018] show that this method gives results that correspond to conventional knowledge of

polarization in the British parliament. [

Diermeier et al. 2011] examined both politically extreme and politically moderate Republicans and Democrats

in the U.S. senate. Their results show that their SVM classifier did not distinguish

was worse at distinguishing between moderate senators thanas well as more extreme

ones, showing that more ideologically distinct politicians are easier to distinguish.

A feature analysis shows that senators were distinguishable on economic and moral

issues. The paper also shows some evidence of politically extreme senators using signal

words or dog whistles, which are used as covert messages to the more extreme elements

of the electorate.

Other studies have useduse classifiers in multi-party settings. [

Søyland and Lapponi 2017] trained an SVM classifier on speeches held in the Norwegian parliament. After heavy

preprocessing and adding metadata, their classifier reacheds an F1 score of 0.729

on a dataset with 7 parties. Similarly, [

Navaretta and Hansen 2020] trained several models and reached an F1 score of 0.57 on a 4-class classification

task of Danish parliamentary speeches. [

Kapočiūtė-Dzikienė and Krupavičius 2014] used the Naïve Bayes Multinomial method to classify Lithuanian parliamentary speeches

in two datasets, one containing speeches from 12 parties, the other containing speeches

from 8 parties with different levels of pre-processing. Their method achieveds 49%

accuracy.

[

Hirst et al. 2010] argue that what matters most in party rhetoric is not ideology, but institutional

positioning, i.e., the opposition-government divide. They trained an SVM using data

from the Canadian House of Commons and found that classification accuracy is better

with data from Question Periods than with data from debates. Moreover, they fouind

that when training on one parliament and testing on another in which the government-opposition

roles are flipped,

“the performance of the classifier completely disintegrates” [

Hirst et al. 2010, 739]. They thus argue that their classifier does not distinguish political parties

by ideology but by turns of attack and defence between opposition and government.

[

Navaretta and Hansen 2024] studied the identification of plenary speeches from opposition and government parties

in the Danish parliament by training several models based on different architectures.

They found that fine-tuning a Danish BERT model gave the best performance.

Most of the research discussed above has been conducted on parliaments with fewer

parties than the eight that regularly occupy the Finnish parliament. Thus, our setting

requires the classifier to detect and distinguish more minute differences between

party rhetoric to make correct predictions. The literature in the field shows that

government and opposition roles are reflected in plenary speeches. To mitigate this

effect, we trained our model with data that has all parties occupying both government

and opposition roles. Therefore, the model cannot reliably base its predictions on

linguistic cues caused by this division. Whereas previous studies have mostly used

SVMs and other relatively simple models, our deep learning model has the potential

to reveal previously unknown distinctive linguistic features of plenary speeches due

to it relying on context-aware word embeddings rather than bag-of-words-style features.

We also trained an SVM as a baseline comparison and show that the BERT model performs

better.

Cues and voter assessment of political parties

A voter’s ability to understand current affairs and to identify major ideological

differences is considered central for their political competences, i.e., for

“understanding of processes and structural components associated with developing public

events” [

Genova and Greenberg 1979, 89]. This links our current study to the broader field of research on civic competence

and political knowledge (e.g., [

Dahl 1992]; [

Delli Carpini and Keeter 1993]; [

Downs 1957]; [

Popkin and Dimock 1999]). A majority of studies on citizens’ ability to identify and assess political issues

focus on the impact of a party’s policy positions on citizens’ the voting behaviour

of citizens. [

Devroe 2020], for example, studieds voter assessment of a candidate’s competence based on the

candidate’s gender, some biographical information, as well as their policy position

on selected issues. The results indicate that voters tend to give positive evaluation

to candidates with similar policy positions. [

Adams, Weschle, and Wlezien 2021], in turn, show that voters tend to consider parties that appear cooperative to each

other

“as sharing more similar ideologies than those that exhibit conflictual relationships” [

Adams, Weschle, and Wlezien 2021, 112]. The study of [

Valentino et al. 2002] presents mixed conclusions about the impact of political cues. On the one hand,

voters being aware of such cues seem to be able to change their attitudes. On the

other, however, without an appropriate knowledge of politics, cues might be left unidentified

and negative cues unchallenged. The role of political knowledge and the proper understanding

of different party preferences are recognised by [

Gilens 2001], [

Tilley and Wlezien 2008], and [

Just 2022]. These studies bring upraise evidence that new policy-specific information and raw

facts might have a strong influence in the shaping of political judgements of party

placements and positions.

To sum upsummarize, a majority of former studies argue that a proper identification

of ideological positions is strongly dependent on citizens’ political knowledge and

their ability to recognise and use ideational cues. Put other way roundConversely,

analysing citizens’ ability to correctly classify plenary speeches to ideological

positions represented by different parties can help us to better understand how well

citizens are able to identify the vocabulary of politics and link its use to ideologies

underlying the party system.

Data & Methods

In this section, we introduce the FinParl dataset and how we built our corpus of speeches.

Next, we explain the basic principles of text classification with deep learning models.

Third, we show how the model explainability method SHAP provides explanations to the

predictions made by a machine learning model. Finally, we explain our experimental

setup, including how we trained our model, how we extracted SHAP explanations and

how the questionnaire was structured.

FinParl dataset and pre-processing

The data used for this research was obtainedcomes from the FinParl dataset, which

consists of parliamentary speeches held in the Finnish

eduskunta since its inception in 1907 [

Hyvönen et al. 2021]. From the years 1907 to 1999, the data is digitised using OCR, whereas later data

was collected from HTML and XML files. The contents of the dataset and how it was

created is explained in detail in [

Sinikallio et al. 2021]. In the current paper, we focus on speeches from 2000 to 2021.

We converted the data into CSV format containing the full text of the speech, the

speaker’s name, the party affiliation and the year. Speeches that were interrupted

and were thus separated into two or more segments, were combined, while the interruptions

themselves were discarded. While we aimed to keep as much of the original data as

possible so as not to introduce bias in the results, some filtering was applied where

it was deemed necessary. Speeches with the speaker tag ’chairman’, ’viceChair’, ’secondViceChair’

or ’elderMember’ were discarded, since they mainly consisted of formal boilerplate

text rather than ideologically motivated political speech. The data were further cleaned

by removing speeches that were deemed too short. To determine a suitable minimum speech

length, a manual review of deleted material at different cut-off points was conducted.

This led us to remove speeches with 12 tokens (see section on deep learning below) or fewer.

Finally, we removed mentions of party names, because these could make the classification

task trivial, especially in speeches with phrases, such as

Me perussuomalaiset [We, the Finns]. ItThis will also forces the model to make predictions based on other

than these obvious linguistic cues, which could reveal more latent features of party

rhetoric. Party names were removed using the Named-Entity Recognition (NER) model

developed by the National Archives of Finland.

[2]

Entities tagged with either the ORG or NORP tag that matched a party name or abbreviation

were replaced with the string

[PUOLUE], meaning [PARTY].

We did not remove Swedish speeches from the dataset, as the Swedish language holds

a significant cultural and historical place in Finnish society and politics. Swedish

in parliament is today mostly, but not exclusively, used in official communications,

and in everyday political debates by members of the Swedish People’s Party. The Swedish

People’s Party is a major political force in Finland, being a member of all coalition

governments since the 1970s with the exception of one four-year term between 2015

and 2019.

Only speeches from the 8 largest parties from 2000 to 2021 were retainedkept. Short-lived

minor parties such as Remonttiryhmä, who only existed for three years and had one MP, were discarded. The distribution

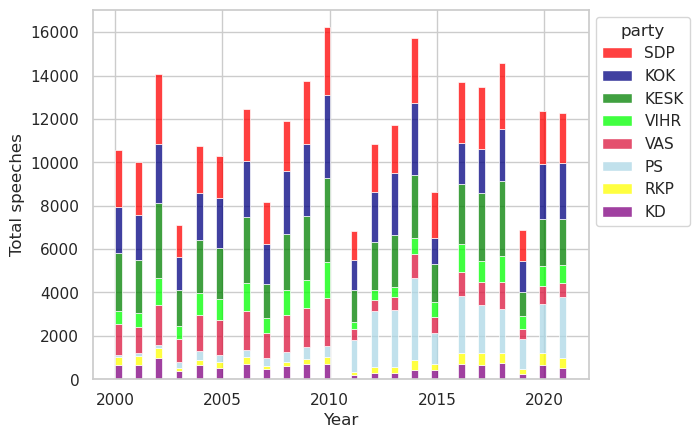

of speeches per party from 2000 to 2021 is shown in Figure 2. The figure shows that

the Social Democrats (SDP), the National Coalition (KOK) and the Centre (KESK) account

for most of the speeches in the dataset, over 50,000 each. The Finns, the Greens and

the Left Alliance account for over 20,000 speeches each, the Christian Democrats for

13,000 and the Swedish People’s party for 7,000. The major leap in vote share of the

Finns (PS) in the 2011 elections is also reflected in the data by an increased share

of speeches. The final dataset has speeches from 605 speakers. The average speaker

has 427 speeches in the dataset, the median being 272. Fifty-three53 speakers have

more than a thousand speeches attributed to them. The two most active speakers are

Erkki Pulliainen from the Green party and Pentti Tiusanen from the Left Alliance with

4525 and 4043 speeches, respectively. The average speech is 219 words long and the

median speech is 130 words long. After pre-processing, the dataset consists of 252,389

speeches.

Text classification using deep learning

Deep learning refers to neural networks that comprise multiple layers of modules that

each represent their input in increasingly abstract form. With sufficientenough layers

and training data, exceedingly complex functions can be learned [

LeCun, Bengio, and Hinton 2015]. BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) is a language representation

model released in 2018 that is built on the Transformer architecture. It performs

much better on many NLPnatural language processing tasks than previously popular models,

such as Support Vector Models [

Devlin et al. 2018]. More recently, Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, Claude and Mixtral

have again changedtransformed the field of the NLP landscape. For many classification

tasks, however, BERT based models are still preferable because LLMs are both computationally

and financially more costly to run.

BERT is trained on a masked language model objective, in which some input tokens are

masked (i.e., hidden), and the model is tasked with predicting the masked token given

both the left and right context. The original BERT model was trained on English and

was soon followed by Multilingual BERT and then other language specific versions.

As the base of our deep learning model, we use FinBERT, a Finnish BERT model pre-trained

on more than 3 billion tokens of Finnish [

Virtanen et al. 2019]. Its high performance in many Finnish NLP tasks makes it the best choice for our

study. We fine-tuned FinBERT for our text classification task using the FinParl data.

BERT models require their input text to be tokenized using a WordPiece algorithm,

first described by [

Schuster and Nakajima 2012]. A BERT model has a fixed vocabulary, with each token being assigned to a unique

token ID. Common words are represented by their own token IDs, but lessfewer common

words are represented by a combination of tokens. For instance, the sequence

"jatkuvasti kasvava byrokratia" ["ever growing bureaucracy"] is tokenized as jatkuvasti, kasvava, byrokra, ##tia.

Additionally, there are a few special tokens, such as [CLS] and [SEP] at the beginning

and end of each sequence. In effect, there are typically somewhat more tokens than

words in any given sequence. Whereas SVMs process input as bag-of-words, with BERT, word

order and context are taken into account. A limitation of the FinBERT model is that

its input cannot exceed 512 tokens, which is why long speeches are truncated to fit

within this limit.

Model explainability

Model explainability is the field of study that examines how the output of machine

learning models can be made understandable to humans. For simple models, the best

explanation can be the model itself, but more complex models require a separate

explanation model to getachieve a human understandable approximation of the model [

Lundberg and Lee 2017]. We use SHAP ([

Lundberg and Lee 2017]) to produce explanations of our deep learning model. SHAP produces explanations

by calculating the contribution that each input feature carries towards the outcome.

For a simplified explanation of how SHAP calculates the contribution of input features,

one can imagine three people digging a hole: A, B, and C. After one hour of digging,

they’vethey have dug a hole one meter deep. To calculate how much each person contributed

to the outcome, we can remove one at a time, dig another hole, and observe the difference.

If we remove person A, the resulting hole is only 0.4 meters deep. Removing B results

in a hole that is 0.5 meters deep. Finally, removing person C results in a hole that

is 1.1 meters deep. Therefore, we can calculate that the effect on hole depth per

person is A = 0.6m, B = 0.5m, C = -0.1m.

SHAP is model agnostic and can be used with tabular, visual or textual data. In practice,

in a text classification setting, each token is treated as a feature, and the outcome

is the prediction that the model produces. SHAP values are calculated by masking sets

of tokens in the model input and observing how the prediction of the model changes

in response. Previous uses of SHAP for text classification explainability include

COVID-19 related fake news detection ([

Ayoub, Yang, and Zhou 2021]) and humour analysis [

Subies et al. 2021]. One major disadvantage of SHAP is that calculating SHAP values for large datasets

is computationally demanding. To reduce the computational load, we use SHAP’s partition

explainer, which clusters tokens together hierarchically and thereby reduces the number

of calculations performed.

Experimental setup

To train our model, we first dividedsplit speeches held between the years 2000 and

2021 into train, development and test sets with 80-10-10 splits. The train and development

splits are used in model training and the test set is used to evaluate the performance

of the model. There are a number of training hyperparameters that need to be set manually

to train a deep learning model, such as learning rate and batch size. We used the

grid search method to optimize model performance. We used label smoothing, a regularisation

technique which prevents models from becoming overly confident, at a factor of 0.1.

This also ensures that the prediction probability of a given prediction is more closely

aligned with actual accuracy (i.e., at 90% prediction probability the model is close

to 90% accurate). To further prevent over-fitting and increase training efficiency,

we used early stopping during the training if the model did not improve its performance

for 10 evaluation calls. Training was done using the Transformers, Tokenizers and

Datasets Python libraries from Huggingface

[3].

To verify that our model performeds consistently, we used 5-fold random subsampling

(see [

Berrar 2019]). This means that five training, development and test sets are created, and each

are used to train a model. The average F1 score of these models is given as the final

performance of the model.

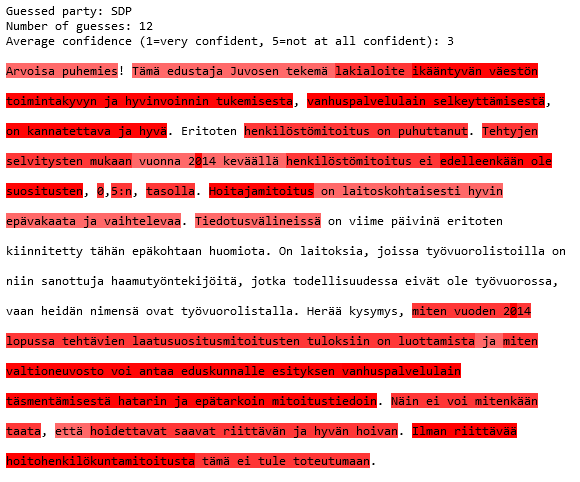

Questionnaire

To groundbase our results oin human performance we created a questionnaire in which

participants were given five speeches to associateconnect with a political party.

In addition to answering which party they believed had given which speech, respondents

were asked to choose the words or phrases that most influenced their decision and

to give a numerical rating on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 = very confident, 5 = not at

all confident) on how confident they were in their answer. Each informant was given

five speeches that were randomly selected from a stratified sample of 100 speeches

that were held between 2010 and 2019 and that were not included in the model training

dataset. We also attained the model predictions for this 100- speech sample. This

way, we could directly compare human performance against machine performance. The

questionnaire was sent to university students as well as circulated online. First,

we collected responses from 166 people, the vast majority of whom were students at

a Finnish university, who were taking a course in Digital Humanities. Later, the questionnaire

was shared by the Finnish national broadcaster Yle, which yielded an additional 272

responses. In total, 438 informants responded to the questionnaire.

Results

In this section, we first analyse the performance of the model quantitatively. We

then analyse the SHAP explanations for a sample of speeches and predictions to ascertainsee

what kinds of linguistic features the model uses to make its predictions. After this,

we turn our focus onto the questionnaire: we examine how well our respondents could

identify the parties and then compare their cues to the SHAP explanations. This comparison

demonstrates how the model and human respondents differ in distinguishing between

the parties.

Model performance

The average macro F1-score from 5-fold random subsampling for our models is 0.66.

As a baseline comparison, we trained an SVM model with lemmatized speeches cleaned

of stopwords, which reached a macro F1-score of 0.58. Using a BERT model shows a clear,

eight-point increase in classification performance, justifying its use in this study

instead of the simpler SVM model.Our fine-tuned FinBERT models achieved an average

macro F1-score of 0.66 across 5-fold random subsampling. As a point of comparison,

we also trained an SVM baseline on lemmatized data with stopwords removed. The SVM

reached a macro F1-score of only 0.58. Fine-tuning FinBERT leads to a substantial

eight-point improvement or a relative gain of nearly 14% in macro F1. Beyond the measurable

performance boost, FinBERT’s contextualized language representations capture nuanced

semantic and syntactic patterns that SVMs with bag-of-words-style features cannot,

making FinBERT a clearly justified choice over the simpler baseline.

To address the 512- token limitation of the FinBERT model, we tested the effect of

keeping the last 512 tokens of speeches exceeding this length instead of the first.

We found the model’s performance to be very similar in both cases. We conclude that

there is no clear difference in distinctiveness between the beginning and the end

of speeches and we feel confident that truncating longer speeches to the first 512

tokens will not affect the results much. Additionally, only approximately 15% of the

speeches exceeded the token limit.

Since some MPs are much more active speakers than others, we consider the fact that

the model might learn the speech patterns and typical word choices of individual MPs.

Therefore, we tested whether the number of speeches an MP has in the dataset affects

how well the model distinguishes that MP’s speeches. We calculated the accuracy of

the model on each speaker and found the accuracy to vary between 0% and 100%, the

average being 57%. Figure 3 illustrates that there is a weak to moderate (Pearsons’

r = 0.35) correlation between the number of speeches and accuracy. Still, many MPs

with few speeches are correctly predicted with high accuracy, while others, such as

Liisa Hyssälä (the Centre, 1,128 speeches) and Peter Östman (Christian Democrats,

896 speeches) are predicted with relatively low accuracy, at 35% and 21%, respectively.

Thus, even though the model has clearly learned to identify the speech patterns of

some speakers, such as MPs Pulliainen and Tiusanen (represented by the two dots in

the top right-hand corner in Figure 3), this is not a universal phenomenon that would

apply to all highly active speakers. NonethelessStill, as we discuss below, the idiosyncrasies

of individual MPs, especially in the case of MP Pulliainen from the Green party, can

have a profound impact on how the model learns to distinguish between parties.

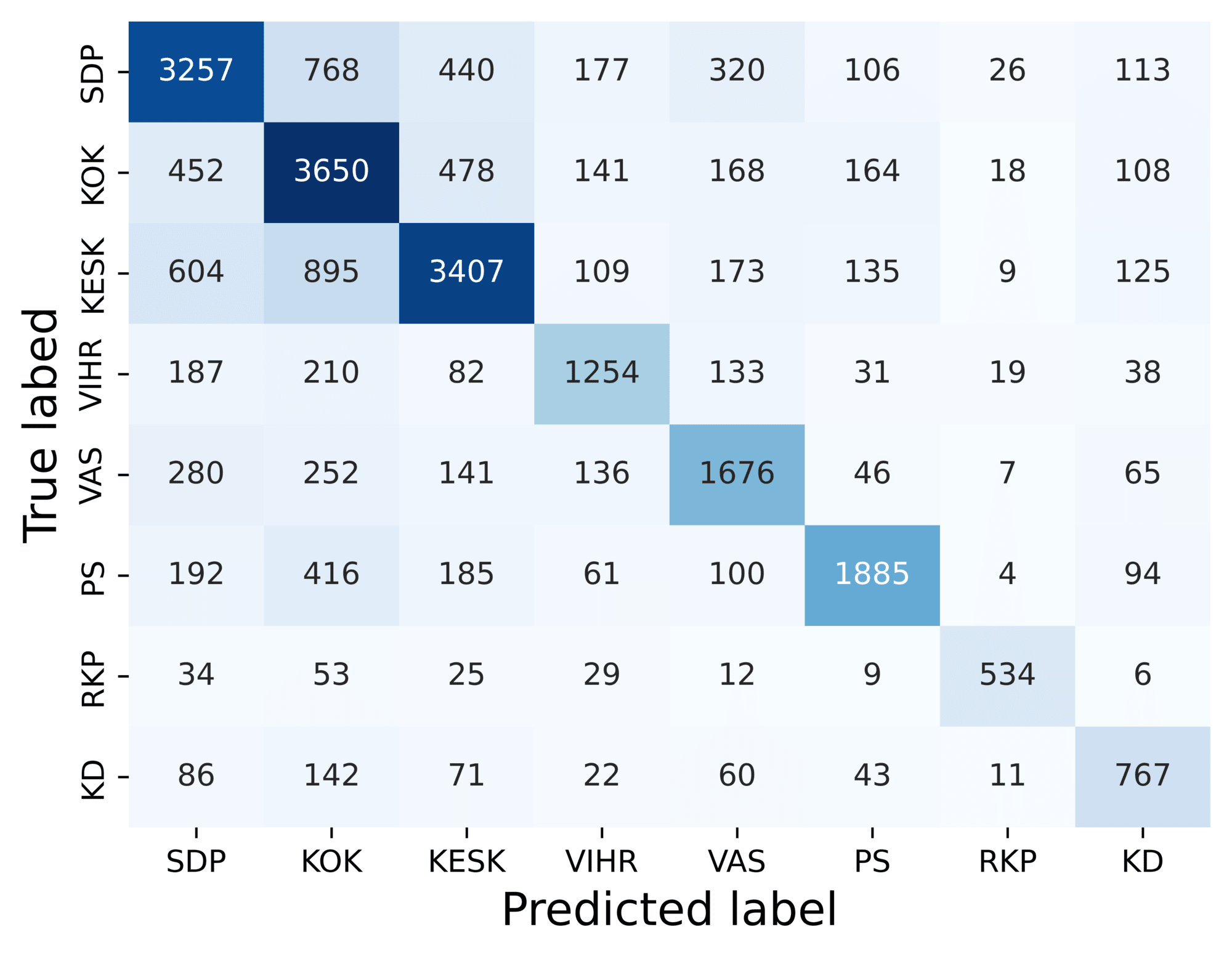

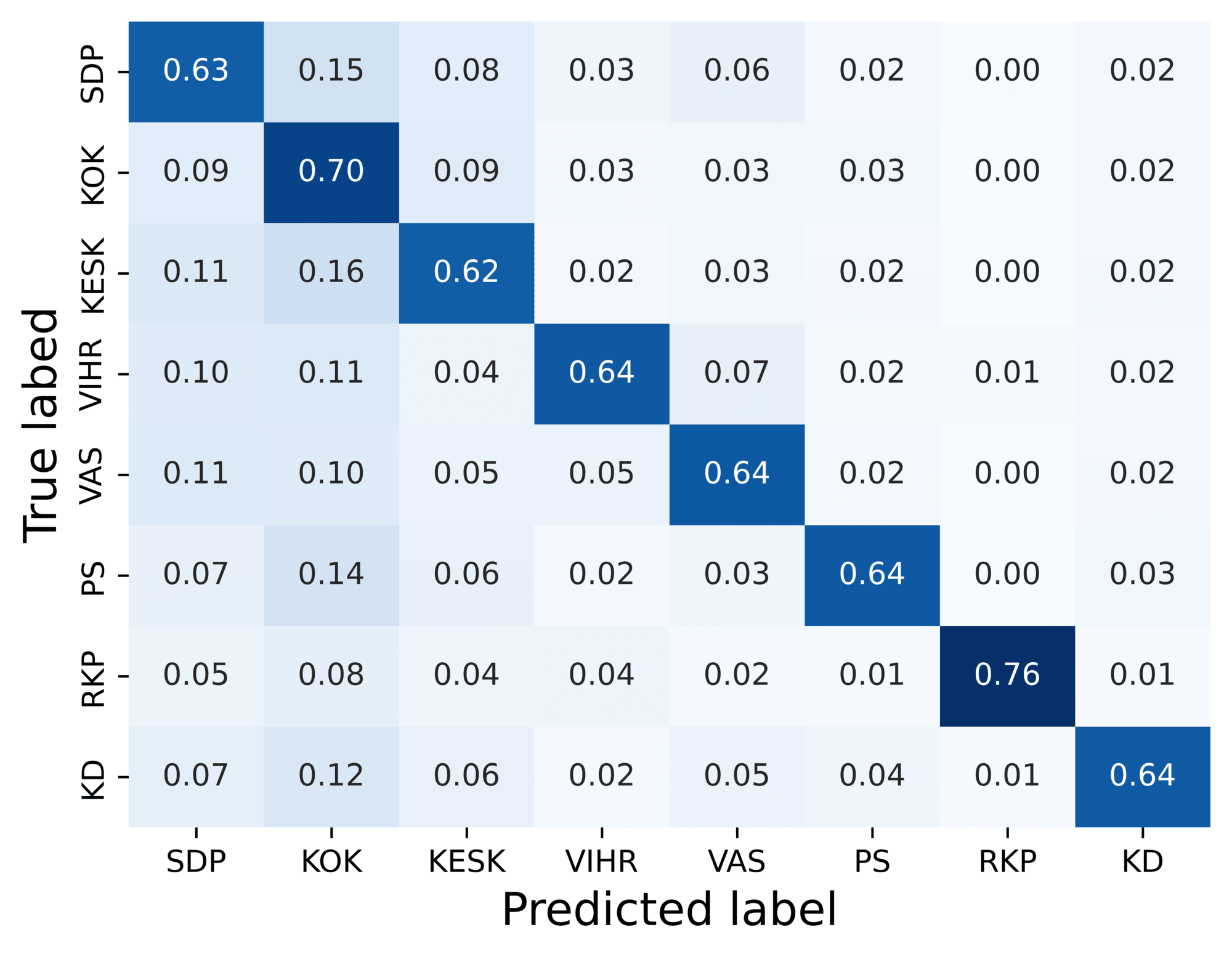

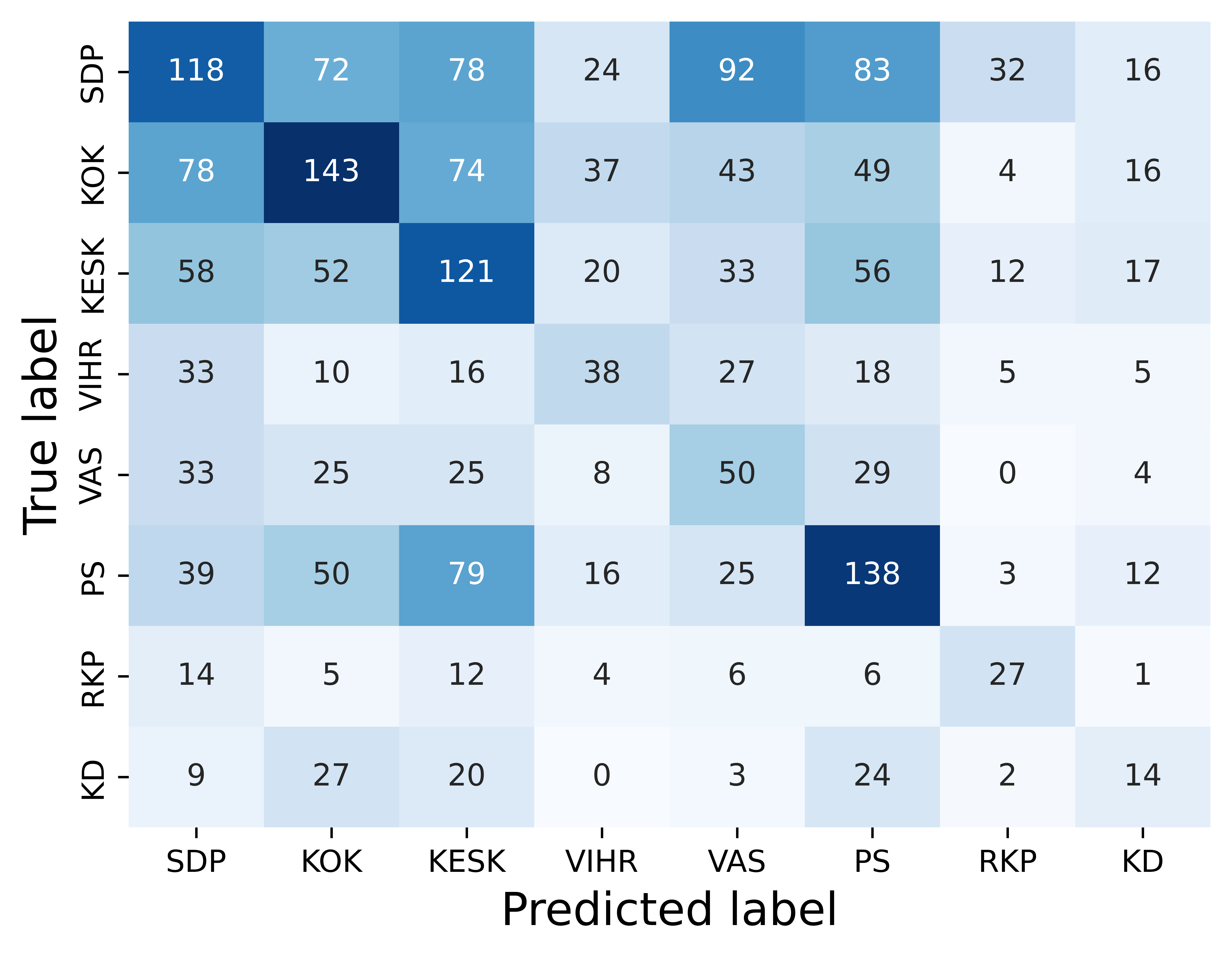

The confusion matrices in Figure 4 depict model performance. In the first confusion

matrix, we note that the model tends to confuse speeches from the three largest parties

(SDP, KOK, KESK) with each other. This suggests that there is something in common

between the speeches of these three parties. As the largest parties in parliament,

they often assume a leading role in government and opposition, which could explain

these similarities. The second confusion matrix shows that while National Coalition

(KOK) speeches are well recognised, it is also over-predicted, i.e., the model often

predicts that speeches from other parties are National Coalition speeches. In public

discourse, the party is often regarded as Finland’s ’economic party’ and our results

show that this reputation is not completely unearned. The strong connection between

the National Coalition and economic talk is evidenced by our finding that many speeches

that are mistakenly predicted to belong to the National Coalition concern public finances,

taxation or entrepreneurship.

Table 1 shows that the Swedish People’s Party (RKP) and the Finns (PS) have the highest

class-wise F1 scores, 0.79 and 0.70, respectively. The Swedish People Party’s speeches

are often partly or entirely in Swedish, which distinguishes them from other parties.

Although they are not the only party to use Swedish in parliamentSwedish is not used

exclusively by them, they are the party that uses the language the most, by far. The

Finns, on the other hand, are known for their populist rhetoric and colourful language

[

Ylä-Anttila and Ylä-Anttila 2015]. This sets them apart from other parties and could explain their higher F1 score.

This is also evidenced by the SHAP explanations, discussed below.

|

SDP |

KOK |

KESK |

VIHR |

VAS |

PS |

RKP |

KD |

| F1 |

0.63 |

0.61 |

0.65 |

0.64 |

0.63 |

0.70 |

0.79 |

0.62 |

Table 1.

Party-wise F1 scores, average of 5 training runs

The National Coalition is the label most often given to misclassified speeches, followed

by the Social Democrats and the Centre, i.e., the three largest parties. These results

are similar to those of Søyland and Lapponi (2017), who observed that larger parties

received more misclassification than smaller ones. It would be reasonable to assume

that parties that are close to each other ideologically, such as the Social Democrats

and the Left Alliance, also spokespeak similarly in parliament, and thus, would be

harder to distinguish from each other. YetHowever, the misclassifications only give

a weak signal that this is the case. Misclassified Left Alliance speeches are labelled

as Social Democrat speeches 30% of the time and National Coalition speeches 27% of

the time. Social Democrat speeches were most often misclassified as National Coalition

speeches (39%) and vice versa (30%). In fact, all theparty’s speeches of the parties,

except for the Left Alliance, are most often misclassified as National Coalition.

Overall, tThe Centre Party is overall the one most often misclassified. As they occupy

the political centre, they can at times take stances that are more aligned with the

political left and at other times align more with the political right, which could

explain why their speeches are most often misclassified.

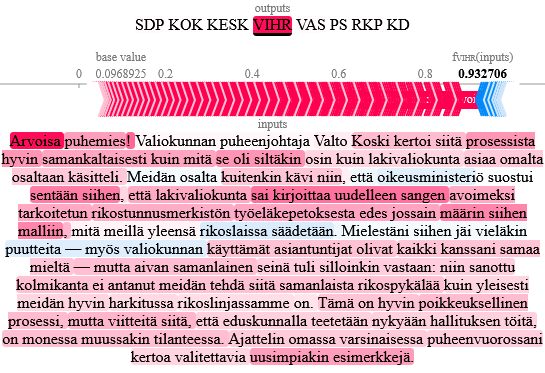

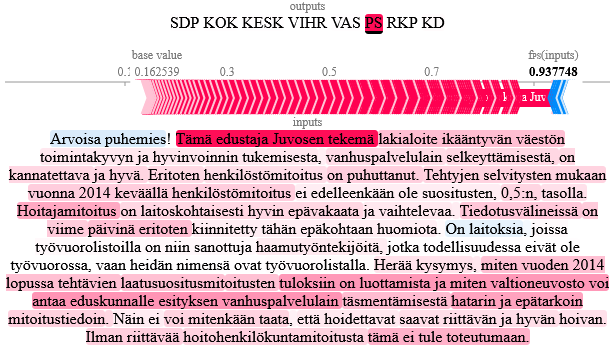

SHAP explanations

We analysed the SHAP explanations by taking a random sample of 20 correctly predicted

speeches with high prediction probability (>90%) from each party. As an example, Figure

5 shows a speech from the Green party. The words and phrases highlighted in red represent

features that were positive evidence (i.e. cue phrases) towards the model prediction and those in blue represent negative evidence, i.e.

the presence of these features make the prediction less likely. The darker the colour,

the stronger the effect that feature has on the prediction. In this example, the phrase

Arvoisa puhemies [Honoured chairman] was given a lot of weight by the model. We discuss possible explanations

for this at the end of this section.

Our analysis shows that the model paidys attention to two types of cue phrases, which

we call topical cues and rhetorical cues. Topical cues are phrases that relate to

a coherent topic, such as immigration, taxation, the EU. In other words, they convey

what the speech is about. Rhetorical cues on the other hand relate to style or tone

and are, at least in isolation, not directly linked to the topic of the speech. Rhetorical

cues are often identified by the presence of function words, adverbs and adjectives.

Table 2 aggregates some example SHAP cues that the model useds to identify the parties.

The SHAP cues show that the model has learned to identify both the core political

issues of the parties and also the style and tone of some individual speakers. The

SHAP explanations show that what makes the Social Democratic Party distinct is their

focus on the well-being of the unemployed and especially pensioners. They also provide

criticism of the free market and often use the term porvarihallitus [bourgeois government] to rebuke the actions of right-wing governments. The names

of National Coalition MPs are often strong explanatory features, which shows that

the Social Democrats position themselves as a counterforce to their free market policies.

The National Coalition is distinct in the way they talk critically about taxes and

government welfare programs. They highlight the importance of economic growth and

free markets. The fact that they occupied a government position for most of the two

decades that the data covers is also shown in the explanations, as phrases that applaud

the government can act as cue phrases. The Centre party speaks for the rural population:

their topical cue phrases concern different municipalities and areas, agriculture,

forestry and peat extraction, while the Christian Democrats stand out by raising issues

concerning healthcare and abortion. For the Finns, the model has learned to notice

their critical attitude towards the EU and incurring government debt. Another recurring

feature is critique against the government, which is likely a product of them occupying

the opposition position. Some rhetorical cues also highlight the party’s colloquial

style of the party and the populist rhetoric that they are known for. Examples of

these are koska koko kansa herää [when do the people wake up] and taitavat olla vanhimmatkin kansanedustajat hallitysryhmistä yhtä narrattavissa kuin

joulupukkiin uskovat lapset [even the oldest MPs in government seem to be as easily fooled as children who believe

in Santa Claus]. The Left Alliance has topical cue phrases that relate to defending

the poor and underprivileged, supporting welfare programs and workers’ rights. Additionally,

the party is also distinctive in its push for greener policies. The Swedish People’s

Party speeches were most easily identified by the use of the Swedish language. Cue

phrases that were not in Swedish concerned topics of equality and welfare as well

as the Finnish archipelago, which is where many Swedish speaking Finns live. Finally,

for the Green party, although topical cues relating to climate change and environmental

protection were present, the strongest cues were a result of the disproportionate

activity of MP Erkki Pulliainen, whose personal style has clearly had a strong impact

on what the model associates with the party. MP Pulliainen style of speaking in parliament

can be described as conversational or even playful and many adjectives and adverbs,

such as erikoisesti [peculiarly], täsmälleen [precicely], and äärimmäisen [utmost] often shine bright red in the SHAP explanations. Notably, out of the 20

Green party speeches sampled from the pool of correctly predicted speeches, 16 were

from MP Pulliainen.

| Party |

Examples of explanatory cues |

| Social Democratic Party |

"bourgeois government", "Zyskowicz", "the government is proposing great cuts into

pensioner housing benefits" |

| National Coalition |

"want to keep Finland a land of work and entrepreneurship", "encourage working and

diligence" |

| Centre |

"have defended the use of timber and Finnish peat", "to Savukoski" |

| Green party |

"so in other words", "carbon-neutral circular economy", "peculiarly" |

| Left Alliance |

"the poor and the underprivileged", "poverty has increased", "methane is a highly

potent greenhouse gas" |

| Finns |

"children who believe in Santa Claus", "more debt leads us on the Greek path" |

| Swedish People’s Party |

"Honoured chairman" (in Swedish), "equality legislation", "I would like to pay attention

to our marine conditions" |

| Christian Democrats |

"people’s health and illness", "abortion law", "risk of fetal disorder" |

Table 2.

Examples of party cues as indicated by SHAP explanations

Most of the SHAP cues discussed above are easy to understand to anyone with a thorough

understanding of the Finnish political parties and their political leanings. However,

there are also some surprising findings that are not easily explainable by party politics.

For instance, the customary greeting of the chairman or parts of it that starts virtually

all speeches, is shown to be a cue phrase of each party at least once in our sample

of speeches. Such is the case in Figure 55, where the word Arvoisa [Honoured] is the strongest individual cue in the whole speech. Why this is the case,

when all parties use the same phrase constantly, is unclear. There are variants of

this initial greeting where the explanation does make more sense. For instance, the

Finns cue phrase Kunnioitettu puhemies [Esteemed chairman!] is, in fact, used more by the Finns than other parties. At times,

the gender of the chair is revealed, when the greeting is Arvoisa (herra/rouva) puhemies [Honoured (Mr. /Mrs.) chairman!]. This gendered honorific is sometimes a cue phrase,

suggesting that the model has learned some temporal cues, as the chairman is at times

a woman and at others a man. Other puzzling explanatory phrases are rhetorical cues

that are mostly function words. As discussed above, sometimes they can be attributed

to the style and rhetoric of individual speakers that the model has learned to recognise.

At other times, the reason is much more obscure. Such is the example of sen tähden minusta tässä [because of that I think here], which is shown to be a strong cue phrase indicating

the Centre. This exact phrase appears only once in the training data and when it does,

it is spoken by a member of another party, namely the Christian Democrats. Yet, focusing

on only the beginning of this phrase, we realised that the Centre MP Timo Kalli usesd

the phrase sen tähden [because of that] 213 times in 141 speeches in the training data. In total this phrase

was usedappears 1190 times in 991 speeches in the training data, which means that

MP Kalli was responsible for roughlyaround 18% of all uses. Even though MP Kalli is

not a particularly active speaker, it seems that the model has noticed this particular

idiosyncrasy of one Centre MP and has thus come to associate it with the Centre party.

Lastly, the SHAP explanations show that even though mentions of party names were removed

and replaced with [PARTY], the model still learned to predict who is being referenced

based on the verb in the sentence. The Finns and the Christian Democrats are the only

parties, whose name is in plural form. Hence, when [PARTY] is the subject of the clause

and the verb is in plural form, the model knows that [PARTY] must be one of these

two parties.

In sum, our results show that the model has learned to identify the parties with decent

accuracy and that the Swedish People’s Party and the Finns are the most distinctive.

When the model misclassifies speeches, it most often gives the label of one of the

three largest parties. The model has learned to recognise the political leanings of

the parties but also uses rhetorical cues to make its predictions.

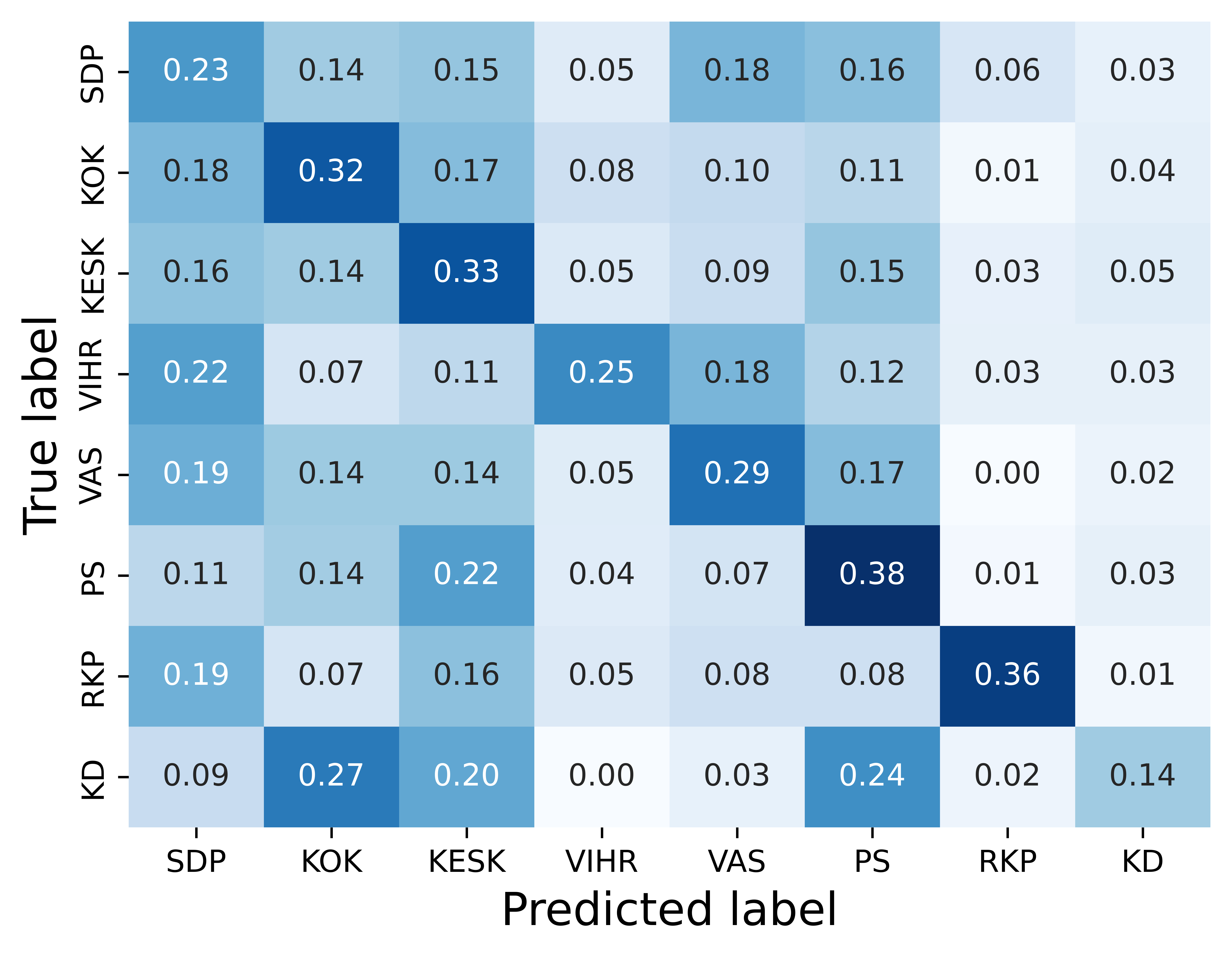

Questionnaire responses

A total of 438 people responded to the questionnaire. Each respondent labelled five

speeches resulting in a total of 2190 responses. Each speech was labelled between

15 and 28 times. Model accuracy on the 100 speech100-speech sample dataset was 62%,

whereas human accuracy was only 30%. In terms of F1 scores, the respondents correctly

identified speeches from the Finns most often, closely followed by the National Coalition

and the Swedish People’s Party, as shown in Table 3 and Figure 6. This result is similar

to model performance, reinforcing the notion that the Finns and the Swedish People’s

Party are distinctive. Conversely, responses were least often correct with Christian

Democrats’ speeches, where respondents reached an F1 score of just 0.15. Respondents

were asked to report their own estimate of their political knowledge but, surprisingly,

we found no correlation between reported political knowledge and accuracy in identifying

speeches. In terms of confidence, respondents gave an average score of 3.1 (1 = very

confident, 5 = not at all confident). We found that confidence correlates with accuracy.

The respondents found some speeches easier to connect to a party as evidenced by high

accuracy and high confidence score, while others were much harder.

Although the respondents did not perform too well in identifying party-specific political

speech, they performed far better when measured against their ability to identify

ideological similarities. If we use a simple left-right typology for the Finnish party

landscape, the success rate for identifying left-wing speakers wasis 50.3%, and for

right-wing speakers 71.5%. In this respect, our results indicate that respondent right-wing

speaking is somewhat easier to identify. However, more research with different political

texts and covering different contexts and periods of time is needed to obtain a clearer

picture about this.

|

SDP |

KOK |

KESK |

VIHR |

VAS |

PS |

RKP |

KD |

| F1 |

0.26 |

0.35 |

0.30 |

0.25 |

0.22 |

0.36 |

0.34 |

0.15 |

Table 3.

Party-wise F1 scores of human responses.

In addition to choosing a party, the respondents were asked to indicate which phrases

in the speech made them think that the speech was from the party that they believed.

Based on these responses, we formed a list of keywords. These were calculated by pooling

together all phrases that were chosen as cues for a given party. The phrases were

tokenized into words and lemmatized. We removed stop words and then calculated the

most frequent words for each party, which are shown in Table 4. It should be noted

that these keywords come from a set of only 100 speeches and should therefore not

be treated as representative of the party speeches as a whole. They do, however, give

some indication of what kinds of words people tend to associate with a given party.

The keywords indicate that people tend to be more topic focused than the model. The

topical keywords closely resemble those that the model has learned to identify: National

Coalition talk about economy, the Centre about regional matters and the Left Alliance

about unemployment.

| SDP |

KOK |

KESK |

VIHR |

VAS |

PS |

RKP |

KD |

| want |

must |

region |

human |

human |

Finland |

Swedish |

human |

| human |

Finland |

regional |

bring down |

government |

government |

then |

killing |

| good |

then |

country |

need |

must |

mind |

word |

life |

| government |

National Coalition |

then |

bear |

unemployed |

here |

own |

question |

| SDP |

economy |

good |

carcass |

cut |

important |

important |

child |

| then |

government |

MP |

set |

want |

then |

right |

ending |

| own |

time |

municipality |

sentence |

give |

must |

different |

government |

| must |

here |

government |

must |

time |

MP |

secure |

police |

| Finland |

police |

issue |

MP |

need |

very |

region |

Finland |

| employment |

country |

Finland |

Finland |

well |

issue |

very |

own |

| issue |

also |

strong |

issue |

small |

own |

go |

kill |

| need |

give |

well |

along |

cut |

talk |

honoured |

patient |

| propose |

work |

post |

juridical |

Finland |

police |

speaker |

important |

| time |

good |

must |

well |

issue |

current |

also |

hope |

| also |

growth |

whole |

sexual |

right |

want |

here |

yes |

| support |

get |

function |

orientation |

education |

yes |

issue |

good |

| well |

entrepreneur |

important |

question |

child |

year |

nordic |

must |

| National Coalition |

Europe |

different |

child |

most |

country |

honoured |

mind |

| say |

issue |

want |

whole |

work |

Europe |

good |

suicide clinic |

| important |

company |

wood |

right |

euro |

time |

court of appeal |

doctor |

Table 4.

Response keywords.

Comparison between model and humans

In comparisonWhen comparing the questionnaire response to model predictionsperformance,

Table 5 shows that the most common case is one in which the model made a correct prediction

while humans responded incorrectly. The next common case is one in which both were

incorrect. Only 9% of the time are humans correct while the model makes an incorrect

prediction. In this section, we analyse and compare the cue phrases chosen by the

questionnaire respondents to the cue phrases indicated by SHAP explanations. We do

this through a close reading of the speeches in the questionnaire and illustrate the

results with a selection of example speeches. The results show that while the model

useds both topical and rhetorical cues in its decision-making, the respondents reliedy

more heavily on topical cues. In the examples below, the phrases in bold are some

of the most important features for the model prediction as indicated by the SHAP explanations.

|

Model correct |

Model incorrect |

| Human correct |

458 / 21% |

191 / 9% |

| Human incorrect |

917 / 42% |

624 / 28% |

Table 5.

Human and model performance.

Different cues for model and humans

-

1. "Ja niin kuin edustaja Koskinen tässä jo totesi, niin mielestäni tänään täällä kuullut

puheenvuorot esimerkiksi pääministerin toimesta vain ikään kuin haastoivat meitä kaikkia siihen keskusteluun […] [M]eidän on laitettava suitsia näille

markkinavoimille, jotta me saamme palautettua näihin järjestelmiin sitä kansanvaltaa,

joka tänne kuuluu, näihin nimenomaisiin saleihin eri puolilla Eurooppaa."

"And as MP Koskinen already stated, in my opinion, what we have heard here today,

the speeches by for example the prime minister, as it were, challenged us to part-take in the discussion […] [W]e must start controlling these

market forces so we can reintroduce democracy to these systems, these exact halls all around Europe."

In Example 1, the speech from the Social Democrats was correctly predicted by the

model mostly based on the phrases in bold. The first phrase, a rhetorical cue, is

a rather mundane phrase that, intuitively, could be spoken by any MP from any party

and, indeed, was not indicated to be a cue phrase by any of the questionnaire respondents.

Yet, the model sees this as very informative. This could be due to the broader context,

such as the mention of MP Koskinen, which could be three different people, two of

whom are members of the SDP. The second phrase is more clearly linked to a coherent

topic, namely Europe and the EU, and in context, more specifically to controlling

market forces and strengthening democracy. It is curious, why this exact phrase at

the end of the speech is so important in the model’s decision making, when the phrases

before seem to be more informative, a claim supported by the respondents’ cue phrases.

12 of the 28 respondents who labelled this speech believed it was a Finns speech,

7 guessed SDP correctly, 4 picked the Left Alliance and rest of the answers were scattered

to other parties. Almost all respondents chose the phrase “mihin tämä koko unioni,

mihin euro on menossa” to be cue, regardless of the party they guessed. This indicates

that the respondents identified this phrase to be political but, at least here, devoid

of extra-linguistic context, could not connect it to a coherent political ideology

and party. In sum, this example illustrates how the model can base its predictions

on features that humans mostly ignore, and, in most cases, this makes it perform better.

Additionally, it shows an example of many respondents choosing the same cue but being

unable to accurately identify what it signifies.

-

2. "Tällä tavallahan tietenkään tilanne ei voi pidemmän päälle toimia, ja mielestäni

valiokunta toteaa aivan oikein, että 2013 — 2015 valtiontalouden kehyksiä tältä osin tarkastellaan uudelleen. [...] Nykyiset raja-asemien tilat sekä henkilöstö ovat käyneet

riittämättömiksi rajanylitysten kasvaessa kaksinumeroisilla luvuilla joka vuosi. [...]

Takanahan tässä asiassa on kaiken kaikkiaan se, että niin transito- kuin matkailuliikenne kasvaa todella kovaa vauhtia, ja kyllä sen matkailu- ja transitoliikenteen mukana myöskin meille tärkeää lisäarvoa eli rahaa tänne Suomenmaahan tulee."

"The situation cannot go on like this and, in my opinion, the Committee notes correctly

that the 2013–2015 state’s financial framework in this regard will be re-examined. [...] The current facilities and staff at border stations are

insufficient when border crossings increase by double-digit numbers each year. [...]

All in all, what is behind this is the fact that both transit and tourism traffic is growing really fast, and with this tourism and transit traffic, there is also an added value that is important to us, that is, money here in Finland."

In Example 2, another correctly predicted SDP speech, the first SHAP cue is partially

rhetorical and partially topical and the latter two are clearly topical. It is hard

to tell why the model focuseds on these phrases, when there are other, more politically

salient cues: most respondents believed this was a Finns speech due to the mention

of border crossings or a National Coalition speech because of the focus on economy.

Only one respondent chose "tourism and transit traffic" as part of their cue phrases,

which shows that this was not seen as salient cue even though it did help the model

make a correct prediction. Examples 1 and 2 illustrate how a machine learning model

can base its predictions on features that stray from human intuition.

Easily identified speeches

-

3. "Maamme on kotimaisten eurofiilien konsensuspoliitikkojen sekä Brysselin byrokraattien

toimesta jo melkein täysin alennettu EU:n merkityksettömäksi sivuprovinssiksi. Arvoisa herra puhemies! Suomalaisen kansanvallan edustajan on aina

asetettava Suomen ja suomalaisten etu ensimmäiseksi. Tämä vaatii joskus radikaaleja toimenpiteitä, mutta se, mikä on kansan etu, ei voi koskaan olla ylitsepääsemätöntä. […] Kansanäänestysteitse sveitsiläiset ovat

voineet painaa jarrua muun muassa vapaamielisten globalisaatiopoliitikkojen sekä heitä hännystelevän valtamedian massamaahanmuutto-

ja islamisointiprojekteille ilman, että tästä olisi syntynyt minkäänlaista Sveitsin eristämistä kansainvälisestä yhteisöstä.

[…] Lopuksi totean nopeasti, että kannatan tätä edustaja Hirvisaaren tekemää erinomaista lakialoitetta.

"Local Europhile consensus politicians and Brussels bureaucrats have almost completely

degraded our country into a meaningless EU side province. Honoured chairman! A representative of Finnish democracy must always

place Finland and the Finnish people first. Sometimes, this requires radical measures, but what is in the interest of the people can never be insurmountable. […] Through referenda, the Swiss have pulled the brakes

on, for example, the mass-immigration and Islamisation projects of liberal globalist politicians and

the mainstream media brown-nosing them, without Switzerland being shunned from the international community. […] Finally, I quickly

announce that I support this excellent bill proposed by MP Hirvisaari."

Six out of the 100 speeches were correctly identified by at least 80% of respondents.

One of these speeches was entirely in Swedish, which is what made it easy to connect

toassociate with the Swedish People’s Party. Four speeches directly mentioned the

name of the party in question. The sixth speech is shown in part in Example 3. This

speech comes from the Finns and is easily identified due to its anti-EU and anti-immigrant

sentiment as well as the compliments given to MP Hirvisaari, who was a relatively

well-known Finns MP. There is considerable overlap between the model’s and the respondents’

cues. Both the model and the respondents have identified the EU sceptic populist terminology,

such as “Brussels bureaucrats” and “globalist politicians”. This example shows that

the model explanations can be closely aligned with human intuition, especially when

the cues are as strong as they are here.

Model errors

-

4. "Tarkastakaa, miten oli euroalueella siihen aikaan, oliko siellä talouskasvua. Oli,

ja sen avulla Suomikin pääsi sitten talouskasvun imuun mukaan. Kysyisin pääministeriltä sitä, uskooko hän nyt, että tällainen vastaavantyyppinen elvytys,

mikä tehtiin silloin 2009, 2010 ja 2011, aikaansaisi talouskasvua, vai onko se kuitenkin

sitä, että meidän pitää täällä kotimarkkinoilla hoitaa kotipesämme kuntoon, ennen kuin päästään

kasvuun.”

"Please, check, what was the situation in the Euro zone, did the economy grow? It

did and Finland was also able to catch up with that economic growth. I would ask the prime minister, whether (s)he now believes that a similar stimulus, which was

carried out in 2009, 2010 and 2011, would lead to economic growth, or is it the case

that we need to get our house in order here in the domestic market before we get to

growth.”

Rarely, the respondents perform better than the model. The SHAP explanations reveal

that, in some cases, the model focusdes too much on rhetorical cues, while most respondents

could correctly recognise the clear topical cues. In Example 4, most respondents have

identified the economy related topical cues and, thus, correctly recognised that the

speech comes from the National Coalition. The SHAP explanation shows that model has

also noticed that these cues hint at the National Coalition, but the accusatory question

at the end of the speech misleads the model to predict Left Alliance. In Example 5,

a Centre speech, the model noticeds the repeated mentions of regional viability as

Centre cues but predicteds Social Democrats because of the topic of education. This

speech also split human responses along similar lines and similar reasons: 10 respondents

guessed Social Democrats or Left Alliance, but 13 went correctly with the Centre.

-

5. Yhteistyön myötä myös ammattikorkeakoulujen kannalta on hyödyllistä keskittyä tiettyihin

vahvoihin paikallisiin aloihin, jolloin korkeakoulu kykenee toimimaan vahvana alueellisena

vaikuttajana. [...] [A]mmattikorkeakoulut pystyvät tehokkaasti vastaamaan tulevaisuuden

haasteisiin ja [...] toimimaan vahvana alueellisena kehittäjänä.Through cooperation, universities of applied sciences benefit from focusing on specific,

local strengths, which enables the university to act as a strong regional player.

[...] [U]niversities of applied sciences can effectively meet the challenges of the

future and act as a strong regional advocate.

Speeches hard to identify

Some speeches were hard to identify correctly for both the model and the respondents.

Many of these speeches contain misleading topical cues, meaning that MPs discuss topics

that are strongly associated with a party other than their own. Such is the case in

Example 6, a speech from the Christian Democrats, which both the model and most respondents

thought was a National Coalition speech. The SHAP explanation and the cue phrases

chosen by the respondents both indicate that the talk about economic growth and markets

were misleading cues, as these are strongly associated with the National Coalition.

-

6. "Tarkastakaa, miten oli euroalueella siihen aikaan, oliko siellä talouskasvua. Oli,

ja sen avulla Suomikin pääsi sitten talouskasvun imuun mukaan. Kysyisin pääministeriltä sitä, uskooko hän nyt, että tällainen vastaavantyyppinen elvytys,

mikä tehtiin silloin 2009, 2010 ja 2011, aikaansaisi talouskasvua, vai onko se kuitenkin

sitä, että meidän pitää täällä kotimarkkinoilla hoitaa kotipesämme kuntoon, ennen kuin päästään

kasvuun.”

"Please, check, what the situation was in the Euro zone, did the economy grow? It

did and Finland was also able to catch up with that economic growth. I would ask the prime minister, whether (s)he now believes that a similar stimulus,

which was carried out in 2009, 2010 and 2011, would lead to economic growth, or is

it the case that we need to get our house in order here in the domestic market before we get to

growth.”

Conclusion

In this paper, we have trainedfine-tuned a BERT model to predict the party affiliation

of the speakers of parliamentary speeches in the Finnish parliament to assess the

distinctiveness of Finnish political parties and compared the model’s performance

to human responses to a similar task. We show that FinBERT outperforms SVM by an 8-point

difference in F1 score. This increase in performance comes at the cost of more computation

and less directly explainable results. However, Wwith the model explainability method

SHAP, we can ascertainsee which features the model has learned to associate with a

given party and how the model’s reasoning compares to human responses. In our analysis,

we identified two types of cue phrases: topical and rhetorical. Our results show the

model can distinguish between the parties not only by topical cues, but also by rhetorical

cues. This confirms previous observations that classification of political language

can be strongly affected by non-ideological linguistic features, such as opposition-government

positions ([

Hirst et al. 2010]) and stylistic features [

Potthast et al. 2018]. We also show that some parties, namely the Swedish People’s Party and the Finns

are more easily identified than the other parties.

The questionnaire responses indicate that the lack of clear topical cues strongly

diminishes a respondent’s ability to identify the parties. Interestingly enough, the

respondents seem to be well aware of this: the more uncertain a respondent is about

their assessment, the more probable it is that they have made a wrong guess. Human

respondents focus primarily on topic and sentiment, whereas the model can also find

meaningful information in other linguistic cues. This shows that citizens often cannot

make a reasonable assessment about an MPs party affiliation based on text alone and

that extra-linguistic context cues or other shortcuts are crucial for a citizen’s

understanding of politics and the ideological standings of political parties.

A machine learning model that is given the task to classify texts into distinct categories

will use any and all patterns it learns to identify from the training data to do so

with no regard to what a human might find intuitive. We have shown that many speeches

held in the Finnish parliament do, in fact, require such fine-grained understanding

of typical speech patterns and word choices to be labelled correctly, as they often

lack overt topical cues. Many speeches also contain misleading cues, i.e., phrases

conveying political positions that are strongly associated with a party other than

the speaker’s. These speeches were often mislabelled by respondents and by the model,

too, although the model was sometimes able to self-correct by looking for other cues

in the text. This shows that Finnish political parties discuss a multitude of topics

from a variety of viewpoints. The formation of new coalition governments every four

years forces the parties to adjust their politics, and thus, the things they say in

parliament, to suit their new environment.

Our results not only tell us about the distinctiveness of Finnish political parties

and the reasons behind it, but also, on a broader scale, show why model explainability

methods are a valuable tool for analysis in computational social sciences and digital

humanities. For example, machine learning in combination with model explanation methods

could be used to uncover latent political and ideological biases in seemingly neutral

text, such as news. As the use of machine learning becomes more prevalent in these

fields, it is important to consider the reasons a model behaves the way it does. It

is easy to assume a model bases its predictions on features that are intuitive to

a human analyst but as this study has shown, sometimes the model’s reasoning can be

counter intuitive. Depending on the learning task and research questions, this kind

of behaviour can be unwanted or even harmful if, for instance, it leads to reinforcing

racist or sexist stereotypes. Researchers who use machine learning methods in their

research should consider employing model explainability methods to support their analysis,

instead of just relying on accuracy metrics. Our analysis also shows how the SHAP

explanations, even though useful, are still limited: in many cases the model was shown

to base its predictions on features that are not intuitively obvious, but the explanation

does not tell why these features were important. In other words, we would ideally have an explanation

for the explanation. This is an area of research where much work is being done and

we will certainly see many advances in the near future.

Declarations

- This research was funded by the Research Council of Finland [grant number 353569].

- The corresponding author declares membership of the Left Alliance. The party had no

role in the funding or design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation

of data, the writing of the manuscript or any other aspect of the research.

- The authors wish to acknowledge CSC – IT Center for Science, Finland, for computational

resources.

Works Cited

Adams, Weschle, and Wlezien 2021 Adams, J., Weschle, S., and Wlezien, C. (2021)

“Elite interactions and voters’ perceptions of parties’ policy positions”,

American journal of political science, 65(1), 101–114. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12510.

Bayram, Pestian, Santel 2019 Bayram, U., Pestian, J., Santel, D., and Minai, A.A. (2019)

“What’s in a word? Detecting partisan affiliation from word use in congressional speeches”, in

2019 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN)). Budapest: IEEE. Available at:

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8851739/.

Berrar 2019 Berrar, D. (2019) “Cross-validation”, in S. Ranganathan, M. Gribskov, K. Nakai, and C. Schönbach (eds.) Encyclopedia of bioinformatics and computational biology. Academic Press.

Coverse 1975 Converse, P.E. (1975) “Public opinion and voting behavior”, in Greenstein, F.I. and Polsby, N. W. (eds.) Handbook of political science: Nongovernmental politics. Reading, MA.: Addison-Wesley, pp. 75–171.

Delli Carpini and Keeter 1993 Delli Carpini, M.X., and Keeter, S. (1993)

“Measuring political knowledge: Putting first things first”,

American Journal of Political Science, 37(4), pp. 1179–1206. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1086/269283.

Devlin et al. 2018 Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., and Toutanova, K. (2018)

“BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding”,

arXiv. (ArXiv preprint) Available at:

https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423/.

Devroe 2020 Devroe, R. (2020)

“Voters’ evaluation of (contra-)prototypical political candidates. An experimental

test of the interaction of candidate gender and policy positions cues in Flanders

(Belgium)”,

Electoral studies, 68. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102240.

Diermeier et al. 2011 Diermeier, D., Godbout, J.-F., Yu, B., and Kaufmann, S. (2011)

“Language and ideology in congress”,

British Journal of Political Science, 42(1), pp. 31–55. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123411000160.

Downs 1957 Downs, A. (1957) An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

Edelman 1988 Edelman, M. (1988) Constructing the political spectacle. The University of Chicago Press.

Elo and Rapeli 2010 Elo, K. and Rapeli, L. (2010)

“Determinants of political knowledge: The effects of the media on knowledge and information”,

Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 20(1), pp. 133–146. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1080/17457280903450799.

Gallagher et al. 2006 Gallagher, M., Laver, M., and Mair, P. (2006) Representative government in modern Europe (fourth edition). McGraw-Hill.

Genova and Greenberg 1979 Genova, B.K.L. and Greenberg, B.S. (1979)

“Interest in news and the knowledge gap”,

Public Opinion Quarterly, 43(1), pp. 79–91. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1086/26849325.

Hirst et al. 2010 Hirst, G., Riabinin, Y., and Graham, J. (2010)

“Party status as a confound in the automatic classification of political speech by

ideology”, in

10th

International Conference on Statistical Analysis of Textual Data (JADT 2010)). ROME: LED, pp. 731–742. Available at:

https://www.cs.toronto.edu/pub/gh/Hirst-etal-2010-JADT.pdf.

Hyvönen et al. 2021 Hyvönen, E. et al. (2021)

“Parlamenttisampo: eduskunnan aineistojen linkitetyn avoimen datan palvelu ja sen

käyttömahdollisuudet”,

Informaatiotutkimus, 40(3), pp. 216–244. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.23978/inf.107899.

Ilie 2018 Ilie, C. (2018) “Parliamentary debates”, in Ruth, W., and Bernhard, F. (eds.) The Routledge handbook of language and politics. Routledge.

Iyengar 1990 Iyengar, S. (1990) “Shortcuts to political knowledge”, in Ferejohn, J.A., and Kuklinski, J.H. (eds.) Information and Democratic Processes, University of Illinois Press.

Just 2022 Just, A. (2022)

“Partisanship, electoral autocracy, and citizen perceptions of party system polarization”,

Political behavior, 46, pp. 427–450. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09839-6.

Kapočiūtė-Dzikienė and Krupavičius 2014 Kapočiūtė-Dzikienė, J. and Krupavičius, A. (2014)

“Predicting party group from theLithuanian parliamentary speeches”,

Information Technology and Control, 43, pp. 321-332. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.itc.43.3.5871.

Lundberg and Lee 2017 Lundberg, S.M. and Lee, S.-I. (2017)

“A unified approach to interpreting model predictions”, in

31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017)). Red Hook, NY: Curran Associates Inc., pp. 4768–4777. Available at:

https://github.com/slundberg/shap.

Lupia 1994 Lupia, A. (1994)

“Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: Information and voting-behavior in California insurance

reform elections”,

American Political Science Review, 88(1), pp. 63–76. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.2307/294488226.

Navaretta and Hansen 2020 Navarretta, C. and Hansen, D.H. (2020)

“Identifying parties in manifestos and parliament speeches”, in

Proceedings of the Second ParlaCLARIN II Workshop. Marseille: European Language Resources Association, pp. 51–57. Available at:

https://aclanthology.org/2020.parlaclarin-1.10.

Navaretta and Hansen 2024 Navarretta, C. and Hansen, D.H. (2024)

“Government and ppposition in Danish parliamentary debates”, in

ParlaCLARIN IV Workshop on Creating, Analysing, and Increasing Accessibility of Parliamentary

Corpora. Torino: ELRA and ICCL, pp. 154–162. Available at:

https://aclanthology.org/2024.parlaclarin-1.23.pdf.

Németh 2023 Németh, R. (2023)

“A scoping review on the use of natural language processing in research on political

polarization: trends and research prospects”,

Journal of Computational Social Science, 6. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-022-00196-2.

Peterson and Spirling 2018 Peterson, A. and Spirling, A. (2018)

“Classification accuracy as a substantive quantity of interest: Measuring polarization

in Westminster systems”,

Political Analysis, 26(1), pp. 120–128. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2017.39.

Popkin and Dimock 1999 Popkin, S.L. and Dimock, M.A. (1999) “Political knowledge and citizen competence”, in Soltan, K.E. and Elkin, S.L. (eds.) Citizen competence and democratic institutions. University Park, PA.: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Potthast et al. 2018 Potthast, M. et al. (2018)

“A stylometric inquiry into hyperpartisan and fake news”, in

Proceedings of the 56th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics. Melbourne: Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 231–240. Available at:

https://aclanthology.org/P18-1022.

Rubinelli 2018 Rubinelli, S. (2018) “Rhetoric as a civic art from antiquity to the beginning of modernity”, in Ruth, W., and Bernhard, F. (eds.) The Routledge handbook of language and politics. Routledge.

Schuster and Nakajima 2012 Schuster, M. and Nakajima, K. (2012)

“Japanese and Korean voice search”, in

2012 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP)). Kyoto: IEEE, pp. 5149–5152. Available at:

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6289079/.

Subies et al. 2021 Subies, G.G., Sánchez, D.B., and Vaca, A. (2021)

“BERT and SHAP for humour analysis based on human annotation”, in

Iberian Languages Evaluation Forum (IberLEF 2021)). Malaga: CEUR-WS, pp. 821–828. Available at:

https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2943/haha_paper2.pdf.

Tilley and Wlezien 2008 Tilley, J., and Wlezien, C. (2008)

“Does political information matter? An experimental test relating to party positions

on Europe”,

Political Studies, 56(1), pp. 192–214. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00698.x.

Valentino et al. 2002 Valentino, N.A., Hutchings, V.L., and White, I.K. (2002)

“Cues that matter: How politicalads prime racial attitudes during campaigns”,